William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan | |

|---|---|

| |

| 41st United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 5, 1913 – June 9, 1915 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Philander C. Knox |

| Succeeded by | Robert Lansing |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Nebraska's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1891 – March 3, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | William James Connell |

| Succeeded by | Jesse Burr Strode |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 19, 1860 Salem, Illinois, U.S.[1] |

| Died | July 26, 1925 (aged 65) Dayton, Tennessee |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Baird Bryan

(m. 1884–1925) |

| Children | Ruth Baird Bryan Owen (1885–1954) William Jennings Bryan, Jr. (1889–1978)[2] Grace Dexter Bryan (1891–1945)[3] |

| Alma mater | Illinois College Union College of Law |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American orator and politician from Nebraska, and a dominant force in the populist wing of the Democratic Party, standing three times as the Party's nominee for President of the United States (1896, 1900, and 1908). He served two terms as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Nebraska and was United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson (1913–1915). He resigned because of his pacifist position on World War I. Bryan was a devout Presbyterian, a strong advocate of popular democracy, and an enemy of the banks and the gold standard. He demanded "Free Silver" because he believed it undermined the evil "Money Power" and put more cash in the hands of the common people. He was a peace advocate, a supporter of Prohibition, and an opponent of Darwinism on religious and humanitarian grounds. With his deep, commanding voice and wide travels, he was perhaps the best-known orator and lecturer of the era. Because of his faith in the wisdom of the common people, he was called "The Great Commoner."

In the intensely fought 1896 and 1900 elections, he was defeated by William McKinley but retained control of the Democratic Party. With over 500 speeches in 1896, Bryan invented the national stumping tour in an era when other presidential candidates stayed home. In his three presidential bids, he promoted Free Silver in 1896, anti-imperialism in 1900, and trust-busting in 1908, calling on Democrats to fight the trusts (big corporations) and big banks, and embrace anti-elitist ideals of republicanism. President Wilson appointed him Secretary of State in 1913. After the Lusitania was torpedoed in 1915, Wilson made strong demands on Germany that Bryan disagreed with, resigning in protest as a pacifist. After 1920 he supported Prohibition and attacked Darwinism and evolution, most famously at the Scopes Trial in 1925 in Tennessee. Five days after the conclusion of the Scopes case, Bryan died in his sleep.[4]

Background and early career: 1860–1896

William Jennings Bryan was born in Salem, Illinois on March 19, 1860, to Silas Lillard Bryan and Mariah Elizabeth (Jennings) Bryan.[1] Bryan's mother was of English heritage. Mary Bryan joined the Salem Baptists in 1872, so Bryan attended Methodist services on Sunday morning with his father, and in the afternoon, Baptist services with his mother. At this point, William began spending his Sunday afternoons at the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. At age 14, Bryan attended a revival, was baptized, and joined the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In later life, Bryan said the day of his baptism was the most important day in his life, but at the time it caused little change in his daily routine. He later left the Cumberland Presbyterian Church and joined the larger Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

His father, Silas Bryan, of Scots-Irish and English ancestry,[5] was an avid Jacksonian Democrat. Silas won election to the Illinois State Senate, but was defeated for re-election in 1860. He won election as a state circuit judge, and in 1866 moved his family to a 520-acre (210.4 ha) farm north of Salem,[6] living in a ten-room house that was the envy of Marion County.[7]

Until age ten, Bryan was home-schooled, as many children were. The Bible and McGuffey Readers shaped his views that gambling and liquor were evil and sinful. To attend Whipple Academy, which was attached to Illinois College, Bryan was sent to Jacksonville, Illinois in 1874.

Following high school, he entered Illinois College, graduating as valedictorian in 1881. During his time at Illinois College, Bryan was a member of the Sigma Pi literary society. He studied law at Union Law College in Chicago (which later became Northwestern University School of Law). While preparing for the bar exam, he taught high school and met Mary Elizabeth Baird,[8] a cousin of William Sherman Jennings; the latter was also his own first-cousin. Bryan and Mary Elizabeth Baird married on October 1, 1884,[9] and they settled in Jacksonville, which at the time had a population of two thousand.

Mary also became a lawyer, and collaborated with Bryan on all his speeches and writings. He practiced law in Jacksonville from 1883 to 1887, then moved to the boom city of Lincoln, Nebraska. In Lincoln, he was raised a Master Mason in Lincoln Lodge 19, A.F. & A.M.[10] Bryan also met James Dahlman in Lincoln, and they became lifelong friends. As chairman of the Nebraska Democratic Party, Dahlman would help carry Nebraska for Bryan in two presidential campaigns. Even when Dahlman became closely associated with Omaha's vice elements, including the breweries, as the city's eight-term mayor, he and Bryan maintained a collegial relationship.[11]

In the Democratic landslide of 1890, Bryan was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Nebraska's First Congressional District. The growing prohibitionist movement had entered the election of 1890 with its own slate of candidates. In the three-way race in the First Congressional District, Bryan received 6,713 more votes than his nearest opponent. This was a plurality of the vote and was 8,000 votes short of a majority. Bryan was elected, only the second Democrat to be elected to Congress in the history of Nebraska.[12] In 1892, Bryan was re-elected by a 140-vote majority in a two-person race. He ran for the Senate in 1894, but a Republican landslide led to the Nebraska state legislature's choice of a Republican for the Senate seat (at that time, state legislatures elected their representatives to the US Senate).

First campaign for the White House: 1896

Bryan had an innate talent in oratory. He gave speeches, organized meetings, and adopted resounding resolutions that eventually culminated in the founding of the American Bimetallic League, which then evolved into the National Bimetallic Union, and finally the National Silver Committee.[13] At the time many farmers' groups believed that by increasing the amount of currency in circulation, commodities would receive higher prices. They were opposed by banks and bond holders who feared the effects of inflation. The ultimate goal of the league was to garner support on a national level for the reinstatement of the coinage of silver.[14] With his support, Charles H. Jones of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch was put on the platform committee and Bryan's "sixteen-to-one" plank for free silver was adopted and silently added to the platform for the 1896 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, in order to avoid controversy.[15] As a minority member of the resolutions committee, Bryan was able to push the Democratic Party from its laissez-faire and small-government roots toward its modern, liberal character. Through these measures, the public and influential Democrats became convinced of his capacity to lead and bring change, resulting in his being mentioned as a possible chairman for the Chicago convention.[16]

In 1893, the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act had resulted in the collapse of the silver market. Bryan delivered speeches across the country for free silver from 1894 to 1896, building a grass-roots reputation as a powerful champion of the cause.

At the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Bryan lambasted Eastern moneyed classes for supporting the gold standard at the expense of the average worker. His "Cross of Gold" speech, delivered on July 9, 1896,[17] instantly made him the sensational new face in the Democratic Party. That same year he became the first presidential candidate to campaign in a car (a donated Mueller) in Decatur, Illinois.[18]

The Bourbon Democrats who supported incumbent Democratic President Grover Cleveland were defeated, and the party's agrarian and silver factions voted for Bryan, giving him the nomination of the Democratic Party. At the age of 36, Bryan became (and still remains) the youngest presidential nominee of a major party in American history.

Disappointed with the direction of their party, Gold Democrats invited Cleveland to run as a third-party candidate, but he declined. Cleveland did, however, support John M. Palmer, nominee of the Gold Democrats, rather than Bryan.[19]

Bryan also formally received the nominations of the Populist Party and the Silver Republican Party. With the three nominations, voters from any party could vote for Bryan without crossing party lines.[20] In 1896, the Populists rejected Bryan's Democratic running mate, Maine banker Arthur Sewall, and named as his running mate Georgia Populist Thomas E. Watson. People could vote for Bryan and Sewall (on the Democratic or Silver Republican lines), or for Bryan and Watson (on the People's Party line).

The Republicans nominated William McKinley on a platform calling for prosperity for everyone through industrial growth, high tariffs, and "sound money" (gold). Republicans ridiculed Bryan as a Populist. However, "Bryan's reform program was not based on the Populists--for example, the Populists Free Silver took Free Silver from Bryan's Democrats, not vice versa--but he used the same crusading rhetoric against railroads, banks, insurance companies and businesses that has often been mistaken for Populism. Bryan remained a staunch Democrat throughout his career."[21] The popular political economist and social reformer Henry George influenced Bryan's thinking[22] and campaigned on his behalf.[23]

Bryan demanded Bimetallism and "Free Silver" at a ratio of 16:1. Most leading Democratic newspapers rejected his candidacy. Despite this rejection by the newspapers, Bryan won the Democratic vote.

Republicans discovered in August that Bryan was solidly ahead in the South and West, but far behind in the Northeast. He appeared to be ahead in the Midwest, so the Republicans concentrated their efforts there. They said Bryan was a madman, a religious fanatic surrounded by anarchists, who would wreck the economy.[24] By late September, the Republicans felt they were ahead in the decisive Midwest and began emphasizing that McKinley would bring prosperity to all Americans. McKinley scored solid gains among the middle classes, factory and railroad workers, prosperous farmers, and the German Americans who rejected free silver. Bryan gave 500 speeches in 27 states. McKinley won by a margin of 271 to 176 in the electoral college, but the popular vote was much closer and in some key states, McKinley's margin of victory was narrow.

War and peace: 1898–1900

With the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898, Bryan was forced to consider his party's stance on foreign policy. On one hand, Bryan was critical of militarism. Yet Spain's suppression of Cuban and Filipino self-government movements went against his view of his country's “Global Mission.” He envisioned the United States spreading democracy to the rest of the world. With this idealism in mind, Bryan enthusiastically supported President McKinley's declaration of war against Spain.[25] According to historian William Leuchtenburg, "few political figures exceeded the enthusiasm of William Jennings Bryan for the Spanish war."[26]

Bryan argued that "universal peace cannot come until justice is enthroned throughout the world. Until the right has triumphed in every land and love reigns in every heart, government must, as a last resort, appeal to force".[27] He volunteered for duty and became colonel of a Nebraska militia regiment. He contracted typhoid fever in Florida and stayed there to recuperate, never seeing combat.

Bryan surprised many of his fellow party members by supporting the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, which resulted from the United States' defeat of Spain. The treaty granted the United States control of Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba, the Philippines, and parts of the West Indies. Many of Bryan's supporters were opposed to what they perceived as Republican aspirations of turning the country into an imperial power and criticized Bryan for hypocritically supporting the ratification of the treaty. Bryan justified supporting the treaty by arguing that the issue of imperialism should be decided upon by the American people at the ballot boxes and not in Congress. However, when the Bacon Resolution (a proposed supplement to the Treaty of Paris which would allow the Filipinos a “stable and independent government") failed to pass, Bryan began publicly speaking out against the Republicans' imperial aspirations.[28]

Bryan gave a speech at the Democratic National Convention in 1900 simply titled "Imperialism." In this speech he discusses his views against the annexation of the Philippines, questioning the United States' right to overpower people of another country just to gain a military base. He mentions, at the beginning of the speech, that the United States should not try to emulate the imperialism of Great Britain and other European countries, who were in this period extending their power in Asia and Africa.

Presidential election of 1900

In 1900 Bryan ran as an anti-imperialist, finding himself in alliance with industrialist Andrew Carnegie, as well as others who had fought against silver. Republicans mocked Bryan as indecisive, or a coward.

Bryan combined anti-imperialism with free silver, saying:

"The nation is of age and it can do what it pleases; it can spurn the traditions of the past; it can repudiate the principles upon which the nation rests; it can employ force instead of reason; it can substitute might for right; it can conquer weaker people; it can exploit their lands, appropriate their property and kill their people; but it cannot repeal the moral law or escape the punishment decreed for the violation of human rights."[29]

In a typical day he gave four hour-long speeches and shorter talks that added up to six hours of speaking. At an average rate of 175 words a minute, he turned out 63,000 words a day, enough to fill 52 columns of a newspaper. In Wisconsin, he once made 12 speeches in 15 hours.[30]

Despite Bryan's tremendous energy, McKinley and the Republicans were too strong to defeat. The GOP invested ten times as much money into the campaign as did Bryan's Democratic Party. While Bryan declared “Imperialism to be the paramount issue,” he had difficulty differentiating his platform from that of the Republican party. While he argued for the US to take on the role of a protectorate to the Philippines, the Republicans argued that annexation of the Philippines would eventually lead to independence. With the issue of imperialism being defined in these vaguely similar terms, the Republicans' “full pale” platform of a strong American industrial economy proved to be more important to voters than questions of the morality of annexing the Philippines.[31] Bryan held his base in the South, a one-party Democratic region where virtually only white men voted, since the effective disenfranchisement of most blacks at the turn of the century, but lost part of the West; McKinley retained the populous Northeast and Midwest and rolled up a comfortable margin of victory. McKinley won the electoral college with a count of 292 votes compared to Bryan's 155. Bryan's hold on his party was weakened, while his erstwhile allies the Populists had virtually disappeared from the arena.

Presidential election of 1908

The 1908 election was Bryan’s third attempt to gain the presidency. The Democrats nominated Bryan by a wide margin at the Democratic convention held in Denver and decided on John Kern, a politician from Indiana, as his running mate. Bryan ran against the Republicans and Theodore Roosevelt’s hand-picked nominee William Howard Taft.

Bryan launched a special message to Congress, suggesting income and inheritance taxes, publicity on campaign contributions, and opposing the use of the navy for the collection of private debts.[32] He campaigned against corporate domination, urging that all corporation contributions be made public before election day, and that failure to cooperate be made a penal offense.[33]

The GOP ran its campaign on the benefits of the Roosevelt administration, creation of a postal service, continuation of "Sound Currency", citizenship for Puerto Rico inhabitants, regulation of big business, and tariff revision in protectionist mode.[34]

Bryan and the Democrats’ platform denounced the wrongs done by the Republican party: Congress spent too much money; Roosevelt hand picked Taft in undemocratic fashion; Republicans wanted centralization; Republicans favored monopolies. In response, Bryan publicized the slogan, "Shall the People Rule?" In a time of peace and prosperity, and Republican trust-busting, Bryan fared poorly among the voters. He lost the electoral college 321 to 162, his worst defeat yet, and did not carry any of the states in the Northeast.

In his three presidential election bids, Bryan received a total of 493 electoral votes - the most of any candidate in American history who never won the presidency.

Chautauqua circuit: 1900–1912

Following his defeat in the election of 1900, Bryan needed money, and his powerful voice and 100% name recognition were assets that could be capitalized. For the next 25 years, Bryan was the most popular speaker on the Chautauqua circuit, delivering thousands of paid speeches on current events in hundreds of towns and cities across the country, even while serving as Secretary of State. He usually charged $500 per speech in addition to a percentage of the profits. He mostly spoke about Christianity, but covered a wide variety of topics.[35] His most popular lecture (and his personal favorite) was "The Prince of Peace", which stressed that Christian theology was the solid foundation of morality, and individual and group morality was the foundation for peace and equality. Another famous lecture from this period, "The Value of an Ideal", was a stirring call to public service.

In a 1905 speech, Bryan warned that "the Darwinian theory represents man reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate, the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak. If this is the law of our development then, if there is any logic that can bind the human mind, we shall turn backward to the beast in proportion as we substitute the law of love. I choose to believe that love rather than hatred is the law of development."[citation needed]

Bryan threw himself into the work of the Social Gospel. He served in organizations with numerous theological liberals—he sat on the temperance committee of the Federal Council of Churches, and on the general committee of the short-lived Inter-church World Movement.

In 1901 Bryan founded a weekly magazine, The Commoner,[36] calling on Democrats to dissolve the trusts, regulate the railroads more tightly, and support the Progressive Movement.[37] Bryan was not a stranger to editorial practices having worked at the Omaha World Herald from 1894 to 1896 this early work provided himself a foundation in publishing. From 1901 to 1923 Bryan would publish and edit The Commoner curating, at its peak, a circulation of nearly 275,000 copies annually across the United states.[36] The paper revealed Bryan's evolving thoughts on political discourse. He regarded prohibition as a "local" issue and did not endorse a constitutional amendment until 1910. In London in 1906, he presented a plan to the Inter-Parliamentary Peace Conference for arbitration of disputes that he hoped would avert warfare. He tentatively called for nationalization of the railroads, then backtracked and called only for more regulation. His party nominated Bourbon Democrat Alton B. Parker in 1904, who lost to Roosevelt. For two years following this defeat, Bryan would pursue his public speaking ventures on an international stage. From 1904 to 1906, Bryan traveled globally, preaching, sightseeing with his wife Mary, lecturing, and all while escaping the political upheaval in Washington. Bryan crusaded as well for legislation to support introduction of the initiative and referendum as a means of giving voters a direct voice, making a whistle-stop campaign tour of Arkansas in 1910.[38] Bryan's speech to the students of Washington and Lee University began the Washington and Lee Mock Convention.

Bryan owned land in Nebraska and a 240-acre (0.97 km2) ranch in Texas; he paid for both with his strong earnings from speeches and The Commoner.[39]

Secretary of State: 1913–1915

For supporting Woodrow Wilson for the presidency in 1912, Bryan was appointed Secretary of State, the top cabinet position. For all his enormous influence in the Democratic Party, his two years as Secretary of State was the only time he served in a powerful office. Historian Richard Hofstadter comments:

- Bryan in power was like Bryan out of power: he made the same well-meant gestures, showed the same willingness under stress or confusion to drop ideas he had once been committed to, the same inability to see things through.[40]

Wilson took his measure and only nominally consulted him, making all the major foreign policy decisions from the White House. In the civil war in Mexico in 1914, Bryan supported American military intervention.

On July 13, 1913 Bryan gave the main speech at the opening of the Grove Park Inn in Asheville NC. Fred Seely, inn manager and son-in-law of Edwin Wiley Grove, sponsored Bryan and other dignitaries.

Bryan kept busy in 1913-1915, negotiating 28 treaties that promised arbitration of disputes before war broke out between the signatory countries and the United States. He made several attempts to negotiate a treaty with Germany, but ultimately could not succeed. The agreements, known officially as "Treaties for the Advancement of Peace," set up procedures for conciliation rather than for arbitration.[41] In September 1914 Bryan wrote President Wilson urging mediation in the World War that had just begun in Europe, with the U.S. as the largest neutral:

It is not likely that either side will win so complete a victory as to be able to dictate terms, and if either side does win such a victory it will probably mean preparation for another war. It would seem better to look for a more rational basis for peace.[42]

Bryan tried to yoke the American credit to the Entente, saying "money is the worst of all contrabands because it commands everything else," but eventually yielded. He also pointed out that by traveling on British vessels, which were at risk of attack, "an American citizen can, by putting his own business above his regard for this country, assume for his own advantage unnecessary risks and thus involve his country in international complications" [43] Wilson's demands from Germany for "strict accountability for any infringement of [American] rights, intentional or incidental" after the sinking of the Lusitania troubled Bryan, who counseled an “evenhanded policy.”[44] Bryan resigned in June 1915, protesting “… why be so shocked by the drowning of a few people, if there is to be no objection to starving a nation.”[45]

Despite their differences, Bryan campaigned as a private citizen for Wilson's reelection in 1916. When war was declared in April 1917, Bryan wrote Wilson, "Believing it to be the duty of the citizen to bear his part of the burden of war and his share of the peril, I hereby tender my services to the Government. Please enroll me as a private whenever I am needed and assign me to any work that I can do."[46] Wilson, however, did not allow the 57-year-old Bryan to rejoin the military, and did not offer him any wartime role.

Prohibition battles and Florida Real Estate: 1916–1925

Bryan campaigned for the Constitutional amendments on prohibition and women's suffrage. Partly to avoid Nebraska ethnics such as the German Americans who were "wet" and opposed to prohibition,[47] Bryan moved to Coconut Grove in Miami, Florida in 1913. He called his home on Brickell Avenue Villa Serena. Later, in 1925, he moved to a new home further south in Coconut Grove on Main Highway called Marymont.[48][49] Bryan filled lucrative speaking engagements, including playing the part of spokesman for George E. Merrick's new planned community Coral Gables, addressing large crowds across a Venetian pool, for an annual salary of over $100,000.[50] He was also extremely active in Christian organizations. Bryan refused to support the 1920 Democratic presidential nominee, James M. Cox, because he deemed Cox not dry enough. As one biographer explains,

Bryan epitomized the prohibitionist viewpoint: Protestant and nativist, hostile to the corporation and the evils of urban civilization, devoted to personal regeneration and the social gospel, he sincerely believed that prohibition would contribute to the physical health and moral improvement of the individual, stimulate civic progress, and end the notorious abuses connected with the liquor traffic. Hence he became interested when its devotees in Nebraska viewed direct legislation as a means of obtaining anti-saloon laws.[51]

Bryan's national campaigning helped Congress pass the 18th Amendment in 1918, which shut down all saloons as of 1920. But while prohibition was in effect, Bryan did not work to secure better enforcement. He opposed a highly controversial resolution at the 1924 Democratic National Convention condemning the Ku Klux Klan, expecting the organization would soon fold. Bryan disliked the Klan but never publicly attacked it.[52] For the nomination in 1924, he opposed the wet Al Smith; Bryan's younger brother, Nebraska Governor Charles W. Bryan, was put on the ticket with John W. Davis as candidate for vice president to keep the Bryanites in line. Bryan was very close to his brother and endorsed him for the vice presidency.

Bryan was the chief proponent of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, the precursor to the modern War on Drugs. However, he argued for the act's passage more as an international obligation than on moral grounds.[53]

After his resignation as Secretary of State, until his death, Bryan became an active promoter of Florida real estate, and lived in the Miami area during the colder months. His promotions (in print, speeches and even radio talks) probably contributed to the Florida real estate boom of the 1920s. "The Great Commoner" Bryan became rich from his real estate investments and promotion fees. The Florida boom collapsed within months after Bryan's death in 1925.

Anti-evolution activism: 1918–1925

Before World War I, Bryan believed moral progress could achieve equality at home and, in the international field, peace among all the world's nations.[54][55]

Bryan opposed the Darwinian theory of evolution for two reasons. First, he believed that what he considered a materialistic account of the descent of man (and all life) through evolution was directly contrary to the Biblical creation account, which he accepted. Second, he considered Darwinism as applied to society (Social Darwinism) to be a great evil force in the world, promoting hatred and conflicts, especially the World War, and inhibiting upward social and economic mobility of the poor and oppressed.[56]

In his famous Chautauqua lecture, "The Prince of Peace" (1909), Bryan warned that the theory of evolution could undermine the foundations of morality. He concluded, "while I do not accept the Darwinian theory I shall not quarrel with you about it." Evoking the design argument, he said, "I have a right to assume, and I prefer to assume, a Designer back of the design— a Creator back of the creation."[57]

One book Bryan read at this time convinced him that Darwinism emphasizing the struggle of races had undermined morality in Germany.[58] Bryan was deeply influenced by Vernon Kellogg's 1917 book, Headquarters Nights: A Record of Conversations and Experiences at the Headquarters of the German Army in Belgium and France, which asserted (on the basis of a conversation with a reserve officer he called "Professor von Flussen") that German intellectuals were totally committed to might-makes-right due to "whole-hearted acceptance of the worst of Social Darwinism, the Allmacht of natural selection applied to human life and society and Kultur."[59]

Bryan also read The Science of Power (1918) by British social theorist Benjamin Kidd, which credited the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche with German nationalism, materialism, and militarism. He described this as the working out of the social Darwinian hypothesis.[60]

In 1920, Bryan told the World Brotherhood Congress that the theory of evolution was "the most paralyzing influence with which civilization has had to deal in the last century" and that Nietzsche, in carrying the theory of evolution to its logical conclusion, "promulgated a philosophy that condemned democracy,... denounced Christianity,... denied the existence of God, overturned all concepts of morality,... and endeavored to substitute the worship of the superhuman for the worship of Jehovah."[61]

By 1921, Bryan considered Darwinism as a major internal threat to the US. He was affected by James H. Leuba's major study, The Belief in God and Immortality, a Psychological, Anthropological and Statistical Study (1916). In this study, Leuba shows that during four years of college a considerable number of college students lost their faith. Bryan was horrified that the next generation of American leaders might have the degraded sense of morality which he believed had prevailed in Germany and caused the Great War. Bryan launched an anti-evolution campaign.[62]

The campaign kicked off in October 1921, when the Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia invited Bryan to deliver the James Sprunt Lectures. In his lecture entitled "The Origin of Man", Bryan asked, "what is the role of man in the universe and what is the purpose of man?" For Bryan, the Bible was absolutely central to answering this question, and moral responsibility and the spirit of brotherhood could rest only on belief in God.

The Sprunt lectures were published as In His Image, and sold over 100,000 copies, while "The Origin of Man" was published separately as The Menace of the theory of evolution and also sold very well.[63]

Bryan was worried that the theory of evolution was making grounds not only in the universities, but also within the church. Many colleges were still church-affiliated. The developments of 19th century liberal theology, and higher criticism in particular, had allowed many clergymen to be willing to embrace the theory of evolution and claim that it was not contradictory with their being Christians. Determined to put an end to this, Bryan, who had long served as a Presbyterian elder, decided to run for the position of Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, which was at the time embroiled in the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy. (Under Presbyterian church governance, clergy and laymen are equally represented in the General Assembly, and the post of Moderator is open to any member of the General Assembly.) Bryan's main competition in the race was the Rev. Charles F. Wishart, president of the College of Wooster in Ohio, who had loudly endorsed the teaching of the theory of evolution in the college. Bryan lost to Wishart by a vote of 451-427. Bryan failed in gaining approval for a proposal to cut off funds to schools where the theory of evolution was taught. Instead, the General Assembly announced disapproval of materialistic (as opposed to theistic) evolution.

In his efforts to publicize his cause, Bryan joined the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1924 and attended the annual meeting.[64] A featured session at the meeting was a debate on biological evolution between Bryan and Edward Loranus Rice, a developmental biologist from the Methodist-associated Ohio Wesleyan University.

According to historian Ronald L. Numbers, Bryan was not nearly as much a fundamentalist as many modern-day creationists of the 21st century. Instead he is more accurately described as a "day-age creationist". Numbers says Bryan, "not only read the Mosaic "days" as geological "ages" but allowed for the possibility of organic evolution—so long as it did not impinge on the supernatural origin of Adam and Eve."[65]

Scopes trial: 1925

Bryan actively lobbied for state laws banning public schools from teaching evolution. The legislatures of several Southern states proved more receptive to his anti-evolution message than the Presbyterian Church had been, and passed such laws after Bryan addressed them. A prominent example was the Butler Act of 1925, which made it unlawful in Tennessee to teach that mankind evolved from lower life forms.[66]

Bryan's participation in the highly publicized 1925 Scopes Trial served as a capstone to his career. He was asked by William Bell Riley to represent the World Christian Fundamentals Association as counsel at the trial. During the trial, Bryan took the stand and was questioned by defense lawyer Clarence Darrow about his views on the Bible. "Asked when the Flood occurred, Bryan consulted Ussher's Bible Concordance, and gave the date as 2348 B.C., or 4273 years ago. Did not Bryan know, asked Darrow, that Chinese civilization had been traced back at least 7000 years?" Bryan conceded that he did not. When he was asked if the records of any other religion made mention of a flood at the time he cited, Bryan replied: "The Christian religion has always been good enough for me - I never found it necessary to study any competing religion."[67]

The national media reported the trial in great detail, with H. L. Mencken ridiculing Bryan as a symbol of Southern ignorance (despite his not being from the South) and anti-intellectualism. In a more humorous vein, satirist Richard Armour stated in It All Started With Columbus that Darrow had "made a monkey out of" Bryan due to Bryan's ignorance of the Bible.

After the judge retroactively expunged all of Bryan's answers to Darrow's questions, both sides closed without summation. The jury quickly returned a guilty verdict with the defense's encouragement, and Bryan won the case. However, the state Supreme Court reversed the verdict on a technicality.

Bryan linked Darwinism to what he considered to be the might-makes-right philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. Bryan believed that such thinking served not so much as an explanation for injustice but more as an excuse for injustice, particularly in the areas of harming the weak and waging war. In contrast, Bryan was influenced by the social philosophy of Leo Tolstoy, Christian humanitarian and pacifist.[68]

Death

In the days following the Scopes trial Bryan traveled hundreds of miles, delivering speeches in multiple towns. On Sunday, July 26, 1925, he returned from Chattanooga, Tennessee to his home in Dayton. After attending church services he ate a large meal, then died during a nap that afternoon, five days after the trial's conclusion. When someone remarked to Darrow that Bryan died from a "broken heart", Darrow responded, "Broken heart, hell, he died of a busted belly!"[69] Journalist H. L. Mencken, who disliked Bryan intensely,[70] reportedly boasted to Darrow that "we killed the son of a bitch".[71]

Bryan is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His headstone reads, "Statesman. Yet Friend To Truth! Of Soul Sincere. In Action Faithful. And In Honor Clear". He was survived by his daughter, Congresswoman Ruth Bryan Owen, and her four children: John Bryan Leavitt and Ruth Leavitt, by her first husband, Newport, Rhode Island artist William Homer Leavitt; and two children by her second husband, British Royal Engineers officer Reginald A. Owen.[72]

Ruth's eldest son John Bryan Leavitt, who had been adopted by his grandfather after his parents' divorce, became a poet and an actor, working professionally as John Bryan.[73]

Bryan College, a Christian-oriented institution, opened in 1930 in Dayton as a lasting memorial to Bryan.

Popular image

L. Frank Baum satirized Bryan as the Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900. Baum had been a Republican activist in 1896 and wrote on McKinley's behalf.[74][75][76][77]

Inherit the Wind, a 1955 play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, is a highly fictionalized account of the Scopes Trial written in response to McCarthyism. A populist thrice-defeated Presidential candidate from Nebraska named Matthew Harrison Brady comes to a small town named Hillsboro in Tennessee to help prosecute a young teacher for teaching evolution to his schoolchildren. He is opposed by a famous trial lawyer, Henry Drummond (based on Darrow), and mocked by a cynical newspaperman (based on H.L. Mencken) as the trial assumes a national profile. A 1960 Hollywood film adaptation, written by the playwrights, was directed by Stanley Kramer and stars Spencer Tracy as lawyer Henry Drummond and Fredric March as his friend and rival Matthew Harrison Brady.

Bryan also appears as a character in Douglas Moore's 1956 opera The Ballad of Baby Doe and is briefly mentioned in John Steinbeck's East of Eden. In addition, he is a (very) minor character in Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel. His death is referred to in Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises. In Robert A. Heinlein's Job: A Comedy of Justice, Bryan's unsuccessful or successful runs for the presidency are seen as the "splitting off" events of the alternate histories through which the protagonists travel.

He also has a biographical part in "The 42nd Parallel" in John Dos Passos' USA Trilogy.[78]

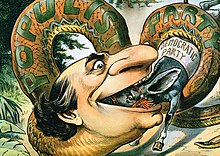

In political cartoons

The sheer volume of political propaganda cartoons featuring Bryan is a testament to the amusement and fear he caused among conservatives.[citation needed] Bryan campaigned tirelessly, championing the ideas of the farmers and workers, using his skills as a famed orator to ultimately reshape the Democratic Party into a more progressive one. These political cartoons attacked just about every facet of Bryan’s character and policy. They mocked his religious fervor, his campaign slogans, and even his ability to unify parties for a common cause. As Keen puts it, "The art of propaganda is to create a portrait that incarnates the idea of what we wish to destroy so we will react rather than think, and automatically focus our free-floating hostility, indistinct frustrations, and unnamed fears".[79] Bryan embodied these fears of the Republican Party of the time, which is clearly evident in the lengths they went to deface his character in these cartoons.

The most notable cartoons are of Bryan illustrated as a snake, representing Populism, swallowing a donkey, symbolizing the Democratic Party. Another notable Bryan cartoon is one where he is standing atop a Bible, marketing the sales of a "crown of thorns" and a "cross of gold" both referencing "The Cross of Gold," his most popular speech.

Nicknames

Bryan had an unusually high number of nicknames given to him in his lifetime; most of these were given by his loyal admirers in the Democratic Party. In addition to his best-known nickname, "The Great Commoner", he was also called "The Silver Knight of the West" (due to his support of the free silver issue) and the "Boy Orator of the Platte" (a reference to his oratorical skills and his home near the Platte River in Nebraska). A derisive nickname given by journalist H.L. Mencken, a prominent Bryan critic, was "The Fundamentalist Pope", a reference to Bryan's devout religious views. He is called "Adam-and-Eve" Bryan in "O Russet Witch!, Tales of the Jazz Age" by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Legacy

Michael Kazin considers Bryan the first of the 20th century "celebrity politicians", better known for their personalities and communications skills than their political views. Bryan was never comfortable with the black community, and attacked Roosevelt in 1904 for inviting Booker T. Washington to the White House to further the social equality between the races; he supported disfranchisement of southern blacks.[80] Form and content mix uneasily in Bryan's politics. The content of his speeches leads in a direct line to the progressive reforms adopted by 20th century Democrats. But the form his actions took was a romantic invocation of the American past, a populist insistence on the wisdom of ordinary folk, and a faith-based insistence on sincerity and character.[81]

In his book They Also Ran, Irving Stone criticizes Bryan as an egocentric who never admitted being wrong. Stone argues that because Bryan led a privileged life, he could not feel the suffering of the common man. He asserts that Bryan only acted as a champion of common men in order to get their votes. Stone claims that none of Bryan's ideas were original, and that he did not have the brains to be an effective president. He calls Bryan one of the nation's worst Secretaries of State. He believes that, as President, Bryan would have supported many blue laws. In Stone's opinion, Bryan had one of the least disciplined minds of the 19th century, and McKinley, Roosevelt and Taft all made better Presidents than Bryan would have been. His biographer Paolo Coletta reports that Bryan relied solely on his own judgments, and did not try to consult experts. He was suspicious not only of the plutocracy but of the intelligentsia, ridiculing them as the "aristocracy of learning" and "the scientific soviet."[82]

Many prominent Democrats have praised Bryan and his legacy. In 1962, former President Harry Truman said Bryan "was a great one—one of the greatest." Truman also claimed: "If it wasn't for old Bill Bryan, there wouldn't be any liberalism at all in the country now. Bryan kept liberalism alive, he kept it going."[83] In 1900, Truman, aged 16, was a page at the Democratic National Convention in Kansas City. He heard Bryan speak and was deeply impressed. In 1900 Truman and his father "declared themselves thorough 'Bryan men'... Bryan remained an idol for Harry, as the voice of the common man."[84] Tom L. Johnson, the progressive mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, referred to Bryan's campaign in 1896 as "the first great struggle of the masses in our country against the privileged classes." In a 1934 speech dedicating a memorial to Bryan, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said "I think that we would choose the word 'sincerity' as fitting him [Bryan] most of all...it was that sincerity that served him so well in his life-long fight against sham and privilege and wrong. It was that sincerity which made him a force for good in his own generation and kept alive many of the ancient faiths on which we are building today. We...can well agree that he fought the good fight; that he finished the course; and that he kept the faith."[85]

Bryan was one of the best known orators of his time. He was a fixture in the Democratic Party, and a hero to the common man. Starting with his Cross of Gold speech, Bryan brought the Populists into the Democratic Party, and with his common man message he would inevitably draw the African-American and feminist vote into the party. A strong believer in the power of government to improve people’s lives, Bryan expressed his belief to John Reed in 1916 that the government “may properly impose a minimum wage, regulate hours of labor, pass usury laws, and enforce inspection of food, sanitation and housing conditions.”[86] Bryan became the bridge that brought different factions into the party, and paved the way for liberal Democrats such as Franklin D. Roosevelt with his New Deal legislation. As noted by Bryan's biographer Michael Kazin:

- Bryan was the first leader of a major party to argue for permanently expanding the power of the federal government to serve the welfare of ordinary Americans from the working and middle classes....he did more than any other man--between the fall of Grover Cleveland and the election of Woodrow Wilson--to transform his party from a bulwark of laissez-faire to the citadel of liberalism we identify with Franklin D. Roosevelt and his ideological descendants.[87]

Kazin, however, also emphasizes the limits of Bryan's influence in the progressive mindset:

- His one great flaw was to support, with a studied lack of reflection, the abusive system of Jim Crow – a view that was shared, until the late 1930s, by nearly every white Democrat....After Bryan's death in 1925, most intellectuals and activists on the broad left rejected the amalgam that had inspired him: a strict populist morality based on a close read reading of Scripture....Liberals and radicals from the age of FDR to the present have tended to scorn that credo as naïve and bigoted, a remnant of an era of white Protestant supremacy that has, or should have, passed.[88]

Bryan is also remembered for his prophetic statement shortly after he became the Secretary of State in 1913: “I believe there will be no war while I am Secretary of State, and I believe there will be no war as long as I live.”[89]

Leo Tolstoy admired Bryan to such an extent the Russian kept no other image on his bedroom wall than Bryan's.[90]

Honors

Bryan County, Oklahoma is named after him.[91] Bryan Medical Center (formerly BryanLGH Medical Center and Bryan Memorial Hospital) in Lincoln, Nebraska, Bryan College of Health Science, connected with the hospital in Lincoln, and Bryan College, located in Dayton, Tennessee, are also named for William Jennings Bryan. The William Jennings Bryan House in Nebraska was named a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1963. A $4,000 scholarship for Creighton University students participating in Speech and Debate at the university is named after William Jennings Bryan. The Bryan Home Museum is a by-appointment only museum at his birthplace in Salem, Illinois. Salem is also home to Bryan Park and a large statue of Bryan. Omaha Bryan High School and Bryan Middle School in Bellevue, Nebraska are named for him. He is also honored by having an elementary school in Mission, Texas named after him, Bryan Elementary School on a street named after him, Bryan Street. His home at Asheville, North Carolina from 1917 to 1920, the William Jennings Bryan House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.[92]

A statue of Bryan represents the state of Nebraska at the National Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol. Bryan was named to the Nebraska Hall of Fame in 1971. A bust of him was dedicated as part of the Hall of Fame in 1974 which currently resides, like other members of the hall of fame, in the Nebraska State Capitol.[93]

He has been honored by the United States Postal Service with a $2 Great Americans series postage stamp.

The actor Ainslie Pryor played Bryan in a 1956 episode of the CBS anthology series, You Are There which focuses on the Cross of Gold speech.[94]

In 2013, Bryan was inducted into the Gennett Records Walk of Fame to commemorate his recording of the Cross of Gold speech.

See also

- History of creationism

- Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy

- Progressive Movement

- Henry Clay (another notable person who also unsuccessfully ran for president multiple times)

Notes

- ^ a b William Jennings Bryan Nebraska State Historical Society

- ^ "William Jennings Bryan, Jr". Find A Grave. Find A Grave, Inc. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ "Grace Dexter Bryan Hargreaves". Find A Grave. Find A Grave, Inc. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ Jeffrey P. Moran, The Scopes Trial: A Brief History with Documents (2002)

- ^ Asked when his family "dropped the 'O'" from his O'Bryan surname, he replied there never had been one. Bryan Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan; Kessinger p. 22-26. Likewise there never was a "T" at the end of the name.

- ^ Paolo E. Colletta, William Jennings Bryan: Colletta: Volume 1, Political Evangelist, 1860-1908 (University of Nebraska: Lincoln, 1964) pp. 3-4.

- ^ Paulo E. Colleta, William Jennings Bryan: Volume 1, Political Evangelist, 1860-1908, p. 5.

- ^ Paulo E. Colletta, William Jennings Bryan: Volume I, Political Evangelist, 1860-1908, p. 21.

- ^ Paulo E. Colletta, William Jennings Bryan: Volume I, Political Evangelist, 1860-1908, p. 30.

- ^ Parsons, John T. (2007). 150 Famous Masons. Richmond, Virginia: Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply. ISBN 978-0-88053-198-6.

- ^ B.W. Folsom, No More Free Markets Or Free Beer: The Progressive Era in Nebraska, 1900–1924 (1999), pp. 57-59.

- ^ Paulo E. Colletta, William Jennings Bryan: Volume I, Political Evangelist, 1860-1908., p. 48.

- ^ Paulo E. Colletta, William Jennings Bryan: Volume I, Political Evangelist, 1860-1908, p. 107.

- ^ Paxton Hibben, The Peerless Leader, William Jennings Bryan (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, incorporated, 1929), 175.

- ^ Paxton Hibben, The Peerless Leader, William Jennings Bryan (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, incorporated, 1929),184.

- ^ Paxton Hibben, The Peerless Leader, William Jennings Bryan (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, incorporated, 1929),177.

- ^ "Bryan's "Cross of Gold" Speech: Mesmerizing the Masses". historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ Lewis, Mary Beth. "Ten Best First Facts", in Car and Driver, 1/88, p.92.

- ^ William DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents, Gramercy 1997

- ^ The Populists and Silver Republicans were virtually defunct in 1900, and he did not again run on any third-party tickets.

- ^ Coletta, (1964), vol.1, pg.40

- ^ White, Lawrence (2012). The clash of economic ideas : the great policy debates and experiments of the last hundred years. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 110762133X.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert C. "Reform--By George!". New York Times. HarpWeek. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Glad (1964)

- ^ Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 86.

- ^ Woods, Thomas (2004-08-02) "The Progressive Peacenik Myth", The American Conservative

- ^ Sicius, Francis J. (2015). The Progressive Era: A Reference Guide, p. 182. Denver: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-447-6.

- ^ Kendrick A. Clements, William Jennings Bryan: Missionary Isolationist(Knoxville, The University of Tennessee Press, 1982), 34.

- ^ Hibben, Peerless Leader, 220

- ^ Coletta 1:272

- ^ Clements, William Jennings Bryan, 38.

- ^ Paxton Hibben, The Peerless Leader, William Jennings Bryan (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, incorporated, 1929), 266.

- ^ Hibben, The Peerless Leader, (1929), 279.

- ^ usaelectionatlas.org election 1908

- ^ Coletta, William Jennings Bryan vol 2 p. 2

- ^ a b See Katherine, Walter. "About The Commoner". Nebraska Newspapers. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved 12 October 2016. for all issues of the published paper.

- ^ See The Commoner Condensed Volume 3 (1901) for full text of annual compilation

- ^ Steven L. Piott, Giving Voters a Voice: The Origins of the Initiative and Referendum in America (2003) pp 126-32

- ^ The Commoner. Lincoln, Nebraska: William J. Bryan http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/46032385/. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Richard Hofstadter (2011) [1948]. The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made it. Knopf. pp. 257–58.

- ^ Genevieve Forbes Herrick; John Origen Herrick (2005) [1925]. The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Kessinger Publishing. p. 280.

- ^ Lawrence W. Levine (1965). Defender of the Faith: William Jennings Bryan, the Last Decade, 1915-1925. Harvard U.P. p. 8.

- ^ Lawrence W. Levine, Defender of the faith: William Jennings Bryan, the last decade, 1915–1925 (1987) p. 8

- ^ Healy, Gene. The Cult of the Presidency. America’s dangerous devotion to Executive Power. Washington, DC, Cato Institute, 2009, p. 65

- ^ Schmidt, Donald E. The Folly of War: American Foreign Policy 1898-2005. New York: Algora Publishing, 2005, p. 79

- ^ Hibben, Peerless Leader, p. 356

- ^ Coletta 3:116

- ^ City of Miami Historic Preservation Serena

- ^ City of Miami Historic Preservation Church

- ^ George, Paul S. "Brokers, Binders & Builders: Greater Miami's Boom of the Mid-1920s." Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 59, no. 4. 1981. pp. 440-463.

- ^ Coletta, William Jennings Bryan vol 2 p. 8

- ^ Coletta, William Jennings Bryan 3:162, 177, 184; Kazin

- ^ Historical documents

- ^ Merle Curti, Bryan and world peace (1931)

- ^ Paola Coletta, William Jennings Bryan's Plans for World Peace, Nebraska History (1977) 58#2 pp: 193–217

- ^ Coletta, William Jennings Bryan vol 3 ch 8

- ^ See The Prince of Peace

- ^ Coletta, William Jennings Bryan vol 3 p. 200

- ^ Bryan was especially influenced by pp 22-31 of Kellogg's book, which is online in snippet view and full text.

- ^ Bryan, Memoirs 552-53

- ^ Bradley J. Longfield, The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates (1991) p 68

- ^ Coletta 3:200

- ^ Bryan, In His Image (1922) full text online

- ^ Gilbert, J. (1997). "William Jennings Bryan, Scientist". University of Chicago Press In: Redeeming Culture:American Religion in An Age of Science. pp. 22–35. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ronald L. Numbers, The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design, (2006), p. 13

- ^ "It shall be unlawful..." to teach "...any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." Section 1 of House Bill No. 185

- ^ Paul Y. Anderson, "Sad Death of a Hero," American Mercury, v. 37, no. 147 (March 1936) 293-301.

- ^ George E. Webb (2002). The Evolution Controversy in America. University Press of Kentucky. p. 67.

- ^ Kazin, M. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Anchor Press (2007), p. 134. ISBN 0385720564.

- ^ Mencken, HL (1925): "In Memoriam: W. J. B.". The Phora archive. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ Kazin (2007), p. 138.

- ^ Bryan and Grandson Hunt, The New York Times, Nov. 23, 1913

- ^ Time. November 24, 1930 http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,740782,00.html?iid=chix-sphere.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ John G. Geer and Thomas R. Rochon, "William Jennings Bryan on the Yellow Brick Road," The Journal of American Culture Volume 16 Issue 4, (June 2004) Pages 59–63 doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1993.00059.x

- ^ Dighe, Ranjit S. (2002). The Historian's Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum's Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 31–32.

- ^ N. Gregory Mankiw (2012). Principles of Economics, 6th Ed. p. 663.

- ^ Rockoff, Hugh (1990). "The" Wizard of Oz" as a monetary allegory". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (4): 739–760. doi:10.1086/261704. JSTOR 2937766.

- ^ Dos Passos, John (1896-1970). U.S.A. Daniel Aaron & Townsend Ludington, eds. New York: Library of America, 1996.

- ^ Keen (1986), p, 26

- ^ Michael Kazin, A godly hero: The life of William Jennings Bryan (2006) p 93, 114.

- ^ Quotations of William Jennings Bryan

- ^ Paolo Coletta, "Will the Real Progressive Stand Up? William Jennings Bryan and Theodore Roosevelt to 1909," Nebraska history (1984) 65#1 pp 15-57 at p 25

- ^ Merle Miller, pp. 118-119

- ^ David McCullough, Truman p. 63

- ^ "Franklin D. Roosevelt: Address at a Memorial to William Jennings Bryan". ucsb.edu.

- ^ "Defender of the Faith". google.co.uk.

- ^ Michael Kazin (2007). A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Knopf Doubleday. p. xix.

- ^ Kazin (2007). A Godly Hero. p. xix.

- ^ Cited in Malcolm Wallop, "America Needs a Post-Containment Doctrine", Orbis, 37/2, (1993): p 191.

- ^ Kazin, Michael A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (2007) p. 170

- ^ Oklahoma Historical Society. "Origin of County Names in Oklahoma", Chronicles of Oklahoma 2:1 (March 1924) 75-82 (retrieved August 18, 2006).

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Nebraska Hall of Fame Members". nebraskahistory.org.

- ^ "Ainsile Pryor". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

References and sources

- Bryan, William Jennings. William Jennings Bryan: selections ed. by Ray Ginger (1967) 259 pages

- Bryan, William Jennings. The first battle: a story of the campaign of 1896 (1897), 693pp; campaign speeches online edition

- The Commoner Condensed, annual compilation of The Commoner magazine; full text online for 1901, 1902, 1903, 1907, 1907, 1908

- Bryan, William Jennings. The old world and its ways (1907) 560 pages full text online

- Bryan, William Jennings. Speeches of William Jennings Bryan edited by Mary Baird Bryan (1909) full text online

- Bryan, William Jennings. In His image (1922) 226pp full text online

- Bryan, William Jennings. The Memoirs: of William Jennings Bryan, by himself and his wife (1925) 560pp; online edition

- Bryan, William Jennings. British Rule in India (1906) Online Edition

Further reading

Biographies

- Cherny, Robert W. A Righteous Cause: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (1994).

- Coletta; Paolo E. William Jennings Bryan 3 vols. (1964), the most detailed biography. online vol 1; online vol 2; online vol 3

- Coletta, Paolo. "Will be Real Progressive Stand Up? William Jennings Bryan and Theodore Roosevelt to 1909," Nebraska history (1984) 65#1 pp 15–57

- Glad, Paul W. The Trumpet Soundeth: William Jennings Bryan and His Democracy 1896–1912 (1966).

- Hibben; Paxton. The Peerless Leader, William Jennings Bryan (1929).

- Kazin, Michael. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (2006).

- Koenig, Louis W. Bryan: A Political Biography of William Jennings Bryan (1971).

- Leinwand, Gerald. William Jennings Bryan: An Uncertain Trumpet (Lanham (MD), Rowman & Littlefield, 2006).

- Levine, Lawrence W. Defender of the Faith: William Jennings Bryan, The Last Decade, 1915–1925 (1965).

- Werner; M. R. Bryan (1929).

Specialized studies

- Barnes, James A. (1947). "Myths of the Bryan Campaign". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 34 (3): 367–404. doi:10.2307/1898096. JSTOR 1898096.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) on 1896 - Bensel, Richard Franklin. Passion and Preferences: William Jennings Bryan and the 1896 Democratic Convention (2008)

- Cherny, Robert W. (1996). "William Jennings Bryan and the Historians". Nebraska History. 77 (3–4): 184–193. ISSN 0028-1859.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) Analysis of the historiography. - Edwards, Mark (2000). "Rethinking the Failure of Fundamentalist Political Antievolutionism after 1925". Fides et Historia. 32 (2): 89–106. ISSN 0884-5379. PMID 17120377.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) Argues that fundamentalists thought they had won Scopes trial but death of Bryan shook their confidence. - Glad, Paul W. (1964). McKinley, Bryan and the People. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- Hohenstein, Kurt (2000). "William Jennings Bryan and the Income Tax: Economic Statism and Judicial Usurpation in the Election of 1896". Journal of Law & Politics. 16 (1): 163–192. ISSN 0749-2227.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - Jeansonne, Glen (1988). "Goldbugs, Silverites, and Satirists: Caricature and Humor in the Presidential Election of 1896". Journal of American Culture. 11 (2): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1988.1102_1.x. ISSN 0191-1813.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help) - Larson, Edward (1997). Summer for the Gods: The Scopes trial and America's continuing debate over science and religion. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07509-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Longfield, Bradley J. (2000). "For Church and Country: the Fundamentalist-modernist Conflict in the Presbyterian Church". Journal of Presbyterian History. 78 (1): 34–50. ISSN 0022-3883.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|month=(help) Puts Scopes in larger religious context. - Mahan, Russell L. (2003). "William Jennings Bryan and the Presidential Campaign of 1896". White House Studies. 3 (2): 215–227. ISSN 1535-4768.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - Murphy, Troy A. (2002). "William Jennings Bryan: Boy Orator, Broken Man, and the 'Evolution' of America's Public Philosophy". Great Plains Quarterly. 22 (2): 83–98. ISSN 0275-7664.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - Rove, Karl. (2015) The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters (2015), Detailed narrative of the entire campaign by Karl Rove a prominent 21st-century Republican campaign advisor.

- Scroop, Daniel (2013). "William Jennings Bryan's 1905–1906 World Tour". Historical Journal. 56 (2): 459–486. doi:10.1017/S0018246X12000520.

- Smith, Willard H. (1966). "William Jennings Bryan and the Social Gospel". Journal of American History. 53 (1): 41–60. doi:10.2307/1893929. JSTOR 1893929.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Taylor, Jeff (2006). Where Did the Party Go?: William Jennings Bryan, Hubert Humphrey, and the Jeffersonian Legacy. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1659-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) On Bryan's place in Democratic Party history and ideology. - Wood, L. Maren (2002). "The Monkey Trial Myth: Popular Culture Representations of the Scopes Trial". Canadian Review of American Studies. 32 (2): 147–164. doi:10.3138/CRAS-s032-02-01. ISSN 0007-7720.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)

External links

- United States Congress. "William Jennings Bryan (id: B000995)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by William Jennings Bryan at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Jennings Bryan at the Internet Archive

- William Jennings Bryan cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- "The Deity of Christ" – paper by Bryan on the subject

- William Jennings Bryan papers at Nebraska State Historical Society

- William Jennings Bryan Recognition Project (WJBP)

- "William Jennings Bryan, Presidential Contender" from C-SPAN's The Contenders

- 1860 births

- 1925 deaths

- United States Secretaries of State

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Nebraska

- Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees

- United States presidential candidates, 1896

- United States presidential candidates, 1900

- United States presidential candidates, 1908

- United States presidential candidates, 1912

- United States presidential candidates, 1920

- 20th-century American politicians

- Nebraska lawyers

- American Christian pacifists

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American Presbyterians

- American progressives

- American temperance activists

- Calvinist pacifists

- Christian creationists

- Christian fundamentalists

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- Illinois College alumni

- Bryan family (William Jennings Bryan family)

- Nebraska Democrats

- Nebraska Populists

- Newspaper people from Omaha, Nebraska

- Non-interventionism

- Northwestern University School of Law alumni

- Politicians from Jacksonville, Illinois

- People from Salem, Illinois

- Politicians from Lincoln, Nebraska

- People of the Philippine–American War

- People of the Spanish–American War

- Populism in the United States

- Progressive Era in the United States

- Scopes Trial

- William Jennings Bryan

- Woodrow Wilson administration cabinet members

- Newspaper founders

- American newspaper publishers (people)

- American newspaper editors

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery