Alastair McCorquodale

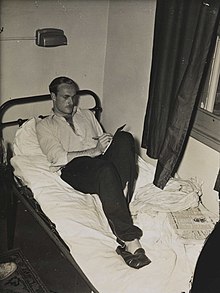

Alastair McCorquodale in the Olympic Village, London 1948 | |||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | |||||||||||||||

| Born | 5 December 1925 Hillhead, Glasgow | ||||||||||||||

| Died | 27 February 2009 (aged 83) Grantham, Lincolnshire | ||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 0 in (183 cm) | ||||||||||||||

| Weight | 172 lb (78 kg) | ||||||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||||||

| Coached by | Guy Butler (athletics - 1948) | ||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||

| Updated on 30 May 2016 | |||||||||||||||

Alastair McCorquodale (5 December 1925 – 27 February 2009[1]) was a British athlete and cricketer.[2]

McCorquodale was educated at Harrow where he opened the bowling for the 1st XI in the 1948 Eton v Harrow match at Lord's. He represented Britain in Athletics at the 1948 Olympic Games in London. He was denied a bronze medal in the 100m final by a photo finish, but won a silver medal in the 4 × 100 m relay. He never ran again.

He also represented the Free Foresters, Marylebone Cricket Club in 1948 and Middlesex in three matches in 1951, as a left-handed batsman and a right-arm fast bowler. He toured Canada with MCC in 1951–52. He was the seventh oldest living Middlesex first-class cricketer prior to his death.

Early life

McCorquodale was born in Hillhead, Glasgow City, on 5 December 1925.[3] He spent his childhood growing up in Essex, and was educated at Harrow School.[4][5] He was in both the football and cricket first XIs, and was in Elmfield House.[5][6][7]

Athletics career

As the Second World War was ending, he joined the Coldstream Guards straight out of school in 1944.[4][8] He was deployed to Germany as a Lieutenant, where he took up athletics to avoid having to do many drills.[4][9] He was successful at it, winning the army 100 metres title in 1946.[8] The following year he managed a sprint double, taking both the 100 metres and 200 metres titles.[10]

Success at the AAA Championships followed, as he took the 220 yards title in 1947.[11] He managed all of this while remaining rather unfocused on athletics, preferring rugby and cricket and having a relaxed attitude to training where it is said that he would stub out his cigarette to go on the track.[7]

He was coached by Guy Butler, when he joined London Athletic Club.[9] McCorquodale had a pair of running shoes made and Butler gave him a short plan, from which he went on to compete at the Olympics.[9]

In 1948 at the Summer Olympics, he competed individually in the 100 metres and the 200 metres, as well as part of the silver medal-winning quartet in the 4x100 metres relay.

1948 Olympics

The 1948 Olympics was regarded as odd as it did not have the electronic timing to 1/100th of a second that the previous two games in 1936 and 1932 had. Instead timing was done by hand to 1/10th of a second.[8]

100 metres

He competed in the 100 metres, negotiating a first and second round as well as a semi-final before making it to the final. He set times of 10.5, 10.5 and 10.7 seconds respectively, coming second in both the first and second round, then third in the semi-final. He then came fourth in the final, originally being awarded the same time as both second and third place, 10.4, but the medals were decided in a photo finish, with technology typically found on a racecourse being used to separate the athletes for the silver and bronze medals.[12]

200 metres

He also competed in the 200 metres, winning the tenth heat in 22.3 seconds in the first round. In the second round he ran half a second faster, running 21.8 to come second to the eventual Olympic champion Mel Patton, but he was finally knocked out by coming fifth in the second semi-final.[12]

4x100 metres relay

He ran in the relay along with John Gregory, the European 100 metres champion from two years prior, and Ken Jones and John Archer, both of whom were rugby internationals for Wales and England respectively.

The British team won their heat in 41.4 seconds, ahead of Hungary, who were awarded the same time.[12] In the final the British team ran 41.3 seconds, and came in second behind the Americans, but officials thought that the baton changeover between Barney Ewell and Lorenzo Wright of the USA was outside the box, and disqualified them, before reinstating them two days later after being presented with video evidence to the contrary, demoting the Britons back to second place and a silver medal.[8][9]

Cricket career

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 6 ft 0 in (183 cm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Left-handed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm fast | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1948 | Marylebone Cricket Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1950 | Free Foresters Cricket Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1950-51 | Middlesex Second XI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1951 | Middlesex County Cricket Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: [1], 30 May 2016 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

McCorquodale began his cricket career when a schoolboy at Harrow, playing for the 1st XI in 1943 and 1944, playing in the annual Eton vs Harrow match in both years. The first year, the match was rained off before he had come to bat.[13] The second year, he scored 27 and was the second highest scorer in the Harrow team as they lost by 5 wickets, bowling three of the Eton cricketers out before they successfully chased the total of 147 that had been set by Harrow.[14] He was then selected for Lord's Schools teams in both 1943 and 1944, before he left school.[15]

After his Olympic success, he picked cricket back up again in August 1948 playing for Marylebone Cricket Club both on tour in Ireland and in 1949 in Germany, taking six wickets in a match that was played against the British Army that were based in the region.[16][17]

After this he joined the Free Foresters Cricket Club, playing various matches for them including one against the Dutch national team.[18]

He joined the Marylebone Cricket Club again when they toured Canada in 1951, playing twelve games, including one against a Canadian XI.[19]

Personal life

He married Rosemary Turnor, a daughter of Major Herbert Broke Turnor and his wife Lady Enid Fane (a daughter of the 13th Earl of Westmorland). They had a daughter Sarah (who married Geoffrey van Cutsem, son of Bernard and brother of Hugh van Cutsem, in 1969) and a son Neil (who married Lady Sarah Spencer, sister of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1980).

Life after sport

After he retired from cricket he joined the family business, a printing firm named McCorquodale and Co., which had been responsible for printing the Olympic programmes in 1948 amongst other things.[8][20] He became chairman of the family firm in 1967, a role he took over from his cousin, and stayed in until he retired in 1986.[4][8] He also was on the boards of British Sugar and the Guardian Royal Exchange.[20]

He was a governor at Harrow school up until his death.

At one point in his fifties he chased two men off of his land, who were then both fined £60 for trespassing with a gun.[8]

After he retired he supported local charities and managed the family estate at Little Ponton Hall, where he had moved to in 1955 and where he lived until his death.[7][21] The estate's gardens are known to be very beautiful, spanning four acres, and in 2014 they were opened to the public, in aid of charity.[22]

He died aged 83, survived by his wife, son, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.[10]

Competition record

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representing | |||||

| 1948 | Olympics | London, England | 4th | 100 m | |

| 1948 | Olympics | London, England | 5th, SF 2 | 200 m | |

References

- ^ Matthews, Peter & Watman, Mel eds. Athletics International Vol 17, No6 – 3 March 2009

- ^ "Olympians Who Played First-Class Cricket". Olympedia. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Alastair McCorquodale". sports-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Former Olympic athlete dies aged 83". www.granthamjournal.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Alastair McCorquodale". Cricinfo. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "The Houses | Harrow School". www.harrowschool.org.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b c "McCorquodale, Alastair – Ran for England in London Olympics". Grantham Matters. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Alastair McCorquodale". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Track Stats - Alastair McCorquodale". www.nuts.org.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Alastair McCorquodale". Herald Scotland. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "British Athletics Championships 1945-1959". www.gbrathletics.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Official Report of the 1948 Olympics (PDF). LA84. 1948. pp. 242–245, 258.

- ^ "The Home of CricketArchive". www.cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "The Home of CricketArchive". www.cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "The Home of CricketArchive". www.cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "The Home of CricketArchive". www.cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "The Home of CricketArchive". www.cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "The Home of CricketArchive". www.cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "The Home of CricketArchive". www.cricketarchive.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Olympian McCorquodale dies aged 83". Cricinfo. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "A pleasure to play cricket with him". www.granthamjournal.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "Little Ponton Hall gardens to open for charity". www.granthamjournal.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

External links

- "Grantham Today"

- The Peerage

- Alastair McCorquodale, Track Stats, November 2007

- Alastair McCorquodale at Power of 10

- Alastair McCorquodale at ESPNcricinfo

- Alastair McCorquodale at CricketArchive (subscription required)

- 1925 births

- 2009 deaths

- People educated at Harrow School

- Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers

- Athletes (track and field) at the 1948 Summer Olympics

- Olympic athletes of Great Britain

- Olympic silver medallists for Great Britain

- Middlesex cricketers

- Scottish male sprinters

- Scottish cricketers

- Medalists at the 1948 Summer Olympics

- Scottish Olympic medallists

- Free Foresters cricketers

- Olympic silver medalists in athletics (track and field)

- People from Hillhead

- Sportspeople from Glasgow

- Sportspeople from Essex

- Cricketers from Glasgow

- British Army personnel of World War II

- Coldstream Guards officers