Kartinah

| Kartinah | |

|---|---|

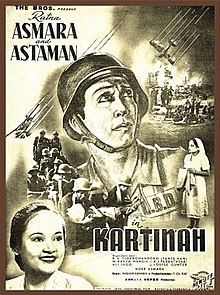

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Andjar Asmara |

| Written by | Andjar Asmara |

| Produced by | The Teng Chun |

| Starring |

|

Production company | New Java Industrial Film |

Release date |

|

| Country | Dutch East Indies |

| Language | Indonesian |

Kartinah is a now-lost 1940 romance film from the Dutch East Indies that was written and directed by Andjar Asmara. The film, Andjar's directorial debut, follows a nurse and her superior as they fall in love in the Air Raid Preparation team. Produced by The Teng Chun's New Java Industrial Film, Kartinah was heavily subsidised by the country's government and through product placement. Although it was a critical failure, the new actors signed with the studio for Kartinah gave New Java Industrial Film increased production capabilities.

Plot

Suria (Astaman), a commander at the Air Raid Preparation team (Lucht Beschermings Dienst, or LBD), has fallen in love with the nurse Kartinah (Ratna Asmara), who serves with the LBD. However, he is married to Titi (Tante Han), a woman who has lost her sanity. Although Suria's uncle (R. Inoe Perbatasari) suggests that Suria take Kartinah as a second wife, Kartinah refuses, as she considers herself a modern woman and not bound by traditional practices.[1]

In an airstrike, Titi is heavily wounded; the presence of danger jolts her mind enough that she regains her sanity. She explains that she and Suria have long been sleeping in different beds, and expresses hope that Kartinah will be willing to take him as her husband. Kartinah and her childhood friend, Dr. Rasyid (Rasjid Manggis), try unsuccessfully to save Titi's life. Afterwards Kartinah agrees to marry Suria.[1]

Production

Andjar Asmara, who directed Kartinah, had previous experience as the editor-in-chief of the film magazine Doenia Film (1929–1930) and dramatist for the theatrical group Dardanella.[2] He was invited to direct by The Teng Chun, an ethnic Chinese film producer and head of Java Industrial Film;[3] Andjar also wrote the film's script.[4] Several cast members were drawn from the Dardanella troupe, including Astaman, Ali Joego, and M. Rasjid Manggis, while R. Inoe Perbatasari had formerly worked with Andjar's troupe Bollero.[5] Kartinah was Andjar's directorial debut and the film debut of several of its actors.[2]

Andjar and his wife, Ratna, were each given 1,000 gulden for their work, Andjar as director and Ratna as an actress. The couple also received a 10 per cent share of the net profits. This fee, twice that earned by stars for other studios, was made possible by a subsidy from the LBD.[a][6] Funds from the LBD and Department of Internal Affairs were also used in production, allowing for the filming of expensive effects and scenes, including one with a large fire[5] and the first airstrike in the country's cinema.[7] Despite this, the Indonesian sociologist A. Budi Susanto notes that the film put its love story first, leaving the role of the LBD in the background.[8] Further funds were drawn from product placement: a Singer sewing machine and two local magazines.[5]

Kartinah was originally meant to be titled Kartini. However, this proved controversial owing to the title's reminiscence of the female emancipation figure, Kartini. Filming began in early 1940 and received the attentions of numerous local groups, who visited the set.[9] The film was in black-and-white.[4]

Release and reception

Kartinah was released in late 1940, during a time of increased intellectualism in local films. Although audiences had high expectations, the academia were later critical of the film; they considered it as nothing more than entertainment, not having any educational value.[9] However, the influx of new talent led Java Industrial Film to expand into different areas, creating subsidiaries for action and mystery films.[5]

The film is likely lost. The American visual anthropologist Karl G. Heider writes that all Indonesian films from before 1950 are lost.[10] However, JB Kristanto's Katalog Film Indonesia (Indonesian Film Catalogue) records several as having survived at Sinematek Indonesia's archives, and film historian Misbach Yusa Biran writes that several Japanese propaganda films have survived at the Netherlands Government Information Service.[11]

Notes

- ^ The LBD had been established after the outbreak of World War II in Europe to train civilians to deal with expected air raids from the Empire of Japan, which had already made aggressive moves towards mainland China (Sardiman 2008, p. 8).

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b Biran 2009, pp. 266–267.

- ^ a b Said 1982, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 212.

- ^ a b Filmindonesia.or.id, Kartinah.

- ^ a b c d Biran 2009, p. 214.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 213.

- ^ Prawirawinta & 195?, p. 74.

- ^ Susanto 2003, p. 241.

- ^ a b Biran 2009, p. 266.

- ^ Heider 1991, p. 14.

- ^ Biran 2009, p. 351.

Bibliography

- Biran, Misbach Yusa (2009). Sejarah Film 1900–1950: Bikin Film di Jawa [History of Film 1900–1950: Making Films in Java] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Komunitas Bamboo working with the Jakarta Art Council. ISBN 978-979-3731-58-2.

- Heider, Karl G (1991). Indonesian Cinema: National Culture on Screen. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1367-3.

- "Kartinah". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Prawirawinta, Susi S (n.d.). Indonesia in Brief. Jakarta: Endang. OCLC 606488.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Said, Salim (1982). Profil Dunia Film Indonesia [Profile of Indonesian Cinema] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Grafiti Pers. OCLC 9507803.

- Sardiman (2008). Guru Bangsa: Sebuah Biografi Jenderal Sudirman [Teacher of the People: A Biography of General Sudirman] (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Ombak. ISBN 978-979-3472-92-8.

- Susanto, A. Budi (2003). Identitas Dan Postkolonialitas Di Indonesia [Identity and Postcolonialism in Indonesia]. Yogyakarta: Kanisius. ISBN 978-979-21-0851-4.