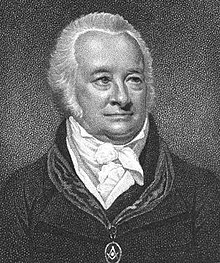

William Preston (Freemason)

William Preston (7 August 1742 – 1 April 1818) was a Scottish author, editor and lecturer, born in Edinburgh. After attending school and college he became secretary to the linguist Thomas Ruddiman, who became his guardian on the death of his father. On the death of Thomas, Preston became a printer for Walter Ruddiman, Thomas' brother. In 1760 he moved to London and started a distinguished career with the printer William Strahan. He became a Freemason, instituting a system of lectures of instruction, and publishing Illustrations of Masonry, which ran to several editions. It was under Preston that the Lodge of Antiquity seceded from the Moderns Grand Lodge to become "The Grand Lodge of All England South of the River Trent" for ten years. He died on 1 April 1818, after a long illness, and was buried in St Paul's Cathedral.

Early life[edit]

Preston was a born in Edinburgh, on 7 August 1742. His father, also William Preston, was a Writer to the Signet, a form of solicitor. His second, and only surviving child, was encouraged in Classical studies, entering the Royal High School, Edinburgh at six, where he shone in Latin, and would also have studied Greek. He continued his classical studies at college, before becoming secretary to Thomas Ruddiman, a classical scholar whose blindness now necessitated such help. Meanwhile, Preston senior's health and fortunes declined, due to bad investments and supporting the wrong side in the 1745 rebellion. On his death, in 1751, Ruddiman became young William's guardian. He was apprenticed to the printer, Walter Ruddiman, Thomas' brother, but until Thomas' death in 1757 spent most of his time reading to him, and transcribing and copy-editing his work.[1]

In 1760, furnished with letters of introduction by Ruddiman, Preston arrived in London, where he took employment with William Strahan, later to become the King's Printer, and a former pupil of the same school as Preston. Here he would spend his professional life as an editor, earning the respect of writers such as David Hume and Edward Gibbon.[2]

Freemasonry[edit]

Shortly after Preston's arrival in London, a group of Edinburgh Freemasons living in the English capital decided to form themselves into a lodge. The Grand Lodge of Scotland felt they could not grant them a constitution, as they recognised the jurisdiction of the Antients' Grand Lodge in the capital. They were accordingly constituted as Lodge no. 111 at the "White Hart" in the Strand on 20 April 1763. It may have been at this meeting that Preston became their second initiate. Unhappy with the status of the relatively new Grand Lodge which they found themselves part of, Preston and some others began attending a lodge attached to the original Grand Lodge of England, and persuaded their brethren to change allegiance. Accordingly, on 15 November 1764, Lodge no 111 of the Antients became Caledonian Lodge no 325 (now 134), under a constitution which was just starting to be known as the "Moderns";[1] that lodge later held its meetings at the Great Eastern Hotel on Liverpool Street in London.[3] Antient/ancient and Modern referred to the ritual used by the respective constitutions, not to the age of the Grand Lodges. The shift of allegiance occasioned some vitriolic correspondence between Caledonian Lodge and their former Grand Lodge.[4] Caledonian Lodge then became the major component in the first Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masonry.[5]

Preston soon began an extensive program of masonic research. Interviewing where he could, and entering into an extensive correspondence with Freemasons in Britain and overseas, he built a vast storehouse of masonic knowledge, which he applied initially to explaining and organising the lectures attached to the three degrees of Freemasonry. He met with friends once or twice a week to test and refine his presentation, and on 21 May 1772 he organised a Gala at the Crown and Anchor in the Strand at his own considerable expense, to introduce the Grand Officers and other prominent masons to his system. The success of his oration on that day led to the publication, later that year, of his Illustrations of Masonry, which ran to twelve English editions in the authors lifetime, as well as being translated into other languages. In 1774 he organised his material into lecture courses, delivered by him at the Mitre Tavern, Fleet Street. There were twelve lectures per degree, at one guinea per degree.[1][6]

Present at the Gala were two members of the Lodge of Antiquity (once, as the Goose and Gridiron, a founder of the Grand Lodge). John Bottomley was then the Master, and John Noorthouck a colleague of Preston at Strahan's printing firm. Antiquity was suffering from declining membership, and these two men conceived the idea of reviving their lodge by recruiting Preston. He was elected a member, in absentia, on 1 June 1774. On his first attendance as a member, a fortnight later, he was elected Master of the lodge. The lodge accordingly flourished, which somehow displeased Bro Noorthouck. He complained that the younger masons who now flocked to the lodge were all Preston's creatures, which had enabled him to stay in the chair for three and a half years.[1]

During this period, commencing in 1769, Preston became the Assistant Grand Secretary, and "Printer to the Society". This gave him access to material which he subsequently used in Illustrations of Masonry.[1] It also gave him the opportunity to attempt to drive a wedge between the Antients and the Grand Lodge of Scotland, by challenging the basis on which the younger Grand Lodge was formed. The attempt failed, and only served to widen the division between the two Grand Lodges.[4]

Schism from Grand Lodge[edit]

On 27 December 1777, some members of the Lodge of Antiquity, including Preston, returned from church wearing their masonic regalia. This amounted to little more than crossing the road. Certain of the original members of Antiquity who were not present (and who included the two men who had persuaded Preston to join Antiquity) chose to report the incident to Grand Lodge as a proscribed Masonic procession. Instead of playing down the occasion, Preston chose to defend the actions of himself and his brethren by emphasising the seniority of his own lodge. As the Goose and Gridiron, Antiquity had been one of the founders of Grand Lodge. Preston argued that his lodge had only subscribed to the original constitutions, and subsequent rulings did not apply to them. After due process, Preston and his supporters were expelled in 1779. This split Antiquity. The longer standing members stayed with the Moderns. The rest of the lodge allied itself with the Grand Lodge of All England at York, becoming for the period of their separation, "the Grand Lodge of All England South of the River Trent", warranting at least two lodges in its own right. In May 1789 the dispute was resolved, Preston, after an apology, was welcomed back to his Masonic Honours at a dinner, and the two-halves of the Lodge of Antiquity were re-united in 1790.[1][7]

Legacy[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Freemasonry |

|---|

|

Preston's expulsion from Grand Lodge signaled a great reduction in his contribution to Freemasonry. He had been absent from lodge for a year when he resigned in 1781. His brethren persuaded him to return five years later, which halted another period of decline. He claimed to have warranted several lodges in his period of exile in a rebel grand lodge, but only two have been verified. About the time of his re-admission to the Moderns, he founded the Order (or Grand Chapter) of Harodim, which was a vehicle for his own ideas about masonry as expressed in his lectures. This died out in about 1800. Preston took no part, and passed no public comment, in the long process of unification of the two Grand Lodges. His major masonic legacy must be considered to be his Illustrations of Masonry, which continued to new editions after his death, after a long illness, in 1818.[1][2]

While Preston is remembered as a masonic scholar, few modern masons have read his work. His history of freemasonry is every bit as far fetched as Anderson's, although it starts far later with Athelstan, and his lectures and explanations must be read as a work of its time, relating the Freemasonry of the late Eighteenth century to the people of that time.[8] Preston's lasting impact is in drawing the perception of Freemasonry away from the bar and the dining table, and giving it a more cerebral appeal.[9] Preston is also associated, with Grand Secretary James Heseltine and Thomas Dunckerley, with the movement of Masonic meetings from taverns into dedicated Masonic buildings.[10]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Phoenix Masonry Archived 20 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine Gordon P. G. Hills, Brother William Preston, an Illustration of the Man, his Methods and his Work. Prestonian Lecture, 1927

- ^ a b Masonic Dictionary Entry from Mackey's Encyclopedia of Freemasonry

- ^ Denslow, William R. (2004). 10,000 Famous Freemasons V3, K to P. pp. 365–66. ISBN 9781417975792.

- ^ a b Witham Matthew Bywater, Notes on Laurence Dermott G.S. and his Work, London, 1884

- ^ Camberley Lodge A.D. Matthews, An Historical Perspective on The Holy Royal Arch, Lecture July 2009, pdf Retrieved 18 September 2012

- ^ Masonic World Anon, William Preston, Short Talk Bulletin, February 1923

- ^ Pietre Stones H. L. Haywood, Various Grand Lodges, The Builder, May 1924

- ^ Masonic Dictionary Roscoe Pound, William Preston, The Builder, January 1915

- ^ Nebraska Masonic Education Andrew Prescott, A History of British Freemasonry 1425-2000, CRFF, University of Sheffield

- ^ archive.org Henry Sadler, Thomas Dunckerley, his Life, Labours and Letters.

Preston's writings[edit]

- Preston, William (1772). Illustrations of Masonry (1st ed.). J. Wilkie.

Further reading[edit]

- Dyer, Colin (1987). William Preston and His Work. Lewis Masonic. ISBN 0-85318-149-7.

- Davis, Robert G. (2009), "William Preston: Architect of the American Craft Ritual", Philalethes, 62 (4): 82–89, 112–114

External links[edit]

- Illustrations of Masonry on Google Books