Ager Vaticanus

In Ancient Rome, the Ager Vaticanus ([ˈa.ɡɛr waː.t̪iːˈkaː.n̪ʊs], "Vatican Field") was the alluvial plain on the right (west) bank of the Tiber. It was also called Ripa Veientana or Ripa Etrusca, indicating the Etruscan dominion during the archaic period.[1] It was located between the Janiculum, the Vatican Hill, and Monte Mario, down to the Aventine Hill and up to the confluence of the Cremera creek.[1]

Origin of the name

About the etymology of Vātī̆cānus there are several hypotheses: according to Barthold Georg Niebuhr, the toponym perhaps refers to an archaic Etruscan settlement called Vaticum;[2][3] Varro derives the name from a childbirth deity named Vaticanus or Vagitanus, the god of the vagiti ("wailings"), since va was supposed to be the first syllable pronounced by a child;[4][2] Aulus Gellius on his part derives the name from vāticinium, a prophecy elicited by the flight of the birds or from the study of the liver of the victims of sacrifices and inspired by the god who controlled the area:[4][2] the science of the Vaticini , the aruspicina or Etrusca Disciplina, had been introduced in Rome by the Etruscans.[5] This term was ultimately derived from vātēs (“soothsayer, prophet”) and canō (“to sing”).[6]

History

During the first centuries of Rome, the Ager Vaticanus was the boundary between Rome and the powerful Etruscan city of Veii.[1] After the Roman conquest of the rival city in 396 BC, the Centuriate Assembly kept the tradition of raising an ensign on the summit of the Janiculum hill, to signal a possible Etruscan raid. The hill was known as Antipolis ("anti-city" in Greek), in contrast with the Capitoline hill.

By the laws of the Duodecim Tabulae, insolvent debtors could be sold into slavery, but only on the right bank of the Tiber. After Cincinnatus paid a large punitive fine for his son, it was recorded that he retired "like an exiled man" to his property in the Ager Vaticanus, although the plain was already Roman territory.[1]

The toponym Ager Vaticanus is attested until the 1st century AD: afterwards, another toponym appeared, Vaticanus, denoting an area much more restricted: the Vatican hill, today's St. Peter's Square, and possibly today's Via della Conciliazione.[1]

Horti

The Ager Vaticanus lowland was exposed to the periodic floods of the Tiber, hosted vegetable gardens and vineyards, and was known for its unhealthy climate and bad wine[1][7] until the end of the first century BC, when the development of local roads along the Via Cornelia (towards the port of Caere), the via Triumphalis towards Veii and the via Aurelia nova[8] made possible for the families of the aristocracy the construction of luxurious private suburban residences (Horti).[1]

Excavations carried out in various periods in the area that stretches from Santo Spirito in Sassia[9] to the Palazzaccio have brought to light traces of 1st and 2nd century buildings, pertinent to the Horti Agrippinae ("Agrippina's gardens"), belonging to Agrippina the Elder, wife of Germanicus.[10] After her death, the Horti passed to her son Caligula, who had a hippodrome built there (the Circus Gaianus).[10] To mark its spina, Caligula erected in the circus an Egyptian obelisk (the only one always standing, among the numerous obelisks in Rome); it was later moved in 1586 by Pope Sixtus V (r. 1590-95) to St. Peter's Square.[9][11]

The circus and the Horti were inherited by Nero, who used both to lodge the Romans damaged by the great fire of 64, and to carry out the executions of the Christians accused of the fire itself.[11] Because of that, until the end of the Middle Ages the popular name of the area beyond the Tiber north of Trastevere remained Prata Neronis ("Nero's meadows").[12]

The neighboring Horti Domitiae ("Domitia's gardens"), owned either by Domitian's wife, Domitia Longina, or by Nero's aunt, Domitia Lepida the Younger,[13] also flowed into the imperial property; in this area Hadrian (r. 117-138) let later build his Mausoleum.[10] Further away from the river, Trajan had a Naumachia built, a facility intended to host naval battles.[14]

Roads

The Ager Vaticanus was serviced by two roads: the via Triumphalis and the via Cornelia.[15] Both roads are well known from the ancient authors, but their real paths are unknown.[15] There is consensus that the former, so called because of the triumphs of the Roman armies coming back from Veii, started in the Campus Martius, crossed the Tiber on the Pons Neronianus, heading north in direction Monte Mario and then flowing into the via Cassia;[15] About the Cornelia's path there are several hypotheses: until the 1940s was a common opinion that the road branched from the Triumphalis at a short distance from the bridge of Nero, running in east-west direction.[15] According to this hypothesis, the Christians condemned to death by Nero would have walked across this road while going to their martyrdom in the Circus of the emperor.[15] However, since during the excavations in Borgo during the 1940s for the building of Via della Conciliazione no sign of the road was found, now many scholars think that the via Cornelia started from Ponte Milvio and - running along the right bank of the Tiber - reached Hadrian's Mausoleum crossing the via Triumphalis in a place corresponding to the destroyed Piazza Scossacavalli in Borgo.[15] A third road, the via Aurelia nova, started from the Pons Aelius running southwest until today's Porta San Pancrazio.[15]

Burial areas

The Ager Vaticanus always remained outside the walls of Rome and the pomerium.[7] According to Roman tradition, therefore, necropolises and sepulchers also settled along the streets that crossed it,[16] and were normally left in place until the need arose to demolish them to make room for new buildings (like the Basilica of Saint Peter),[17] or to recover materials.[18]

This was the fate of the so-called Meta Romuli (the other funerary pyramid existing in Rome in addition to that of Gaius Cestius outside Porta San Paolo) [19] and the nearby large cylindrical monument with overlapping tower called Terebinthus Neronis; both burials were often considered in the Middle Ages as the place of Peter's martyrdom.[19] Traces of both monuments were found during the construction of the new buildings along Via della Conciliazione.[20]

Among the tombs, noteworthy is the one containing the sarcophagus of the young Crepereia Tryphaena; this contained, together with her funeral equipment, a doll with jointed arms.[21] This find, occurred in 1889, aroused much public emotion.[21]

The most recent discovery in this field (which occurred in 2003 but was published only in 2006) is that of the large necropolis known as Santa Rosa's,[16] along the via Triumphalis, which came to light during the excavation of the Vatican car park under the Janiculum hill. The latter site is not isolated, but constitutes a part of a vast burial ground which had been already discovered and explored in the 1950s, called "dell'Autoparco".[22]

St. Peter's tomb and the Constantinian basilica

In one of these very modest sepulchres, the body of Saint Peter was handed down after his crucifixion under Nero.[23] When Constantine legitimized the Christian cult with his Edict of Milan and began his Christian public building program with the Lateran, he didn't do so in the public spaces of Rome, but on areas lying to the margins of the urban area and belonging to the imperial state property.[24]

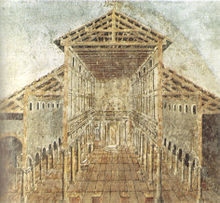

Thus began the construction, in the 4th century, of the first basilica dedicated to St. Peter, established according to Christian usage above what tradition claims is his tomb (the confessio), and founded on the north side of the Gaianum along the Via Cornelia.[23] Part of the surrounding necropolis was submerged under the construction of the church, but partly re-emerged during the research of the tomb of Peter conducted in the 1940s-1950s.[25]

Bridges

The Ager Vaticanus was connected to Rome through two bridges:

- Triumphal Bridge or Pons Neronianus in Sassiam, mentioned in the Mirabilia. The bridge was probably demolished during the construction of the Aurelian Walls,[26] but the remains of its pillars are visible still today during the lean flow periods of the Tiber.

- Pons Aelius or Pons Hadriani, then Ponte Sant'Angelo, built by Emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138) to connect his mausoleum with the city.[27]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Liverani (2016) p. 21

- ^ a b c Gigli (1990) p. 7

- ^ Lawrence Richardson (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 405.

- ^ a b Delli (1988) p. 947

- ^ Biondo, Flavio. "62". Memorie di varie antichità trovate in diversi luoghi della città di Roma (in Italian).

- ^ vaticinor in Charlton T. Lewis (1891) An Elementary Latin Dictionary, New York: Harper & Brothers

- ^ a b Gigli (1990) p. 8

- ^ Coarelli (1975) p. 311

- ^ a b Coarelli (1975) p. 318

- ^ a b c Coarelli (1975) p. 310

- ^ a b Liverani (2016) p. 23

- ^ Castagnoli, (1958), p. 239

- ^ Liverani (2016) p. 22

- ^ Coarelli (1975) p. 324

- ^ a b c d e f g Gigli (1990) p. 9

- ^ a b Liverani (2016) p. 24

- ^ Coarelli (1975), p. 320-321

- ^ Petacco (2016) p. 35-37

- ^ a b Petacco (2016), p. 34

- ^ AA.VV. (2003). Castel Sant'Angelo (in Italian). Electa. p. 14.

- ^ a b Anna Mura Sommella. "Crepereia Tryphaena" (in Italian). Rome: Corte Suprema di Cassazione. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Gigli (1990) p. 10

- ^ a b Coarelli (1974), p. 320

- ^ Krautheimer (1981), p. 34

- ^ Coarelli (1974), p. 319

- ^ Liverani (2016) p. 28

- ^ Coarelli (1974), p. 322

Sources

- Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Cecchelli, Carlo; Giovannoni, Gustavo; Zocca, Mario (1958). Topografia e urbanistica di Roma (in Italian). Bologna: Cappelli.

- Coarelli, Filippo (1974). Guida archeologica di Roma (in Italian). Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. ISBN 978-8804118961.

- Krautheimer, Richard (1981). Roma: Profilo di una città, 312-1308. Rome: Edizioni dell'Elefante. ISBN 8871760379.

- Delli, Sergio (1988). Le strade di Roma (in Italian). Rome: Newton & Compton.

- Gigli, Laura (1990). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Vol. Borgo (I). Rome: Fratelli Palombi Editori. ISSN 0393-2710.

- Petacco, Laura (2016). Claudio Parisi Presicce; Laura Petacco (eds.). La Meta Romuli e il Terebinthus Neronis (in Italian). Rome. ISBN 978-88-492-3320-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Liverani, Paolo (2016). Claudio Parisi Presicce; Laura Petacco (eds.). Un destino di marginalità: storia e topografia dell'area vaticana nell'antichità (in Italian). Rome. ISBN 978-88-492-3320-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)