Wild horse

| Wild horse | |

|---|---|

| |

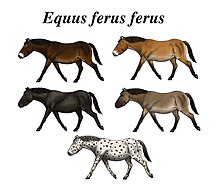

| Top left: Equus ferus caballus (horses) Top right: Equus ferus przewalskii (Przewalski's horse) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | E. ferus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Equus ferus Boddaert, 1785

| |

| Subspecies | |

The wild horse (Equus ferus) is a species of the genus Equus, which includes as subspecies the modern domesticated horse (Equus ferus caballus) as well as the undomesticated tarpan (Equus ferus ferus), now extinct, and the endangered Przewalski's horse (Equus ferus przewalskii).[2] Przewalski's horse was saved from the brink of extinction and reintroduced successfully to the wild. The tarpan became extinct in the 19th century, though it was a possible ancestor of the domestic horse, and roamed the steppes of Eurasia at the time of domestication.[3][4][5][6][7] However, other subspecies of Equus ferus may have existed and could have been the stock from which domesticated horses are descended.[8] Since the extinction of the tarpan, attempts have been made to reconstruct its phenotype, resulting in horse breeds such as the Konik and Heck horse. However, the genetic makeup and foundation bloodstock of those breeds is substantially derived from domesticated horses, so these breeds possess domesticated traits.

The term "wild horse" is also used colloquially to refer to free-roaming herds of feral horses such as the mustang in the United States, the brumby in Australia, and many others. These feral horses are untamed members of the domestic horse subspecies (Equus ferus caballus), and should not be confused with the two truly "wild" horse subspecies extant into modern times.

Subspecies and their history

E. ferus had several subspecies. Three survived into modern times:[9]

- The domestic horse (Equus ferus caballus).

- The tarpan or Eurasian wild horse (Equus ferus ferus), once native to Europe and western Asia, became effectively extinct in the late 19th century, and the last specimen died in captivity in an estate in Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire, in 1909.

- Przewalski's horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), also known as the Mongolian wild horse or Takhi, is native to Central Asia and the Gobi Desert.

The latter two are the only never-domesticated "wild" groups that survived into historic times.[8] However, other subspecies of Equus ferus may have existed and could have been the stock from which domesticated horses are descended.[8]

Przewalski's horse

Przewalski's horse occupied the eastern Eurasian Steppes, perhaps from the Urals to Mongolia, although the ancient border between tarpan and Przewalski distributions has not been clearly defined. Przewalski's horse was limited to Dzungaria and western Mongolia in the same period, and became extinct in the wild during the 1960s, but was reintroduced in the late 1980s to two preserves in Mongolia. Although researchers such as Marija Gimbutas theorized that the horses of the Chalcolithic period were Przewalski's, more recent genetic studies indicate that Przewalski's horse is not an ancestor to modern domesticated horses.[10][11]

Przewalski's horse is still found today, though it is an endangered species and for a time was considered extinct in the wild. Roughly 1500 Przewalski's horses are in zoos around the world. A small breeding population has been reintroduced in Mongolia.[12] As of 2005, a cooperative venture between the Zoological Society of London and Mongolian scientists has resulted in a free-ranging population of 248 animals in the wild.[13]

Przewalski's horse has some biological differences from the domestic horse; unlike domesticated horses and the tarpan, which both have 64 chromosomes, Przewalski's horse has 66 chromosomes due to a Robertsonian translocation. However, the offspring of Przewalski and domestic horses are fertile, possessing 65 chromosomes.[14]

Evolution and taxonomy

The horse family Equidae and the genus Equus evolved in North America, before the species moved into the Eastern Hemisphere. Studies using ancient DNA, as well as DNA of recent individuals, shows the presence of two closely related horse species in North America, the wild horse and Equus francisci, the "New World stilt-legged horse"; the latter is taxonomically assigned to various names.[6][16]

Currently, three subspecies that lived during recorded human history are recognized.[9] One subspecies is the widespread domestic horse (Equus ferus caballus),[9] as well as two wild subspecies, the recently extinct tarpan (E. f. ferus) and the endangered Przewalski's horse (E. f. przewalskii).[4][5][9]

Genetically, the pre-domestication horse, E. f. ferus, and the domesticated horse, E. f. caballus, form a single homogeneous group (clade) and are genetically indistinguishable from each other.[6][16][17][18] The genetic variation within this clade shows only a limited regional variation, with the notable exception of Przewalski's horse.[6][16][17][18] Przewalski's horse has several unique genetic differences that distinguish it from the other subspecies, including 66 instead of 64 chromosomes,[4][19] unique Y-chromosome gene haplotypes,[20] and unique mtDNA haplotypes.[21]

Besides genetic differences, osteological evidence from across the Eurasian wild horse range, based on cranial and metacarpal differences, indicates the presence of only two subspecies in postglacial times, the tarpan and Przewalski's horse.[8][22]

Scientific naming of the species

At present, the domesticated and wild horses are considered a single species, with the valid scientific name for the horse species being Equus ferus. The wild tarpan subspecies is E. f. ferus, Przewalski's horse is E. f. przewalskii, and the domesticated horse is E. f. caballus.[23] The rules for the scientific naming of animal species are determined in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, which stipulates that the oldest available valid scientific name is used to name the species. Previously, when taxonomists considered domesticated and wild horse two subspecies of the same species, the valid scientific name was Equus caballus Linnaeus 1758,[24] with the subspecies labeled E. c. caballus (domesticated horse), E. c. ferus Boddaert, 1785 (tarpan) and E. c. przewalskii Poliakov, 1881 (Przewalski's Horse). However, in 2003, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature decided that the scientific names of the wild species have priority over the scientific names of domesticated species, therefore mandating the use of Equus ferus for the horse, independent of the position of the domesticated horse.

Feral horses

Horses that live in an untamed state but have ancestors that have been domesticated are not truly "wild" horses; they are feral horses. For example, when the Spanish reintroduced the horse to the Americas beginning in the late 15th century, some horses escaped and formed feral herds, the best-known being the mustang. The Australian equivalent to the Mustang is the brumby, descended from horses strayed or let loose in Australia by English settlers.[25] Isolated populations of feral horses occur in a number of places, including Portugal, Scotland, and a number of barrier islands along the Atlantic coast of North America from Sable Island off Nova Scotia, to the Cumberland Island, Georgia.[26] While these are often referred to as "wild" horses, they are not truly "wild" in the biological sense of having no domesticated ancestors.

In 1995, British and French explorers discovered a new population of horses in the Riwoche Valley of Tibet, unknown to the rest of the world, but apparently used by the local Khamba people. It was speculated that the Riwoche horse might be a relict population of wild horses,[27] but testing did not reveal genetic differences with domesticated horses,[28] which is in line with news reports indicating that they are used as pack and riding animals by the local villagers.[29] These horses only stand 12 hands (48 inches, 122 cm) tall and are said to resemble the images known as "horse no 2" depicted in cave paintings alongside images of Przewalski's horse.[28]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Template:IUCN2011.2

- ^ Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 630–631. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "The First Horses: The Przewalskii and Tarpan Horses", The legacy of the horse, International Museum of the Horse, archived from the original on October 30, 2007, retrieved 2009-02-18

- ^ a b c Groves, Colin P. (1994). Boyd, Lee and Katherine A. Houpt (ed.). The Przewalski Horse: Morphology, Habitat and Taxonomy. Vol. Przewalski's Horse: The History and Biology of an Endangered Species. Albany, New YorkColin P. Groves: State University of New York Press.

- ^ a b Kavar, Tatjana; Peter Dovč (2008). "Domestication of the horse: Genetic relationships between domestic and wild horses". Livestock Science. 116: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2008.03.002.

- ^ a b c d Weinstock, J.; et al. (2005). "Evolution, systematics, and phylogeography of Pleistocene horses in the New World: a molecular perspective". PLoS Biology. 3 (8): e241. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030241. PMC 1159165. PMID 15974804. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bowling, Ann T.; Anatoly Ruvinsky (2000). "Genetic Aspects of Domestication, Breeds and Their Origin". In Ann T. Bowling; Anatoly Ruvinsky (eds.). The Genetics of the Horse. CABI Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85199-429-1.

- ^ a b c d Colin Groves, 1986, "The taxonomy, distribution, and adaptations of recent Equids," In Richard H. Meadow and Hans-Peter Uerpmann, eds., Equids in the Ancient World, volume I, pp. 11-65, Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

- ^ a b c d Don E. Wilson; DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. (2005). "Equus caballus". Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Wallner, B.; Brem, G.; Müller, M.; Achmann, R. (2003). "Fixed nucleotide differences on the Y chromosome indicate clear divergence between Equus przewalskii and Equus caballus". Animal Genetics. 34 (6): 453–456. doi:10.1046/j.0268-9146.2003.01044.x. PMID 14687077.

- ^ Lindgren, G.; Backström, N.; Swinburne, J.; Hellborg, L.; Einarsson, A.; Sandberg, K.; Cothran, G.; Vilà, C.; Binns, M.; Ellegren, H. (2004). "Limited number of patrilines in horse domestication". Nature Genetics. 36 (4): 335–336. doi:10.1038/ng1326. PMID 15034578.

- ^ "Przewalski's Horse". si.edu. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "An extraordinary return from the brink of extinction for worlds last wild horse" ZSL Living Conservation, December 19, 2005.

- ^ The American Museum of Natural History When Is a Wild Horse Actually a Feral Horse?

- ^ http://www.pnas.org/content/108/46/18626.full.pdf

- ^ a b c Orlando, L.; et al. (2008). "Ancient DNA Clarifies the Evolutionary History of American Late Pleistocene Equids". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 66 (5): 533–538. doi:10.1007/s00239-008-9100-x. PMID 18398561.

- ^ a b Cai, Dawei; Zhuowei Tang; Lu Han; Camilla F. Speller; Dongya Y. Yang; Xiaolin Ma; Jian'en Cao; Hong Zhu; Hui Zhou (2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the origin of the Chinese domestic horse". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (3): 835–842. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.11.006.

- ^ a b Vilà, Carles; Jennifer A. Leonard; Anders Götherström; Stefan Marklund; Kaj Sandberg; Kerstin Lidén; Robert K. Wayne; Hans Ellegren (2001). "Widespread Origins of Domestic Horse Lineages". Science. 291 (5503): 474–477. doi:10.1126/science.291.5503.474. PMID 11161199.

- ^ Benirschke, Poliakoff K.; N. Malouf; R. J. Low; H. Heck (16 April 1965). "Chromosome Complement: Differences between Equus caballus and Equus przewalskii". Science. 148 (3668): 382–383. doi:10.1126/science.148.3668.382. PMID 14261533.

- ^ Lau, Allison; Lei Peng; Hiroki Goto; Leona Chemnick; Oliver A. Ryder; Kateryna D. Makova (2009). "Horse Domestication and Conservation Genetics of Przewalski's Horse Inferred from Sex Chromosomal and Autosomal Sequences". Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 (1): 199–208. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn239. PMID 18931383.

- ^ Jansen, Thomas; Peter Forster; Marsha A. Levine; Hardy Oelke; Matthew Hurles; Colin Renfrew; Jürgen Weber; Klaus Olek (August 6, 2002). "Mitochondrial DNA and the origins of the domestic horse". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (16): 10905–10910. doi:10.1073/pnas.152330099. PMC 125071. PMID 12130666. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Eisenmann, Vera (1998). "Quaternary Horses: possible candidates to domestication". The Horse: its domestication, diffusion and role in past communities. Proceedings of the XIII International Congress of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences, Forli, Italia, 8–14 September 1996. Vol. 1. ABACO Edizioni. pp. 27–36.

- ^ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (2003). "Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are pre-dated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved. Opinion 2027 (Case 3010)". Bull. Zool. Nomencl. 60 (1): 81–84.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 73. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ^ Nimmo, D. G.; Miller, K. K. (2007). "Ecological and human dimensions of management of feral horses in Australia: A review". Wildlife Research. 34: 408–417. doi:10.1071/WR06102.

- ^ "Wildlife". Cumberland Island. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ^ Dohner, Janet Vorwald (2001). "Equines: Natural History". In Dohner, Janet Vorwald (ed.). Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Topeka, KS: Yale University Press. pp. 400–401. ISBN 978-0-300-08880-9.

- ^ a b Peissel, Michel (2002). Tibet: the secret continent. Macmillan. p. 36. ISBN 9780312309534.

- ^ Humi, Peter (17 November 1995). "Tibetan discovery is 'horse of a different color'". CNN. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

Bibliography

- Equid Specialist Group 1996. Equus ferus. In: IUCN 2006. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 22 May 2006 from http://www.iucnredlist.org/search/details.php?species=41763.

- Moelman, P.D. 2002. Equids. Zebras, Assess and Horses. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- Template:BibISBN/0801857899