Louise Cox (painter)

Louise Cox | |

|---|---|

Cox circa 1890. Photo by Rockwood. | |

| Born | Louise Howland King June 23, 1865[1] |

| Died | December 11, 1945 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | |

| Known for | Painting |

| Spouse | Kenyon Cox (1892–1919, his death)[2] |

Louise Howland King Cox (June 23, 1865—1945) was an American painter known for her portraits of children. She won a number of prizes throughout her career, notably a bronze medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition and a silver medal at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo.[2]

Early and personal life[edit]

Louise Howland King was born in San Francisco, California, on June 23, 1865,[3] to Anna Stott and James King.[4] Her family moved to New York when she was a child.[5] In 1872, Anna King had sued her husband for divorce, citing cruel and inhumane treatment.[6][7] James C. King was convicted for a murder related to that suit in November 1872.[7][8] In 1880, when she was 14, Louise attended small school of Lucy McGuire in Dover, New Jersey. When she first attended art school she lived with her mother and sister Pauline.[9]

On June 30, 1892, she wed her former teacher Kenyon Cox in Belmont, Massachusetts, at the home of her aunt,[10][11] Mrs. B.M. Jones.[12] Kenyon, who had thought he might be a lifelong bachelor, realized that he was in love with Louise, but he did not express his feelings for some time. They wrote long letters to each other during the period that she was a teacher in Toledo, Ohio.[13] In a letter that he wrote to her in 1887, he commended her artistic talent and expressed his belief that she would have a successful career and said:

I am glad to find that you count enough upon my interest in your work and progress to let me know where you are and what you are doing. You are quite right to count upon it... If I can ever be of use to you in recommending you as a teacher or in any other way, do not fail to command me. Above all, my criticism or advice, such as it is, you will always have.[5]

That same year he declared her to be his best student.[14] In January 1892, after she had returned to New York, the couple became engaged and both became like "moonstruck youngsters".[13] Kenyon Cox wrote his mother, "Long before I felt the thrill of love, I knew that she would make the best wife in the world for me if I should love her . . . When love came to add to the friendship and confidence, I felt safe and so we mean to marry as soon as we can."

They both exhibited their works at the National Academy of Design and the Society of American Artists. In April 1893, Louise suffered a miscarriage and the couple sailed for Europe about the SS Maasdam weeks before their first anniversary. The trip, partly for her emotional recuperation, included travel to Paris, Italy, and the Netherlands.[15]

They had three children. Leonard, born in 1894 and named after Leonard Opdycke, was a World War I war hero and had a career in city planning and architecture. Son Allyn, born two years later, became an artist, particularly noted for his mural paintings, and an interior decorator. Daughter Caroline born in 1898 was also a talented artist.[11][16]

The family lived in New York City on East 67th Street and in 1910 Louise's mother, Anna T. King, a writer, lived with them.[17] Cox enjoyed gardening. She did not support the Women's suffragette movement.[4] Cox lived in Italy, Hawaii, and a northern suburb of New York following the death of her husband.[16] She lived in Honolulu, Hawaii by 1930[18] and as late as 1935. In 1940 she lived on Roaring Brook Road on New Castle, Westchester, New York. At that time she was 74 years of age and still operated and painted in a studio.[19] She died December 11, 1945, in Windham, Connecticut. She was cremated, as was her husband Kenyon, and their ashes were scattered together at Cornish, New Hampshire where they spent their summers.[3]

-

Louise Howland King, about 1868

-

Louise and Kenyon Cox, 1896

-

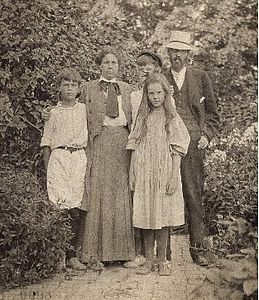

Allyn, Louise, Leonard, Caroline and Kenyon Cox, about 1906

Education[edit]

With financial help from an aunt in Boston,[9] Louise Cox attended the National Academy of Design in New York City, and is quoted as saying, "Although I was born in 1865 in San Francisco, it was not until sixteen years later that I started to live, for in 1881 I entered the National Academy of Design."[20] During her time at the National Academy of Design, Louise Cox learned an academic style of painting, grounded in the style of Jean-Léon Gérôme (One of her instructors, Professor Lemuel Wilmarth, was taught by Gérôme). According to Cox, the Gérôme principles "were based on study, thoroughness, and self-discipline" and her "grounding in the Gérôme tradition prevented my taking on the arty methods in vogue".[20]

She left after two years to enroll with the Art Students League,[21] partially supported by a friend of her mother,[9] and studied under Thomas Dewing.[16] She received a less traditional education at the League, which was unendowed and run by students. Some classes were held collaboratively by the students alone. During a student-led sketching class she quickly learned to interpret and understand forms, which she said "helped me in my later portrait painting of young, active children"[20] Students sometimes dressed in mythic and historic costumes, which became the subject of her paintings.[14]

It was at the Art Students League that Louise Cox met her art instructor and future husband, Kenyon Cox. Having a solid reputation at the League, Kenyon Cox was selected as the 1885 instructor for the women's life class.[20] Her other instructors included J. Alden Weir, George de Forest Brush, and Charles Yardley Turner.[21] She was considered an attractive, industrious student with a good sense of humor.[22]

Career[edit]

Cox's first renowned painting was The Lotus Eaters, which was displayed at the National Academy of Design in 1887, the Paris Exposition in 1889,[2] and with A Rondel at the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.[23][2][24] In 1893 Cox displayed the painting, Psyche at an annual exhibition for the Society of American Artists. She was elected a member in the same year.[25] The National Academy of Design awarded her the 1896 Third Hallgarten Prize for Pomona, and the 1904 Second Hallgarten Prize for The Sisters.

Beginning in 1896 Louise and Keynon Cox spent the summers with their children in the country's first major artist colony, the Cornish Art Colony in New Hampshire.[26] At Cornish she made paintings of her children and local children, some of which were commissioned portraits.[27]

She was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1902.[4] She also became a member of the Woman's Art Club of New York.[28]

She painted still life, ideal figures, and portraits but was best known for her portraiture of children.[16][28][29] Her works are in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.,[4] High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and the National Academy of Design in New York, New York.[30] Cox also carved wood and was a photographer.[27] She was considered among the "outstanding stained-glass artists," such as Wright Goodhue, David Maitland Armstrong and William Willet.[31]

-

A Lady, in profile to the left before an Arts and Crafts background

-

A Rondel, 1892, oil on canvas,

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia -

Louise Cox, The Rose, 1898

-

Portrait of Leonard Cox, 1895, Smithsonian American Art Museum

-

Allyn Cox in Infancy, 1898, National Academy of Design, New York

-

May Flowers, 1911, Smithsonian American Art Museum

-

Portrait of a Young Boy in a Sailor's Costume, 1912

Awards[edit]

- 1896 — Third Hallgarten prize of the National Academy of Design for Pamona[2][28]

- 1900 — Bronze medal at the Paris Universal Exposition[4]

- 1901 — Silver medal at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York[32]

- 1903 — Julia Shaw Memorial prize from the Society of American Artists.[2][4]

- 1904 — Silver medal from the St. Louis Exposition in 1904.[2]

- 1904 — Second Hallgarten prize of the National Academy of Design.[32]

Works[edit]

- A Rondel, 1892, oil on canvas, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia[30]

- Allyn Cox, 1940, oil on canvas, National Academy of Design, New York, New York[30]

- Allyn Cox in Infancy, 1898, oil on canvas, National Academy of Design, New York, New York[30]

- Angiola, 1897[28]

- May Flowers, 1911, oil on canvas, 24 1/8 × 20 1/8 in. (61.2 × 51.0 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of William T. Evans [29]

- Mural Study, 1892, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, District of Columbia[30][33]

- Pamona[28]

- Portrait of Leonard Cox, 1895, oil on canvas, 11 3/4 × 12 in. (29.8 × 30.5 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[34]

- Portrait of a Young Girl, oil, Lagakos-Turak Gallery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[30]

- Portrait of Mrs. John Larkin, 1903[35]

- Portrait of the Artist's Daughter, oil on canvas, private collection[30]

- Psyche, 1893[28]

- The Fates, 1894[28]

- Untitled (Child with Sun Dial), c. 1903, pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[33]

- Untitled (Draped Female Figure), c. 1903, pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[33]

- (Untitled-nude female figure), c. 1903, pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[33]

- Untitled (Seated Draped Female Allegorical Figure), c. 1903, pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[33]

- Untitled (Seated Draped Female Figure, Profile), c. 1903, pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[33]

- Untitled (Seated Young Girl), 1903, pencil and pastel on paper, 15 7/8 × 10 3/8 in. (40.2 × 26.5 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[36]

- Untitled {Young Man with Lute}, c. 1903, pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Allyn Cox[33]

References[edit]

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. pp. 301–302.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mrs. Kenyon Cox, Portrait Painter: Artist's Widow, Recipient of Many Prizes, Dies—Known for Work with Children". The New York Times. December 12, 1945. p. 26.

- ^ a b "Louise Cox". American Art Museum. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f John William Leonard. Woman's Who's who of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Women of the United States and Canada, 1914-1915. American Commonwealth Company; 1914. p. 211.

- ^ a b Kenyon Cox. An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919. Kent State University Press; January 1995. ISBN 978-0-87338-517-6. p. 86.

- ^ The Courts: Civil Notes. New York Herald-Tribune. August 31, 1872.

- ^ a b "The Pine Street Murder: Inquest by Coroner Herrman on the Body of O'Neil. Evidence of the Murdered Man's Wife A Verdict Against King Extraneous Evidence Excluded by the Coroner." New York Times. Article about November 18, 1872 murder. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- ^ "Domestic News". Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 44, Number 6749, November 19, 1872.

- ^ a b c Howard Wayne Morgan. Kenyon Cox: 1856-1919 : a Life in American Art. Kent State University Press; January 1994. ISBN 978-0-87338-485-8. pp. 124-125.

- ^ "Certificate of Marriage". Archives of American Art. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ a b Kenyon Cox. An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919. Kent State University Press; January 1995. ISBN 978-0-87338-517-6. p. 16.

- ^ Howard Wayne Morgan. Kenyon Cox: 1856-1919 : a Life in American Art. Kent State University Press; January 1994. ISBN 978-0-87338-485-8. p. 129.

- ^ a b Kenyon Cox. An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919. Kent State University Press; January 1995. ISBN 978-0-87338-517-6. pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Howard Wayne Morgan. Kenyon Cox: 1856-1919 : a Life in American Art. Kent State University Press; January 1994. ISBN 978-0-87338-485-8. p. 126.

- ^ Kenyon Cox. An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919. Kent State University Press; January 1995. ISBN 978-0-87338-517-6. p. 85, 118.

- ^ a b c d Ann Lee Morgan Former Visiting Assistant Professor University of Illinois at Chicago. The Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists. Oxford University Press; 27 June 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-802955-7. p. 102.

- ^ Kenyon and Louise Cox. Manhattan Ward 19, New York, New York. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Louise Cox, born June 23, 1865 in San Francisco. Sailed on the SS Matsonia July 2 to July 8, 1930. Home address listed as Honolulu. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Honolulu, Hawaii, compiled 02/13/1900 - 12/30/1953; National Archives Microfilm Publication: A3422; Roll: 109; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787 - 2004; Record Group Number: RG 85.

- ^ Louise Cox, Artist, born in California. 1940 United States Federal Census. United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940.

- ^ a b c d Richard Murray; Louise Howland King Cox (1987). "Louise Cox at the Art Students League: A Memoir". Archives of American Art Journal. 27 (1). The Smithsonian Institution: 16–17.

- ^ a b Louise Howland King Cox. Archived 2016-04-07 at the Wayback Machine National Academy Museum. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Kenyon Cox. An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919. Kent State University Press; January 1995. ISBN 978-0-87338-517-6. p. 15.

- ^ Nichols, K. L. "Women's Art at the World's Columbian Fair & Exposition, Chicago 1893". Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ Howard Wayne Morgan. Kenyon Cox: 1856-1919 : a Life in American Art. Kent State University Press; January 1994. ISBN 978-0-87338-485-8. p. 134.

- ^ Dearinger, David (2004). Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design. Hudson Hills. p. 131.

- ^ Howard Wayne Morgan. Kenyon Cox: 1856-1919 : a Life in American Art. Kent State University Press; January 1994. ISBN 978-0-87338-485-8. p. 185.

- ^ a b Steve Shipp. American Art Colonies, 1850-1930: A Historical Guide to America's Original Art Colonies and Their Artists. Greenwood Publishing Group; 1996. ISBN 978-0-313-29619-2. p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g John Howard Brown. Lamb's Biographical Dictionary of the United States: Chubb-Erich. James H. Lamb Company; 1900. p. 217.

- ^ a b "Mayflowers". Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- ^ a b c d e f g Search: Louise Cox. SIRIS. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Edward F. Bergman. The Spiritual Traveler: New York City : the Guide to Sacred Spaces and Peaceful Places. Hidden Spring; 1 January 2001. ISBN 978-1-58768-003-8. p. 77.

- ^ a b Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution Press; 1916. p. 127.

- ^ a b c d e f g Search: Louise Cox". Collections. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- ^ "Portrait of Leonard Cox". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Kenyon Cox. An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919. Kent State University Press; January 1995. ISBN 978-0-87338-517-6. p. 141.

- ^ "Untitled (Seated Young Girl)". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

Further reading[edit]

- Sarah Burns; John Davis. American art to 1900: a documentary history. University of California Press; 2009. ISBN 978-0-520-24526-6. pp. 842–843.