Iron triangle (US politics)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

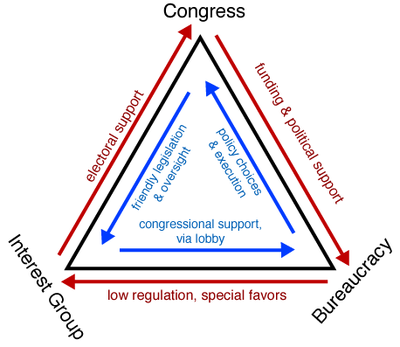

In United States politics, the iron triangle comprises the policy-making relationship among the congressional committees, the bureaucracy, and interest groups.[1]

Central assumption

Central to the concept of an iron triangle is the assumption that bureaucratic agencies, as political entities, seek to create and consolidate their own power base. In this view an agency's power is determined by its constituency, not by its consumers. (For these purposes, "constituents" are politically active members sharing a common interest or goal; consumers are the expected recipients of goods or services provided by a governmental bureaucracy and are often identified in an agency's written goals or mission statement.)

Apparent bureaucratic dysfunction may be attributable to the alliances formed between the agency and its constituency. The official goals of an agency may appear to be thwarted or ignored altogether at the expense of the citizenry it is designed to serve.

Cultivation of a constituency

The need of a bureaucracy for a constituency sometimes leads to an agency's cultivation of a particular clientele. An agency may seek out those groups (within its policy jurisdiction) that will make the best allies and give it the most clout within the political arena.

Often, especially in a low-level bureaucracy, the consumers (the supposed beneficiaries of an agency's services) do not qualify as power brokers and thus make poor constituents. Large segments of the public have diffused interests, seldom vote, may be rarely or poorly organized and difficult to mobilize, and are often lacking in resources or financial muscle. Less-educated and poorer citizens, for example, typically make the worst constituents from an agency's perspective.

Private or special interest groups, on the other hand, possess considerable power as they tend to be well-organized, have plenty of resources, are easily mobilized, and are extremely active in political affairs, through voting, campaign contributions, and lobbying, as well as proposing legislation themselves.

Thus it may be in an agency's interest to switch its focus from its officially-designated consumers to a carefully selected clientele of constituents that will aid the agency in its quest for greater political influence.

Dynamics

In the United States, power is exercised in the Congress, and particularly in congressional committees and subcommittees. By aligning itself with selected constituencies, an agency may be able to affect policy outcomes directly in these committees and subcommittees. This is where an iron triangle may manifest itself. The picture above displays the concept.

At one corner of the triangle are interest groups (constituencies). These are the powerful interest's groups that influence Congressional votes in their favor and can sufficiently influence the re-election of a member of Congress in return for supporting their programs. At another corner sit members of Congress who also seek to align themselves with a constituency for political and electoral support. These congressional members support legislation that advances the interest group's agenda. Occupying the third corner of the triangle are bureaucrats, who are often pressured by the same powerful interest groups their agency is designated to regulate. The result is a three-way, stable alliance that is sometimes called a sub-government because of its durability, impregnability, and power to determine policy.

An iron triangle can result in the passing of very narrow, pork-barrel policies that benefit a small segment of the population. The interests of the agency's constituency (the interest groups) are met, while the needs of consumers (which may be the general public) are passed over. That public administration may result in benefiting a small segment of the public in this way may be viewed as problematic for the popular concept of democracy if the general welfare of all citizens is sacrificed for very specific interests. This is especially so if the legislation passed neglects or reverses the original purpose for which the agency was established. Some maintain that such arrangements are consonant with (and are natural outgrowths of) the democratic process, since they frequently involve a majority block of voters implementing their will through their representatives in government.

See also

References

- ^ Hayden, F. (June 2002). "Policymaking Network of the Iron-Triangle Subgovernment for Licensing Hazardous Waste Facilities". Journal of Economic Issues. 36 (2): 479. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Gordon Adams. The Iron Triangle: The Politics of Defense Contracting, Council on Economic Priorities, New York, 1981. ISBN 0-87871-012-4

- Graham T. Allison, Philip Zelikow; Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, Pearson Longman; ISBN 0-321-01349-2 (2nd edition, 1999)

- Peter Gemma, Op/Ed: "Iron Triangle" Rules Washington, USA Today, December 1988, Retrieved May 23, 2016 [1]

- Hugh Heclo; Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment

- Jack H. Knott, Gary J. Miller; Reforming Bureaucracy; Prentice-Hall; ISBN 0-13-770090-3 (1st edition, 1987)

- Francis E. Rourke; Bureaucracy, Politics, and Public Policy Harpercollins; ISBN 0-673-39475-1 (3rd edition, 1984)

- Hedrick Smith; The Power Game: How Washington Really Works

- Ralph Pulitzer, Charles H. Grasty