Ennigaldi-Nanna: Difference between revisions

Eticketgirl (talk | contribs) Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

overhaul using more (recent) sources |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Babylonian princess}} |

|||

{{Infobox |

{{Infobox monarch |

||

| name = Bel-Shalti-Nanna |

|||

| name = Ennigaldi |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| title = Princess of [[Neo-Babylonian Empire|Babylon]] |

|||

| birth_date = 6th century BCE |

|||

| image = |

|||

| caption = [[Nabonidus]], father of Ennigaldi-Nanna |

|||

| caption = |

|||

| office = [[Princess]] of Babylonia |

|||

| |

| succession = [[High priestess]] of [[Ur]] |

||

| reign = 547 BC – ? |

|||

| father = [[Nabonidus]] |

|||

| predecessor = Daughter of [[Nebuchadnezzar I]]<br/><small>(12th century BC)</small> |

|||

| relatives = [[Belshazzar]] |

|||

| dynasty = [[Chaldean dynasty]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| mother = [[Nitocris of Babylon|Nitocris]] (?) |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Bel-Shalti-Nanna''', later known as '''Ennigaldi-Nanna''' ([[Babylonian cuneiform]]: [[File:Ennigaldi-Nanna_in_Akkadian.png|120x120px]]<!--an image file is used here since there currently is no unicode encoding or font supporting Neo-Babylonian signs--> ''En-nígaldi-Nanna''),<ref>[http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/ribo/babylon7/Q005431/sources Schaudig, AOAT 256 2.7; i 25], [[ORACC]]</ref> and commonly called just '''Ennigaldi''',<ref name="Leon">{{cite book |last=León |first=Vicki |url=https://archive.org/details/uppitywomenofanc00leon/page/36 |title=Uppity Women of Ancient Times |date=1995 |publisher=[[Conari Press]] |isbn=1-57324-010-9 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/uppitywomenofanc00leon/page/36 36–37]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Moniz |first=Melissa |date=2021 |title=Source of Nostalgia and Archival Recreation: The South African Hellenic Archive |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/00043389.2021.1983244 |journal=De Arte |volume=56 |issue=1 |pages=85 |doi=10.1080/00043389.2021.1983244 |issn=0004-3389}}</ref> was a princess of the [[Neo-Babylonian Empire]] and high priestess (''entu'') of [[Ur]]. As the first ''entu'' in six centuries, serving as the "human wife" of the moon-god [[Sin (mythology)|Sin]], Ennigaldi held large religious and political power. She is most famous today for founding [[Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum|a museum]] in Ur {{Circa}} 530 BC. Ennigaldi's museum showcased cataloged and labelled artifacts from the preceding 1,500 years of Mesopotamian history and is often considered to have been the first museum in world history.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=Cohen |first=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Cw02EAAAQBAJ |title=Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past |date=2022 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-9821-9580-9 |pages=487 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":3">{{Cite book |last=Grande |first=Lance |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZZYtDwAAQBAJ |title=Curators: Behind the Scenes of Natural History Museums |date=2017 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-19275-8 |pages=x |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite book |last=Walhimer |first=Mark |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NO_5CQAAQBAJ |title=Museums 101 |date=2015 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-4422-3019-4 |pages=6 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":5">{{Cite book |last=Quinn |first=Therese |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OwbZDwAAQBAJ |title=About Museums, Culture, and Justice to Explore in Your Classroom |date=2020 |publisher=Teachers College Press |isbn=978-0-8077-6343-8 |pages=11–12 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== Family == |

|||

'''Bel-Shalti-Nanna''' or '''Bel-Shalti-Nannar''', named also '''Ennigaldi-Nanna''' ([[Babylonian cuneiform]]: [[File:Ennigaldi-Nanna in Akkadian.png|120x120px]]<!--an image file is used here since there currently is no unicode encoding or font supporting Neo-Babylonian signs--> ''En-nígaldi-Nanna''),<ref>[http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/ribo/babylon7/Q005431/sources Schaudig, AOAT 256 2.7; i 25], [[ORACC]]</ref> was a [[Babylonia]]n princess who [[Floruit|flourished]] around 554 BCE. She was the daughter of [[Nabonidus]] (Nabu-na'id), the last [[Neo-Babylonian]] king and ruler of the city of [[Ur]] (modern Tell el-Muqayyar, Iraq),<ref name=anzovin>{{cite book |last=Anzovin |first=Steven |last2=Kane |first2=Joseph Nathan |last3=Podell |first3=Janet |title=Famous First Facts |url=https://archive.org/details/famousfirstfacts00anzo/page/69 |year=1997 |publisher=[[H. W. Wilson Company|H. W. Wilson]] |isbn=0-8242-0958-3 |page=[https://archive.org/details/famousfirstfacts00anzo/page/69 69] |quote=The first museum known to historians was that of Ennigaldi-Nanna, the daughter of Nabu-na'id (Nabonidus), the last king to Babylonia }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Casey |first=Wilson |title=Firsts: Origins of Everyday Things That Changed the World |publisher=[[Penguin Books]] |year=2009 |isbn=1-59257-924-8}}</ref><ref name=Leon>{{cite book |last=León |first=Vicki |title=Uppity Women of Ancient Times |url=https://archive.org/details/uppitywomenofanc00leon/page/36 |publisher=[[Conari Press]] |date=1995 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/uppitywomenofanc00leon/page/36 36–37] |isbn=1-57324-010-9 }}</ref><ref name=Britannica>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Bel-Shalti-Nanna |encyclopedia=[[The New Encyclopædia Britannica]] |volume=2 |year=1997 |page=[https://archive.org/details/newencyclopaedia03ency/page/481 481] |isbn=0-85229-633-9 }}</ref> and sister of [[Belshazzar]].<ref name="BudgeBudge2005">{{cite book|author1=E. a. Budge Budge|author2=Sir Ernest a. Wallis Budge|title=The Book of the Cave of Treasures|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GKCgR1kdBnIC&pg=PA278|accessdate=18 October 2012|date=30 November 2005|publisher=Cosimo, Inc.|isbn=978-1-59605-335-9|page=278}}</ref> She served as an ''entum'' – [[high priestess]] – in [[Ur]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Woolley |first=Leonard |author-link=Leonard Woolley |title=Ur, la ciudad de los caldeos |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xkJkCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT134 |publisher=[[Fondo de Cultura Económica]] |date=November 4, 2014 |page=134 |isbn=9786071624376}}</ref> She was called the "priestess of [[Sin (mythology)|Sin]]" (the god of the moon).<ref name="Babylonian Historical Texts Relating to the Capture and Downfall of Babylon">{{cite book|title=Babylonian Historical Texts Relating to the Capture and Downfall of Babylon|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vc4OAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA56|accessdate=18 October 2012|publisher=Taylor & Francis|page=56 }}</ref> |

|||

Ennigaldi was the daughter of [[Nabonidus]], who ruled as [[king of Babylon]] from 556 to 539 BC.<ref name="Leon" /> She had at least three siblings: the brother [[Belshazzar]] and the sisters Ina-Esagila-risat and Akkabuʾunma.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Weiershäuser |first1=Frauke |url=https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/73674/1/RINBE2_OAPDF.pdf |title=The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon |last2=Novotny |first2=Jamie |publisher=Eisenbrauns |year=2020 |isbn=978-1646021079 |pages=4}}</ref> Nabonidus was genealogically unconnected to previous Babylonian kings but he might have been married to a daughter of the previous ruler [[Nebuchadnezzar II]] (605–562 BC), which would make Ennigaldi and her siblings into Nebuchadnezzar's grandchildren.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wiseman |first=Donald J. |title=The Cambridge Ancient History: III Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2003 |isbn=0-521-22717-8 |editor-last=Boardman |editor-first=John |edition=2nd |location= |page=244 |pages= |chapter=Babylonia 605–539 B.C. |author-link=Donald Wiseman |editor-last2=Edwards |editor-first2=I. E. S. |editor-last3=Hammond |editor-first3=N. G. L. |editor-last4=Sollberger |editor-first4=E. |editor-last5=Walker |editor-first5=C. B. F. |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OGBGauNBK8kC&q=Neriglissar |orig-year=1991}}</ref> The name of their mother is unknown but she may have been the figure remembered in later tradition under the name [[Nitocris of Babylon|Nitocris]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Shea |first=William H. |date=1982 |title=Nabonidus, Belshazzar, and the Book of Daniel: an Update |url=https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1547&context=auss |journal=Andrews University Seminary Studies |volume=20 |issue=2 |pages=137–138}}</ref> |

|||

Nabonidus had great interest in [[archaeology]]. He conducted extensive excavations, included more allusions to past rulers in his writings than most other kings and is the earliest known person in history to attempt to chronologically date archaeological artifacts.<ref name=":6">{{Cite book |last=Beaulieu |first=Paul-Alain |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2250wnt |title=Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon (556-539 BC) |publisher=Yale University Press |year=1989 |isbn=9780300043143 |pages=138–140, 230, 249 |jstor=j.ctt2250wnt |oclc=20391775 |author-link=Paul-Alain Beaulieu}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Silverberg |first=Robert |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ic2za8bZeYAC&pg=PR8 |title=Great Adventures in Archaeology |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |year=1997 |isbn=978-0803292475 |pages=viii}}</ref> Ennigaldi's interest in archaeology and history probably stemmed from her father.<ref name="Leon" /> |

|||

==Life== |

|||

Ennigaldi lived in the 6th century BCE. She had 3 [[career]]s. One was as a school administrator, running a school for [[priest]]esses that was already over eight centuries old when she took over. Another was as a museum curator. And still another was as a high priestess (the ''en''-priestess).<ref name=Leon/><ref name=Britannica/> Archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley notes in his work that her father king Nabonidus called her Belshalti-Nannar when she became the High Priestess of Nannar at Ur.<ref>Woolley, ''Excavations at Ur...'', p. 235</ref> Ennigaldi became high priestess in 547 BCE. Her grandmother ([[Addagoppe of Harran]]) was also a high priestess, but was at this time already deceased.<ref name=Leon/> |

|||

== Career == |

|||

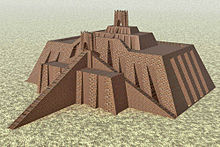

Ennigaldi received her additional name of Nanna because she was a high priestess of the male god [[Sin (mythology)|Nanna]] (equivalent to the Old Babylonian moon deity Sin).<ref name=Leon/> She devoted much of her religious time in the evenings to Nanna in a small blue room on top of the [[Great Ziggurat of Ur]].<ref name=Leon/> This worship temple at Ur for Ennigaldi, the high priestess, was called Nanna-Suen and was rebuilt by her father (it was originally rebuilt by Enanedu in the reign of her brother [[Rim-Sin I]]).<ref>George, p. 92</ref> This temple is also referred to as the "giparu" for the ''entu''-priestess (high priestess) and was considered a sacred place for "private cultic use."<ref Name="Enheduanna64">Enheduanna, p. 64</ref> |

|||

=== High priestess === |

|||

The "giparu" was for the high priestess only (moon goddess) and men were strictly forbidden to enter it. The "giparu" was built and rebuilt several times following [[History of Sumer#Early Dynastic period|Early Dynastic]] times. Ennigaldi's father, King Nabonidus, rebuilt the "giparu" for Ennigaldi around 590 BCE, not knowing at the time that this would be the last time it was rebuilt.<ref Name="Enheduanna64"/><ref>Weadock, pp. 101-128</ref> He recorded on brick tablets {{cquote| ''...along the side of Egipar the house of Ennigaldi-Nanna, my daughter, entu-priestess of Sin, I built new.''<ref>Weadock, pp. 113</ref>}} |

|||

[[File:Ziggurat of ur.jpg|left|thumb|Reconstruction of the [[Ziggurat of Ur]]]] |

|||

In 547 BC,<ref name="Leon" /> Nabonidus revived the office of ''entu'' ("high priestess") of Ur, which had been vacant since the time of [[Nebuchadnezzar I]] in the 12th century BC, and named Ennigaldi to this office.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Cousin |first=Laura |date=2020 |title=Sweet Girls and Strong Men: Onomastics and Personality Traits in First-Millennium Sources |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26977772 |journal=Die Welt des Orients |volume=50 |issue=2 |pages=342 |doi=10.2307/26977772 |issn=0043-2547}}</ref> The ''entu'' was devoted to the moon-god [[Sin (mythology)|Sin]] (known as Nanna in [[Sumer|Sumerian]] times) and was the highest-ranking priestess in the country, supposedly divinely elected by the god himself and revealed through omens. All known ''entu'' were of royal blood, having been sisters or daughters of kings.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Weadock |first=Penelope N. |date=1975 |title=The Giparu at Ur |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/4200011 |journal=Iraq |volume=37 |issue=2 |pages=101–128 |doi=10.2307/4200011 |issn=0021-0889}}</ref> Nabonidus was supposedly inspired to restore the office after a partial [[lunar eclipse]] in 554 BC, which he interpreted as an omen, and the find of a [[stele]] created by Nebuchadnezzar I showing the investment of that king's daughter as ''entu''.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Nielsen |first=John P. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lx9WDwAAQBAJ |title=The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in History and Historical Memory |date=2018 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-30048-9 |language=en |chapter=3.3. Conclusions" and "6.2. Nebuchadnezzar I in the Neo-Babylonian Empire}}</ref> According to Nabonidus, he selected Ennigaldi as ''entu'' only after having learnt through lengthy [[divination]] that she was the choice of Sin.<ref name=":1" /> The name Ennigaldi-Nanna was in all likelihood assumed at this time as her priestess name, since it means "Nanna requests an ''entu''".<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

As ''entu'', Ennigaldi would have devoted much of her religious time in the evenings to Nanna in a small blue room on top of the [[Ziggurat of Ur]].<ref name="Leon" /> Her official dwelling was a building called the ''giparu'', located adjacent to the ziggurat. The ''giparu'' had been in ruins for centuries but was rebuilt for Ennigaldi on the orders of Nabonidus.<ref name=":1" /> The most important part of the religious role of the ''entu'' was to serve as the human wife of the god Sin and to perform rites relating to this sacred marriage. What these rites entailed is poorly known. The ''entu'' also had to pray for the life of the king, who served as the living embodiment of Babylonia's prosperity, and had to provide conformt and adornment for the goddess [[Ningal]], Sin's divine consort. The ''entu'' also served as the manager of the considerable estates and wealth belonging to the temple complex of Ur.<ref name=":1" /> In addition to these duties, Ennigaldi also ran, and possibly taught in, a school for aspiring priestesses from upper-class Babylonian families. By the time Ennigaldi became ''entu'', this school had been in continuous operation for more than eight hundred years. The school taught a special women's scribal dialect called ''[[Emesal]]''.<ref name="Leon" /> |

|||

==The Palace of the High Priestess Bel-Shalti-Nannar== |

|||

While excavating in [[Ur]], [[Sir Leonard Woolley]] discovered a room built for Bel-Shalti-Nannar around 550 B.C.E. The room is known as the Palace of the High Priestess Bel-Shalti-Nannar.<ref>Berrett, LaMar C. 1973. Discovering the world of the Bible. Provo, Utah: Young House. 217.</ref> The palace shares some design features with the South palace at Babylon, but on smaller scale. It is located on a trapezoidal plot by North Harbor of [[Ur]].<ref>Potts, Daniel T. 2012. A companion to the archaeology of the ancient Near East. Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell. 924.</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

It contained objects dating back to 1400 B.C.E., 1700 B.C.E., and 2050 B.C.E. A clay tablet bore copies of very ancient inscriptions together with another inscription explaining that the earliest ones had been found and copied out “for the marvel of the beholders.” These clay tablets are considered the oldest museum catalogue.<ref>Keller, Werner, and Joachim Rehork. 1981. The Bible as history. New York: Morrow. 295-6.</ref> The room was a museum, and Bel-Shalti-Nannar was a collector of antiquities.<ref>Buried History: A Quarterly Journal of Biblical Archaeology. Vol 5, No 1, March, 1969. page 13.</ref> Statue fragments from a diorite statue dedicated by Sulgi to the goddess Ninsuna of Ur were also found, as well as clay dog figurines.<ref>Frayne, Douglas. 1997. Ur III period, 2112-2004 BC. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 159.</ref> |

|||

Her name, and the dedication of the palace, is mentioned by [[Nabonidus]] in several inscriptions on clay cylinders: “I built anew the house of Bel-shalti-Nannar, my daughter, the priestess of Sin. I purified my daughter and offered her to Sin..." and "May Bêl-shalti-Nannar the daughter, the beloved of my heart, be strong before them; and may her word prevail.”<ref>Smith, Sidney. 1924. Babylonian historical texts relating to the capture and downfall of Babylon. London: Methuen & Co., ltd. Page 56.</ref> |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

Along with her father, [[Nabonidus]], Bel-Shalti-Nannar is known for being responsible for first controlled excavation and museum display. It is believed she helped to found a series of museums related to the discoveries made by Nabonidus.<ref>{{cite thesis |last=Ouzman |first=Sven |year=2008 |title=Imprints: an archaeology of identity in post-apartheid southern Africa |type=Ph.D. in anthropology |publisher=University of California, Berkeley |page=36 |id={{ProQuest|304695098}} }}</ref> She is memorialized in ''[[The Dinner Party]]'' by [[Judy Chicago]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Main|Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum}} |

{{Main|Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum}} |

||

[[File:Ur-Nassiriyah.jpg|thumb| |

[[File:Ur-Nassiriyah.jpg|thumb|Ruins of [[Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum]]]] |

||

The reign of Ennigaldi's father came to an end when the [[Neo-Babylonian Empire]] was conquered by [[Cyrus the Great]] of the [[Achaemenid Empire]] in 539 BC. Nabonidus appears to have been allowed to live and retire in peace.<ref name=":6" /> The change in government does not appear to have impacted Ennigaldi's position since she {{Circa}} 530 BC<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Wherry |first=Frederick F. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kRwzCwAAQBAJ |title=The SAGE Encyclopedia of Economics and Society |last2=Schor |first2=Juliet B. |date=2015 |publisher=SAGE Publications |isbn=978-1-4522-1797-0 |pages=1135 |language=en}}</ref> founded a museum containing artifacts from past Mesopotamian civilizations, located about five hundred feet southeast of the ziggurat.<ref name=":2" /> Ennigaldi's museum is often considered the first museum in world history.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> Some of the objects on display may have been personally excavated by Ennigaldi and her father.<ref name="Leon" /><ref name=":5" /> Most of the artifacts dated to the 20th century BC,<ref name=":7">{{Cite book |last=Nepo |first=Mark |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QNecDwAAQBAJ |title=More Together Than Alone: Discovering the Power and Spirit of Community in Our Lives and in the World |date=2019 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-5011-6784-3 |pages=113 |language=en}}</ref> though the collection covered a timespan of about 1,500 years<ref name=":8">{{Cite book |last=Hopkins |first=Owen |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hodIEAAAQBAJ |title=The Museum: From its Origins to the 21st Century |date=2021 |publisher=Frances Lincoln |isbn=978-0-7112-5457-2 |pages=43 |language=en}}</ref> (c. 2100–600 BC).<ref name=":3" /> Some of the artifacts on display had once belonged to Nebuchadnezzar II.<ref name=":7" /> Ennigaldi developed a research program around the museum's collection of artifacts<ref name=":3" /> and she was presumably personally responsible for cataloging and labelling the collections.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Gartner |first=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2Z_VDAAAQBAJ |title=Metadata: Shaping Knowledge from Antiquity to the Semantic Web |date=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-319-40893-4 |pages=15 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

Ennigaldi is noted by historians as being the creator of the world's first museum,<ref name=anzovin/><ref Name="Harvey">Harvey, p. 20 ''Princess Ennigaldi-Nanna collected antiques from the southern regions of Mesopotamia, which she stored in a temple at Ur - the first known museum in the world. ''</ref> a museum of antiquities.<ref>Gathercole, p. 12</ref> |

|||

The priestess school Ennigaldi operated around 530 BCE was for upper-class young women. Ennigaldi spent much less time on corporal punishment because she had a devoted captive audience, even though otherwise her school resembled the other [[Sumer|Sumerian scribal schools]] in its teaching techniques, [[curriculum]], and student equipment. Literate women at her school were taught a special dialect called [[Emesal]].<ref name=Leon/> |

|||

The subsequent fate of Ennigaldi is unknown.<ref name=":3" /> Her museum ceased operations at the latest around 500 BC;<ref name=":3" /> changing climate conditions (including a change in the course of the [[Euphrates]] river, a drought, and the recession of the [[Persian Gulf]]) caused Ur to rapidly decline under Achaemenid rule and rendered the city uninhabited by that time.<ref name=":3" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Romain |first=William F. |date=2019 |title=Lunar alignments at Ur: Entanglements with the Moon God Nanna |url=https://journal.equinoxpub.com/JSA/article/view/17542 |journal=Journal of Skyscape Archaeology |language=en |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=154 |doi=10.1558/jsa.39074 |issn=2055-3498}}</ref> The ruins of the museum were discovered by the British archaeologist [[Leonard Woolley]] during excavations of the Ur temple complex in 1925. <ref name=":8" /> Woolley discovered objects whose ages varied by centuries, neatly arranged side-by-side. Soon thereafter, clay tablets and cones containing descriptions of the objects and written in three different languages were also uncovered.<ref name="Leon" /> Also discovered in the ruins were tablets containing lists of ojects, the earliest known museum catalogs.<ref name=":5" /> |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== |

== References == |

||

<references /> |

|||

*Casey, Wilson, ''Firsts: Origins of Everyday Things That Changed the World'', Penguin, 2009, {{ISBN|1-59257-924-8}} |

|||

*Enheduanna, ''Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna'', University of Texas Press, 2000, {{ISBN|0-292-75242-3}} |

|||

*George, A. R., ''House Most High: the Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia'', Eisenbrauns, 1993, {{ISBN|0-931464-80-3}} |

|||

*Gathercole, P.W., ''The Politics of the Past'', Psychology Press, 1994, {{ISBN|0-415-09554-9}} |

|||

*Harvey, Edmund H., ''Reader's Digest Book of Facts'', Reader's Digest Association, 1987, {{ISBN|0-89577-256-6}} |

|||

*Weadock, Penelope N., ''The Giparu at Ur'', Iraq - Vol. 37, No. 2 (Autumn, 1975) JSTOR |

|||

*Woolley, Leonard, ''Excavations at Ur - A Record of Twelve Years' Work'' London, |

|||

[[Category:6th-century BC clergy]] |

[[Category:6th-century BC clergy]] |

||

Revision as of 20:30, 4 August 2022

| Ennigaldi | |

|---|---|

| Princess of Babylon | |

| High priestess of Ur | |

| Reign | 547 BC – ? |

| Predecessor | Daughter of Nebuchadnezzar I (12th century BC) |

| Dynasty | Chaldean dynasty |

| Father | Nabonidus |

| Mother | Nitocris (?) |

Bel-Shalti-Nanna, later known as Ennigaldi-Nanna (Babylonian cuneiform: ![]() En-nígaldi-Nanna),[1] and commonly called just Ennigaldi,[2][3] was a princess of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and high priestess (entu) of Ur. As the first entu in six centuries, serving as the "human wife" of the moon-god Sin, Ennigaldi held large religious and political power. She is most famous today for founding a museum in Ur c. 530 BC. Ennigaldi's museum showcased cataloged and labelled artifacts from the preceding 1,500 years of Mesopotamian history and is often considered to have been the first museum in world history.[4][5][6][7]

En-nígaldi-Nanna),[1] and commonly called just Ennigaldi,[2][3] was a princess of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and high priestess (entu) of Ur. As the first entu in six centuries, serving as the "human wife" of the moon-god Sin, Ennigaldi held large religious and political power. She is most famous today for founding a museum in Ur c. 530 BC. Ennigaldi's museum showcased cataloged and labelled artifacts from the preceding 1,500 years of Mesopotamian history and is often considered to have been the first museum in world history.[4][5][6][7]

Family

Ennigaldi was the daughter of Nabonidus, who ruled as king of Babylon from 556 to 539 BC.[2] She had at least three siblings: the brother Belshazzar and the sisters Ina-Esagila-risat and Akkabuʾunma.[8] Nabonidus was genealogically unconnected to previous Babylonian kings but he might have been married to a daughter of the previous ruler Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC), which would make Ennigaldi and her siblings into Nebuchadnezzar's grandchildren.[9] The name of their mother is unknown but she may have been the figure remembered in later tradition under the name Nitocris.[10]

Nabonidus had great interest in archaeology. He conducted extensive excavations, included more allusions to past rulers in his writings than most other kings and is the earliest known person in history to attempt to chronologically date archaeological artifacts.[11][12] Ennigaldi's interest in archaeology and history probably stemmed from her father.[2]

Career

High priestess

In 547 BC,[2] Nabonidus revived the office of entu ("high priestess") of Ur, which had been vacant since the time of Nebuchadnezzar I in the 12th century BC, and named Ennigaldi to this office.[13] The entu was devoted to the moon-god Sin (known as Nanna in Sumerian times) and was the highest-ranking priestess in the country, supposedly divinely elected by the god himself and revealed through omens. All known entu were of royal blood, having been sisters or daughters of kings.[14] Nabonidus was supposedly inspired to restore the office after a partial lunar eclipse in 554 BC, which he interpreted as an omen, and the find of a stele created by Nebuchadnezzar I showing the investment of that king's daughter as entu.[15] According to Nabonidus, he selected Ennigaldi as entu only after having learnt through lengthy divination that she was the choice of Sin.[14] The name Ennigaldi-Nanna was in all likelihood assumed at this time as her priestess name, since it means "Nanna requests an entu".[13]

As entu, Ennigaldi would have devoted much of her religious time in the evenings to Nanna in a small blue room on top of the Ziggurat of Ur.[2] Her official dwelling was a building called the giparu, located adjacent to the ziggurat. The giparu had been in ruins for centuries but was rebuilt for Ennigaldi on the orders of Nabonidus.[14] The most important part of the religious role of the entu was to serve as the human wife of the god Sin and to perform rites relating to this sacred marriage. What these rites entailed is poorly known. The entu also had to pray for the life of the king, who served as the living embodiment of Babylonia's prosperity, and had to provide conformt and adornment for the goddess Ningal, Sin's divine consort. The entu also served as the manager of the considerable estates and wealth belonging to the temple complex of Ur.[14] In addition to these duties, Ennigaldi also ran, and possibly taught in, a school for aspiring priestesses from upper-class Babylonian families. By the time Ennigaldi became entu, this school had been in continuous operation for more than eight hundred years. The school taught a special women's scribal dialect called Emesal.[2]

Museum curator

The reign of Ennigaldi's father came to an end when the Neo-Babylonian Empire was conquered by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire in 539 BC. Nabonidus appears to have been allowed to live and retire in peace.[11] The change in government does not appear to have impacted Ennigaldi's position since she c. 530 BC[4][5][6][16] founded a museum containing artifacts from past Mesopotamian civilizations, located about five hundred feet southeast of the ziggurat.[4] Ennigaldi's museum is often considered the first museum in world history.[4][5][6][7] Some of the objects on display may have been personally excavated by Ennigaldi and her father.[2][7] Most of the artifacts dated to the 20th century BC,[17] though the collection covered a timespan of about 1,500 years[18] (c. 2100–600 BC).[5] Some of the artifacts on display had once belonged to Nebuchadnezzar II.[17] Ennigaldi developed a research program around the museum's collection of artifacts[5] and she was presumably personally responsible for cataloging and labelling the collections.[19]

The subsequent fate of Ennigaldi is unknown.[5] Her museum ceased operations at the latest around 500 BC;[5] changing climate conditions (including a change in the course of the Euphrates river, a drought, and the recession of the Persian Gulf) caused Ur to rapidly decline under Achaemenid rule and rendered the city uninhabited by that time.[5][20] The ruins of the museum were discovered by the British archaeologist Leonard Woolley during excavations of the Ur temple complex in 1925. [18] Woolley discovered objects whose ages varied by centuries, neatly arranged side-by-side. Soon thereafter, clay tablets and cones containing descriptions of the objects and written in three different languages were also uncovered.[2] Also discovered in the ruins were tablets containing lists of ojects, the earliest known museum catalogs.[7]

References

- ^ Schaudig, AOAT 256 2.7; i 25, ORACC

- ^ a b c d e f g h León, Vicki (1995). Uppity Women of Ancient Times. Conari Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 1-57324-010-9.

- ^ Moniz, Melissa (2021). "Source of Nostalgia and Archival Recreation: The South African Hellenic Archive". De Arte. 56 (1): 85. doi:10.1080/00043389.2021.1983244. ISSN 0004-3389.

- ^ a b c d Cohen, Richard (2022). Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past. Simon and Schuster. p. 487. ISBN 978-1-9821-9580-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grande, Lance (2017). Curators: Behind the Scenes of Natural History Museums. University of Chicago Press. pp. x. ISBN 978-0-226-19275-8.

- ^ a b c Walhimer, Mark (2015). Museums 101. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4422-3019-4.

- ^ a b c d Quinn, Therese (2020). About Museums, Culture, and Justice to Explore in Your Classroom. Teachers College Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-8077-6343-8.

- ^ Weiershäuser, Frauke; Novotny, Jamie (2020). The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon (PDF). Eisenbrauns. p. 4. ISBN 978-1646021079.

- ^ Wiseman, Donald J. (2003) [1991]. "Babylonia 605–539 B.C.". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: III Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.

- ^ Shea, William H. (1982). "Nabonidus, Belshazzar, and the Book of Daniel: an Update". Andrews University Seminary Studies. 20 (2): 137–138.

- ^ a b Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1989). Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon (556-539 BC). Yale University Press. pp. 138–140, 230, 249. ISBN 9780300043143. JSTOR j.ctt2250wnt. OCLC 20391775.

- ^ Silverberg, Robert (1997). Great Adventures in Archaeology. University of Nebraska Press. pp. viii. ISBN 978-0803292475.

- ^ a b Cousin, Laura (2020). "Sweet Girls and Strong Men: Onomastics and Personality Traits in First-Millennium Sources". Die Welt des Orients. 50 (2): 342. doi:10.2307/26977772. ISSN 0043-2547.

- ^ a b c d Weadock, Penelope N. (1975). "The Giparu at Ur". Iraq. 37 (2): 101–128. doi:10.2307/4200011. ISSN 0021-0889.

- ^ Nielsen, John P. (2018). "3.3. Conclusions" and "6.2. Nebuchadnezzar I in the Neo-Babylonian Empire". The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in History and Historical Memory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-30048-9.

- ^ Wherry, Frederick F.; Schor, Juliet B. (2015). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Economics and Society. SAGE Publications. p. 1135. ISBN 978-1-4522-1797-0.

- ^ a b Nepo, Mark (2019). More Together Than Alone: Discovering the Power and Spirit of Community in Our Lives and in the World. Simon and Schuster. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-5011-6784-3.

- ^ a b Hopkins, Owen (2021). The Museum: From its Origins to the 21st Century. Frances Lincoln. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7112-5457-2.

- ^ Gartner, Richard (2016). Metadata: Shaping Knowledge from Antiquity to the Semantic Web. Springer. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-319-40893-4.

- ^ Romain, William F. (2019). "Lunar alignments at Ur: Entanglements with the Moon God Nanna". Journal of Skyscape Archaeology. 5 (2): 154. doi:10.1558/jsa.39074. ISSN 2055-3498.