Raven banner

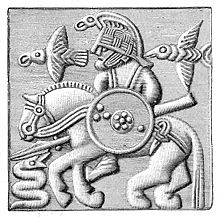

The raven banner (Old Norse: hrafnsmerki [ˈhrɑvnsˌmerke]; Middle English: hravenlandeye) was a flag, possibly totemic in nature, flown by various Viking chieftains and other Scandinavian rulers during the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries. Period description simply describes it as a war banner with a raven mark on it, although no complete visual description or depiction of the raven banner is known from the time. Norse and European period artwork, however, depicts war banners as roughly triangular, with a rounded outside edge on which there hung a series of tabs or tassels, some with a resemblance to ornately carved "weather-vanes" used aboard Viking longships, indicating that some raven banners may have been constructed in a similar manner.

Scholars conjecture that the raven flag was a symbol of Odin, who was often depicted accompanied by two ravens named Huginn and Muninn. Its intent may have been to strike fear in one's enemies by invoking the power of Odin. As one scholar notes regarding encounters between the Christian Anglo-Saxons and the invading pagan Scandinavians:

The Anglo-Saxons probably thought that the banners were imbued with the evil powers of pagan idols, since the Anglo-Saxons were aware of the significance of Óðinn and his ravens in Norse mythology.[1]

Raven symbolism in Norse culture[edit]

The raven is a common iconic figure in Norse mythology. The highest god Odin had two ravens named Huginn and Muninn ("thought" and "memory" respectively) who flew around the world bringing back tidings to their master. Therefore, one of Odin's many names was the "raven god" (Hrafnaguð). In Gylfaginning (c. 1220), the medieval Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson explains:

|

Hrafnar tveir sitja á öxlum honum ok segja í eyru honum öll tíðendi, þau er þeir sjá eða heyra. Þeir heita svá, Huginn ok Muninn. Þá sendir hann í dagan at fljúga um heim allan, ok koma þeir aftr at dögurðarmáli. Þar af verðr hann margra tíðenda víss. Því kalla menn hann Hrafnaguð, svá sem sagt er:

|

Two ravens sit on Odin's shoulders, and bring to his ears all that they hear and see. Their names are Huginn and Muninn. At dawn he sends them out to fly over the whole world, and they come back at breakfast time. Thus he gets information about many things, and hence he is called Rafnagud (raven-god). As is here said:

|

Odin was also closely linked to ravens because in Norse myths he received the fallen warriors at Valhalla, and ravens were linked with death and war due to their predilection for carrion. It is consequently likely that they were regarded as manifestations of the Valkyries, goddesses who chose the valiant dead for military service in Valhalla.[4] A further connection between ravens and Valkyries was indicated in the shapeshifting abilities of goddesses and Valkyries, who could appear in the form of birds.[5]

The raven appears in almost every skaldic poem describing warfare.[6] To make war was to feed and please the raven (hrafna seðja, hrafna gleðja).[6] An example of this is found in Norna-Gests þáttr, where Regin recites the following poem after Sigurd kills the sons of Hunding:

Nú er blóðugr örn |

Now the blood eagle |

Above all, kennings used in Norse poetry identify the raven as the bird of blood, corpses and battle;[9] he is the gull of the wave of the heap of corpses, who screams dashed with hail and craves morning steak as he arrives at the sea of corpses (Hlakkar hagli stokkin már valkastar báru, krefr morginbráðar er kemr at hræs sævi).[10]

In black flocks, the ravens hover over the corpses and the skald asks where they are heading (Hvert stefni þér hrafnar hart með flokk hinn svarta).[11] The raven goes forth in the blood of those fallen in battle (Ód hrafn í valblóði).[12] He flies from the field of battle with blood on his beak, human flesh in his talons and the reek of corpses from his mouth (Með dreyrgu nefi, hold loðir í klóum en hræs þefr ór munni).[13] The ravens who were the messengers of the highest god, Huginn and Muninn, increasingly had hellish connotations, and as early as in the Christian Sólarljóð, stanza 67, the ravens of Hel(l) (heljar hrafnar) who tear the eyes off backtalkers are mentioned.[9] Two curses in the Poetic Edda say "may ravens tear your heart asunder" (Þit skyli hjarta rafnar slíta).[14] and "the ravens shall tear out your eyes in the high gallows" (Hrafnar skulu þér á hám galga slíta sjónir ór).[15] Ravens are thus seen as instruments of divine (if harsh and unpleasant) justice.

Despite the violent imagery associated with them, early Scandinavians regarded the raven as a largely positive figure; battle and harsh justice were viewed favorably in Norse culture.[16] Many Old Norse personal names referred to the raven, such as Hrafn,[17] Hrafnkel[18] and Hrafnhild.[19]

Usage[edit]

Late 9th century[edit]

The raven banner was used by a number of Viking warlords regarded in Norse tradition as the sons of Ragnar Lodbrok. The first mention of a Viking force carrying a raven banner is in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. For the year 878, the Chronicle relates:

In the winter of the same year, the brother of Ivar and Halfdan landed in Devonshire, Wessex, with 23 ships, and he was killed there along with 800 other people and 40 of his soldiers. The war banner (guþfana) which they called "Raven" was also taken.

The 12th-century Annals of St Neots claims that a raven banner was present with the Great Heathen Army and adds insight into its seiðr- (witchcraft-) influenced creation and totemic and oracular nature:

|

Dicunt enim quod tres sorores Hynguari et Hubbe, filie uidelicet Lodebrochi, illud uexillum tex'u'erunt et totum parauerunt illud uno meridiano tempore. Dicunt etiam quod, in omni bello ubi praecederet idem signum, si uictoriam adepturi essent, appareret in medio signi quasi coruus uiuus uolitans; si uero uincendi in futuro fuissent, penderet directe nichil mouens – et hoc sepe probatum est[20] |

It is said that three sisters of Hingwar and Habba [Ivar and Ubbe], i.e., the daughters of Ragnar Loðbrok, had woven that banner and gotten it ready during one single midday's time. Further it is said that if they were going to win a battle in which they followed that signum, there was to be seen, in the center of the signum, a raven, gaily flapping its wings. But if they were going to be defeated, the raven dropped motionless. And this always proved true.[21][22] |

Geffrei Gaimar's Estorie des Engles (written around 1140) mentions the Hrafnsmerki being borne by the army of Ubbe at the Battle of Cynwit (878): "[t]he Raven was Ubbe's banner (gumfanun). He was the brother of Iware; he was buried by the vikings in a very big mound in Devonshire, called Ubbelawe."[23]

10th century[edit]

In the 10th century, the raven banner seems to have been adopted by Norse-Gaelic kings of Dublin and Northumbria. Many of the Norse-Gaelic dynasts in Britain and Ireland were of the Uí Ímair clan, which claimed descent from Ragnar Lodbrok through his son Ivar.

A triangular banner appearing to depict a tilted cross (possibly a bird) appears on a penny minted by Olaf Cuaran around 940. The coin features a roughly right isosceles triangular standard, with the two equilateral sides situated at the top and staff, respectively. Along the hypotenuse are a series of five tabs or tassels. The staff is topped by what appears to be a cross; this may indicate a fusion of pagan and Christian symbolism.[24]

- Pennies of Olaf Cuaran (minted ca. 940)

The raven banner was also a standard used by the Norse Jarls of Orkney. According to the Orkneyinga Saga, it was made for Sigurd the Stout by his mother, a völva or shamanic seeress. She told him that the banner would "bring victory to the man it's carried before, but death to the one who carries it." The saga describes the flag as "a finely made banner, very cleverly embroidered with the figure of a raven, and when the banner fluttered in the breeze, the raven seemed to be flying ahead." Sigurd's mother's prediction came true when, according to the sagas, all of the bearers of the standard met untimely ends.[26] The "curse" of the banner ultimately fell on Jarl Sigurd himself at the Battle of Clontarf:

Earl Sigurd had a hard battle against Kerthialfad, and Kerthialfad came on so fast that he laid low all who were in the front rank, and he broke the array of Earl Sigurd right up to his banner, and slew the banner-bearer. Then he got another man to bear the banner, and there was again a hard fight. Kerthialfad smote this man too his death blow at once, and so on one after the other all who stood near him. Then Earl Sigurd called on Thorstein the son of Hall of Sida, to bear the banner, and Thorstein was just about to lift the banner, but then Asmund the White said, "Don't bear the banner! For all they who bear it get their death." "Hrafn the Red!" called out Earl Sigurd, "bear thou the banner." "Bear thine own devil thyself," answered Hrafn. Then the earl said, "`Tis fittest that the beggar should bear the bag;'" and with that he took the banner from the staff and put it under his cloak. A little after Asmund the White was slain, and then the earl was pierced through with a spear.[27]

Early 11th century[edit]

The army of King Cnut the Great of England, Norway and Denmark bore a raven banner made from white silk at the Battle of Ashingdon in 1016. The Encomium Emmae reports that Cnut had

a banner which gave a wonderful omen. I am well aware that this may seem incredible to the reader, but nevertheless I insert it in my veracious work because it is true: This banner was woven of the cleanest and whitest silk and no picture of any figures was found on it. In case of war, however, a raven was always to be seen, as if it were woven into it. If the Danes were going to win the battle, the raven appeared, beak wide open, flapping its wings and restless on its feet. If they were going to be defeated, the raven did not stir at all, and its limbs hung motionless.[28]

The Lives of Waltheof and his Father Sivard Digri (The Stout), the Earl of Northumberland, written by a monk of Crowland Abbey (possibly the English historian William of Ramsey), reports that the Danish jarl of Northumbria, Sigurd, was given a banner by an unidentified old sage. The banner was called Ravenlandeye.[29]

According to the Heimskringla, Harald Hardrada had a standard called Landøyðan or "Land-waster." This is often assumed to be a raven banner based on the similarity of its name to Sigurd of Northumbria's "Ravenlandeye," though there is no direct evidence connecting Harald's standard with ravens. In a conversation between Harald and King Sweyn II of Denmark,

Sveinn asked Haraldr which of his possessions of his he valued most highly. He answered that it was his banner (merki), Landøyðan. Thereupon Sveinn asked what virtue it had to be accounted so valuable. Haraldr replied that it was prophesied that victory would be his before whom this banner was borne; and added that this had been the case ever since he had obtained it. Thereupon Sveinn said, "I shall believe that your flag has this virtue if you fight three battles with King Magnús, your kinsman, and are victorious in all."[30]

Years later, during Harald's invasion of England, Harald fought a pitched battle against two English earls outside York. Harald's Saga relates that

when King Haraldr saw that the battle array of the English had come down along the ditch right opposite them, he had the trumpets blown and sharply urged his men to the attack, raising his banner called Landøyðan. And there so strong an attack was made by him that nothing held against it.[31]

Harald's army flew the banner at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, where it was carried by a warrior named Frírek. After Harald was struck by an arrow and killed, his army fought fiercely for possession of the banner, and some of them went berserk in their frenzy to secure the flag. In the end the "magic" of the banner failed, and the bulk of the Norwegian army was slaughtered, with only a few escaping to their ships.[32]

Other than the dragon banner of Olaf II of Norway, the Landøyðan of Harald Hardrada is the only early Norwegian royal standard described by Snorri Sturluson in the Heimskringla.[33]

In two panels of the famous Bayeux tapestry, standards are shown which appear to potentially be raven banners (although one is small and not given a motif). The Bayeux tapestry was commissioned by Bishop Odo, the half-brother of William the Conqueror; as one of the combatants at the Battle of Hastings, Odo would have been familiar with the standards carried into the fight. In one of the panels, depicting a Norman cavalry charge against an English shield-wall, a charging Norman knight is depicted with a semicircular banner emblazoned with a standing black bird. In a second, depicting the deaths of Harold Godwinson's brothers, a triangular banner closely resembling that shown on Olaf Cuaran's coin lies broken on the ground. Scholars are divided as to whether these are simply relics of the Normans' Scandinavian heritage (or for that matter, the Scandinavian influence in Anglo-Saxon England) or whether they reflect an undocumented Norse presence in either the Norman or English army.[34]

Modern reception[edit]

There is no indication that the raven banner was ever carried as a universal flag of Scandinavians.[35]

In modern times the Danish Guard Hussar Regiment (est. 1762) seemingly used a raven banner as their coat of arms, perhaps an allusion to the Viking warriors.

The raven symbol is still in use by the regiment's 1st Battalion 1st Armoured infantry company, in the sleeve badge worn on the left sleeve.[36]

From the foundation of the collaborationist Nasjonal Samling party in Norway in 1933 until the end of World War 2, the party's paramilitary group and youth organisation, the Hirden and Unghirden, carried raven banners as military unit flags. [37] Symbols and iconography from the viking age was celebrated and appropriated by the Nasjonal Samling party for nationalistic reasons.

The coat of arms of the Norwegian Intelligence Service features two ravens representing Huginn and Muninn, the ravens providing the god Odin with information.[38][39]

The coat of arms of Shetland depicts a longship with a raven on the sail and an alternative form of the banner (black raven on a rectangular, red field) is used as the symbol of Up Helly Aa, a festival that celebrates the Islands' Norse heritage. The coat of arms of the Isle of Man, a formerly Norse-dominated kingdom, also features a raven, but as a supporter on the right.

The Eastern Counties RFU adopted the raven as its badge in 1926. It was chosen as representing the heritage of the constituent counties – then Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex; now Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire – as part of the Danelaw.[40]

-

Shoulder sleeve insignia of the Danish Guard Hussar Regiment's 1st Battalion 1st Armoured infantry company

-

Raven banner used by Hirden in Norway.

-

Coat of arms of the Norwegian Intelligence Service with Odins ravens Huginn and Muninn

-

Raven banner at Shetlands Norse heritage festival Up Helly Aa

-

Coat of arms of the Isle of Man, a formerly Norse-dominated kingdom, with a raven as the right supporter

See also[edit]

- Cultural depictions of ravens

- Fairy flag

- Hrafnsmál

- Jagdstaffel 18, which used a black raven insignia

- Uí Ímair

- Valravn

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hrafnhildur Bodvarsdottir (1976) p. 112.

- ^ Gylfaginning at «Norrøne Tekster og Kvad» Archived 2007-05-08 at the National and University Library of Iceland, Norway.

- ^ "Rasmus B. Anderson's translation at the Northvegr foundation".

- ^ "Viking Answer Lady Webpage - Valkyries, Wish-Maidens, and Swan-Maids". www.vikinganswerlady.com.

- ^ Examples of this occur in Þrymskviða, stanzas 3 and 4, when Freya lends her bird fetch to Loki; and in the Valkyrie Kára of whom an account survives in Hrómundar saga Gripssonar.

- ^ a b Hjelmquist 142.

- ^ "Norna-Gests þáttur". www.snerpa.is.

- ^ "Hardman § 6". Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ a b Hjelmquist 143.

- ^ Hjelmquist citing Fornmanna sögur III p. 148, in Hjelmquist 143.

- ^ In a poem by Þórðr in Bjarnar Saga Hitdælakappa, p. 67, cited in Hjelmquist 143.

- ^ Stanza 2, in Krákumál, cited in Hjelmquist 143.

- ^ Stanza 2 and 3, in Haraldskvæði, cited in Hjelmquist 143.

- ^ in stanza 8 of Guðrúnarkviða II cited in Hjelmquist 144.

- ^ In stanza 45 in Fjölsvinnsmál cited in Hjelmquist 144.

- ^ E.g., Woolf 63–81; Poole passim.

- ^ E.g., Gunnlaugs saga passim; Reykdæla saga ok Víga-Skútu §13.

- ^ E.g., Hrafnkels saga passim.

- ^ E.g., Ketils saga hœngs § 3.

- ^ Annals of St Neots (878), ed. Dumville and Lapidge, p. 78.

- ^ Lukman 141

- ^ Cf. Grimm's earlier edition and translation: [V]exillum quod reafan vocant. Dicunt enim quod tres sorores Hungari et Habbae, filiae videlicet Lodebrochi illud vexillum texuerunt, et totum paraverunt illud uno meridiano tempore. Dicunt etiam quod in omni bello, ubi praecederet idem signum, si victoriam adepturi essent, appareret in medio signi quasi corvus vivus volitans; sin vero vincendi in futuro fuissent, penderet directe nihil movens: et hoc saepe probatum est. "The daughters of Loðbrók had woven that banner and finished it during one single midday's time. It also is said that in any battle where the signum was borne before them, if they were to win victory one would see in the middle of the signum a living raven flying; but if they were about to be defeated, it hung straight and still." Grimm ch. 35

- ^ Lukman, 141–142.

- ^ a b c Barraclough, E.M.C. (1971). Flags of the World. Great Britain: William Cloves & Sons Ltd. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0723213380.

- ^ Herbert Appold Grueber, Handbook of the coins of Great Britain and Ireland in the British Museum. London/Oxford: British Museum. Dept. of Coins and Medals & the Clarendon Press, 1899, p. 20 (no. 117).

- ^ Orkneyinga Saga § 11.

- ^ Njal's Saga §156.

- ^ Trætteberg 549–555.

- ^ Lukman 148. The Crowland author comments on the name of the banner, "quod interpretatur corvus terrae terror," "which means Raven, terror of the land."

- ^ Haralds saga Sigurðarsonar § 22.

- ^ Haralds saga Sigurðarsonar § 85.

- ^ Haralds saga Sigurðarsonar § 88.

- ^ Cappelen 34–37.

- ^ Barraclough passim. It should, of course, be noted that by 1066, all of the armies involved in hostilities in the British Isles, Norwegian, English and Norman, were at least nominally Christian. The Normans were in many ways, including linguistically, quite far removed from their Norse origins.

- ^ Engene 1–2; see also Barraclough passim.

- ^ "Sleeve Insignia GHR". arma-dania.dk (in Danish). Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Sæther, Orvar (1941). Hirdboken: hirdens historie og oppgaver [The Hird book: The hirds history and tasks] (in Norwegian Bokmål). Norway: Nasjonal Samlings Rikstrykkeri.

- ^ Norwegian Intelligence Service website, in Norwegian

- ^ Egeberg, Kristoffer (10 September 2008). "Mange vil bli spion". Dagbladet. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "About Us – History – The ECRU Raven". www.ecrurugby.com.

References[edit]

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. (English translation). Everymans Library, 1991.

- Barraclough, Captain E.M.C. "The Raven Flag". Flag Bulletin. Vol. X, No. 2–3. Winchester, MA: The Flag Research Center (FRC), 1969.

- Cappelen, Hans. "Litt heraldikk hos Snorre." Heraldisk tidsskrift No. 51, 1985 p. 34–37. Also printed in Icelandic as "Heimskringla og skjaldarmerkin", Morgunbladir, Reykjavik 3.11.1985

- Dumville, David and Michael Lapidge, eds. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Vol 17: The Annals of St. Neots with Vita Prima Sancti Neoti. Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer. 1985.

- Engene, Jan Oskar. "The Raven Banner and America." NAVA News, Vol. XXIX, No. 5, 1996, pp. 1–2.

- Forte, Angelo, Richard Oram and Frederik Pedersen. Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-521-82992-5.

- Grimm, Jakob. Teutonic Mythology. 4 vols. Trans. James Steven Stallybras. New York: Dover, 2004.

- Hjelmquist, Theodor. "Naturskildringarna i den norröna diktningen". In Hildebrand, Hans (ed). Antikvarisk tidskrift för Sverige, Vol 12. Ivar Hæggströms boktryckeri, Stockholm. 1891.

- Hrafnhildur Bodvarsdottir. The Function of the Beasts of Battle in Old English Poetry. PhD Dissertation, 1976, State University of New York at Stony Brook. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International. 1989.

- Lukman, N. "The Raven Banner and the Changing Ravens: A Viking Miracle from Carolingian Court Poetry to Saga and Arthurian Romance." Classica et Medievalia 19 (1958): pp. 133–51.

- Njal's Saga. Trans. George DaSent. London, 1861.

- Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. Trans. Pálsson, Hermann and Edwards, Paul (1978). London: Hogarth Press. ISBN 0-7012-0431-1. Republished 1981, Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044383-5.

- Poole, R. G. Viking Poems on War and Peace: A Study in Skaldic Narrative. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1991.

- Sturluson, Snorri. "King Harald's Saga." Heimskringla. Penguin Classics, 2005.

- Trætteberg, Hallvard. "Merke og Fløy." Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder, Vol. XI, Oslo, 1966, columns 549–555.

- Woolf, Rosemary. "The Ideal of Men Dying with their Lord in the Germania and in The Battle of Maldon." Anglo-Saxon England Vol. 5, 1976.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Raven banner at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Raven banner at Wikimedia Commons

- Viking Answer Lady on Viking flags

- Njal's Saga – Public domain edition of translated by George DaSent, 1861, at Northvegr.org

- The Raven Banner

![Banner Penny, obverse[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/York_banner_penny_%28frontside%29.jpg/281px-York_banner_penny_%28frontside%29.jpg)

![Banner Penny, reverse[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/York_banner_penny_%28backside%29.jpg/281px-York_banner_penny_%28backside%29.jpg)

![Raven Penny, obverse and reverse[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/York_raven_penny.jpg/447px-York_raven_penny.jpg)