Politics of the United Kingdom in the 19th century

The politics of the United Kingdom in the 19th century describes the parliamentary-cabinet system of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland,[a][1] shaped in the 19th century by constitutional conventions.

The United Kingdom is a parliamentary monarchy. In this country, there is no conventionally understood written constitution to this day, in other words: a formal constitution, as is the case in other countries. Instead of one document, there are a number of norms called constitutional conventions, or the constitution in a material sense. The doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty applies. The highest rank is held by statutes, which determine, among other things, the role of local government in society. In reality, the British government has freedom in shaping the structure and functioning of public administration bodies. The structure of local government was initiated by a series of statutes in the 19th century.[2]

Political reforms[edit]

Sources of constitutional law[edit]

The United Kingdom does not have a written constitution to this day. In the 19th century, sources of constitutional law in the United Kingdom included:

- Positive law, comprising fundamental legal acts such as the Magna Carta (1215), the Triennial Act (1641),[3] the Habeas Corpus Act (1679), the Bill of Rights (1689), and the Act of Settlement (1701);

- Case law, concerning judicial decisions and covering the most important issues of constitutional law;

- Constitutional conventions, also known as unwritten law norms, which emerged as a result of the actions of non-judicial institutions in matters of the state's organization;[4]

- Legal works, treaties, and legal textbooks.[2][4][5]

Legislative acts[edit]

The first law introducing significant political changes in the United Kingdom was the Reform Act passed on 4 June 1832, which aimed to expand political power to new social classes and establish new electoral districts (the reforms of Charles Grey).[6][7] It introduced democratic and elective municipal councils;[b][8] the second one, the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, reorganized the administration of poor relief. Rural parishes transferred care for the poorest to the supervision of newly created workhouses,[9] which alongside the police became the most important local government function at that time.[10] Another law, the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835, reformed municipal self-governance, stipulating that authority in individual regions should belong to elected councils.[6][11] This act allowed only men who paid municipal taxes for the benefit of the poor to vote for the new authorities.[12]

Between 1867 and 1885, the extension of voting rights for men was introduced, laying the groundwork for mass political democracy in the UK. Among other laws, the Ballot Act (1872), the Corrupt Practices Act (1883), and the Redistribution Act (1885) were issued.[13] Until 1894, several significant laws were introduced aimed at democratizing elections to local councils. This allowed for membership by election rather than the purchase of mandates. In 1894, the Local Government Act was passed, which divided counties into urban and rural districts.[14] Subsequently, additional acts were enacted to streamline the functioning of local government bodies.[10]

The United Kingdom evolved into a parliamentary monarchy with a parliamentary-cabinet system, often referred to as the mother of the parliamentary-cabinet system.[3][15]

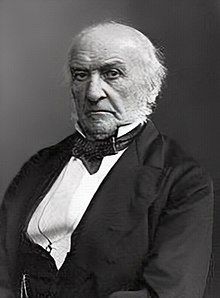

From Charles Grey's reforms to William Gladstone's[edit]

The electoral system existing since 1832 was undemocratic, even though the reform led to the participation and political activity of the middle class in the country.[16] The House of Commons consisted of two deputies from each county, elected through high property census-based elections. The second group in the House of Commons was composed of representatives of towns. Before the reform, the House had 658 members, with 122 representing counties, 432 representing urban districts, and the remaining four representing universities: Oxford and Cambridge.[17] In response to pressure from social groups and the labor movement in the 19th century, electoral reforms were undertaken, leading to the introduction of universal suffrage and the democratization of the House of Commons.

The reforms by Charles Grey in 1832 took representation away from small, rotten boroughs with up to 300,000 inhabitants and granted it to other larger towns. As a result, 56 electoral districts were abolished,[18] leaving one mandate in 20 of them. The 143 obtained mandates were distributed among counties and towns.[19]

The reform considered newly emerging industrial districts, which previously had no representation in parliament. It provided for 65 mandates for them.[20] The same number of seats was also given to rural districts, whose representatives were intended to counterbalance the bourgeoisie.[18] Additionally, the property census was lowered in counties and towns. Since 1832, 20% of English households had gained voting rights.[20] However, the property census still remained too high, excluding representatives of small craftsmen and merchants from voting. In rural areas, richer landowners gained voting rights after a slight reduction in the property census.[18] Catholics gained voting rights in 1829,[c][21] and Jews in 1858. Benjamin Disraeli's reform in 1867, who was a member of the third government of Edward Smith-Stanley, further lowered the property census (the number of voters increased to 2.5 million).[22] As a result of Disraeli's reform, workers began to constitute over half of the electorate.[23]

The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century led to a high development of mechanized industry and communication. The expansion of the colonial empire favored England's leading position in the global economy and politics. These differences brought about changes in the social structure: the number of the proletariat increased, and the significance of financial oligarchy grew, leading to further reforms that increased the number of voters.[24] In 1872, secret voting was introduced. William E. Gladstone's reform between 1884 and 1885 broke with the principle that the right to vote was a privilege of certain city corporations.[25] Counties adopted the democratic principle that this right was the subjective right of citizens. Single-member districts were introduced, except for 27 cities with populations ranging from 50 to 165 thousand, which became two-member districts.[26] The property census was significantly lowered, resulting in an increase in the number of voters to 40% of the total population.[27]

Fight for workers' voting rights[edit]

The significance of landlords and gentry diminished, and in the House of Lords, representatives of big capital were increasingly numerous. The burghers and workers' groups demanded democratic reforms. The labor movement known as Chartism emerged, advocating for political demands in defense of electoral rights. The first petition in 1837 called for full democratization of elections to the House of Commons. It was rejected by the House in 1839, and many striking workers were arrested.[11]

Chartists presented their program in the so-called Six Points of the People's Charter, the demands of which were implemented in 1867 and 1884 (granting electoral rights to social classes not included in the 1832 reform).[28] In 1840, they founded the National Charter Association, headquartered in Manchester. This organization had a bylaw and defined authorities. Proposals for Feargus E. O'Connor's agrarian plan, the leader of the movement, were rejected, and the association itself was dissolved in 1842.[29] After the decline of Chartism in the late 1840s, the labor movement took on a more economic character.[d] Trade unions, legally operating since 1871, became its form.[30]

In addition to the Chartist movement, other organizations operated: the Democratic Federation, the Fabian Society (1881), the dockers' union (1889), and the Independent Labour Party (1893).[e][31] These were unions representing masses of unskilled workers, which formed the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) in 1899. The main goal of the committee was to increase workers' representation in the British Parliament.[32]

Parliament[edit]

The Parliament in the United Kingdom (the legislative branch) consisted of three parts: the lower house of parliament called the House of Commons, the upper house called the House of Lords, and the monarch. The latter had the right to convene parliament for sessions, however, with the countersignature and upon the request of the Prime Minister.[3] At the same time, the sovereign was the one who opened and closed sessions, as parliament worked in sessional mode. Parliamentary work lasted throughout the week, usually from the afternoon until late at night. Saturday and Sunday were mainly reserved for meetings with constituents, and mornings during the week (except Friday) were for committee work and group meetings. Parliament was sovereign and all-powerful. It exercised control over the executive branch and had the exclusive right to enact all taxes and charges. Parliament decided on the issuance of dispensations and suspensions.[33][34]

Irish philosopher and politician Edmund Burke (18th century) expressed his views on the virtues and wonders of the English system in a metaphysical apostrophe:

...the well ordered structure of our Church and State, the sanctuary, the holy of holies of that ancient law, guarded by the power of reverence, the power of authority, both a temple and a fortress... this awe-inspiring structure should watch over and protect the land subject to it...[35]

— Edmund Burke, Letter to a Noble Lord 1796

Ruler[edit]

The ruler – king/queen or otherwise monarch – exercised their power based on hereditary principles. Their authority transformed into purely representational. Initially, all power belonged to the king, or to the king in parliament, or to the king in council. Judicial decisions made in the name of the king eventually shifted to parliament, the cabinet, and the judiciaries.[36] The maxim governing the character of the nineteenth-century British regime was: The King can do no wrong and The King reigns, but does not govern.[4] The monarch was also inviolable and irresponsible. He also served as the head of the Anglican Church and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. He could decide on war and peace. Laws could be issued in his name, which he could sanction. They had the right to summon and dissolve parliament[36] and present government plans.[37]

All real power resided in the hands of parliament, the cabinet, and the judiciaries. Cooperation between the king and the cabinet was facilitated through the prime minister. The Privy Council currently consists of 300 people. It included cabinet ministers and dignitaries. In the council, the king issued regulations, and ministers took parliamentary responsibility for them. Certain powers, known as royal prerogatives, remained with the monarch, but they were entirely representational and symbolic.[36]

Another general principle was the requirement for the signature (countersignature) of the relevant ministers (from 1 to 4) for decisions made by the monarch. The ruler was well informed about political events and parliamentary proceedings, as he regularly received reports on the work of this body and held weekly audiences with the head of government.[36]

House of Lords[edit]

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, consisted of hereditary and life peers (since 1876, non-hereditary law lords),[f] and lords spiritual. In the 19th century, the right to sit in the House was held by 400 secular peers of England,[18] lords spiritual (28 bishops and Anglican archbishops), 16 Scottish peers (since 1707), and 28 Irish peers (since 1801),[18] including five representatives of the royal family, the Dukes of Wales, Edinburgh, Gloucester, York, and Kent. Members of the upper house of the British Parliament held titles of nobility. The power to grant titles belonged to the king, who could choose from dignities such as earl, duke, marquess, or baron.[18]

Hereditary lords appointed from their circle those who would serve in functional roles (known as functional lords) and those who were non-functional. In the House of Lords, the title was hereditary, but it did not guarantee a seat. This house retained its aristocratic character. The Lord Chancellor presided over the House of Lords. The House of Lords was always conservative and retained the power of suspensive veto over bills. Regarding money bills, the House did not have the power of suspensive veto; it could only propose amendments. The House of Lords had limited legislative power and its judicial powers were also restricted, although it remained the highest court of appeal.[37]

House of Commons[edit]

The House of Commons consisted of an average of 658 members elected in general elections using the first-past-the-post voting system, in single-member electoral districts. The term of office could last a maximum of seven years (since 1716), regulated by the Septennial Act of 1715. This house emerged already in the 17th century. This was due to the fact that at the beginning of the 18th century, the Hanoverian dynasty ascended to the English throne. The king rarely resided in England and appointed the prime minister to manage the administration.[33] The leader stood at the head of the House of Commons, while the speaker presided over the proceedings.[3]

The principle of collective responsibility, known as a vote of no confidence (the first in the world), was introduced.[33] In 1809, Parliament passed a law prohibiting the sale of seats in the House of Commons, a practice that had been quite common until then to garner support for legislative projects.[38] However, there were certain restrictions on membership in the House of Commons, such as a ban on holding a mandate for civil servants, military personnel, and police officers. The House of Commons had two main political factions: the Tories (Conservative Party) and the Whigs (Liberal Party).[39] It served as a representative body, exercised legislative power, conducted oversight over public finances, and scrutinized the British government. It also decided on the shape of public legislative projects presented to the monarch.[37]

The seat of the British Parliament became the Palace of Westminster, a monumental building rebuilt in neo-Gothic style in 1834 after a fire destroyed the previous structure.[40][41]

Government and cabinet[edit]

In the governance system of the United Kingdom, there was a division of the executive power into three branches. The first was the government, composed of ministers appointed by the Prime Minister or by the monarch, who simultaneously represented the executive power. The Prime Minister assumed the position of the First Lord of the Treasury, while the functions of the Chancellor of the Exchequer represented the Treasury Minister. The next organ was the cabinet (a collegiate, proper governmental body), originating from the Privy Council (a political body much smaller in number than the government) that served as the proper center of power. The cabinet consisted of several ministers, including the Lord Chancellor, the Lord President of the Council, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Home Affairs, and War.[36]

The leader of the party that won the elections to the House of Commons was designated by the monarch to the position of Prime Minister, with the mission of forming the government.[36] The leader of the strongest opposition party obtained the position of Leader of the Opposition. Members of the opposition party formed their own government called the shadow cabinet (a concept developed by the Conservative Party).[42] Each minister in the legitimate government had their counterpart in the shadow cabinet. Thanks to this practice, the opposition party was prepared to potentially assume power.

The government, also known as the Servant of the Crown,[43] could hinder independent legislative initiatives, evade responsibility for political actions, avoid corrective actions and changes, and shape the legal order in the United Kingdom.[37] The government was divided into senior ministers (currently 100 members),[36] who directed the work of individual departments, and subordinate junior ministers (from 40 to 60 members), whose main task was to ensure communication between the government and the House of Commons. The government as a whole bore collective political responsibility before the Houses.[36]

Judiciary[edit]

The structure of the English court system, established in the 12th century, remained in place until the second half of the 19th century. The House of Lords held the status of the highest appellate court and had the authority to judge lords and ministers. The Court of Common Pleas handled civil cases, the Court of King's Bench dealt with criminal cases, and the Court of Exchequer handled complaints against the crown in fiscal matters. A notable role was played by the Court of Chancery, which applied simplified procedures (beyond common law, but according to equity principles).[33]

In criminal and administrative matters, justices of the peace served as a judicial institution. From the 14th century onwards, eight justices of the peace were elected in each county. In the Middle Ages, the organization of crown courts (Courts of Assize) also emerged. Judges adjudicated criminal and civil cases in the field. The territory of England was divided into six judicial circuits, a division that was in place from the 14th to the second half of the 19th century. Additionally, "juries of the country" were chosen based on specified annual incomes from among landowners in each county to collaborate with justices of the peace and crown judges, forming what was known as the Grand Jury for civil or criminal cases. No qualifications were required for these appointed jurors. The legal system was dualistic, with judgments rendered in the name of the king based on common law or equity.[33]

From 1873 to 1875, all courts in the United Kingdom were consolidated into a single Supreme Court in London. The appellate function remained under the jurisdiction of the House of Lords. A separate Royal Courts of Justice was established in 1882 for England and Wales, which also became the seat of the Supreme Court. The distinctions between courts applying common law and those adjudicating on the basis of equity were abolished. At a lower level, county courts were established in 1846, while the justices of the peace continued their activities, overseen voluntarily by local notables.[44]

Distinctive procedural features of the English courts included:

- Lack of a separate Ministry of Justice

- A small professional judiciary

- Absence of a distinct representative in criminal proceedings

The Appellate Tribunal was the House of Lords. There was no institution of administrative courts in the British judiciary, a role still performed by county courts and justices of the peace.[44]

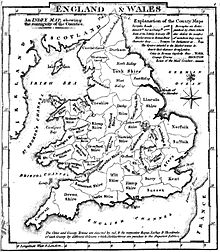

Structure of local governments[edit]

The beginnings of the English local government system date back to the Middle Ages when a peace judge represented the king in each county. England remained an example of a country whose territorial administration relied solely on local government bodies until the end of the 19th century. They had broad powers and evolved towards decentralization. In the 19th century, local government reforms were carried out.[g][14] The first stage, initiated between 1832 and 1835, concerned cities. Democratic elections were introduced for city councils and executive bodies of mayors and aldermen. County government was also reformed.

In 1871, a separate ministry was introduced to standardize and control the activities of local government – the Local Government Board. In 1888, administration passed into the hands of county councils operating in 52 newly established administrative counties (the second stage of reform). In 1894, counties were divided into urban and rural districts.[h][14] District councils were established, and in larger parishes, parish councils were formed, creating a two-tier (counties, districts)[i][14] and three-tier administrative division (counties, districts, and parishes).[j][14] Temporarily, a five-tier model of local government took shape there, consisting of:

- Counties,

- municipalities,

- districts,

- social welfare unions,

- parishes.

London had a separate local government organization. Executive power was exercised by the London County Council, which was supported by district councils. Councillors met in plenary sessions and in individual committees. They also employed professional officials who acted as executors of the councils' orders. In addition to the comprehensive and integrated local government administration, non-integrated administration began to develop. To streamline, standardize, and control local government, the Local Government Board was established.

Division of powers of local government structures[edit]

The essence of the administrative division in the UK was the division of competencies, which rested with individual local government units. The respective councils had responsibility for:

- County councils: education, maintenance of public roads, social care, fire protection, police, and libraries. The council was led by a chairman.

- District councils: construction, local taxes, cemetery maintenance, and waste disposal. The council was chaired by a chairman, and in borough-type districts, by a mayor.

- Parish councils: maintenance of allotment gardens and urban greenery. The council was led by a chairman. In parishes where there was no council, the decision-making body was the parish trustee, chaired by the chairman of the parish meeting, a councilor from the district council.[45]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The beginnings of the Irish Parliament date back to the late 15th century. It could only convene with the king's consent. The legislative system was subordinated to the English one. In 1536, the parliament recognized King Henry VIII Tudor as the head of the Irish Church (in 1541, he became the King of Ireland, as did his successors). At the same time, a viceroy of Ireland was appointed. Until the end of the 18th century, the Irish Parliament was represented solely by Anglicans. It consisted of the House of Commons, which had 300 members, and the House of Lords, which was composed of several dozen peers (their number underwent continuous changes – they constituted about 50% of the members of the House) and Anglican bishops, forming the second elite group of the higher authority. The term of office in parliament was not specified. Its members took an oath in which they officially condemned and questioned the dogma of transubstantiation. The electoral system in Ireland was based on rotten boroughs. On 2 July 1800, the English Parliament passed the Act of Union, confirmed by the Irish Parliament on August 1. The Union came into effect on 1 January 1801. The Irish agreed to a political union on the condition of equal rights for Catholics and Protestants. However, the promises were not kept, due to the resistance of King George III and English parliamentarians. Under this agreement, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was established. Wales and Scotland were simultaneously included in the United Kingdom (since 1707). The Irish were allocated 132 seats in the British Parliament, with 100 seats in the House of Commons and 32 seats in the House of Lords. At the same time, the Churches were merged: the Irish with the Anglican Church.

- ^ The statute prevented the creation of the so-called "professional politician" class. It also broke with the privilege that guaranteed participation in elections to the House of Commons by virtue of land ownership. However, it maintained a high property censorship.

- ^ The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 abolished the previous Test Act of 1673, which limited the rights of Catholics. From then on, Catholics acquired full civil and public rights, including the right to hold office and sit in Parliament. The act applied to both British and Irish Catholics. This act was prompted by the threat of a mass Irish uprising, following the notable electoral success of D. O'Connell, who as a Catholic could not sit in Parliament (Johnson (2002, p. 280)).

- ^ Chartism helped improve the living conditions of the working classes (Trevelyan (1963, p. 763)).

- ^ From the merger of the Independent Labour Party, the Fabian Society and the Democratic Federation, the Labour Party was formed (1900).

- ^ They were the first life lords in British history (Majkowska (2008, p. 64)).

- ^ In the UK, there is no self-government, but local government.

- ^ Until the 19th century, counties were divided into parishes.

- ^ Not all districts were divided into parishes.

- ^ In addition to parishes, there were so-called boroughs, smaller towns created on the basis of royal charters in the county. This division functioned until 1972. The current one is in effect under The Local Government Act, which came into force in 1974.

References[edit]

- ^ Staroń, M. "Historia Irlandii" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2010-03-11. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ a b Ogrodowczyk, P. "Znaczenie konstytucji w państwie demokratycznym" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2010-05-05. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ a b c d Ogrodowczyk, P.; Ostrowski, J. (2016-03-17). "Analiza porównawcza modeli rządów". Komentarze Polityczne (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ a b c Nawrot, A., ed. (2007). Encyklopedia Historia (in Polish). Kraków. p. 354. ISBN 978-83-7327-782-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Podstawy prawne". umwd.dolnyslask.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ a b Bazylow (1986, p. 192)

- ^ Trevelyan (1963, pp. 753–755)

- ^ Trevelyan (1963, p. 760); Żywczyński (1997, p. 291); Bazylow (1986, p. 192)

- ^ Zins (2001, p. 282)

- ^ a b "Pozycja władz lokalnych w regulacjach prawnych i podział terytorialny ze względu na ilość szczebli władzy lokalnej" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ a b Żywczyński (1997, p. 294)

- ^ Trevelyan (1963, pp. 756–757)

- ^ Johnson (2002, p. 308)

- ^ a b c d e "Administracja lokalna w Anglii" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2012-12-09. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ Majkowska (2008, p. 70)

- ^ Johnson (2002, p. 312)

- ^ Majkowska (2008, p. 54)

- ^ a b c d e f Zins (2001, p. 281)

- ^ Żywczyński (1997, p. 291)

- ^ a b Majkowska (2008, p. 55)

- ^ "Akt emancypacji katolików". portalwiedzy.onet.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2010-01-23. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ Majkowska (2008, p. 59)

- ^ Zins (2001, p. 298)

- ^ Żywczyński (1997, pp. 287–289); Bazylow (1986, pp. 201–202)

- ^ Pajewski (1998, p. 123)

- ^ Majkowska (2008, p. 64)

- ^ Pilkington, Colin (1999). The Politics today companion to the British Constitution. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7190-5302-3.

- ^ Trevelyan (1963, p. 762)

- ^ Bazylow (1986, pp. 197–198)

- ^ Pajewski (1998, p. 124)

- ^ Collins, R. "History of the Labour Party". Archived from the original on 2010-05-06. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ Majkowska (2008, pp. 70–71)

- ^ a b c d e Kania, P. "Monarchie konstytucyjne schyłku XVIII w. – próba porównania" (in Polish). Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ Minałto, M. "Ustawa o prawach w Anglii". www.gazeta.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Johnson (2002, p. 270)

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Historia – Reformy i modernizacje ustroju w Wlk. Brytanii w XIX I XX w." historia.wiedza.diaboli.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ a b c d Majkowska (2008, p. 128)

- ^ Johnson (2002, p. 259)

- ^ Majkowska (2008, pp. 60–61)

- ^ "History of the Parliamentary Archives. Surviving the 1834 fire". UK Parliament Website. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "Big Ben i brytyjski parlament". www.emito.net (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Majkowska (2008, p. 66)

- ^ Majkowska (2008, p. 131)

- ^ a b "Royal Courts Of Justice visitors guide". Her Majesty’s Courts Service. Archived from the original on 2010-07-24. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- ^ Lasocka, D. "Samorządy w Unii Europejskiej" (PDF) (in Polish). p. 44. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bazylow, Ludwik (1986). Historia Powszechna 1789-1918 (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. ISBN 83-05-11231-4. OCLC 835900285.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Johnson, Paul (2002). Historia Anglików (in Polish). Translated by Mikos, Jarosław. Gdańsk: Marabut. ISBN 83-916703-2-5. OCLC 749258064.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Pajewski, J. (1998). Historia Powszechna 1871-1918 (in Polish). Vol. 6. Warsaw. ISBN 83-01-03881-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Trevelyan, G. M. (1963). Historia Anglii (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zins, Henryk (2001). Historia Anglii (in Polish). Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. ISBN 83-04-04589-3. OCLC 68633568.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Żywczyński, Mieczysław (1997). Historia Powszechna 1789-1870 (in Polish). Vol. 5. Warsaw: Wydaw. Naukowe PWN. ISBN 83-01-11992-6. OCLC 749422493.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Majkowska, Olga (2008). Pozycja parlamentu brytyjskiego w świetle działania systemu dwupartyjnego (PDF) (in Polish). Katowice. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links[edit]

- Bloy, Marjie. "Victorian Legislation: a Timeline". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- Mazur, S. "Administracja publiczna w wybranych państwach Europy Zachodniej" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- "Privy Council Office". privy-council.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2006-12-06. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- "The Supreme Court". supremecourt.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- "UK Parliament Website". parliament.uk. Retrieved 2010-05-08.