Cavitand: Difference between revisions

expanded on the content of cavitand summary |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) m Alter: doi, pmid. Add: year, doi, chapter-url, issue. Removed or converted URL. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were actually parameter name changes.| You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here.| Activated by User:Nemo bis | via #UCB_webform |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

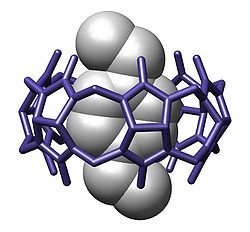

[[Image:Cucurbit-6-uril ActaCrystallB-Stru 1984 382.jpg|thumbnail|250px|A cavitand [[cucurbituril]] bound with a guest p-xylylenediammonium<ref>{{cite journal |last= Freeman |first= Wade A. |journal= [[Acta Crystallogr B]] |year= 1984 |pages= 382–387 |title= Structures of the ''p''-xylylenediammonium chloride and calcium hydrogensulfate adducts of the cavitand 'cucurbituril', C<sub>36</sub>H<sub>36</sub>N<sub>24</sub>O<sub>12</sub> |doi= 10.1107/S0108768184002354 |volume=40|url= http://journals.iucr.org/b/issues/1984/04/00/a23241/a23241.pdf }}</ref>]] |

[[Image:Cucurbit-6-uril ActaCrystallB-Stru 1984 382.jpg|thumbnail|250px|A cavitand [[cucurbituril]] bound with a guest p-xylylenediammonium<ref>{{cite journal |last= Freeman |first= Wade A. |journal= [[Acta Crystallogr B]] |year= 1984 |pages= 382–387 |title= Structures of the ''p''-xylylenediammonium chloride and calcium hydrogensulfate adducts of the cavitand 'cucurbituril', C<sub>36</sub>H<sub>36</sub>N<sub>24</sub>O<sub>12</sub> |doi= 10.1107/S0108768184002354 |volume=40|issue= 4 |url= http://journals.iucr.org/b/issues/1984/04/00/a23241/a23241.pdf }}</ref>]] |

||

A '''cavitand''' is a container shaped molecule.<ref>{{cite journal | author = D. J. Cram | title = Cavitands: organic hosts with enforced cavities | year = 1983 | journal = [[Science (journal)|Science]] | volume = 219 | issue = 4589 | pages = 1177–1183 | doi = 10.1126/science.219.4589.1177 | pmid = 17771285 | bibcode = 1983Sci...219.1177C }}</ref> The cavity of the cavitand allows it to engage in [[host–guest chemistry]] with guest molecules of a complementary shape and size. The original definition proposed by [[Donald J. Cram|Cram]] includes many classes of molecules: [[cyclodextrins]], [[calixarene]]s, [[pillararene]]s and [[cucurbituril]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Moran |first1=John R. |last2=Karbach |first2=Stefan |last3=Cram |first3=Donald J. |title=Cavitands: synthetic molecular vessels |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |date=October 1982 |volume=104 |issue=21 |pages=5826–5828 |doi=10.1021/ja00385a064}}</ref> However, modern usage in the field of [[supramolecular chemistry]] specifically refers to cavitands formed on a [[resorcinarene]] scaffold by bridging adjacent phenolic units.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jordan |first1=J. H. |last2=Gibb |first2=B. C. |editor1-last=Atwood |editor1-first=Jerry |title=Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II |date=2017 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=9780128031995 |pages=387–404 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124095472107899 |chapter=1.16 - Water-Soluble Cavitands☆}}</ref> The simplest bridging unit is methylene (-CH<sub>2</sub>-), although dimethylene (-(CH<sub>2</sub>)<sub>2</sub>-), trimethylene (-(CH<sub>2</sub>)<sub>3</sub>-), [[benzyl|benzal]], [[xylene|xylyl]], [[pyridine|pyridal]], [[quinoxaline|2,3-disubstituted-quinoxaline]], [[dinitrobenzene|''o''-dinitrobenzyl]], [[Dimethyldichlorosilane|dialkylsilydine]], and [[phosphonate]]s are known. Cavitands that have an extended aromatic bridging unit, or an extended cavity containing 3 rows of aromatic rings are referred to as deep-cavity cavitands and have broad applications in [[host-guest chemistry]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wishard |first1=A. |last2=Gibb |first2=B.C. |title=Calixarenes and beyond |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-319-31867-7 |pages= |

A '''cavitand''' is a container shaped molecule.<ref>{{cite journal | author = D. J. Cram | title = Cavitands: organic hosts with enforced cavities | year = 1983 | journal = [[Science (journal)|Science]] | volume = 219 | issue = 4589 | pages = 1177–1183 | doi = 10.1126/science.219.4589.1177 | pmid = 17771285 | bibcode = 1983Sci...219.1177C }}</ref> The cavity of the cavitand allows it to engage in [[host–guest chemistry]] with guest molecules of a complementary shape and size. The original definition proposed by [[Donald J. Cram|Cram]] includes many classes of molecules: [[cyclodextrins]], [[calixarene]]s, [[pillararene]]s and [[cucurbituril]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Moran |first1=John R. |last2=Karbach |first2=Stefan |last3=Cram |first3=Donald J. |title=Cavitands: synthetic molecular vessels |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |date=October 1982 |volume=104 |issue=21 |pages=5826–5828 |doi=10.1021/ja00385a064}}</ref> However, modern usage in the field of [[supramolecular chemistry]] specifically refers to cavitands formed on a [[resorcinarene]] scaffold by bridging adjacent phenolic units.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jordan |first1=J. H. |last2=Gibb |first2=B. C. |editor1-last=Atwood |editor1-first=Jerry |title=Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II |date=2017 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=9780128031995 |pages=387–404 |chapter-url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124095472107899 |chapter=1.16 - Water-Soluble Cavitands☆}}</ref> The simplest bridging unit is methylene (-CH<sub>2</sub>-), although dimethylene (-(CH<sub>2</sub>)<sub>2</sub>-), trimethylene (-(CH<sub>2</sub>)<sub>3</sub>-), [[benzyl|benzal]], [[xylene|xylyl]], [[pyridine|pyridal]], [[quinoxaline|2,3-disubstituted-quinoxaline]], [[dinitrobenzene|''o''-dinitrobenzyl]], [[Dimethyldichlorosilane|dialkylsilydine]], and [[phosphonate]]s are known. Cavitands that have an extended aromatic bridging unit, or an extended cavity containing 3 rows of aromatic rings are referred to as deep-cavity cavitands and have broad applications in [[host-guest chemistry]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wishard |first1=A. |last2=Gibb |first2=B.C. |title=Calixarenes and beyond |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-319-31867-7 |pages=195–234 |chapter=A chronology of cavitands|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7_9 |year=2016 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Cai |first1=X. |last2=Gibb |first2=B. C. |editor1-last=Atwood |editor1-first=Jerry |title=Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II |date=2017 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=9780128031995 |pages=75–82 |chapter-url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012409547212582X |chapter=6.04 - Deep-Cavity Cavitands in Self-Assembly}}</ref> These types of cavitands were extensively investigated by [[Julius Rebek|Rebek]], and [[Bruce C. Gibb|Gibb]], among others. |

||

== Applications of Cavitands == |

== Applications of Cavitands == |

||

Specific cavitands form the basis of rigid templates onto which ''[[De novo synthesis|de novo]]'' proteins can be chemically linked. This ''template assembled synthetic protein'' (TASP) structure provides a platform for the study of [[protein structure]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Tuchscherer|first=Gabriele|date=April 20, 1999|title=Extending the concept of template-assembled synthetic proteins|journal=J. Peptide Res.|volume=54|pages=185–194|doi=|pmid=|access-date=}}</ref> |

Specific cavitands form the basis of rigid templates onto which ''[[De novo synthesis|de novo]]'' proteins can be chemically linked. This ''template assembled synthetic protein'' (TASP) structure provides a platform for the study of [[protein structure]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Tuchscherer|first=Gabriele|date=April 20, 1999|title=Extending the concept of template-assembled synthetic proteins|journal=J. Peptide Res.|volume=54|issue=3|pages=185–194|doi=10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00120.x|pmid=10517155|access-date=}}</ref> |

||

Silicon surfaces [[Functional group|functionalized]] with tetraphosphonate cavitands have been used to singularly [[Molecular recognition|detect]] [[sarcosine]] in water and [[urine]] solutions.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Biavardi|first=Elisa|date=February 14, 2011|title=Exclusive recognition of sarcosine in water and urine by a cavitand-functionalized silicon surface |

Silicon surfaces [[Functional group|functionalized]] with tetraphosphonate cavitands have been used to singularly [[Molecular recognition|detect]] [[sarcosine]] in water and [[urine]] solutions.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Biavardi|first=Elisa|date=February 14, 2011|title=Exclusive recognition of sarcosine in water and urine by a cavitand-functionalized silicon surface|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|volume=109|issue=7|doi=10.1073/pnas.1112264109|pmid=22308349|pages=2263–2268|pmc=3289311|bibcode=2012PNAS..109.2263B}}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 23:04, 4 December 2019

A cavitand is a container shaped molecule.[2] The cavity of the cavitand allows it to engage in host–guest chemistry with guest molecules of a complementary shape and size. The original definition proposed by Cram includes many classes of molecules: cyclodextrins, calixarenes, pillararenes and cucurbiturils.[3] However, modern usage in the field of supramolecular chemistry specifically refers to cavitands formed on a resorcinarene scaffold by bridging adjacent phenolic units.[4] The simplest bridging unit is methylene (-CH2-), although dimethylene (-(CH2)2-), trimethylene (-(CH2)3-), benzal, xylyl, pyridal, 2,3-disubstituted-quinoxaline, o-dinitrobenzyl, dialkylsilydine, and phosphonates are known. Cavitands that have an extended aromatic bridging unit, or an extended cavity containing 3 rows of aromatic rings are referred to as deep-cavity cavitands and have broad applications in host-guest chemistry.[5][6] These types of cavitands were extensively investigated by Rebek, and Gibb, among others.

Applications of Cavitands

Specific cavitands form the basis of rigid templates onto which de novo proteins can be chemically linked. This template assembled synthetic protein (TASP) structure provides a platform for the study of protein structure.[7]

Silicon surfaces functionalized with tetraphosphonate cavitands have been used to singularly detect sarcosine in water and urine solutions.[8]

See also

References

- ^ Freeman, Wade A. (1984). "Structures of the p-xylylenediammonium chloride and calcium hydrogensulfate adducts of the cavitand 'cucurbituril', C36H36N24O12" (PDF). Acta Crystallogr B. 40 (4): 382–387. doi:10.1107/S0108768184002354.

- ^ D. J. Cram (1983). "Cavitands: organic hosts with enforced cavities". Science. 219 (4589): 1177–1183. Bibcode:1983Sci...219.1177C. doi:10.1126/science.219.4589.1177. PMID 17771285.

- ^ Moran, John R.; Karbach, Stefan; Cram, Donald J. (October 1982). "Cavitands: synthetic molecular vessels". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (21): 5826–5828. doi:10.1021/ja00385a064.

- ^ Jordan, J. H.; Gibb, B. C. (2017). "1.16 - Water-Soluble Cavitands☆". In Atwood, Jerry (ed.). Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II. Elsevier. pp. 387–404. ISBN 9780128031995.

- ^ Wishard, A.; Gibb, B.C. (2016). "A chronology of cavitands". Calixarenes and beyond. Springer. pp. 195–234. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7_9. ISBN 978-3-319-31867-7.

- ^ Cai, X.; Gibb, B. C. (2017). "6.04 - Deep-Cavity Cavitands in Self-Assembly". In Atwood, Jerry (ed.). Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II. Elsevier. pp. 75–82. ISBN 9780128031995.

- ^ Tuchscherer, Gabriele (April 20, 1999). "Extending the concept of template-assembled synthetic proteins". J. Peptide Res. 54 (3): 185–194. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00120.x. PMID 10517155.

- ^ Biavardi, Elisa (February 14, 2011). "Exclusive recognition of sarcosine in water and urine by a cavitand-functionalized silicon surface". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (7): 2263–2268. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.2263B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112264109. PMC 3289311. PMID 22308349.