George Rhoads

George Rhoads | |

|---|---|

George Rhoads with his ball machine, "Peaceaball Kingdom" | |

| Born | George Pitney Rhoads January 27, 1926 |

| Died | July 9, 2021 (aged 95) Chinon, France |

| Education | University of Chicago, Chicago Art Institute |

| Known for | Audiokinetic Sculptures, Ball Machines, Origami, Painting, Wind Sculpture |

| Notable work | 42nd Street Ballroom, Port Authority Bus Terminal, New York, New York Newton's Daydream, Clark Planetarium, Salt Lake City, Utah Tower of Sisyphus, Chesapeake Energy Corporation, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Having a Ball, Ontario Science Center, Toronto, Ontario University Hospitals, Cleveland, Ohio |

| Movement | Kinetic Art |

| Website | georgerhoads |

George Rhoads (January 27, 1926 – July 9, 2021) was a contemporary American painter, sculptor, and origami master. He was best known for his whimsical audiokinetic sculptures in airports, science museums, shopping malls, children’s hospitals, and other public places throughout the world.

Early life

George Rhoads was born in Evanston, Illinois, the oldest of four children. His father, Paul S. Rhoads, was a physician and professor of internal medicine at Northwestern University. His mother, Hester Chapin Rhoads, was trained as an interior decorator.[1]

Rhoads attended the University of Chicago with the goal of studying physics and mathematics. After earning enough credits to complete his associate degree, Rhoads began taking design and drawing classes at Chicago’s Art Institute. Two years later he left Chicago and moved to New York City to become a painter. His work focused on portraits and impressionistic cityscapes, but he was not critically or financially successful.[1]

In 1952, Rhoads moved to Paris to continue painting. It was there that he met American origami expert Gershon Legman who introduced him to the art of origami and the work of Akira Yoshizawa. This meeting sparked Rhoads’ interest and he began practicing origami and inventing new folds. His most notable contribution to the field became known as the Blintzed Bird Base, now a standard origami fold used for creating an animal with four legs, two ears, and a tail from a single sheet of paper.[2]

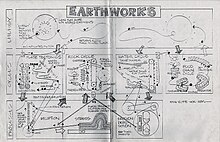

Audiokinetic Ball Machine Sculptures

In the 1960s, Rhoads began experimenting with kinetic sound-producing metal sculptures. As he described these early machines: “You have a whole range of things happening in succession. Little balls rolling down a track are the motive power that hits a hammer that hits a xylophone bar or blows a whistle.” After seeing an exhibit of Rhoads' ball machines in Greenwich Village, sculptor Hans Van de Bovenkamp hired him to invent devices to use in his metal fountains. Eventually, Rhoads began creating fountains of his own.[1]

Rhoads continued to develop his audio-kinetic sculptures and his work gained national prominence after being featured on The David Frost Show and the Today show.[3] In the early 1970s, shopping mall magnate David Bermant commissioned Rhoads to build audiokinetic sculptures for his shopping centers in Rochester, New York, and Hamden, Connecticut, and for years afterward continued to promote and sell Rhoads’ work.[4]

Rhoads’ sculptures became known for their precise clockwork-like mechanisms governed by weight and timing while still maintaining the appearance of spontaneity and randomness. He promoted the concept that the machine itself was a work of art, and his pieces were designed to demystify machinery and stimulate viewer reaction.[5] Modernist sculptor and Professor Emeritus at Princeton University, James Seawright, said of Rhoads' sculptures: "they embody almost every basic element of machinery, combined in a bewildering variety of ways. There's a level of mechanical genius behind inventing complex mechanisms."[6]

In response to the growing number of commissions, Rhoads partnered with Robert McGuire to create his sculptures at RockStream Studios in Ithaca, NY. The studio and Rhoads’ whimsical sculptures were later featured in an episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.[7]

In 1981, Rhoads was commissioned to build a sculpture entitled 42nd Street Ballroom for the New York/New Jersey Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York City, which ushered in a period of production for larger, monumental ball machine sculptures.[8] In these large machines, chain-driven lifters carry balls to the top of the sculpture. Then, using only gravity, the balls travel down several different tracks that loop, twist, and spiral. The balls trigger motion, hit objects, strike bells, gongs, chimes, drums and even xylophone bars, allowing each machine to create its own music. Once the ball reaches the bottom of the sculpture, it is lifted to the top and the process continues.[9]

Over the last fifty years, Rhoads’ sculptures have been installed in public spaces and private collections around the world.[8] The pieces range in size from small wall-mounted sculptures to machines that fill entire rooms and span multiple stories.[10] Some of his work belongs to permanent museum collections at institutions like the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago.[5] Nearly all of his sculptures are still in operation today, and have been noted for their popularity with the public.[8]

In 2007, Creative Machines (located in Tucson, Arizona) took over the creation of Rhoads’ sculptures, and continues the tradition of Rhoads’ artwork today. The company continues to use the techniques developed by George Rhoads in their ball machine sculptures by incorporating similar fabrication methods, design elements, and strategies for making reliable, long lasting sculptures.[6]

Death

Rhoads died at his son's home in Chinon, France, on July 9, 2021, at the age of 95.[11]

Selected public works

- The "Gizmo" in Champlain Centre Mall, Plattsburgh, New York[12]

- 42nd Street Ballroom, Port Authority Bus Terminal, New York, New York

- Exercise in Fugality, Logan Airport, Terminal A, Boston, Massachusetts

- Science on a Roll, The Tech Museum of Innovation, San Jose, California

- Archimedean Excogitation, Museum of Science, Boston, Massachusetts

- Uridice, Discovery Science Center, Costa Mesa, California

- Maquina del Vacilon, Papalote Museo del Nino, Mexico City, Mexico

- Celestial Balldergarten, Philadelphia International Airport, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Global Enerjoy, Future Energy Pavilion, Seville Expo ’92, Seville, Spain

- Incrediball Circus II, Akron Children's Hospital, Akron, Ohio

- Angel Music, Los Angeles International Airport, Los Angeles, California

- Life Renews Itself, Ōsaka Namba Station, Osaka, Japan

- Color Coaster, Stepping Stones Museum for Children, Norwalk, Connecticut

- Newton’s Daydream, Clark Planetarium, Salt Lake City, Utah

- Pythagorean Fantasy, College of Engineering at the University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado

- Based on Balls, Chase Field, Phoenix, Arizona

- Loopy Links, Adventure of the Seas, Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines

- Funkinetic, Science Centre Singapore, Singapore

- Eureka, Discovery Communications, Bethesda, Maryland

- Ball Circus, ABT Electronics, Glenview, Illinois

- Kinetikon, National Taiwan Science Education Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

- Cavortech, Avampato Discovery Museum, Charleston, West Virginia

- Tower of Sisyphus, Chesapeake Energy Corporation, Oklahoma City Oklahoma

- Life is a Ball, Scientific Games, Las Vegas, Nevada

- Magic Menagerie, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan[10]

- Electric Ball Circus, Edmonton science centre (formerly at West Edmonton Mall)

Museums/collections

Museums

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City

- The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois

- The Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio

- The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut[10]

- Franklin Institute of Science, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. "Newton's Convergence"

Collections

- Leonard Bernstein

- Malcolm Forbes

- Lawrence Tisch

- David Elliot

- Herbert Adler

- Yevgeny Yevtushenko

- David Bermant

- William Marsteller

- American Scientific Company

- Westinghouse Electric Company[10]

Gallery

-

Chockablock Clock Ball Machine, located in Strawberry Square, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

-

Archimedean Excogitation can be found at the Boston Museum of Science and is said to hold the attention of viewers for much longer than many of the other exhibits housed there.

Further reading

- Brown, Suzanne. “Machine for the Manufacture of Automatic Spontaneity Arrives at Museum.” Press release for exhibit at the Arnot Art Museum, Elmira, NY, 1975.

- Case, Richard G. “Audiokinetic Exhibit Stars at Everson.” Syracuse Herald-American 8 Feb. 1976: 30.

- Crawford, Franklin. Colossuses of Rhoads.” Ithaca Journal. 10 Nov. 1989: B12.

- Donnelly, Kathleen. “Whole New Ball Game.” San Jose Mercury News 5 Jan. 1995: C1.

- Gibson, Sheila. “Follow the Bouncing Ball.” Robb Report. Dec. 2000: 102-03.

- Hall, Tony. “The Moving, Noisy Sculpture of George Rhoads.” Ithaca Times 12 July 1984: 16-18.

- James, Rebecca. “Quantum’s Last Leap.” Syracuse Herald-American 2 Oct. 1994: 17-19.

- Kelly, Lili. “Ball Machines Mix Gravity and Levity.” Ithaca Child. Winter 1994.

- Kostelanetz, Richard. “Clumper Upper to Wok Dumper to chute to Helix to Block.” Smithsonian Oct. 1988: 135- 45.

- “Sculpture Funhouse.” New York Times Magazine 31 May 1987: 28-31.

- Melrod, George.

- Meras, Phyllis. “Island Artist Creates Machines that Spin but Do Not Toil.” Vineyard Gazette 27 Mar. 1970:

- Protter, Eric, ed. Painters on Painting. Mineola, New York: Dover Pub., Inc., 1997: 270-271.

- Rhoads, George. Interview in museum catalog with Louise Weinberg, Asst. Curator of the Queens Museum exhibit: “George Rhoads: Audiokinetic Sculptures,” July 30-Sept. 20, 1987.

- Schoch, Deborah. “Ping, Blip, Bong.” Ithaca Journal 20 Sept. 1983.

- Schwartz, Wylie. “All Eyes on Rhoads.” Ithaca Times 19 Mar. 2008: 7-9.

- Sherman, Tamar Asedo. “What Is That Strange Contraption?” Ithaca Journal 20 Sept. 1983.

- Spring, Justin. Review of exhibit at the Ruth Siegel Gallery, New York. Art Forum April 1992:

- Winter, Metta. “Art in Motion.” Shopping Centers Today May 1988.

- “Krazy Kinetic Kontraptions.” Christian Science Monitor 5 Feb. 1988: 21-22.

- “Mesmerizing Machines.” SKY Magazine May 1988: 28-34.

- Zimmer, William. “Art for the Public with an element of Fun.” New York Times 22 July 1984: 22.

References

- ^ a b c Johnson 2011, pp. 2–26.

- ^ Harbin 1997, pp. 236–244.

- ^ Watkins 2006, p. 215.

- ^ "Stop, Signs!". The Village Voice. December 8, 1987. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "George Rhoads". The David Bermant Foundation: Color, Light, Motion. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Creative Machines Ball Machine Sculptures" (PDF). Creative Machines. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ "When Things Get Broken". Season 29, Episode 13. Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. March 25, 1999.

- ^ a b c Weigang, Jim (October 1988). "Clumper Upper to Wok Dumper to Chute to Helix to Block". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Caney & 2006 347.

- ^ a b c d "George Rhoads: Ball Machine Sculpture Catalog" (PDF). Creative Machines. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ "George Rhoads". Ithaca.com. July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ Finckel, Joe (November 2, 2019). "A Love Note to the Plattsburgh Ball Machine". Press-Republican. Plattsburgh, NY.

Bibliography

- Johnson, Emily Rhoads (2011). Wizard at Work: The Life and Art of George Rhoads. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 9781608449682.

- Harbin, Robert (1997). Secrets of Origami: The Japanese Art of Paper Folding. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications Inc. ISBN 9780486297071.

- Watkins, Susan M. (2006). Conversations with Seth: Book Two. Needham: Moment Point Press. ISBN 9781930491090.

- Caney, Steven (2006). george rhoads artist. Philadelphia, PA: Running Press Kids. pp. 347.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)