Mark Essex

Mark Essex | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mark James Robert Essex August 12, 1949 Emporia, Kansas, U.S. |

| Died | January 7, 1973 (aged 23) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Resting place | Maplewood Memorial Lawn Cemetery, Emporia, Kansas, U.S. |

| Other names | The New Orleans Sniper Mata[3] |

| Parent(s) | Mark Henry Essex Nellie (née Evans) Essex |

| Motive | Racial hatred[1] Rage |

| Details | |

| Date | December 31, 1972, and January 7, 1973 |

| Location(s) | New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Target(s) | New Orleans Police Department Caucasians |

| Killed | 9 |

| Injured | 12 |

| Weapons | |

Mark James Robert Essex (August 12, 1949[4] – January 7, 1973) was an American serial sniper and black nationalist known as the "New Orleans Sniper" who killed a total of nine people, including five police officers, and wounded twelve others, in two separate attacks in New Orleans on December 31, 1972, and January 7, 1973. Essex was killed by police in the second armed confrontation.[3]

Essex is believed to have specifically sought to kill white people and police officers due to racism he had previously experienced while enlisted in the Navy. His increasingly extremist anti-police, black supremacist, and anti-white views are believed to have solidified following a November 1972 violent clash between Baton Rouge sheriff's deputies and student civil rights demonstrators, during which two young black demonstrators were shot and killed.[5]

Early life[edit]

Mark James Robert Essex was born in Emporia, Kansas, the second of five children born to Mark Henry and Nellie (née Evans) Essex. He was raised in a close-knit and religious household. His father was a foreman in a meat-packing plant and his mother counseled preschool-age children in a program for disadvantaged children.[6]

Emporia, the community in which Essex was raised, consisted of 19,000 people[7] and prided itself in a long tradition of racial harmony. As a child and adolescent, Essex had numerous friends of all races and seldom, if ever, encountered any form of racism.[6]

As a child, Essex developed a passion for the Cub Scouts and an aptitude for music — playing the saxophone in his high school band. He also developed a passion for hunting and fishing in the rivers and streams within and around the city, and developed ambitions to become a minister in his teens.[8]

Adolescence[edit]

Essex was popular among his high school peers, and refrained from trouble as a teenager. His sole brush with Emporia police occurred in 1965, when an officer incorrectly assumed Essex—who stood just 5 ft 4 in (160 cm) tall—was too young to drive. He is known to have dated both black and white girls in high school, on one occasion telling his mother he did not "see much difference" between girls of different races. An average student who performed best in technical subjects, Essex graduated from Emporia High School in 1967.[9]

Shortly after graduating from high school, Essex briefly enrolled at Emporia State University. He dropped out after just one semester, and briefly worked in the same meat-packing plant as his father as he considered his next career or educational move. Concluding his horizons were limited in Emporia, shortly after his 19th birthday, Essex decided to enlist in the United States Army. Upon the advice of his father, a World War II veteran, he instead opted to join the Navy and seek vocational training.[10]

[edit]

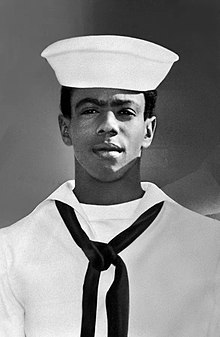

Essex enlisted the Navy on January 13, 1969, committing himself to a four-year contract at advanced pay. Within three months, he was assigned to the Naval Air Station at Imperial Beach, California. His family would later reflect that, as Essex prepared to enlist, he was "happy go lucky".[11]

Initially, Essex's experiences in the Navy were positive. He performed his compulsory training at the Naval Training Center with exemplary results. His superiors recommended he enroll in the Navy Dental Center. Essex accepted this advice and was apprenticed as a dental technician in April 1969, specializing in endodontics and periodontics.[12] He soon formed a close and ongoing friendship with his white supervisor, Lieutenant Robert Hatcher. However, Essex soon learned that bigotry from many of the white servicemen towards blacks (both overt and discreet) was a general everyday occurrence for blacks serving within the Navy. Shortly after his enlistment, Essex obtained a job as a bartender at an enlisted men's club named the Jolly Rotor, where he discovered that certain rooms were off-limits to blacks.[13] In one letter to his mother, Essex wrote his experiences of racial relations within the Navy were "not like [he] thought [they] would be. Not like Emporia. Blacks have trouble getting along here."[14]

Throughout 1969, Essex suffered these indignities quietly—apparently believing what he had been told by other black sailors: that he would be treated better once he achieved a higher rank.[15] Within a year, he had risen to the rank of seaman, although the harassment continued, and he began taking sedatives. Shortly thereafter, Essex formed a close friendship with a black colleague named Rodney Frank; a self-described black militant who worked in the Aircraft Intermediate Maintenance Department. The two regularly socialized in their off-duty hours, and by the summer of 1970, Essex had become markedly radicalized. Frank also encouraged Essex to read literature about individuals such as Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, who together had founded the Black Panther Party.[16]

Several months after Essex's acquaintance with Frank, in August 1970, he became involved in a physical altercation with a white NCO moments after hearing the individual state his belief "how beautiful" it must have been in decades past when "a nigger went to sea it was below decks, in the galley".[17] Although Essex and his adversary agreed to a compromise to avoid either being admonished for the altercation, the fact he had struck a white sailor of senior rank increased the level of harassment and intimidation he was subjected to from white personnel. Two months later, on the morning of October 19, Essex went absent without leave (AWOL) from the Navy. He phoned his mother from a bus station, informing her: "I'm coming home. I've just got to have some time to think."[18]

AWOL[edit]

Essex returned via a Greyhound bus to Emporia, and remained AWOL until November 16, 1970. While AWOL, he repeatedly described to his family his experiences of overt discrimination at the hands of many of the white Navy sailors, his overt bitterness, and his resultant growing hatred towards the white race. Although his family attempted to reason with Essex against this viewpoint, Essex exclaimed: "What else is there? They take everything from you. Your dignity, your pride. What can you do but hate them?"[19]

One month after his desertion from the Navy, Essex's family persuaded him to return to Imperial Beach. Prior to doing so, Essex ensured he spoke to Lieutenant Hatcher, to whom he explained his reasons for his desertion. Hatcher's official notes state Essex informed him: "I don't want to have anything more to do with the Navy. It wouldn't be fair, not to you or the (dental) patients. The bad atmosphere would affect my work. The work is the only thing on this base I like." He then agreed to plead guilty to the charge of desertion.[20]

At the subsequent hearing, Hatcher provided a vigorous defense of his protégé, praising his work ethic and stating the decision for his desertion had been influenced solely by ongoing racial discrimination. The judge conceded these factors were the cause and sentenced Essex to a lenient punishment of thirty days' restriction to base and forfeiture of $90 of his pay (the equivalent of about $710.00 as of 2023)[21] for two months.[20]

Military discharge[edit]

Radicalization[edit]

Essex was given a general discharge from the Navy for general unsuitability on February 11, 1971, at the age of 21. This experience embittered Essex as he felt he had been unfairly stigmatized by the Navy, who had known only too well the discrimination he had endured. This led him to continue exploring Black Panther ideology.[22] He soon began referring to himself as "Mata",[n 1] and embraced the extremist content of the 1968 book Black Rage.[3][23]

Emporia[edit]

Sometime around late-April 1971, Essex returned to his family in Emporia. Two months later, he purchased a Ruger .44-caliber semi-automatic carbine via mail-order from an Emporia Montgomery Ward outlet. Upon receiving the weapon several weeks later, he began incessantly target shooting in the countryside around Emporia in efforts to improve his marksmanship. That August, he abruptly left his family home without even informing his parents and drove to Louisiana. The precise reason for his relocation is unknown, although he may have chosen to relocate to this city to become reacquainted with Rodney Frank.[24][n 2]

New Orleans[edit]

Essex moved home four times between 1971 and 1972 before relocating to a two-room apartment at 2619 Dryades Street in Central City in early November 1972, and saw first-hand the poverty of those living in the city's housing projects.[26] On August 22, 1972, he applied for admittance into the Total Community Action (TCA) federally funded program. He was accepted into the program, and chose to enroll in classes specializing in vending machine repair. Essex quickly rose to the top of his class.[27] He also began a course of African studies in 1972, and would memorize African terms and dialects as he sat alone in his apartment.[28][29] Many of the words, phrases and hate slogans he familiarized himself with—in English, Swahili, and Zulu—would be daubed across the walls and ceilings of his apartment.[30]

By the summer of 1972, Essex had acquired a further firearm: a Colt .38-caliber revolver. He was also living an increasingly solitary existence,[31] and battling severe depression.[32]

In September 1972, the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) announced the formation of the Felony Action Squad, aimed at reducing the number of violent crimes in the city. In a press statement, Superintendent Clarence Giarrusso stated that, if threatened in any way, members of this action squad were authorized to shoot to kill.[33][n 3] The following month, Essex paid a surprise visit to his family in Emporia. His demeanor was upbeat and enthusiastic, leading his parents to believe he had recovered from his bitter experiences in the Navy.[34]

Southern University civil rights shootings[edit]

On November 16, Essex learned that two African American students had been shot to death by East Baton Rouge Parish sheriff's deputies during a campus demonstration at Southern University (a historically black university) in the Scotlandville neighborhood of Baton Rouge.[35] Essex was disturbed and outraged by the harsh response of police to this student civil rights demonstration. This incident is believed to be that which fueled his decision to act against police oppression.[36]

Shortly after this incident, Essex penned a letter to his mother in which he wrote: "Africa, this is it, mom. It's even bigger than you and I, even bigger than God. I have now decided that the white man is my enemy. I will fight to gain my manhood or die trying. Love, Jimmy."[3] On Christmas Day, he ate dinner with the family of a fellow student from the TCA program.[26] That evening, Essex phoned his family. He made a specific point of talking to each family member in succession, and conveyed no sense of distress. Over the following days, Essex gave away most of his possessions to acquaintances and neighbors, falsely claiming he intended to return to Emporia.[36]

Days before New Year's Eve, Essex wrote a letter addressed to WWL-TV, signed "Mata", in which he described his intentions to attack the New Orleans Police Department on December 31. He cited the primary justification for his impending attack as being vengeance for the deaths of the "two innocent brothers" killed in the Southern University civil rights demonstration the previous month.[37]

Sniper attacks[edit]

New Year's Eve 1972[edit]

At approximately 10:55 p.m. on New Year's Eve 1972, Essex parked his car and walked along Perdido Street, a block from the NOPD, armed with his Ruger .44-caliber semi-automatic carbine, his .38-caliber revolver, a large supply of ammunition, a gas mask, wire cutters, lighter fluid, matches, and a string of firecrackers all stashed inside a green duffel bag.[38] He hid behind parked cars in a poorly illuminated parking lot across from the busy central lockup and began firing at a 19-year-old cadet, named Bruce Weatherford, as he walked toward the gatehouse to report for duty.[39] Weatherford instinctively dove for cover behind a parked car, and then turned to see the fellow cadet he was relieving, 19-year-old Alfred Harrell, run across the sally port to his aid. Essex then shot Harrell once through the chest. He also wounded Lt. Horace Pérez in the attack; Pérez was wounded in the ankle by the same bullet which struck Harrell and ricocheted off a wall.[40] Harrell was black; before beginning his attacks, Essex had specifically stated his intention to kill "just honkies."[38][n 4]

Having fired six rounds in this initial stage of his attack, Essex evaded capture by climbing a chain link fence and running across the I-10 expressway, having detonated several firecrackers as a diversion. He ran into an industrial area of Gert Town; an area known for high crime and hostility towards police. There he first attempted to gain entrance to a building located at 4100 Euphrosine Street by shooting four .44 rounds from his carbine at the door before successfully breaking into the Burkart Manufacturing Building; a warehouse and manufacturing plant on the corner of Euphrosine and South Gayoso. Intentionally or otherwise, this action activated an alarm that alerted police to this break-in. A K-9 unit, led by Officers Edwin Hosli Sr. and Harold Blappert, responded to the call. Neither realized this incident was connected to the earlier attack on central lockup.[42]

The two officers circled the building, looking for signs of forced entry before parking in front of the building. As Officer Hosli exited his vehicle to retrieve his German Shepherd from the car's back seat at 11:13 p.m., Essex shot him once in the back.[43] Officer Hosli would die of his injuries on March 5.[42][29]

Essex then fired several further rounds at the car, shattering the windshield. Officer Blappert reached for the radio on the front seat and called for back-up. Blappert then fired four shots at the spot where he saw muzzle flashes from Essex's rifle, then he pulled his partner onto the front seat and waited for back-up. Within minutes of Blappert's call, over thirty armed police officers arrived at the warehouse; they sent two dogs into the building to search for Essex, but he had already escaped. Spots of blood on the ground beside a discarded Colt .38 revolver, multiple discarded rounds of live ammunition, and a bloody hand print found upon a window sill within the Burkart Building indicated Essex had received a wound—likely not a serious one—in his exchange with Blappert.[44]

Initial manhunt[edit]

Although police extensively searched the neighborhood for the sniper(s), and conducted house-to-house searches, their quarry had escaped. The search ended shortly after 9 a.m. on January 1, 1973, following complaints from several local residents pertaining to officers' heavy-handed tactics.[39]

The decision to terminate the search for the perpetrator(s) was made moments after police discovered two carefully placed live rounds pointing at the doors of the 1st New St. Mark Baptist Church (approximately two blocks from the Burkart Building).[45]

January 1–6, 1973[edit]

At 9 p.m. on January 1, the pastor of the 1st New St. Mark Baptist Church entered his place of worship to find a young, armed black male inside. The pastor fled to a neighbor's house and called police, although by the time police arrived, the individual had fled. A subsequent police investigation would determine Essex later returned to the church and remained at this site until January 3. He was observed by a 33-year-old local grocer named Joseph Perniciaro entering his premises, Joe's Grocery, with a bloodstained bandage on his left hand on the evening of January 2. Perniciaro sold several provisions including food and a razor to Essex. Convinced Essex was involved in nefarious behavior, Perniciaro then ordered his stock boy to follow him. The stock boy reported Essex had walked across the street and into the local church.

Perniciaro reported this information to police. When police arrived to search the premises on the evening of January 3, Essex had fled, although bloodstains and food wrappings indicated a wounded individual had been living in the premises for a short period of time. A bag containing several .38 caliber cartridges was also found hidden in a bathroom alongside a letter penned by Essex to the minister apologizing for breaking into the church.[46]

Essex's movements between the evening of January 3 and the morning of January 7, 1973, are unknown, although an official police investigation later concluded he had not returned to his apartment and was most likely hiding at an unknown location close to the church.[47]

January 7, 1973[edit]

At 10:15 a.m. on January 7, 1973, Essex returned to Joe's Grocery and shouted to Joseph Perniciaro, "You! Come here!" When Perniciaro attempted to flee, Essex shot and severely wounded him with his .44 Magnum carbine. He then carjacked a 30-year-old black motorist named Marvin Albert as he sat in his 1968 Chevrolet Chevelle outside his house on South White Street, shouting: "Hi brother. Get out [of] the car. I don't want to kill you, but I'll kill you too!"[48]

Essex drove Albert's vehicle to the 17-story Downtown Howard Johnson's Hotel at 330 Loyola Avenue in New Orleans' Central Business District, across the street from City Hall and Orleans Parish Civil District Court. He parked the vehicle on the fourth level of the hotel's garage and climbed the fire escape stairs directly across from the garage in an effort to gain illegal entry via an unlocked door, but each successive door he attempted to open, he discovered to be locked. As Essex attempted to enter the eighth floor via this method, he exclaimed to two hotel maids: "Let me in, sisters. I've got something to do." The two women refused, citing hotel regulations. As Essex ran up the stairs to the ninth floor, the two women observed the rifle in his hands and ran to alert management of the impending threat.[41]

Gaining entry to the hotel via a door on the 18th and top floor[n 5] which had been propped open with a stack of linen, Essex first encountered three African American employees of the hotel. He immediately said to one of these individuals: "Don't worry, sister. We're only shooting whites today." These employees also ran to notify authorities.[49]

In the hallway by room 1829, Essex encountered 28-year-old Dr. Robert Steagall, who observed Essex and exclaimed, "What are you doing?" As Essex raised his rifle, Steagall lunged at him.[50] Following a brief struggle in which he was shot through the arm, Steagall was knocked to the floor and fatally shot through the chest.[51] His 25-year-old wife, Elizabeth, screamed "Please don't kill my husband!" As she attempted to cradle her husband's body, Essex shot her once through the base of her skull, killing her almost instantly.[42]

Essex then entered the Steagalls' room; he soaked telephone books with lighter fluid and set them ablaze beneath the curtains before dropping a Pan-African flag onto the floor beside the bodies of the couple as he ran toward one of the hotel's interior stairwells.

On the 11th floor, Essex entered several vacant rooms and ignited more fires—likely by burning bedding within the rooms (the draperies within the hotel rooms were fire retardant). He also shot and killed the hotel's assistant manager, 62-year-old Frank Schneider,[52] who had proceeded to the 11th floor to investigate employees' reports of an armed intruder on this floor. Immediately prior to encountering Essex, Schneider and a porter named Donald Roberts had exited an elevator before a hysterical black maid named Beatrice Greenhouse attempted to warn the two men of the intruder's intentions. As both turned to run, Essex raised his rifle and fatally shot Schneider in the back of the head; Roberts reached the safety of a nearby stairwell. He ran to a payphone and notified police.[53]

Essex then ignited another fire on the 11th floor before descending to the 10th floor, where he encountered the hotel's general manager, Walter Collins, attempting to warn guests about the spreading fires. Essex shot and fatally wounded Collins, who shouted to a guest to shut her door and call the police. Collins then crawled to a stairwell. He would die of his injuries on January 26.[54]

Police response[edit]

Shortly after 11 a.m., two young patrolmen named Michael Burl and Robert Childress arrived at the hotel in response to initial reports of an armed individual roaming the premises. The two began an ascending floor-to-floor search. On one of the lower floors, they encountered Beatrice Greenhouse, who informed them the perpetrator was on one of the upper floors. In an error of judgment, the two ascended to the 18th floor in an elevator, which halted close to the top floor due to smoke in the elevator shaft. At about the same time, Essex shot 43-year-old hotel guest and broadcasting executive Robert Beamish in the stomach as he walked close to the eighth-floor swimming plaza. Beamish fell into the swimming pool, but he realized he was not badly hurt. He remained in the water for almost two hours before he was rescued.[55]

By 11:20 a.m. scores of police officers and firefighters had converged at the hotel,[n 6] and Superintendent Giarrusso had established a command post on the ground floor of the hotel. Giarrusso ordered marksmen deployed at various strategic positions around the hotel. Within the hour, he ordered a room-by-room search for the perpetrator. Several firefighters attempted to rescue guests who had fled to the hotel balconies to escape both the gunman and the numerous fires he had started; efforts to rescue these individuals were hampered both by Essex pinning down emergency responders to the scene with his firearm, and conflicting descriptions as to his height and clothing which led responders to believe there may be more than one gunman.[31]

One of the first firemen to arrive at the hotel, 29-year-old Timothy Ursin, attempted to ascend to a balcony to rescue guests; he was followed by two patrolmen—one of whom observed Essex lean from a balcony and shoot Ursin through the shoulder. Ursin fell into the arms of one patrolman as his colleague—further down the ladder—returned fire at Essex. Ursin would survive, although he would lose one of his arms. As paramedics placed Ursin in an ambulance, Essex wounded 20-year-old Christopher Caton, the driver, with a shot in the back.[56]

Minutes later, a patrolman named Charles Arnold obtained a strategic position offering a prime view of the hotel from an office complex across the street. As Arnold opened a window to afford a clear view, a single bullet tore into his jaw, sending him sprawling backwards onto a desk. Arnold pressed a towel against his wound and walked to the nearby Charity Hospital to seek treatment for his wound. He would also survive his injury.[31] Shortly thereafter, Essex shot and wounded a 33-year-old sheriff's deputy named David Munch in the leg and neck as he also took aim at the hotel from the eighth floor of the nearby Rault Center.[49]

At 11:55 a.m., patrolmen Kenneth Solis and David McCann attempted to dispel a crowd of spectators from a plaza north of the hotel. As the two walked from beneath a canopy of trees to reach a crowd of onlookers, Solis was shot in the right shoulder, with the bullet exiting beneath his lower rib cage.[5] McCann immediately carried Solis back beneath the view of the tree canopy and out of Essex's view. As Solis fell, a 43-year-old police officer named Emanuel Palmisano ran to his aid, only to be shot in his arm and back. A 26-year-old patrolman named Phillip Coleman—responding to Palmisano's cries for help—drove his patrol car onto the plaza. As Coleman rolled out of the driver's seat and opened the rear door in order that Palmisano and Solis could be transported to Charity Hospital, Essex fatally shot him in the head.[57][n 7]

Essex then descended to the fourth floor parking lot, possibly with intentions to flee the hotel in the vehicle he had stolen that morning. Here he shot at, and missed, two police officers he observed standing guard inside the hotel's parking lot. He then returned to the 16th floor where he observed a 33-year-old traffic officer named Paul Persigo attempting to divert onlookers to safety outside the hotel. Essex fatally shot Persigo in the mouth.[57] According to several eyewitnesses, Persigo staggered several feet before falling to the sidewalk. He was pronounced dead on arrival at Charity Hospital.[58]

Shortly after noon, Deputy Superintendent Louis Sirgo organized a rescue party of three men to free patrolmen Burl and Childress, who were believed still to be trapped inside an elevator shaft close to the 18th floor.[42][n 8] At approximately 1:07 p.m., while approaching the 16th floor, Sirgo and his colleagues heard what they believed to be a police whistle sourcing from this floor. Believing this whistling sound to source from the two trapped patrolmen, the four officers ascended further. As Sirgo turned the final corner of the staircase, Essex shot him once at almost point-blank range through the chest, exposing his spine and causing Sirgo to fall backwards onto his colleagues. Essex immediately turned and ran in the direction of the hotel roof. Sirgo would be pronounced dead on arrival at Charity Hospital.[59]

Final standoff[edit]

At approximately 2 p.m., Essex—by this stage having depleted his portable cache of firecrackers and ammunition[60]—took cover in a concrete cubicle on the southeast side of the hotel roof. Over the following hours, he repeatedly shot at a CH-46 military helicopter piloted by Lt. Colonel Charles Pitman, a pilot in the United States Marine Corps who, without obtaining prior clearance, had flown to the location to assist police in their efforts to kill the sniper or snipers. Pitman first landed the helicopter near the hotel, allowing five police sharpshooters to board. This helicopter subsequently performed several strafe runs over the hotel roof over the following hours, and Pitman later stated his hope to at least strike Essex with a ricochet, although it is unknown whether Essex was wounded in any of these exchanges. In each instance Pitman flew away from the hotel to reload, Essex returned fire at the helicopter.[n 9]

Initially, Superintendent Giarrusso was reluctant to place any further officers at risk of injury or death by deploying them to the hotel roof. His strategy was to keep the sniper pinned in the cubicle in an effort to erode his morale. After several hours, in a last-ditch effort to persuade Essex to surrender, Giarrusso ordered a black police officer to communicate with Essex via a battery-operated bullhorn. This officer attempted to persuade Essex to surrender for several minutes, ending his efforts by saying: "What do you say, brother? Why not save yourself? Give up before it's too late. If you're wounded, we can get you medical help." In response, Essex screamed, "Power to the people!"[61]

Although this intermediary officer responded to this gesture by saying "Come on down, man. Don't die. Don't make us kill you", Essex refused to speak any other words.[61]

Shortly before 9 p.m., after almost seven hours crouched in the cubicle,[61] Essex suddenly charged into the open with his rifle at waist height and his right fist aloft, shouting "Come and get me!" before being almost immediately shot by police sharpshooters positioned on the roofs of adjacent buildings. The military helicopter, which had just approached to begin a further strafe operation, also fired scores of rounds into Essex's body. The momentum of the bullets propelled his body vertically several feet before Essex fell on his back approximately twenty feet from the cubicle, having failed to kill or wound any further officers in this final act. The barrage of gunfire would continue for almost four minutes. An autopsy later revealed Essex had received more than 200 gunshot wounds.[42]

An examination of Essex's rifle revealed he had only two remaining bullets at the time of his dash from the cubicle, indicating his final act may have been a symbolic suicide.[62]

In part due to conflicting reports as to the possibility of a further sniper or snipers,[63] twenty-eight hours would elapse between the beginning of Essex's siege at the hotel and police determining no further assailants remained at the scene.[64] Ballistic tests upon Essex's rifle would determine his weapon was the same as that used in the December 31 NOPD central lockup and Burkart Manufacturing Building shootings.[65]

Funeral[edit]

Days after Essex's death, his body was returned to his family in Kansas.[66] His funeral was held at the St. James Church in Emporia on 13 January.[67] His family authorized two wreaths to be placed upon his coffin. One wreath simply bore his childhood name: "Jimmy".[68] The second wreath bore the slogan "Power to the People".[69]

Shortly before Essex's funeral, Essex's family granted an interview to the media in which they stated the seeds of Essex's rage lay in the discrimination he had endured while serving in the Navy, whom they accused of ultimately causing the radicalization in their son and brother.[70] Furthermore, his mother stated that, although the family had been aware of extreme radical changes in Essex's attitude towards white people following his experiences in the Navy, they had not been aware of his plans, although his actions revealed he had viewed himself as something of a martyr for his cause.[71] According to his younger sister, Penny Fox: "He didn't want to see kids grow up to be oppressed by the white man. He really believed in the Black Power Revolution. He wanted to change it himself now, not wait another five hundred years."[72]

Victims[edit]

In both incidents, Essex shot a total of 21 people, nine of whom died. Two patrolmen were also hospitalized due to smoke inhalation received prior to and during their climbing down an elevator shaft to escape from a smoke-filled elevator stranded close to the 18th floor of the hotel. Seven other officers were slightly injured in crossfire in the final standoff with Essex.[73]

In total, ten of those shot in both incidents were policemen, five of whom died. All but one of those shot were Caucasian or Hispanic.

Killed[edit]

December 31, 1972, shootings:

- Police cadet Alfred Harrell (19). Gunshot wound to chest

- Officer Edwin Hosli Sr.* (30). Gunshot wound to chest and stomach

January 7, 1973, shootings:

|

|

Wounded[edit]

December 31, 1972, shootings:

- Lieutenant Horace Pérez (38). Ricochet wound to ankle

January 7, 1973, shootings:

|

|

Footnote

- The manager of the Downtown Howard Johnson's Hotel, Walter Collins, died of his injuries on January 26, 1973. Officer Edwin Hosli died of his injury on March 5, 1973.

"He was a man terribly frustrated and decided to fight. Most blacks deal with frustration in other ways ... if we are violent, we've been brainwashed to the point where we channel our violence against one another. It was different with Essex."

New Orleans civil rights activist Larry Jones, reflecting on the motivation behind Mark Essex's killings. February 1973.[69]

Aftermath[edit]

Two days after Essex's death, police visited the two-room apartment in which he had resided in the two months prior to his death. Officers discovered Essex had painted across all windows to the apartment and further covered the windows with bedding in order that no natural light could penetrate into the apartment. The sole source of light into both rooms was provided by a single red bulb, and the sole remaining furniture was a single waterbed. A map of New Orleans with a large circle drawn around the police headquarters and the Howard Johnson's Hotel was found on the floor. The walls of both rooms were covered in bold red and black lettering depicting racial and revolutionary slogans in both the English and several Bantu languages. Other slogans simply listed beasts from African folklore. Beneath one rallying slogan, Essex had painted the words: "My destiny lies in the bloody death of racist pigs."[69] Another inscription read: "The Third World – Kill Pig Nixon and his Running Dogs."[74]

In the weeks following Essex's massacre, several prominent individuals within New Orleans' Black community were interviewed with regards to the underlying motives behind his murders. Louisiana State Representative Louis Charbonnet would later reflect that the general media questioning of New Orleans' Black community made several individuals feel people "wanted to hear the black community of New Orleans apologize for [Essex's actions]." Charbonnet elaborated: "Here was a boy from Kansas who came here and vented his frustration in a suicide mission. What could I say about him? The black community in New Orleans did not invite him here; nor did we send him up to that rooftop."[75]

Several months after Essex's death, an eminent sociologist would state Essex's idyllic upbringing in Emporia—a community which had prided itself in a long history of racial harmony—had left Essex ill-prepared to encounter intolerance and continuous racial discrimination as a young adult as he had not been "vaccinated" against the harsh realities of bigotry as a youngster.[76]

One of the police officers killed in Essex's attack at the Downtown Howard Johnson's Hotel, Deputy Superintendent Louis Sirgo, had previously and publicly proclaimed that the most effective way to eliminate extremism within New Orleans was to end the social conditions that nourished social discontent within the Black community. Just months prior to his death, Sirgo had described the mistreatment of Black people in the city and nationwide as "the greatest sin of American society."[77]

For decades after her husband's death, Sirgo's wife, Joyce, annually presented the Louis Sirgo Memorial Award to the most promising recruit of the NOPD academy, selected by his or her fellow recruits.[41][78]

The Downtown Howard Johnson's Hotel is now a Holiday Inn hotel.[41]

Media[edit]

Literature[edit]

- Cawthorne, Nigel; Tibballs, Geoff (1993). Killers: Contract Killers, Spree Killers, Sex Killers. The Ruthless Exponents of Murder, the Most Evil Crime of All. London: Boxtree. pp. 238–242. ISBN 0-7522-0850-0.

- Foreman, Laura (1992). Mass Murderers: True Crime. New York: Time-Life Books. pp. 82-111. ISBN 0-7835-0004-1.

- Hernon, Peter (2005). A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper. New Orleans: Garrett County Press. ISBN 1-891053-48-5.

Television[edit]

- A 1982 documentary, The Killing of America, features a section devoted to the murders committed by Mark Essex.[79]

See also[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ The name Mata originates from the Swahili word for a hunter's bow.[3]

- ^ Although Essex did not inform his parents of his intentions to actually relocate to New Orleans, he had once informed them of his belief he could live "like a black man" in this city.[25]

- ^ The decision to form the Felony Action Squad sourced from a wave of homicides in New Orleans. In the eight months prior to September 1972, the city had seen 142 homicides—many involving wealthy businessmen killed in the course of robberies.[3]

- ^ Harrell's wife, Angie, later committed suicide due to the loss of her husband.[41]

- ^ To accommodate the superstitious, the Downtown Howard Johnson's Hotel did not have a 13th floor.

- ^ This number would increase to over 600 by the late evening of January 7.

- ^ Times-Picayune press photographer G.E. Arnold captured an iconic photograph of Coleman dying of a head wound in Duncan Plaza as fellow officer Leo Newman attempted to detect his pulse. Arnold also captured an image of a wounded Kenneth Solis—shot in the shoulder and with an exit wound beneath his rib cage—leaning against a tree as his colleague David McCann utilized medical training to treat his wound.

- ^ Unknown to Sirgo, Burl and Childress—suffering the early effects of smoke inhalation—had escaped from the elevator and scaled down the greased cables, although Burl had sustained minor hand and back injuries in a fall midway down the shaft.

- ^ As several sections of the hotel were ablaze at this point, the view of all parties firing in these exchanges was somewhat obscured.

References[edit]

- ^ "Officer Down Memorial Page: Sergeant Edwin C. Hosli Sr". odmp.org. November 21, 1999. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Mass Murderers, ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 87

- ^ a b c d e f Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 88

- ^ Moore, Leonard Nathaniel: Black rage in New Orleans - Police Brutality and African American Activism from World War II to Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana State University Press (Baton Rouge), 2010; ISBN 978-0-807-13590-7.

- ^ a b "'73 Shootings Still Haunt New Orleans". The Chicago Tribune. January 5, 2003. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Mass Murderers: True Crime ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 84

- ^ ""He Wanted to be a Man"". The Atlanta Voice. January 20, 1973. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 43

- ^ "Sniper Is Remembered as Quiet Youth Who Grew to Hate Whites in the Navy". The New York Times. January 10, 1973. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 pp. 84-85

- ^ "Lessons from Mark Essex and Christopher Dorner". Seattle Medium. March 2, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 14

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 26

- ^ Cawthorne, Nigel; Tibballs, Geoff. Killers: Contract Killers, Spree Killers, Sex Killers, the Ruthless Exponents of Murder, the Most Evil Crime of All. London: Boxtree, 1994, pp. 238-40; retrieved May 9, 2017; ISBN 0-7522-0850-0.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 15

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 pp. 16-17

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 8

- ^ Hunting Humans: The Rise of the Modern Multiple Murderer ISBN 978-0-140-11687-8 p. 258

- ^ "Crime Magazine: Mark Essex". Crime Magazine. July 11, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 86

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "1973: Mark Essex, the Howard Johnson's Sniper". The Times-Picayune. December 16, 2011. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 70

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 71

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 82

- ^ a b A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 76

- ^ "Dallas Police Shootings Revive Memory of Sniper Mark Essex, who Killed Nine New Orleanians, Including Five Cops, in 1973". The Advocate. July 8, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 80

- ^ a b Vargas, Ramon Antonio (July 8, 2016). "Dallas Police Shootings Revive Memory of Sniper Mark Essex, who Killed Nine New Orleanians, Including Five Cops, in 1973". nola.com. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 262

- ^ a b c Significant Tactical Police Cases: Learning from Past Events to Improve Upon Future Responses ISBN 978-0-398-08126-3 p. 63

- ^ Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers: Why They Kill ISBN 978-0-275-98475-5 p. 106

- ^ "Police Will 'Shoot to Kill'". The New York Times. September 19, 1972. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 pp. 81-82

- ^ McCoy, Lauren (January 9, 2023). "50 Years Since Hotel Sniper Mark Essex Terrorized Downtown New Orleans in 1973". Fox 8. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Mass Murderers: True Crime ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 88

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 92

- ^ a b "New Orleans 1973: Textbook Example of How Not to Stop a Serial Sniper". Arizona Daily Sun. January 4, 2003. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Significant Tactical Police Cases: Learning from Past Events to Improve Upon Future Responses ISBN 978-0-398-08126-3 p. 64

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 11

- ^ a b c d "Remember Howard Johnson's". myneworleans.com. March 10, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 pp. 89-102

- ^ "Dead Gunman Identified". Intelligencer Journal. January 10, 1973. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 91

- ^ Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 pp. 90-91

- ^ Significant Tactical Police Cases: Learning from Past Events to Improve Upon Future Responses ISBN 978-0-398-08126-3 p. 65

- ^ "Text of Police Report On N.O. Sniper Probe". The Town Talk. February 21, 1973. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ "Mark Essex, the Howard Johnson Sniper: Tracking a Killer". Crime Library. p. 6. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Details of New Orleans Shootout Emerge, but Two Crucial Questions Remain". The New York Times. January 15, 1973. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Doctor on Vacation was Slain with Wife". The New York Times. January 9, 1973. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ "Young Doc and Wife Were Slain". New York Daily News. January 9, 1973. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ "Helicopter Gunship Kills Sniper on Roof: Six Die in Hotel Siege". The Canberra Times. January 9, 1973. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 176

- ^ "Sniper May Have Planned More Attacks". The Monroe News-Star. January 16, 1973. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 127

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 151

- ^ a b Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 96

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 147

- ^ "Officer Down Memorial Page: Deputy Superintendent Louis Joseph Sirgo". odmp.org. November 21, 1999. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "New Orleans: Sniper Question Unanswered". The Canberra Times. January 15, 1973. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 101

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Mass Murder ISBN 0-747-20897-2 p. 101

- ^ "Sniper's Rifle Used in Other Attacks on Police". The Canberra Times. January 11, 1973. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ "Sniper Named". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. January 11, 1973. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ "Cite "Evidence of Conspiracy" in New Orleans Sniper Deaths". The Indiana Gazette. January 10, 1973. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ "Sniper Chase Still On". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. Australian Associated Press. January 12, 1973. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ "New Orleans Sniper Mark Essex Buried". The Pantagraph. United Press International. January 14, 1973. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ "N. Orleans Sniper Buried". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. January 15, 1973. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 110

- ^ "Sniper Chase Still On". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. January 12, 1973. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ "Race Riots Tear at U.S. Navy". The Canberra Times. February 6, 1973. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Jet: Volume 43. Johnson Publishing Company. February 2, 1973. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 98

- ^ The New Orleans Sniper: A Phenomenal Case Study of Constituting The Other ISBN 978-0-761-85389-3 p. 43

- ^ A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper ISBN 1-891053-48-5 p. 266

- ^ Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 84

- ^ Mass Murderers ISBN 0-7835-0004-1 p. 98

- ^ "New Orleans Police Department: Recruit Class #169 to Graduate NOPD Academy". nola.gov. November 21, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Killing of America". Youtube.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

Cited works and further reading[edit]

- Cawthorne, Nigel; Tibballs, Geoff (1993). Killers: Contract Killers, Spree Killers, Sex Killers. The Ruthless Exponents of Murder, the Most Evil Crime of All. London: Boxtree. ISBN 0-7522-0850-0.

- Duwe, Grant (2014). Mass Murder in the United States: A History. North Carolina: McFarland Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-786-43150-2.

- Hernon, Peter (2005). A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper. New Orleans: Garrett County Press. ISBN 1-891053-48-5.

- Foreman, Laura (1992). Mass Murderers: True Crime. New York: Time-Life Books. pp. 82–111. ISBN 0-7835-0004-1.

- Lane, Brian; Gregg, Wilfred (1994). The Encyclopedia of Mass Murder. London: Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 0-747-20897-2.

- Leyton, Elliot (2011) [1986]. Hunting Humans: The Rise of the Modern Multiple Murderer. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-140-11687-8.

- Marshall, Joseph; Wheeler, Lonnie (2004) [2000]. Street Soldier: One Man's Struggle to Save a Generation, One Life at a Time. New York: VisionLines Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-970-35130-2.

- Mijares, Tomas J.; McCarthy, Ronald M. (2015). Significant Tactical Police Cases: Learning from Past Events to Improve Upon Future Responses. Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publishing. ISBN 978-0-398-08126-3.

- Moore, Leonard (2021). Black Rage in New Orleans: Police Brutality and African American Activism from World War II to Hurricane Katrina. Baton Rouge: LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-807-17737-2.

- Ramsland, Katherine M. (2005). Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers: Why They Kill. Connecticut: Praeger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-275-98475-5.

- Waksler, Frances (2010). The New Orleans Sniper: A Phenomenal Case Study of Constituting The Other. Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-761-85389-3.

External links[edit]

- January 11, 1973 New York Times article focusing upon Mark Essex

- Contemporary news article pertaining to the fallout from the murders committed by Mark Essex

- February 1973 Jet magazine article focusing upon Mark Essex

- Image gallery pertaining to the siege at the Downtown Howard Johnson's

- Crimelibrary.com article upon Mark Essex

- Official report into the Downtown Howard Johnson's shootings

- 1949 births

- 1973 deaths

- 1972 mass shootings in the United States

- 1972 murders in the United States

- 1973 mass shootings in the United States

- 1973 murders in the United States

- 20th-century African-American people

- 20th-century American criminals

- African-American United States Navy personnel

- African Americans shot dead by law enforcement officers in the United States

- American criminal snipers

- American male criminals

- American mass murderers

- Anti-police violence in the United States

- Attacks during the New Year celebrations

- Burials in Kansas

- Crimes in New Orleans

- Criminals from Kansas

- Deaths by firearm in Louisiana

- Male murderers

- Mass murder in 1973

- Mass murder in Louisiana

- Mass murder in the United States

- Mass shootings in the United States

- People from Emporia, Kansas

- Racially motivated violence against white Americans

- Racially motivated violence in the United States

- United States Navy sailors