Diathesis–stress model: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

The diathesis, or predisposition, interacts with the individual's subsequent [[Stress (psychology)|stress]] response. Stress is a life event or series of events that disrupts a person's psychological equilibrium and may catalyze the development of a disorder.<ref name="Oatleyb" /> Thus the diathesis–stress model serves to explore how biological or genetic traits (''diatheses'') interact with environmental influences (''stressors'') to produce disorders such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.<ref name="PreventionAction">Prevention Action. ''Diathesis-stress models'' Retrieved from http://www.preventionaction.org/reference/diathesis-stress-models {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120603201839/http://www.preventionaction.org/reference/diathesis-stress-models |date=2012-06-03 }}</ref> |

The diathesis, or predisposition, interacts with the individual's subsequent [[Stress (psychology)|stress]] response. Stress is a life event or series of events that disrupts a person's psychological equilibrium and may catalyze the development of a disorder.<ref name="Oatleyb" /> Thus the diathesis–stress model serves to explore how biological or genetic traits (''diatheses'') interact with environmental influences (''stressors'') to produce disorders such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.<ref name="PreventionAction">Prevention Action. ''Diathesis-stress models'' Retrieved from http://www.preventionaction.org/reference/diathesis-stress-models {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120603201839/http://www.preventionaction.org/reference/diathesis-stress-models |date=2012-06-03 }}</ref> |

||

The diathesis–stress model asserts that if the combination of the predisposition and the stress exceeds a threshold, the person will develop a [[psychological disorder|disorder]].<ref name="Lazarus">{{cite journal | |

The diathesis–stress model asserts that if the combination of the predisposition and the stress exceeds a threshold, the person will develop a [[psychological disorder|disorder]].<ref name="Lazarus">{{cite journal |last1=Lazarus |first1=R. S. |title=From Psychological Stress to the Emotions: A History of Changing Outlooks |journal=Annual Review of Psychology |date=January 1993 |volume=44 |issue=1 |pages=1–22 |doi=10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245 |pmid=8434890 }}</ref> |

||

The use of the term ''diathesis'' in medicine and in the specialty of psychiatry dates back to the 1800s; however, the diathesis–stress model was not introduced and used to describe the development of [[psychopathology]] until it was applied to explaining [[schizophrenia]] in the 1960s by [[Paul Meehl]].<ref>{{cite journal | |

The use of the term ''diathesis'' in medicine and in the specialty of psychiatry dates back to the 1800s; however, the diathesis–stress model was not introduced and used to describe the development of [[psychopathology]] until it was applied to explaining [[schizophrenia]] in the 1960s by [[Paul Meehl]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Meehl |first1=Paul E. |title=Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. |journal=American Psychologist |date=1962 |volume=17 |issue=12 |pages=827–838 |doi=10.1037/h0041029 |citeseerx=10.1.1.462.2509 }}</ref><ref name="Ingram"/> |

||

The diathesis–stress model is used in many fields of [[psychology]], specifically for studying the development of psychopathology.<ref name="Sigelman">Sigelman, C. K. & Rider, E. A. (2009). [https://books.google.com/books?id=8smBuRecmDsC&pg=PT656&dq=Life-span+human+development+6th+ed&hl=en&sa=X&ei=P1_HUJqFG8iy0AH5ioGoAw&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAA Developmental psychopathology.] ''Life-span human development'' (6th ed.) (pp. 468-495). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.</ref> It is useful for the purposes of understanding the interplay of [[nature and nurture]] in the susceptibility to [[psychological disorders]] throughout the lifespan.<ref name="Sigelman"/> Diathesis–stress models can also assist in determining who will develop a disorder and who will not.<ref name="Oatleya">Oatley, K., Keltner, D., & Jenkins, J. M. (2006a). "Emotions and mental health in adulthood." ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=RGHghPqIO_8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Understanding+emotions+2nd+ed&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rl_HUMGGB6jh0wGwyoDYBg&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA Understanding Emotions]'' (2nd ed.) (pp. 353-383). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.</ref> For example, in the context of [[Depression (mood)|depression]], the diathesis–stress model can help explain why Person A may become depressed while Person B does not, even when exposed to the same stressors.<ref name="Sigelman"/> More recently, the diathesis–stress model has been used to explain why some individuals are more at risk for developing a disorder than others.<ref name="Gazelle">{{cite journal | |

The diathesis–stress model is used in many fields of [[psychology]], specifically for studying the development of psychopathology.<ref name="Sigelman">Sigelman, C. K. & Rider, E. A. (2009). [https://books.google.com/books?id=8smBuRecmDsC&pg=PT656&dq=Life-span+human+development+6th+ed&hl=en&sa=X&ei=P1_HUJqFG8iy0AH5ioGoAw&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAA Developmental psychopathology.] ''Life-span human development'' (6th ed.) (pp. 468-495). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.</ref> It is useful for the purposes of understanding the interplay of [[nature and nurture]] in the susceptibility to [[psychological disorders]] throughout the lifespan.<ref name="Sigelman"/> Diathesis–stress models can also assist in determining who will develop a disorder and who will not.<ref name="Oatleya">Oatley, K., Keltner, D., & Jenkins, J. M. (2006a). "Emotions and mental health in adulthood." ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=RGHghPqIO_8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Understanding+emotions+2nd+ed&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rl_HUMGGB6jh0wGwyoDYBg&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA Understanding Emotions]'' (2nd ed.) (pp. 353-383). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.</ref> For example, in the context of [[Depression (mood)|depression]], the diathesis–stress model can help explain why Person A may become depressed while Person B does not, even when exposed to the same stressors.<ref name="Sigelman"/> More recently, the diathesis–stress model has been used to explain why some individuals are more at risk for developing a disorder than others.<ref name="Gazelle">{{cite journal |last1=Gazelle |first1=Heidi |last2=Ladd |first2=Gary W. |title=Anxious Solitude and Peer Exclusion: A Diathesis-Stress Model of Internalizing Trajectories in Childhood |journal=Child Development |date=February 2003 |volume=74 |issue=1 |pages=257–278 |doi=10.1111/1467-8624.00534 }}</ref> For example, children who have a family history of depression are generally more vulnerable to developing a depressive disorder themselves. A child who has a family history of depression and who has been exposed to a particular stressor, such as [[peer rejection|exclusion or rejection by his or her peers]], would be more likely to develop depression than a child with a family history of depression that has an otherwise positive social network of peers.<ref name="Gazelle"/> |

||

The diathesis–stress model has also served as useful in explaining other poor (but non-clinical) developmental outcomes. |

The diathesis–stress model has also served as useful in explaining other poor (but non-clinical) developmental outcomes. |

||

| Line 15: | Line 16: | ||

The term diathesis is synonymous with [[vulnerability]], and variants such as "vulnerability-stress" are common within psychology.<ref name="Sigelman"/> A [[vulnerability]] makes it more or less likely that an individual will succumb to the development of [[psychopathology]] if a certain stress is encountered.<ref name="Ingram"/> Diatheses are considered inherent within the individual and are typically conceptualized as being stable, but not unchangeable, over the lifespan.<ref name="Oatleyb">Oatley, K., Keltner, D. & Jenkins, J. M. (2006b). "Emotions and mental health in childhood."''[https://books.google.com/books?id=RGHghPqIO_8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Understanding+emotions+2nd+ed&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rl_HUMGGB6jh0wGwyoDYBg&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA Understanding emotions]'' (2nd ed.) (pp. 321-351). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.</ref><ref name="Ormel2013"/> They are also often considered latent (i.e. dormant), because they are harder to recognize unless provoked by stressors.<ref name="Ingram"/> |

The term diathesis is synonymous with [[vulnerability]], and variants such as "vulnerability-stress" are common within psychology.<ref name="Sigelman"/> A [[vulnerability]] makes it more or less likely that an individual will succumb to the development of [[psychopathology]] if a certain stress is encountered.<ref name="Ingram"/> Diatheses are considered inherent within the individual and are typically conceptualized as being stable, but not unchangeable, over the lifespan.<ref name="Oatleyb">Oatley, K., Keltner, D. & Jenkins, J. M. (2006b). "Emotions and mental health in childhood."''[https://books.google.com/books?id=RGHghPqIO_8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Understanding+emotions+2nd+ed&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rl_HUMGGB6jh0wGwyoDYBg&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA Understanding emotions]'' (2nd ed.) (pp. 321-351). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.</ref><ref name="Ormel2013"/> They are also often considered latent (i.e. dormant), because they are harder to recognize unless provoked by stressors.<ref name="Ingram"/> |

||

Diatheses are understood to include [[Heredity|genetic]], [[biological]], [[physiological]], [[cognitive]], and [[personality]]-related factors.<ref name="Sigelman"/> Some examples of diatheses include genetic factors, such as abnormalities in some genes or variations in multiple genes that interact to increase vulnerability. Other diatheses include early life experiences such as the loss of a parent,<ref name="Oatleya"/> or high neuroticism.<ref name="NeuroticismMA">{{cite journal | |

Diatheses are understood to include [[Heredity|genetic]], [[biological]], [[physiological]], [[cognitive]], and [[personality]]-related factors.<ref name="Sigelman"/> Some examples of diatheses include genetic factors, such as abnormalities in some genes or variations in multiple genes that interact to increase vulnerability. Other diatheses include early life experiences such as the loss of a parent,<ref name="Oatleya"/> or high neuroticism.<ref name="NeuroticismMA">{{cite journal |last1=Jeronimus |first1=B. F. |last2=Kotov |first2=R. |last3=Riese |first3=H. |last4=Ormel |first4=J. |title=Neuroticism's prospective association with mental disorders halves after adjustment for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, but the adjusted association hardly decays with time: a meta-analysis on 59 longitudinal/prospective studies with 443 313 participants |journal=Psychological Medicine |date=15 August 2016 |volume=46 |issue=14 |pages=2883–2906 |doi=10.1017/S0033291716001653 |pmid=27523506 |url=https://zenodo.org/record/895885 }}</ref> Diatheses can also be conceptualized as situational factors, such as low [[socio-economic status]] or having a parent with depression. |

||

==Stress== |

==Stress== |

||

Stress can be conceptualized as a life event that disrupts the equilibrium of a person's life.<ref name="Oatleyb"/><ref name="Jeronimus2013">{{cite journal| |

Stress can be conceptualized as a life event that disrupts the equilibrium of a person's life.<ref name="Oatleyb"/><ref name="Jeronimus2013">{{cite journal |last1=Jeronimus |first1=B. F. |last2=Ormel |first2=J. |last3=Aleman |first3=A. |last4=Penninx |first4=B. W. J. H. |last5=Riese |first5=H. |title=Negative and positive life events are associated with small but lasting change in neuroticism |journal=Psychological Medicine |date=15 February 2013 |volume=43 |issue=11 |pages=2403–2415 |doi=10.1017/S0033291713000159 |pmid=23410535 }}</ref> For instance, a person may be vulnerable to become depressed, but will not develop depression unless he or she is exposed to a specific stress, which may trigger a depressive disorder.<ref name="Nolen">Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2008). "Suicide". ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=wYIsQAAACAAJ&dq=nolen-hoeksema+abnormal+psychology&hl=en&sa=X&ei=dHrHUIT4Iee80QHY1YDgCg&ved=0CDgQ6AEwAA Abnormal Psychology]'' (4th ed.) (pp. 350-373). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.</ref> Stressors can take the form of a discrete event, such the [[divorce]] of parents or a [[death]] in the family, or can be more chronic factors such as having a [[chronic illness|long-term illness]], or ongoing marital problems.<ref name="Oatleya"/> Stresses can also be related to more daily hassles such as school assignment deadlines. This also parallels the popular (and engineering) usage of stress, but note that some literature defines stress as the [[stress (biology)|response]] to stressors, especially where usage in biology influences neuroscience. |

||

It has been long recognized that stress plays a significant role in understanding how psychopathology develops in individuals.<ref name="Monroe">{{cite journal | |

It has been long recognized that stress plays a significant role in understanding how psychopathology develops in individuals.<ref name="Monroe">{{cite journal |last1=Monroe |first1=Scott M. |last2=Simons |first2=Anne D. |title=Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. |journal=Psychological Bulletin |date=1991 |volume=110 |issue=3 |pages=406–425 |doi=10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406 |pmid=1758917 }}</ref> However, psychologists have also identified that not all individuals who are stressed, or go through stressful life events, develop a psychological disorder. To understand this, theorists and researchers explored other factors that affect the development of a disorder <ref name="Monroe"/> and proposed that some individuals under stress develop a disorder and others do not. As such, some individuals are more vulnerable than others to develop a disorder once stress has been introduced.<ref name="Ingram"/> This led to the formulation of the diathesis–stress model. |

||

==Evidence== |

==Evidence== |

||

Stress is a [[mast cell]] activator<ref> |

Stress is a [[mast cell]] activator.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Baldwin |first1=AL |title=Mast cell activation by stress |journal=Methods in Molecular Bology |date=2006 |volume=315 |pages=349-60 |doi=10.1385/1-59259-967-2:349 |pmid=16110169 }}</ref> Mast cells are long-lived tissue-resident cells with an important role in many inflammatory settings including host defence to parasitic infection and in allergic reactions.<ref>https://www.immunology.org/public-information/bitesized-immunology/cells/mast-cells</ref> |

||

A 2019 study concluded "We provide human evidence that children exposed to prenatal stress may experience resilience driven by epigenome-wide interactions."<ref> |

A 2019 study concluded "We provide human evidence that children exposed to prenatal stress may experience resilience driven by epigenome-wide interactions."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Serpeloni |first1=Fernanda |last2=Radtke |first2=Karl M. |last3=Hecker |first3=Tobias |last4=Sill |first4=Johanna |last5=Vukojevic |first5=Vanja |last6=Assis |first6=Simone G. de |last7=Schauer |first7=Maggie |last8=Elbert |first8=Thomas |last9=Nätt |first9=Daniel |title=Does Prenatal Stress Shape Postnatal Resilience? – An Epigenome-Wide Study on Violence and Mental Health in Humans |journal=Frontiers in Genetics |date=16 April 2019 |volume=10 |doi=10.3389/fgene.2019.00269 }}</ref> |

||

Carriers of congenital adrenal hyperplasia have a predeposition to stress<ref> |

Carriers of congenital adrenal hyperplasia have a predeposition to stress,<ref>{{cite journal |title=Psychological vulnerability to stress in carriers of congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency |journal=HORMONES |date=12 May 2017 |volume=16 |issue=1 |doi=10.14310/horm.2002.1718 }}</ref> due to the unique nature of this gene.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Concolino |first1=Paola |title=Issues with the Detection of Large Genomic Rearrangements in Molecular Diagnosis of 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency |journal=Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy |date=17 July 2019 |volume=23 |issue=5 |pages=563–567 |doi=10.1007/s40291-019-00415-z |pmid=31317337 }}</ref> True rates of prevalance are not known but mutations are estimated in 20-30% of the population. |

||

Ancestral Stress Alters Lifetime Mental Health Trajectories and Cortical Neuromorphology via Epigenetic Regulation<ref> |

Ancestral Stress Alters Lifetime Mental Health Trajectories and Cortical Neuromorphology via Epigenetic Regulation.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ambeskovic |first1=Mirela |last2=Babenko |first2=Olena |last3=Ilnytskyy |first3=Yaroslav |last4=Kovalchuk |first4=Igor |last5=Kolb |first5=Bryan |last6=Metz |first6=Gerlinde A. S. |title=Ancestral Stress Alters Lifetime Mental Health Trajectories and Cortical Neuromorphology via Epigenetic Regulation |journal=Scientific Reports |date=23 April 2019 |volume=9 |issue=1 |doi=10.1038/s41598-019-42691-z }}</ref> |

||

Psychological distress is a known feature of generalized joint hypermobility (gJHM), as well as of its most common syndromic presentation, namely Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type (a.k.a. joint hypermobility syndrome - JHS/EDS-HT), and significantly contributes to the quality of life of affected individuals. Most published articles dealt with the link between gJHM (or JHS/EDS-HT) and anxiety-related conditions, and a novel generation of studies is emerging aimed at investigating the psychopathologic background of such an association. In this paper, literature review was carried out with a semi-systematic approach spanning the entire spectrum of psychopathological findings in gJHM and JHS/EDS-HT. Interestingly, in addition to the confirmation of a tight link between anxiety and gJHM, preliminary connections with depression, attention deficit (and hyperactivity) disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were also found. Few papers investigated the relationship with schizophrenia with contrasting results. The mind-body connections hypothesized on the basis of available data were discussed with focus on somatotype, presumed psychopathology, and involvement of the extracellular matrix in the central nervous system. The hypothesis of positive Beighton score and alteration of interoceptive/proprioceptive/body awareness as possible endophenotypes in families with symptomatic gJHM or JHS/EDS-HT is also suggested. Concluding remarks addressed the implications of the psychopathological features of gJHM and JHS/EDS-HT in clinical practice.<ref> |

Psychological distress is a known feature of generalized joint hypermobility (gJHM), as well as of its most common syndromic presentation, namely Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type (a.k.a. joint hypermobility syndrome - JHS/EDS-HT), and significantly contributes to the quality of life of affected individuals. Most published articles dealt with the link between gJHM (or JHS/EDS-HT) and anxiety-related conditions, and a novel generation of studies is emerging aimed at investigating the psychopathologic background of such an association. In this paper, literature review was carried out with a semi-systematic approach spanning the entire spectrum of psychopathological findings in gJHM and JHS/EDS-HT. Interestingly, in addition to the confirmation of a tight link between anxiety and gJHM, preliminary connections with depression, attention deficit (and hyperactivity) disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were also found. Few papers investigated the relationship with schizophrenia with contrasting results. The mind-body connections hypothesized on the basis of available data were discussed with focus on somatotype, presumed psychopathology, and involvement of the extracellular matrix in the central nervous system. The hypothesis of positive Beighton score and alteration of interoceptive/proprioceptive/body awareness as possible endophenotypes in families with symptomatic gJHM or JHS/EDS-HT is also suggested. Concluding remarks addressed the implications of the psychopathological features of gJHM and JHS/EDS-HT in clinical practice.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sinibaldi |first1=Lorenzo |last2=Ursini |first2=Gianluca |last3=Castori |first3=Marco |title=Psychopathological manifestations of joint hypermobility and joint hypermobility syndrome/ Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type: The link between connective tissue and psychological distress revised |journal=American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics |date=March 2015 |volume=169 |issue=1 |pages=97–106 |doi=10.1002/ajmg.c.31430 |pmid=25821094 }}</ref> |

||

Early life stress interactions with the epigenome: potential mechanisms driving vulnerability towards psychiatric illness<ref> |

Early life stress interactions with the epigenome: potential mechanisms driving vulnerability towards psychiatric illness.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lewis |first1=Candace Renee |last2=Olive |first2=Michael Foster |title=Early life stress interactions with the epigenome: potential mechanisms driving vulnerability towards psychiatric illness |journal=Behavioural pharmacology |date=2014 |volume=25 |issue=5 0 6 |pages=341–351 |doi=10.1097/FBP.0000000000000057 |pmid=25003947 |pmc=4119485 }}</ref> |

||

==Protective factors== |

==Protective factors== |

||

| Line 51: | Line 52: | ||

Windows of vulnerability for developing specific psychopathologies are believed to exist at different points of the lifespan. Moreover, different diatheses and stressors are implicated in different disorders. For example, breakups and other severe or traumatic life stressors are implicated in the development of depression. Stressful events can also trigger the manic phase of [[bipolar disorder]] and stressful events can then prevent recovery and trigger relapse. Having a genetic disposition for becoming addicted and later engaging in [[binge drinking]] in college are implicated in the development of [[alcoholism]]. A family history of [[schizophrenia]] combined with the stressor of being raised in a dysfunctional family raises the risk of developing schizophrenia.<ref name="Barlow">Barlow, D. H. & Durand, V. M. (2009). ''[https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=yITxaqlS_yMC&oi=fnd&pg=PT6&dq=Abnormal+psychology:+An+integrative+approach&ots=OwHqAzXsvB&sig=axcuq5OQ9jOIZJNcplsKQUsiZgc Abnormal psychology: An integrative approach.]'' Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.</ref> |

Windows of vulnerability for developing specific psychopathologies are believed to exist at different points of the lifespan. Moreover, different diatheses and stressors are implicated in different disorders. For example, breakups and other severe or traumatic life stressors are implicated in the development of depression. Stressful events can also trigger the manic phase of [[bipolar disorder]] and stressful events can then prevent recovery and trigger relapse. Having a genetic disposition for becoming addicted and later engaging in [[binge drinking]] in college are implicated in the development of [[alcoholism]]. A family history of [[schizophrenia]] combined with the stressor of being raised in a dysfunctional family raises the risk of developing schizophrenia.<ref name="Barlow">Barlow, D. H. & Durand, V. M. (2009). ''[https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=yITxaqlS_yMC&oi=fnd&pg=PT6&dq=Abnormal+psychology:+An+integrative+approach&ots=OwHqAzXsvB&sig=axcuq5OQ9jOIZJNcplsKQUsiZgc Abnormal psychology: An integrative approach.]'' Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.</ref> |

||

Diathesis–stress models are often conceptualized as multi-causal developmental models, which propose that multiple [[risk factors]] over the course of development interact with stressors and protective factors contributing to normal development or psychopathology.<ref name="Masten">{{cite journal | |

Diathesis–stress models are often conceptualized as multi-causal developmental models, which propose that multiple [[risk factors]] over the course of development interact with stressors and protective factors contributing to normal development or psychopathology.<ref name="Masten">{{cite journal |last1=Masten |first1=Ann S. |title=Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. |journal=American Psychologist |date=2001 |volume=56 |issue=3 |pages=227–238 |doi=10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227 |pmid=11315249 }}</ref> For example, a child with a family history of depression likely has a genetic vulnerability to depressive disorder. This child has also been exposed to environmental factors associated with parental depression that increase his or her vulnerability to developing depression as well. Protective factors, such as strong peer network, involvement in extracurricular activities, and a positive relationship with the non-depressed parent, interact with the child's vulnerabilities in determining the progression to psychopathology versus normative development.<ref name="Cummings">Cummings, M. E., Davies, P. T., & Campbell, S. B. (2000). ''[https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=5SyyeX-yVbAC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Developmental+psychopathology+and+family+process:+Theory,+research,+and+clinical+implications&ots=qywEE0b9c1&sig=YQ92AoXpIsmgYc2-cVCx1Gsal30 Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications.]'' New York, NY: The Guilford Press.</ref> |

||

Some theories have branched from the diathesis–stress model, such as the [[differential susceptibility hypothesis]], which extends the model to include a vulnerability to positive environments as well as negative environments or stress.<ref name="Belsky">{{cite journal | |

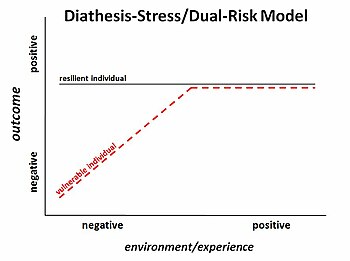

Some theories have branched from the diathesis–stress model, such as the [[differential susceptibility hypothesis]], which extends the model to include a vulnerability to positive environments as well as negative environments or stress.<ref name="Belsky">{{cite journal |last1=Belsky |first1=Jay |last2=Pluess |first2=Michael |title=Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. |journal=Psychological Bulletin |date=2009 |volume=135 |issue=6 |pages=885–908 |doi=10.1037/a0017376 |pmid=19883141 }}</ref> A person could have a biological vulnerability that when combined with a stressor could lead to psychopathology (diathesis–stress model); but that same person with a biological vulnerability, if exposed to a particularly positive environment, could have better outcomes than a person without the vulnerability.<ref name="Belsky"/> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 14:51, 18 February 2020

The diathesis–stress model is a psychological theory that attempts to explain a disorder, or its trajectory, as the result of an interaction between a predispositional vulnerability and a stress caused by life experiences. The term diathesis derives from the Greek term (διάθεσις) for a predisposition, or sensibility. A diathesis can take the form of genetic, psychological, biological, or situational factors.[1] A large range of differences exists among individuals' vulnerabilities to the development of a disorder.[1][2]

The diathesis, or predisposition, interacts with the individual's subsequent stress response. Stress is a life event or series of events that disrupts a person's psychological equilibrium and may catalyze the development of a disorder.[3] Thus the diathesis–stress model serves to explore how biological or genetic traits (diatheses) interact with environmental influences (stressors) to produce disorders such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.[4]

The diathesis–stress model asserts that if the combination of the predisposition and the stress exceeds a threshold, the person will develop a disorder.[5]

The use of the term diathesis in medicine and in the specialty of psychiatry dates back to the 1800s; however, the diathesis–stress model was not introduced and used to describe the development of psychopathology until it was applied to explaining schizophrenia in the 1960s by Paul Meehl.[6][1]

The diathesis–stress model is used in many fields of psychology, specifically for studying the development of psychopathology.[7] It is useful for the purposes of understanding the interplay of nature and nurture in the susceptibility to psychological disorders throughout the lifespan.[7] Diathesis–stress models can also assist in determining who will develop a disorder and who will not.[8] For example, in the context of depression, the diathesis–stress model can help explain why Person A may become depressed while Person B does not, even when exposed to the same stressors.[7] More recently, the diathesis–stress model has been used to explain why some individuals are more at risk for developing a disorder than others.[9] For example, children who have a family history of depression are generally more vulnerable to developing a depressive disorder themselves. A child who has a family history of depression and who has been exposed to a particular stressor, such as exclusion or rejection by his or her peers, would be more likely to develop depression than a child with a family history of depression that has an otherwise positive social network of peers.[9]

The diathesis–stress model has also served as useful in explaining other poor (but non-clinical) developmental outcomes.

Protective factors, such as positive social networks or high self-esteem, can counteract the effects of stressors and prevent or curb the effects of disorder.[10] Many psychological disorders have a window of vulnerability, during which time an individual is more likely to develop disorder than others.[11] Diathesis–stress models are often conceptualized as multi-causal developmental models, which propose that multiple risk factors over the course of development interact with stressors and protective factors contributing to normal development or psychopathology.[12] The differential susceptibility hypothesis is a recent theory that has stemmed from the diathesis–stress model.[13]

Diathesis

The term diathesis is synonymous with vulnerability, and variants such as "vulnerability-stress" are common within psychology.[7] A vulnerability makes it more or less likely that an individual will succumb to the development of psychopathology if a certain stress is encountered.[1] Diatheses are considered inherent within the individual and are typically conceptualized as being stable, but not unchangeable, over the lifespan.[3][2] They are also often considered latent (i.e. dormant), because they are harder to recognize unless provoked by stressors.[1]

Diatheses are understood to include genetic, biological, physiological, cognitive, and personality-related factors.[7] Some examples of diatheses include genetic factors, such as abnormalities in some genes or variations in multiple genes that interact to increase vulnerability. Other diatheses include early life experiences such as the loss of a parent,[8] or high neuroticism.[14] Diatheses can also be conceptualized as situational factors, such as low socio-economic status or having a parent with depression.

Stress

Stress can be conceptualized as a life event that disrupts the equilibrium of a person's life.[3][15] For instance, a person may be vulnerable to become depressed, but will not develop depression unless he or she is exposed to a specific stress, which may trigger a depressive disorder.[16] Stressors can take the form of a discrete event, such the divorce of parents or a death in the family, or can be more chronic factors such as having a long-term illness, or ongoing marital problems.[8] Stresses can also be related to more daily hassles such as school assignment deadlines. This also parallels the popular (and engineering) usage of stress, but note that some literature defines stress as the response to stressors, especially where usage in biology influences neuroscience.

It has been long recognized that stress plays a significant role in understanding how psychopathology develops in individuals.[17] However, psychologists have also identified that not all individuals who are stressed, or go through stressful life events, develop a psychological disorder. To understand this, theorists and researchers explored other factors that affect the development of a disorder [17] and proposed that some individuals under stress develop a disorder and others do not. As such, some individuals are more vulnerable than others to develop a disorder once stress has been introduced.[1] This led to the formulation of the diathesis–stress model.

Evidence

Stress is a mast cell activator.[18] Mast cells are long-lived tissue-resident cells with an important role in many inflammatory settings including host defence to parasitic infection and in allergic reactions.[19]

A 2019 study concluded "We provide human evidence that children exposed to prenatal stress may experience resilience driven by epigenome-wide interactions."[20]

Carriers of congenital adrenal hyperplasia have a predeposition to stress,[21] due to the unique nature of this gene.[22] True rates of prevalance are not known but mutations are estimated in 20-30% of the population.

Ancestral Stress Alters Lifetime Mental Health Trajectories and Cortical Neuromorphology via Epigenetic Regulation.[23]

Psychological distress is a known feature of generalized joint hypermobility (gJHM), as well as of its most common syndromic presentation, namely Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type (a.k.a. joint hypermobility syndrome - JHS/EDS-HT), and significantly contributes to the quality of life of affected individuals. Most published articles dealt with the link between gJHM (or JHS/EDS-HT) and anxiety-related conditions, and a novel generation of studies is emerging aimed at investigating the psychopathologic background of such an association. In this paper, literature review was carried out with a semi-systematic approach spanning the entire spectrum of psychopathological findings in gJHM and JHS/EDS-HT. Interestingly, in addition to the confirmation of a tight link between anxiety and gJHM, preliminary connections with depression, attention deficit (and hyperactivity) disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were also found. Few papers investigated the relationship with schizophrenia with contrasting results. The mind-body connections hypothesized on the basis of available data were discussed with focus on somatotype, presumed psychopathology, and involvement of the extracellular matrix in the central nervous system. The hypothesis of positive Beighton score and alteration of interoceptive/proprioceptive/body awareness as possible endophenotypes in families with symptomatic gJHM or JHS/EDS-HT is also suggested. Concluding remarks addressed the implications of the psychopathological features of gJHM and JHS/EDS-HT in clinical practice.[24]

Early life stress interactions with the epigenome: potential mechanisms driving vulnerability towards psychiatric illness.[25]

Protective factors

Protective factors, while not an inherent component of the diathesis–stress model, are of importance when considering the interaction of diatheses and stress. Protective factors can mitigate or provide a buffer against the effects of major stressors by providing an individual with developmentally adaptive outlets to deal with stress.[10] Examples of protective factors include a positive parent-child attachment relationship, a supportive peer network, and individual social and emotional competence.[10]

Throughout the lifespan

Many models of psychopathology generally suggest that all people have some level of vulnerability towards certain mental disorders, but posit a large range of individual differences in the point at which a person will develop a certain disorder.[1] For example, an individual with personality traits that tend to promote relationships such as extroversion and agreeableness may engender strong social support, which may later serve as a protective factor when experiencing stressors or losses that may delay or prevent the development of depression. Conversely, an individual who finds it difficult to develop and maintain supportive relationships may be more vulnerable to developing depression following a job loss because they do not have protective social support. An individual's threshold is determined by the interaction of diatheses and stress.[3]

Windows of vulnerability for developing specific psychopathologies are believed to exist at different points of the lifespan. Moreover, different diatheses and stressors are implicated in different disorders. For example, breakups and other severe or traumatic life stressors are implicated in the development of depression. Stressful events can also trigger the manic phase of bipolar disorder and stressful events can then prevent recovery and trigger relapse. Having a genetic disposition for becoming addicted and later engaging in binge drinking in college are implicated in the development of alcoholism. A family history of schizophrenia combined with the stressor of being raised in a dysfunctional family raises the risk of developing schizophrenia.[11]

Diathesis–stress models are often conceptualized as multi-causal developmental models, which propose that multiple risk factors over the course of development interact with stressors and protective factors contributing to normal development or psychopathology.[12] For example, a child with a family history of depression likely has a genetic vulnerability to depressive disorder. This child has also been exposed to environmental factors associated with parental depression that increase his or her vulnerability to developing depression as well. Protective factors, such as strong peer network, involvement in extracurricular activities, and a positive relationship with the non-depressed parent, interact with the child's vulnerabilities in determining the progression to psychopathology versus normative development.[26]

Some theories have branched from the diathesis–stress model, such as the differential susceptibility hypothesis, which extends the model to include a vulnerability to positive environments as well as negative environments or stress.[13] A person could have a biological vulnerability that when combined with a stressor could lead to psychopathology (diathesis–stress model); but that same person with a biological vulnerability, if exposed to a particularly positive environment, could have better outcomes than a person without the vulnerability.[13]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Ingram, R. E. & Luxton, D. D. (2005). "Vulnerability-Stress Models." In B.L. Hankin & J. R. Z. Abela (Eds.), Development of Psychopathology: A vulnerability stress perspective (pp. 32-46). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- ^ a b Ormel J.; Jeronimus, B.F.; Kotov, M.; Riese, H.; Bos, E.H.; Hankin, B. (2013). "Neuroticism and common mental disorders: Meaning and utility of a complex relationship". Clinical Psychology Review. 33 (5): 686–697. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.04.003. PMC 4382368. PMID 23702592.

- ^ a b c d Oatley, K., Keltner, D. & Jenkins, J. M. (2006b). "Emotions and mental health in childhood."Understanding emotions (2nd ed.) (pp. 321-351). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ Prevention Action. Diathesis-stress models Retrieved from http://www.preventionaction.org/reference/diathesis-stress-models Archived 2012-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lazarus, R. S. (January 1993). "From Psychological Stress to the Emotions: A History of Changing Outlooks". Annual Review of Psychology. 44 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245. PMID 8434890.

- ^ Meehl, Paul E. (1962). "Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia". American Psychologist. 17 (12): 827–838. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.2509. doi:10.1037/h0041029.

- ^ a b c d e Sigelman, C. K. & Rider, E. A. (2009). Developmental psychopathology. Life-span human development (6th ed.) (pp. 468-495). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- ^ a b c Oatley, K., Keltner, D., & Jenkins, J. M. (2006a). "Emotions and mental health in adulthood." Understanding Emotions (2nd ed.) (pp. 353-383). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ a b Gazelle, Heidi; Ladd, Gary W. (February 2003). "Anxious Solitude and Peer Exclusion: A Diathesis-Stress Model of Internalizing Trajectories in Childhood". Child Development. 74 (1): 257–278. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00534.

- ^ a b c Administration for Children and Families (2012). Preventing child maltreatment and promoting well-being: A network for action. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/guide2012/guide.pdf#page=9

- ^ a b Barlow, D. H. & Durand, V. M. (2009). Abnormal psychology: An integrative approach. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- ^ a b Masten, Ann S. (2001). "Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development". American Psychologist. 56 (3): 227–238. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. PMID 11315249.

- ^ a b c Belsky, Jay; Pluess, Michael (2009). "Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (6): 885–908. doi:10.1037/a0017376. PMID 19883141.

- ^ Jeronimus, B. F.; Kotov, R.; Riese, H.; Ormel, J. (15 August 2016). "Neuroticism's prospective association with mental disorders halves after adjustment for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, but the adjusted association hardly decays with time: a meta-analysis on 59 longitudinal/prospective studies with 443 313 participants". Psychological Medicine. 46 (14): 2883–2906. doi:10.1017/S0033291716001653. PMID 27523506.

- ^ Jeronimus, B. F.; Ormel, J.; Aleman, A.; Penninx, B. W. J. H.; Riese, H. (15 February 2013). "Negative and positive life events are associated with small but lasting change in neuroticism". Psychological Medicine. 43 (11): 2403–2415. doi:10.1017/S0033291713000159. PMID 23410535.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2008). "Suicide". Abnormal Psychology (4th ed.) (pp. 350-373). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ a b Monroe, Scott M.; Simons, Anne D. (1991). "Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders". Psychological Bulletin. 110 (3): 406–425. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. PMID 1758917.

- ^ Baldwin, AL (2006). "Mast cell activation by stress". Methods in Molecular Bology. 315: 349–60. doi:10.1385/1-59259-967-2:349. PMID 16110169.

- ^ https://www.immunology.org/public-information/bitesized-immunology/cells/mast-cells

- ^ Serpeloni, Fernanda; Radtke, Karl M.; Hecker, Tobias; Sill, Johanna; Vukojevic, Vanja; Assis, Simone G. de; Schauer, Maggie; Elbert, Thomas; Nätt, Daniel (16 April 2019). "Does Prenatal Stress Shape Postnatal Resilience? – An Epigenome-Wide Study on Violence and Mental Health in Humans". Frontiers in Genetics. 10. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Psychological vulnerability to stress in carriers of congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency". HORMONES. 16 (1). 12 May 2017. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1718.

- ^ Concolino, Paola (17 July 2019). "Issues with the Detection of Large Genomic Rearrangements in Molecular Diagnosis of 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 23 (5): 563–567. doi:10.1007/s40291-019-00415-z. PMID 31317337.

- ^ Ambeskovic, Mirela; Babenko, Olena; Ilnytskyy, Yaroslav; Kovalchuk, Igor; Kolb, Bryan; Metz, Gerlinde A. S. (23 April 2019). "Ancestral Stress Alters Lifetime Mental Health Trajectories and Cortical Neuromorphology via Epigenetic Regulation". Scientific Reports. 9 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42691-z.

- ^ Sinibaldi, Lorenzo; Ursini, Gianluca; Castori, Marco (March 2015). "Psychopathological manifestations of joint hypermobility and joint hypermobility syndrome/ Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type: The link between connective tissue and psychological distress revised". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 169 (1): 97–106. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31430. PMID 25821094.

- ^ Lewis, Candace Renee; Olive, Michael Foster (2014). "Early life stress interactions with the epigenome: potential mechanisms driving vulnerability towards psychiatric illness". Behavioural pharmacology. 25 (5 0 6): 341–351. doi:10.1097/FBP.0000000000000057. PMC 4119485. PMID 25003947.

- ^ Cummings, M. E., Davies, P. T., & Campbell, S. B. (2000). Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

External links

Media related to Diathesis–stress model at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Diathesis–stress model at Wikimedia Commons