Boston keratoprosthesis: Difference between revisions

MEDMOS |

KateWishing (talk | contribs) add history section |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

# A single center study from UC Davis of 30 Boston type I KPro procedures.<ref name="bradley"/> At an average follow-up of 19 months, retention rate of the device was 83%, 77% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 43%, high IOP in 27%, sterile vitritis complicated the postoperative course of 3% of eyes. The rate of infectious endophthalmitis in this study was 10%. |

# A single center study from UC Davis of 30 Boston type I KPro procedures.<ref name="bradley"/> At an average follow-up of 19 months, retention rate of the device was 83%, 77% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 43%, high IOP in 27%, sterile vitritis complicated the postoperative course of 3% of eyes. The rate of infectious endophthalmitis in this study was 10%. |

||

# A retrospective study of 36 Boston Type I KPro procedures from a single institution.<ref name="chew"/> At an average follow-up of 16 months, retention rate of the device was 100%, 83% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 65% and high IOP in 38%. Infectious endophthalmitis complicated 11% of eyes during the postoperative period. |

# A retrospective study of 36 Boston Type I KPro procedures from a single institution.<ref name="chew"/> At an average follow-up of 16 months, retention rate of the device was 100%, 83% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 65% and high IOP in 38%. Infectious endophthalmitis complicated 11% of eyes during the postoperative period. |

||

==History== |

|||

Boston ophthalmologist [[Claes Dohlman]] began developing the Boston keratoprosthesis in 1965,<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Prescott CR, Chodosh J | title = Ocular Surface Disease: Cornea, Conjunctiva and Tear Film | year = 2013 | page = 407 | publisher = Elsevier Health Sciences | isbn = 1455756237 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=C22EnmONhy4C&pg=PA407}}</ref> and refined it over the next decades.<ref name="copeland">{{cite book | vauthors = Prescott CR, Chodosh J | year = 2013 | title = Copeland and Afshari's Principles and Practice of Cornea | chapter = Boston Keratoprosthesis in the Management of Limbal Stem Cell Failure |publisher = JP Medical Ltd | page = 1194 | isbn = 9350901722 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=5WRrRMbSxbQC&pg=PA1194}}</ref> It was approved by the U.S. [[Food and Drug Administration]] in 1992.<ref name="copeland" /> Popularity increased in 2005, and by 2012, 8000 of the devices had been implanted by 400 different surgeons.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Colby K | year = 2014 | chapter = Future Directions for the Boston Keratoprosthesis | title = Keratoprostheses and Artificial Corneas | page = 181 | doi = 10.1007/978-3-642-55179-6_20}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 17:05, 13 October 2015

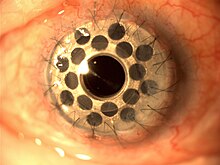

Boston keratoprosthesis (Boston KPro) is a collar button design keratoprosthesis or artificial cornea.[1] It is composed of a front plate with a stem, which houses the optical portion of the device, a back plate and a titanium locking c-ring.[2] It is available in type I and type II formats. The type I design is used much more frequently than the type II which is reserved for severe end stage dry eye conditions and is similar to the type I except it has a 2 mm anterior nub designed to penetrate through a tarsorrhaphy. The type I format will be discussed here as it is more commonly used.

The type I Kpro is available in single standard pseudophakic power or customized aphakic optic with an 8.5 mm diameter adult size or 7.0 mm diameter pediatric size back plate. The device is currently machined from medical grade polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) in Woburn, Massachusetts in the United States.[3] During implantation of the device, the device is assembled with a donor corneal graft positioned between the front and back plate which is then sutured into place in a similar fashion to penetrating keratoplasty (corneal transplantation).[4]

Indications

The Boston KPro is a treatment option for corneal disorders not amenable to standard penetrating keratoplasty (corneal transplantation) or corneal transplant. The Boston KPro is a proven primary treatment option for repeat graft failure,[5] herpetic keratitis,[6] aniridia [7] and many pediatric congenital corneal opacities including Peter's anomaly.[8] The device is also used to treat cicatrizing conditions including Stevens–Johnson syndrome [9] and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and also ocular burns.[10][11]

Complications

Most common postoperative complications in order of decreasing prevalence include retroprosthetic membrane (RPM), elevated intraocular pressure/glaucoma, infectious endophthalmitis, sterile vitritis, retina detachment (rare) and vitreous hemorrhage (rare).[12][13][14][15]

Postoperative management

- Indefinite placement of a bandage contact lens is needed to maintain adequate ocular surface hydration and prevent stromal melt, dellen formation, tissue melt and necrosis.[16]

- Indefinite daily topical antibiotic prophylaxis.[17]

- Lifelong topical steroids.[18]

- Close follow-up with an ophthalmologist to monitor for complications associated with the device. Although the surgical procedure is relatively straightforward for surgeons trained to perform corneal transplants, the follow-up required after KPro placement is lifelong.[18]

Design changes

- The addition of holes in the back plate. The device currently has 16 holes which provides a surface area of 18 mm2 for diffusion of nutritious aqueous to support the donor graft stroma and keratocytes.[19]

- In 2004, a titanium locking c-ring was added to prevent intraocular unscrewing of the device.[2]

- In 2007, a threadless design was introduced which simplified assembly and produced less damage to the donor graft when the device was assembled during the surgical procedure [19]

Outcomes

4 major studies have been completed to date showing outcomes with the type I Boston KPro:

- Multicenter Boston KPro Study is the largest published to date with 141 Boston type I keratoprosthesis procedures from 17 surgical sites by 39 different surgeons.[14] At an average follow-up of 8.5 months, retention rate of the device was 95%, 57% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 25%, high IOP in 15%, sterile vitritis complicated the postoperative course of 5% of eyes. Importantly, no cases of infectious endophthalmitis were reported in this large series.

- A large single surgeon series with 57 modern type I Boston KPro procedures from UCLA medical center.[12] At an average follow-up of 17 months, retention rate of the device was 84%, 75% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 25%, high IOP in 15%, sterile vitritis complicated the postoperative course of 5% of eyes. Postoperative complications included RPM in 44%, high IOP in 18%, sterile vitritis complicated the postoperative course of 10% of eyes. No cases of infectious enophthalmitis were reported in this series.

- A single center study from UC Davis of 30 Boston type I KPro procedures.[13] At an average follow-up of 19 months, retention rate of the device was 83%, 77% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 43%, high IOP in 27%, sterile vitritis complicated the postoperative course of 3% of eyes. The rate of infectious endophthalmitis in this study was 10%.

- A retrospective study of 36 Boston Type I KPro procedures from a single institution.[15] At an average follow-up of 16 months, retention rate of the device was 100%, 83% had BCVA ≥ 20/200. Postoperative complications included RPM in 65% and high IOP in 38%. Infectious endophthalmitis complicated 11% of eyes during the postoperative period.

History

Boston ophthalmologist Claes Dohlman began developing the Boston keratoprosthesis in 1965,[20] and refined it over the next decades.[21] It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1992.[21] Popularity increased in 2005, and by 2012, 8000 of the devices had been implanted by 400 different surgeons.[22]

References

- ^ Klufas MA , Starr CE. The Boston Keratoprosthesis: An update on recent advances. Cataract and Refractive Surgery Today. September 2009: 9(9).

- ^ a b Dohlman C, Harissi-Dagher M. The Boston Keratoprosthesis: A New Threadless Design. Digital Journal of Ophthalmology. 2007;13(3)

- ^ Khan B, Dudenhoefer EJ, Dohlman CH. Keratoprosthesis: an update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. Aug 2001;12(4):282-287

- ^ Todani A, Gupta P, Colby K. Type I Boston keratoprosthesis with cataract extraction and intraocular lens placement for visual rehabilitation of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: the "KPro Triple". Br J Ophthalmol. Jan 2009;93(1):119 - http://bjo.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/93/1/119/DC1

- ^ Ma JJ, Graney JM, Dohlman CH. Repeat penetrating keratoplasty versus the Boston keratoprosthesis in graft failure. Int Ophthalmol Clin. Fall 2005;45(4):49-59

- ^ Khan BF, Harissi-Dagher M, Pavan-Langston D, Aquavella JV, Dohlman CH. The Boston keratoprosthesis in herpetic keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. Jun 2007;125(6):745-749

- ^ Akpek EK, Harissi-Dagher M, Petrarca R, et al. Outcomes of Boston keratoprosthesis in aniridia: a retrospective multicenter study. Am J Ophthalmol. Aug 2007;144(2):227-231

- ^ Aquavella JV, Gearinger MD, Akpek EK, McCormick GJ. Pediatric keratoprosthesis. Ophthalmology. May 2007;114(5):989-994

- ^ Sayegh RR, Ang LP, Foster CS, Dohlman CH. The Boston keratoprosthesis in Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. Mar 2008;145(3):438-444

- ^ Tuft SJ, Shortt AJ. Surgical rehabilitation following severe ocular burns. Eye. Jan 23 2009

- ^ Harissi-Dagher M, Dohlman CH. The Boston Keratoprosthesis in severe ocular trauma. Can J Ophthalmol. Apr 2008;43(2):165-169

- ^ a b Aldave AJ, Kamal KM, Vo RC, Yu F. The Boston type I keratoprosthesis: improving outcomes and expanding indications. Ophthalmology. Apr 2009;116(4):640-651

- ^ a b Bradley JC, Hernandez EG, Schwab IR, Mannis MJ. Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis: the university of california davis experience. Cornea. Apr 2009;28(3):321-327

- ^ a b Zerbe BL, Belin MW, Ciolino JB. Results from the multicenter Boston Type 1 Keratoprosthesis Study. Ophthalmology. Oct 2006;113(10):1779

- ^ a b Chew HF, Ayres BD, Hammersmith KM, et al. Boston Keratoprosthesis Outcomes and Complications. Cornea. Aug 29 2009

- ^ Dohlman CH, Dudenhoefer EJ, Khan BF, Morneault S. Protection of the ocular surface after keratoprosthesis surgery: the role of soft contact lenses. Clao J. Apr 2002;28(2):72-74

- ^ Durand ML, Dohlman CH. Successful prevention of bacterial endophthalmitis in eyes with the Boston keratoprosthesis. Cornea. Sep 2009;28(8):896-901

- ^ a b Dohlman CH, Harissi-Dagher M, Khan BF, Sippel K, Aquavella JV, Graney JM. Introduction to the use of the Boston keratoprosthesis. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2006;1(1):41-48

- ^ a b Harissi-Dagher M, Khan BF, Schaumberg DA, Dohlman CH. Importance of nutrition to corneal grafts when used as a carrier of the Boston Keratoprosthesis. Cornea. Jun 2007;26(5):564-568

- ^ Prescott CR, Chodosh J (2013). Ocular Surface Disease: Cornea, Conjunctiva and Tear Film. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 407. ISBN 1455756237.

- ^ a b Prescott CR, Chodosh J (2013). "Boston Keratoprosthesis in the Management of Limbal Stem Cell Failure". Copeland and Afshari's Principles and Practice of Cornea. JP Medical Ltd. p. 1194. ISBN 9350901722.

- ^ Colby K (2014). "Future Directions for the Boston Keratoprosthesis". Keratoprostheses and Artificial Corneas. p. 181. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55179-6_20.

External links

- http://www.djo.harvard.edu/files/6425_1055.jpg

- http://www.djo.harvard.edu/files/6426_1055.jpg

- http://www.masseyeandear.org/specialties/ophthalmology/cornea-and-refractive-surgery/keratoprosthesis/

- http://bmctoday.net/crstoday/2009/09/article.asp?f=CRST0909_16.php

- http://eyewiki.aao.org/Boston_Keratoprosthesis_(KPro)