Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a pivotal policy statement first issued in August 1941 that early in World War II defined the Allied goals for the post-war world. It was drafted by Britain and the United States, and later agreed to by all the Allies. The Charter stated the ideal goals of the war: no territorial aggrandizement; no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people; restoration of self-government to those deprived of it; free access to raw materials; reduction of trade restrictions; global cooperation to secure better economic and social conditions for all; freedom from fear and want; freedom of the seas; and abandonment of the use of force, as well as disarmament of aggressor nations. In the "Declaration by United Nations" of 1 January 1942, the Allies of World War II pledged adherence to the charter's principles.

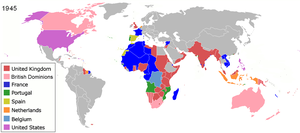

The Charter set goals rather than a blueprint for the postwar world. It inspired many of the international agreements that shaped the world. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the post-war independence of European colonies, and much more are derived from the Atlantic Charter.

Origin

The Atlantic Charter was drafted at the Atlantic Conference (codenamed Riviera) by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Newfoundland.[1] It was issued as a joint declaration on 14 August 1941. The United States did not officially enter the War until after the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The policy was issued as a statement; as such there was no formal, legal document entitled "The Atlantic Charter". It detailed the goals and aims of the Allied powers concerning the war and the post-war world.

Many of the ideas of the Charter came from an ideology of Anglo-American internationalism that sought British and American cooperation for the cause of international security.[2] Roosevelt's attempts to tie Britain to concrete war aims and Churchill's desperation to bind the U.S. to the war effort helped provide motivations for the meeting which produced the Atlantic Charter.[3] It was assumed at the time that Britain and America would have an equal role to play in any post war international organization that would be based on the principles of the Atlantic Charter.[4]

On 9 August 1941, HMS Prince of Wales sailed into Placentia Bay, with Winston Churchill on board, and met the USS Augusta where Roosevelt and his staff were waiting. On first meeting, Churchill and Roosevelt were silent for a moment until Churchill said "At long last, Mr. President", to which Roosevelt replied "Glad to have you aboard, Mr. Churchill". Churchill then delivered to the President a letter from King George VI and made an official statement which, despite two attempts, a sound-film crew present failed to record.

Content

The Atlantic Charter established a vision for a post-war settlement.

The eight principal points of the Charter were:

- no territorial gains were to be sought by the United States or the United Kingdom;

- territorial adjustments must be in accord with the wishes of the peoples concerned;

- all people had a right to self-determination;

- trade barriers were to be lowered;

- there was to be global economic cooperation and advancement of social welfare;

- the participants would work for a world free of want and fear;

- the participants would work for freedom of the seas;

- there was to be disarmament of aggressor nations, and a postwar common disarmament.

Point Four, with respect to international trade, consciously emphasized that both "victor [and] vanquished" would be given market access "on equal terms." This was a repudiation of the punitive trade relations that were established within Europe post-World War I, as exemplified by the Paris Economy Pact.

Origin of the name

When it was released to the public, the Charter was titled "Joint Declaration by the President and the Prime Minister" and was generally known as the "Joint Declaration". The name "Atlantic Charter" is believed to have been first coined by the Daily Herald newspaper,[5] but was used by Churchill in Parliament on 24 August 1941, and has since been generally adopted.

No signed version ever existed. The document was threshed out through several drafts and the final agreed text was telegraphed to London and Washington. President Roosevelt gave Congress the Charter's content on 21 August 1941.[6]

The British War Cabinet replied with its approval and a similar acceptance was telegraphed from Washington. During this process, an error crept into the London text, but this was subsequently corrected. The account in Churchill's The Second World War concludes "A number of verbal alterations were agreed, and the document was then in its final shape", and makes no mention of any signing or ceremony. Archives at the FDR Library show that at a press conference in December 1944, Roosevelt admitted that "nobody signed the Atlantic Charter." In Churchill's account of the Yalta Conference he quotes Roosevelt saying of the unwritten British constitution that "it was like the Atlantic Charter - the document did not exist, yet all the world knew about it. Among his papers he had found one copy signed by himself and me, but strange to say both signatures were in his own handwriting."[citation needed]

Acceptance by InterAllied Council and by United Nations

At the subsequent meeting of the Inter-Allied Council in St. James' Palace in London on 24 September 1941, the governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and representatives of General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, unanimously adopted adherence to the common principles of policy set forth in the Atlantic Charter.[7] On 1 January 1942, a larger group of nations, who adhered to the principles of the Atlantic Charter, issued a joint Declaration by United Nations stressing their solidarity in the defence against Hitlerism.[8]

Impact

The Axis Powers interpreted these diplomatic agreements as a potential alliance against them. In Tokyo the Atlantic Charter rallied support for the militarists in the Japanese government, who pushed for a more aggressive approach against the US and Britain.

The British dropped millions of flysheets over Germany to allay fears of a punitive peace that would destroy the German state. The text cited the Charter as the authoritative statement of the joint commitment of Great Britain and the U.S. "not to admit any economical discrimination of those defeated" and promised that "Germany and the other states can again achieve enduring peace and prosperity."[9]

The agreement proved to be one of the first steps towards the formation of the United Nations.[10]

Impact on imperial powers

The problems came not from Germany and Japan, but from those of the allies that had empires and which resisted self-determination--especially Britain, the Soviet Union and the Netherlands. Initially it appears that Roosevelt and Churchill had agree that the third point of Charter was not going to apply to Africa and Asia.[11] However Roosevelt's speechwriter Robert Sherwood noted that "it was not long before the people of India, Burma, Malaya, and Indonesia were beginning to ask if the Atlantic Charter extended also to the Pacific and to Asia in general." With a war that could only be won with these allies, Roosevelt's solution was to put some pressure on Britain but to postpone until after the war the issue of self-determination of the colonies.[12] In a speech a year after the Charter was published he avoided the issue of whether it applied to the rest of the world even though the Office of War Information draft of the speech had explicitly said it did.[13]

British Empire

Public opinion in Britain and the Commonwealth was delighted with the principles of the meetings but disappointed that the U.S. was not entering the war. Churchill admitted that he had hoped the U.S. would finally decide to commit itself.

The acknowledgment that all peoples had a right to self-determination gave hope to independence leaders in British colonies (e.g., India).[14]

In a September 1941 speech, Churchill stated that the Charter was only meant to apply to states under German occupation, and certainly not to the peoples who formed part of the British Colonial Empire.[15]

Churchill rejected its universal applicability when it came to the self-determination of subject nations such as British India. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in 1942 wrote to President Roosevelt: "I venture to think that the Allied declaration that the Allies are fighting to make the world safe for the freedom of the individual and for democracy sounds hollow so long as India and for that matter Africa are exploited by Great Britain..."[16] Roosevelt repeatedly brought the need for Indian independence to Churchill's attention, but was repeatedly rebuffed.[16] However Gandhi and his party refused to help either the British or the American war effort against Germany and Japan in any way, leaving Roosevelt no choice but to back Churchill.[17] India eventually ended up contributing significantly to the war effort, sending over 2.5 million men (the largest volunteer force in the world at the time) to fight for the Allies, mostly in West Asia and North Africa. [18]

Poland

Churchill was unhappy with the inclusion of references to peoples' right to "self-determination" and stated that he considered the Charter an "interim and partial statement of war aims designed to reassure all countries of our righteous purpose and not the complete structure which we should build after the victory."[19] An office of the Polish Government in Exile wrote to warn Władysław Sikorski that if the Charter was implemented with regards to national self-determination, it would make the desired Polish annexation of Danzig, East Prussia and parts of German Silesia impossible, which led the Poles to approach Britain asking for a flexible interpretation of the Charter.[19]

Baltics

During the war Churchill argued for an interpretation of the charter in order to allow Russia to continue to control the Baltic states, an interpretation rejected by the U.S. until March 1944.[20] Lord Beaverbrook warned that the Atlantic Charter "would be a menace to our [Britain's] own safety as well as to that of Russia." The U.S. refused to recognize the Soviet takeover of the Baltics, but did not press the issue against Stalin when he was fighting the Germans.[21] Roosevelt planned to raise the Baltic issue after the war, but he died in April 1945.[22]

See also

Notes

- ^ M.S. Venkataramani, "The United States, the Colonial Issue, and The Atlantic Charter Hoax", International Studies, 13:1 1974, pp.16.

- ^ Nicholas Cull, "Selling p66eace: the origins, promotion and fate of the Anglo-American new order during the Second World War", Diplomacy and Statecraft, vol 3#1 1996, pp.4,6.

- ^ Nicholas Cull, "Selling peace: the origins, promotion and fate of the Anglo-American new order during the Second World War", Diplomacy and Statecraft, vol 3#1 1996, pp.15.

- ^ Nicholas Cull, "Selling peace: the origins, promotion and fate of the Anglo-American new order during the Second World War", Diplomacy and Statecraft, vol 3#1 1996, pp.21.

- ^ M.S. Venkataramani, "The United States, the Colonial Issue, and The Atlantic Charter Hoax", International Studies, 13:1 1974, pp.3. Reference is in footnote on this page.

- ^ President Roosevelt's message to the U. S. Congress on 21 August 1941

- ^ Inter-Allied Council Statement on the Principles of the Atlantic Charter on 24 September 1941

- ^ Joint Declaration by the United Nations of 1 January 1942

- ^ Ernst Sauer, "Grundlehre des Völkerrechts", 2nd edition, Balduin Pick, Cologne 1948, p. 407

- ^ Atlantic Charter

- ^ M.S. Venkataramani, "The United States, the Colonial Issue, and The Atlantic Charter Hoax", International Studies, 13:1 1974, pp.20.

- ^ Elizabeth Borgwardt, A new deal for the world: America's vision for human rights (2005) p. 29

- ^ M.S. Venkataramani, "The United States, the Colonial Issue, and The Atlantic Charter Hoax", International Studies, 13:1 1974, pp.22.

- ^ Bayly, C., and Harper, T., 2004. Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941-1945. Belknap Press

- ^ Neta C. Crawford, Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, and Humanitarian Intervention (Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 297 (Google books)

- ^ a b Kanishkan Sathasivam, Uneasy Neighbors: India, Pakistan, and US Foreign Policy, p. 59 Google books

- ^ William Roger Louis, Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonization (2006), p. 400

- ^ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission Report on India 2007–2008" (PDF). Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ^ a b Anita Prażmowska, "Britain and Poland, 1939-1943: the betrayed ally, Part 750", p. 93 (Google books)

- ^ Roger S. Whitcomb, The Cold War in Retrospect: The Formative Years (Praeger, 1998), p. 18;

- ^ William Roger Louis, More adventures with Britannia (1998) p. 224

- ^ Townsend Hoopes and Douglas Brinkley, FDR and the Creation of the U.N. (2000) p 52

Bibliography

- Beschloss, Michael R. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 (2002)

- Douglas G Brinkley and David Facey-Crowther, eds. The Atlantic Charter (1994)

- Charmley, John. "Churchill and the American Alliance," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6th Ser., Vol. 11 (2001), pp. 353-371 in in JSTOR

- Cull, Nicholas. "Selling peace: the origins, promotion and fate of the Anglo-American new order during the Second World War," Diplomacy and Statecraft, vol 3#1 1996, pp. 1-28

- Kimball, Warren. Forged in war: Churchill, Roosevelt and the Second World War (1997)

- Smith, Jean Edward. FDR (2008) pp. 481-505

- Venkataramani, M.S. "The United States, the Colonial Issue, and The Atlantic Charter Hoax", International Studies, 13:1 1974, pp.1-28.

External links

- BBC News

- The Atlantic Conference from the Avalon Project

- Letter from The Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley to the U.S. Secretary of State TEHRAN, April 14, 1945. Describing meeting with Churchill, where Churchill vehemently states that the U.K. is in no way bound to the principles of the Atlantic Charter.

- The Atlantic Charter