Graphene lens

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Graphene applications as optical lenses. The unique honeycomb 2-D structure of graphene contributes to its unique optical properties. The honeycomb structure allows electrons to exist as massless quasiparticles known as Dirac fermions.[1] Graphene’s optical conductivity properties are thus unobstructed by any material parameters represented by equation 1, where e is the electron charge, h is Planck’s constant and "e^2"/"h" represents the universal conductance.[2]

- Equation 1

This simple behavior is the result of an undoped graphene material at zero temperature (figure 1a).[3] In contrast to traditional semiconductors or metals (figure 1b); graphene’s band gap are near nonexistent as the conducting and valence bands make contact (figure 1a). However, the band gap is tunable via doping and electrical gating, resulting in changes in graphene’s optical properties.[4] As a result of its tunable conductivity, graphene is employed in various optical applications.

Graphene lenses as ultra-broad photodetectors

Electrical gating and doping allows for adjustment of graphene’s optical absorptivity.[5][6] The application of electric fields transverse to staggered graphene bilayers generates a shift in Fermi energy and an artificial, non-zero band gap (equation 2[7] figure 1).

- Equation 2

δD=Dt - Db where Dt = top electrical displacement field

Db = bottom electrical displacement field

Varying δD above or below zero(δD=0 denotes non-gated, neutral bilayers) allows electrons to pass through the bilayer without altering the gating-induced band gap.[8] As shown in Figure 2, varying the average displacement field, ▁D, alters the bilayer’s absorption spectra. The optical tunability resulting from gating and electrostatic doping (also known as charge plasma doping[9]) lends to the application of graphene as ultra-broadband photodetectors in lenses.[10]

Chang-Hua et al. implemented graphene in an infrared photodetector by sandwiching an insulating barrier of Ta2O5 between two graphene sheets.[11] The graphene layers became electrically isolated and exhibited an average Fermi difference of 0.12eV when a current was passed through the bottom layer (figure 3). When the photodetector is exposed to light, excited hot electrons transitioned from the top graphene layer to the bottom, a process promoted by the structural asymmetry of the insulating Ta2O5 barrier.[12][13] A consequence of the hot electron transition, the top layer accumulates positive charges and induces a photogating [14][15] effect on the lower graphene layer, which is measured as a change in current correlating with photon detection.[16] Utilizing graphene both as a channel for charge transport and light absorption, the graphene ultra-broadband photodetectors ably detects the visible to mid-infrared spectrum. Nanometers thin and functional at room temperature, graphene ultra-broadband photodetectors show promise in lens application.

Graphene lenses as Fresnel zone plates

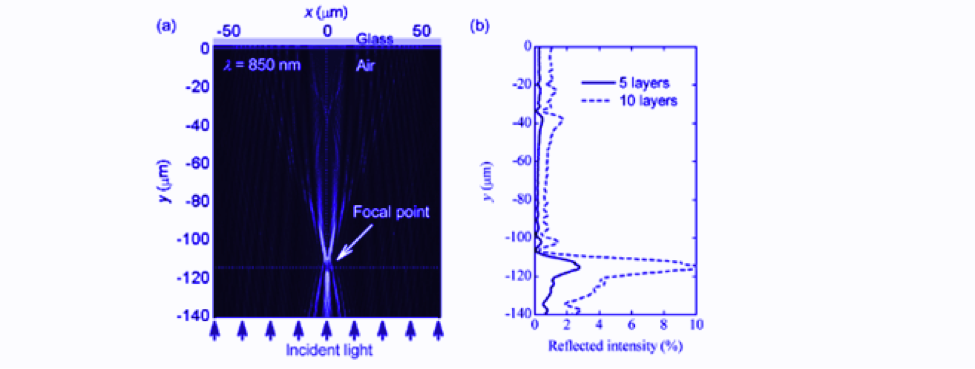

Figure 4 the graphene Fresnel Zone Plate reflects the light off to a single point.[17] [18]

Fresnel zone plates are devices that focus light on a fixed point in space. These devices concentrate light reflected off a lens onto a singular point8 (figure 4). Composed of a series of discs centered about an origin, Fresnel zone plates are manufactured using laser pulses, which embed voids into reflective lens.

Despite its weak reflectance (R = 0.25π2 α 2 at T = 1.3 × 10-4 K), graphene has utility as a lens for Fresnel zone plates.[19] It has been shown that graphene lenses effectively concentrate light of ʎ = 850 nm onto a single point 120 um away from the Fresnel zone plate8[20] (figure 5). Further investigation illustrates that the reflected intensity increases linearly with the number of graphene layers within the lens[21] (figure 6).

Graphene lenses as transparent conductors

Optoelectronic components such as light-emitting diode (LED) displays, solar cells, and touch screens require highly transparent materials with low sheet resistance, Rs. For a thin film, the sheet resistance is given by equation 3:

- Equation 3

with t = film thickness

A material with tunable thickness, t, and conductivity, σ, possesses useful optoelectronic applications if Rs is reasonably small. Graphene is such a material; the amount of graphene layers that comprise the film can tune t and the inherent tunability of graphene’s optical properties via doping or grating can tune sigma. Figure 7[22][23][24] shows graphene’s potential relative to other known transparent conductors.

The need for alternate transparent conductors is well documented.[25][26][27] Current semiconductor based transparent conductors such as doped indium oxides, zinc oxides, or tin oxides suffer from practical downfalls including rigorous processing requirements, prohibitive cost, sensitivity toward acidic or basic media, and a brittle consistency. However, graphene does not suffer from these downfalls.

References

- ^ Geim, A. K.; Novoselov, K. S. (March 2007). "The rise of graphene". Nature Materials. 6 (3): 183–191. Bibcode:2007NatMa...6..183G. doi:10.1038/nmat1849. PMID 17330084.

- ^ Grigorenko, A. N.; Polini, M.; Novoselov, K. S. (5 November 2012). "Graphene plasmonics". Nature Photonics. 6 (11): 749–758. arXiv:1301.4241. Bibcode:2012NaPho...6..749G. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2012.262.

- ^ Li, Z. Q.; Henriksen, E. A.; Jiang, Z.; Hao, Z.; Martin, M. C.; Kim, P.; Stormer, H. L.; Basov, D. N. (8 June 2008). "Dirac charge dynamics in graphene by infrared spectroscopy". Nature Physics. 4 (7): 532–535. doi:10.1038/nphys989.

- ^ Zhang, Yuanbo; Tang, Tsung-Ta; Girit, Caglar; Hao, Zhao; Martin, Michael C.; Zettl, Alex; Crommie, Michael F.; Shen, Y. Ron; Wang, Feng (11 June 2009). "Direct observation of a widely tunable bandgap in bilayer graphene". Nature. 459 (7248): 820–823. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..820Z. doi:10.1038/nature08105. PMID 19516337.

- ^ Koppens, F. H. L.; Mueller, T.; Avouris, Ph.; Ferrari, A. C.; Vitiello, M. S.; Polini, M. (6 October 2014). "Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems". Nature Nanotechnology. 9 (10): 780–793. Bibcode:2014NatNa...9..780K. doi:10.1038/nnano.2014.215.

- ^ Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, C.; Girit, C.; Zettl, A.; Crommie, M.; Shen, Y. R. (11 April 2008). "Gate-Variable Optical Transitions in Graphene". Science. 320 (5873): 206–209. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..206W. doi:10.1126/science.1152793.

- ^ Zhang, Yuanbo; Tang, Tsung-Ta; Girit, Caglar; Hao, Zhao; Martin, Michael C.; Zettl, Alex; Crommie, Michael F.; Shen, Y. Ron; Wang, Feng (11 June 2009). "Direct observation of a widely tunable bandgap in bilayer graphene". Nature. 459 (7248): 820–823. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..820Z. doi:10.1038/nature08105. PMID 19516337.

- ^ Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, C.; Girit, C.; Zettl, A.; Crommie, M.; Shen, Y. R. (11 April 2008). "Gate-Variable Optical Transitions in Graphene". Science. 320 (5873): 206–209. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..206W. doi:10.1126/science.1152793.

- ^ Hueting, R. J. E.; Rajasekharan, B.; Salm, C.; Schmitz, J. (2008). "The charge plasma p-n diode". IEEE Electron Device Letters. 29 (12): 1367–1369. Bibcode:2008IEDL...29.1367H. doi:10.1109/LED.2008.2006864.

- ^ Liu, Chang-Hua; Chang, You-Chia; Norris, Theodore B.; Zhong, Zhaohui (16 March 2014). "Graphene photodetectors with ultra-broadband and high responsivity at room temperature". Nature Nanotechnology. 9 (4): 273–278. Bibcode:2014NatNa...9..273L. doi:10.1038/nnano.2014.31.

- ^ Liu, Chang-Hua; Chang, You-Chia; Norris, Theodore B.; Zhong, Zhaohui (16 March 2014). "Graphene photodetectors with ultra-broadband and high responsivity at room temperature". Nature Nanotechnology. 9 (4): 273–278. Bibcode:2014NatNa...9..273L. doi:10.1038/nnano.2014.31.

- ^ Liu, Chang-Hua; Chang, You-Chia; Norris, Theodore B.; Zhong, Zhaohui (16 March 2014). "Graphene photodetectors with ultra-broadband and high responsivity at room temperature". Nature Nanotechnology. 9 (4): 273–278. Bibcode:2014NatNa...9..273L. doi:10.1038/nnano.2014.31.

- ^ Lee, C.-C.; Suzuki, S.; Xie, W.; Schibli, T. R. (17 February 2012). "Broadband graphene electro-optic modulators with sub-wavelength thickness". Optics Express. 20 (5): 5264. doi:10.1364/OE.20.005264.

- ^ Liu, Chang-Hua; Chang, You-Chia; Norris, Theodore B.; Zhong, Zhaohui (16 March 2014). "Graphene photodetectors with ultra-broadband and high responsivity at room temperature". Nature Nanotechnology. 9 (4): 273–278. Bibcode:2014NatNa...9..273L. doi:10.1038/nnano.2014.31.

- ^ Li, Hongbo B. T.; Schropp, Ruud E. I.; Rubinelli, Francisco A. (2010). "Photogating effect as a defect probe in hydrogenated nanocrystalline silicon solar cells". Journal of Applied Physics. 108 (1): 014509. Bibcode:2010JAP...108a4509L. doi:10.1063/1.3437393.

- ^ Zhang, Yuanbo; Tang, Tsung-Ta; Girit, Caglar; Hao, Zhao; Martin, Michael C.; Zettl, Alex; Crommie, Michael F.; Shen, Y. Ron; Wang, Feng (11 June 2009). "Direct observation of a widely tunable bandgap in bilayer graphene". Nature. 459 (7248): 820–823. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..820Z. doi:10.1038/nature08105. PMID 19516337.

- ^ Kong, Xiang-Tian; Khan, Ammar A.; Kidambi, Piran R.; Deng, Sunan; Yetisen, Ali K.; Dlubak, Bruno; Hiralal, Pritesh; Montelongo, Yunuen; Bowen, James; Xavier, Stéphane; Jiang, Kyle; Amaratunga, Gehan A. J.; Hofmann, Stephan; Wilkinson, Timothy D.; Dai, Qing; Butt, Haider (18 February 2015). "Graphene-Based Ultrathin Flat Lenses". ACS Photonics. 2 (2): 200–207. doi:10.1021/ph500197j.

- ^ Watanabe, Wataru; Kuroda, Daisuke; Itoh, Kazuyoshi; Nishii, Junji (23 September 2002). "Fabrication of Fresnel zone plate embedded in silica glass by femtosecond laser pulses". Optics Express. 10 (19): 978. Bibcode:2002OExpr..10..978W. doi:10.1364/OE.10.000978.

- ^ Kong, Xiang-Tian; Khan, Ammar A.; Kidambi, Piran R.; Deng, Sunan; Yetisen, Ali K.; Dlubak, Bruno; Hiralal, Pritesh; Montelongo, Yunuen; Bowen, James; Xavier, Stéphane; Jiang, Kyle; Amaratunga, Gehan A. J.; Hofmann, Stephan; Wilkinson, Timothy D.; Dai, Qing; Butt, Haider (18 February 2015). "Graphene-Based Ultrathin Flat Lenses". ACS Photonics. 2 (2): 200–207. doi:10.1021/ph500197j.

- ^ Kong, Xiang-Tian; Khan, Ammar A.; Kidambi, Piran R.; Deng, Sunan; Yetisen, Ali K.; Dlubak, Bruno; Hiralal, Pritesh; Montelongo, Yunuen; Bowen, James; Xavier, Stéphane; Jiang, Kyle; Amaratunga, Gehan A. J.; Hofmann, Stephan; Wilkinson, Timothy D.; Dai, Qing; Butt, Haider (18 February 2015). "Graphene-Based Ultrathin Flat Lenses". ACS Photonics. 2 (2): 200–207. doi:10.1021/ph500197j.

- ^ Kong, Xiang-Tian; Khan, Ammar A.; Kidambi, Piran R.; Deng, Sunan; Yetisen, Ali K.; Dlubak, Bruno; Hiralal, Pritesh; Montelongo, Yunuen; Bowen, James; Xavier, Stéphane; Jiang, Kyle; Amaratunga, Gehan A. J.; Hofmann, Stephan; Wilkinson, Timothy D.; Dai, Qing; Butt, Haider (18 February 2015). "Graphene-Based Ultrathin Flat Lenses". ACS Photonics. 2 (2): 200–207. doi:10.1021/ph500197j.

- ^ Bae, Sukang; Kim, Hyeongkeun; Lee, Youngbin; Xu, Xiangfan; Park, Jae-Sung; Zheng, Yi; Balakrishnan, Jayakumar; Lei, Tian; Ri Kim, Hye; Song, Young Il; Kim, Young-Jin; Kim, Kwang S.; Özyilmaz, Barbaros; Ahn, Jong-Hyun; Hong, Byung Hee; Iijima, Sumio (20 June 2010). "Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes". Nature Nanotechnology. 5 (8): 574–578. Bibcode:2010NatNa...5..574B. doi:10.1038/nnano.2010.132. PMID 20562870.

- ^ Geng, Hong-Zhang; Kim, Ki Kang; So, Kang Pyo; Lee, Young Sil; Chang, Youngkyu; Lee, Young Hee (June 2007). "Effect of Acid Treatment on Carbon Nanotube-Based Flexible Transparent Conducting Films". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (25): 7758–7759. doi:10.1021/ja0722224. PMID 17536805.

- ^ Lee, Jung-Yong; Connor, Stephen T.; Cui, Yi; Peumans, Peter (February 2008). "Solution-Processed Metal Nanowire Mesh Transparent Electrodes". Nano Letters. 8 (2): 689–692. Bibcode:2008NanoL...8..689L. doi:10.1021/nl073296g.

- ^ Minami, Tadatsugu (1 April 2005). "Transparent conducting oxide semiconductors for transparent electrodes". Semiconductor Science and Technology. 20 (4): S35–S44. Bibcode:2005SeScT..20S..35M. doi:10.1088/0268-1242/20/4/004.

- ^ Holland, L.; Siddall, G. (October 1953). "the properties of some reactively sputtered metal oxide films". Vacuum. 3 (4): 375–391. doi:10.1016/0042-207X(53)90411-4.

- ^ Hamberg, I.; Granqvist, C. G. (1986). "Evaporated Sn-doped In2O3 films: Basic optical properties and applications to energy-efficient windows". Journal of Applied Physics. 60 (11): R123. Bibcode:1986JAP....60R.123H. doi:10.1063/1.337534.