For He's a Jolly Good Fellow

| "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" | |

|---|---|

| Song | |

| Genre | popular song |

"For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" is a popular song that is sung to congratulate a person on a significant event, such as a promotion, a birthday, a wedding (or playing a major part in a wedding), a retirement, a wedding anniversary, the birth of a child, or the winning of a championship sporting event. The melody originates from the French song "Malbrough s'en va-t-en guerre" ("Marlborough Has Left for the War").

History

[edit]The tune is of French origin and dates at least from the 18th century.[1] Allegedly it was composed the night after the Battle of Malplaquet in 1709.[2] It became a French folk tune and was popularised by Marie Antoinette after she heard one of her maids singing it.[3] The melody became so popular in France that it was used to represent the French defeat in Beethoven's composition Wellington's Victory, Op. 91, written in 1813.[4]

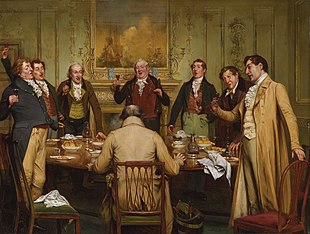

The melody also became widely popular in the United Kingdom.[5] By the mid-19th century[6] it was being sung with the words "For he's a jolly good fellow", often at all-male social gatherings,[7] and "For she's a jolly good fellow", often at all-female social gatherings. By 1862, it was already familiar in the United States.[8]

The British and the American versions of the lyrics differ. "And so say all of us" is typically British,[9] while "which nobody can deny" is regarded as the American version,[4] but the latter has been used by non-American writers, including Charles Dickens in Household Words,[10] Hugh Stowell Brown in Lectures to the Men of Liverpool[11] and James Joyce in Finnegans Wake.[12] (In the short story "The Dead" from Dubliners, Joyce has a version that goes, "For they are jolly gay fellows..." with a refrain between verses of "Unless he tells a lie".) The 1935 American film Ruggles of Red Gap, set in rural Washington State, ends with repeated choruses of the song, with the two variations sung alternately.[citation needed]

Text

[edit]As with many songs that use gender-specific pronouns, the song can be altered to match with the gender of the intended recipient.[13] If the song is being sung to two or more people, it is altered to use plurals.

British version

[edit]

For he's a jolly good fellow, for he's a jolly good fellow

For he's a jolly good fellow, and so say all of us!

American version

[edit]For he's a jolly good fellow, for he's a jolly good fellow

For he's a jolly good fellow, which nobody can deny!

Melody

[edit]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd. ed. (revised). Ed. Michael Kennedy: "18th‐cent. Fr. nursery song. ... It is usually stated that 'Malbrouck' refers to the 1st Duke of Marlborough, but the name is found in medieval literature."

- ^ Catalogue of rare books of and relating to music. London: Ellis. 1728. p. 32.

- ^ West, Nancy Shohet (9 June 2011). "Mining nuggets of music history". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ a b Cryer, Max (2010). Love Me Tender: The Stories Behind the World's Favourite Songs. Exile Publishing. pp. 26 ff. ISBN 978-1-4587-7956-4.

- ^ The Times (London, England), 28 March 1826, p. 2: "The Power of Music: A visiting foreigner, trying to recall the address of his lodgings in Marlborough Street, hums the tune to a London cabman: he immediately recognises it as 'Malbrook'".

- ^ The song may have featured in an "extravaganza" given at the Princess Theatre in London at Easter 1846, during which fairies hold a moonlight meeting: "...the meeting closes with a song of thanks to Robin Goodfellow (Miss Marshall), who had occupied the chair, ...and who is assured that 'he's a jolly good fellow'." "Princess's." The Times (London, England) 14 April 1846: 5. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 1 October 2012.[full citation needed]

- ^ The Times reprinted an article from Punch describing a drunken speech given at a (fictional) public meeting. The speech ends: "Zshenl'men, here's all your vehgood healts! I beggapard'n – here's my honangal'n fren's shjolly goo' health! 'For he's a jolly good fellow', &c (Chorus by the whole of the company, amid which the right hon. orator tumbled down.)" "The After Dinner Speech at the Improvement Club". The Times, (London, England) 23 March 1854: 10. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 1 October 2012.[full citation needed]

- ^ Review of a piano recital: "As a finale he performed for the first time, a burlesque on the French air, 'Marlbrook', better known to the American student of harmony as 'He's a jolly good fellow'." The New York Times, 4 October 1862

- ^ An 1859 version quoted in The Times, however, has some "red-faced" English officers at an Indian entertainment dancing before their host: "...declaring that he was 'a right good fellow; he's a jolly good fellow, which nobody dare deny hip, hip, hip, hoorah!' &c." The Times (London, England), 24 March 1859, p. 9

- ^ Dickens, Charles (1857). Household Words. Vol. 15. p. 142.

- ^ Brown, Hugh Stowell (1860). Lectures to the Men of Liverpool. p. 73.

- ^ Joyce, James (2006). Finnegans Wake. JHU Press. p. 569. ISBN 9780801883828.

- ^ Originally the song was associated with after-dinner drinking by all-male groups and not used for females. In 1856, British officers in the Crimea mistakenly sang it after a toast had been made, in Russian, to the Empress of Russia: "...peals of laughter followed when they all learned the subject of the toast, which was afterwards drunk again with due honour and respect." Blackwood's Magazine, vol. 80, October 1856