Nikolaos Gripiotis

Nikolaos Gripiotis | |

|---|---|

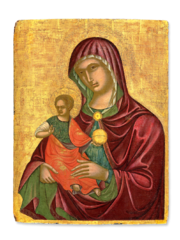

Example of Mass Produced Works during his Period in Crete | |

| Born | 1465 |

| Died | 1525 |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Known for | Mass Producing Greek Icons in the 1500s |

| Movement | Cretan School |

| Spouse | Maria |

| Children | Ioannis, Kassandra, Francheskina |

| Patron(s) | Giorgio Basejo and Petro Varsama |

| Occupation | Painter |

| Years active | 1480–1525 |

| Era | Greek Renaissance |

| Style | Maniera Greca |

| Relatives | Brother-in-law Arsenius Apostolius |

Nikolaos Gripiotis(Greek: Νικόλαος Γριπιώτης, 1465–1525) aka Nicolò Gripioti was a Greek painter and teacher. He is one of the most important painters of the early 1500s because he mass-produced Greek icons with Michael Fokas and Giorgio Miçocostantin (Georgios Mitsoconstantinos). He was a prominent member of the Cretan School. Regrettably non of his signed works exist but records indicate he completed thousands of paintings with his coworkers. Notable painters at the time were Andreas Pavias and Nikolaos Tzafouris. Local painters followed specific design prototypes some of the works are very similar. There is a huge assortment of unattributed works belonging to the Cretan School. Nikolaos's son Ioannis Gripiotis also became a prominent painter he is listed in countless archives of the period. Regrettably non of his works survived. Some of the archives mention specific types of works and titles. He was very important. His wife's brother was Arsenius Apostolius.[1][2][3][4][5]

History

Nikolaos was born on the Island of Crete he was the son of Marino. Marino was a jeweler. Nikolaos married Maria and had three children Kassandra, Francheskina, and Ioannis. Maria's brother Arsenius Apostolius was a priest and eventually became the Archbishop of Monemvasia. Nikolao's daughter Francheskina married Mattheos de Mediolano.[5] Nikolaos was a professional painter. Countless records exist describing the painter's activity from 1480 to 1525. In 1493, he accepted Marino Nicola di Giorgio as his painting student. In 1499, records indicated that Nikolaos, Michael Fokas and George Mitsoconstantinos accepted a contract to paint 700 icons for two vendors. Three hundred paintings were requested to follow the Italian style and 400 the Greek style. The works were created in three different sizes. Records indicate a month prior Nikolaos's coworker Michael Fokas hired famous woodcarver Giorgio Sclavo to cut one thousand wood panels in three different sizes specifically for paintings.[2] On the fourth of July 1499, Michael Fokas was contracted to paint 100 icons in a month and a half. He also promised 100 more icons painted by Nikolaos.[6] By 1503, Nikolaos was still active as a teacher of painting. He signed another contract to train Ioannis Synadenos for four years. Two years later in the summer of 1505 on June 5, 1505, he received 6 golden Venetian ducats and 5 superpyras for a magnificent icon of Saint Christopher. He completed the work for the chapel of Petros Bono. The chapel was located in the Catholic monastery of Saint Peter. Regrettably non of the famous painters works were signed and it is difficult to attribute work to the artist. There are thousands of unsigned unattributed works that follow the style of the period. His signature would have been Χείρ Γριπιώτης or in latin Nicolò Gripioti Pinxit.[1][7][8][9]

Gallery

-

Italian Style Cretan Prototype

-

Greek Style Cretan Prototype

-

Italian Style Cretan Prototype

-

Mass Produced Cretan Prototype

References

- ^ a b Hatzidakis 1987, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Voulgaropoulou 2020, pp. 217.

- ^ Baltoyanni, Chrysanthi (1994). Icons Mother of God. Athens, GR: Adam Editions. p. 40. ISBN 9789605000950.

- ^ Vasilaki, Maria (2009). The Painter Angelos and Icon-painting in Venetian Crete. Burlington, VT: Ashgate/Variorum. p. 38. ISBN 9780754659457.

- ^ a b Kondi 1989, pp. 201.

- ^ Hatzidakis & Drakopoulou 1997, pp. 452.

- ^ Eugenia Drakopoulou (July 21, 2022). "Νικόλαος Γριπιώτης (Greek)". Institute for Neohellenic Research. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Carol M.; Woods, Kim W.; Lymberopoulou, Angeliki (2007). Viewing Renaissance Art. New York: Yale University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0300123432.

- ^ Reynolds, Daniel; Brubaker, Leslie; Darley, Rebecca (2022). Global Byzantium: Papers from the Fiftieth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 189. ISBN 9781000624489.

Bibliography

- Hatzidakis, Manolis (1987). Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450-1830). Τόμος 1: Αβέρκιος - Ιωσήφ [Greek Painters after the Fall of Constantinople (1450-1830). Volume 1: Averkios - Iosif]. Athens: Center for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation. hdl:10442/14844. ISBN 960-7916-01-8.

- Voulgaropoulou, Margarita (2020). "From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic". Religions. 10 (6): 390. doi:10.3390/rel10060390.

- Hatzidakis, Manolis; Drakopoulou, Evgenia (1997). Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450-1830). Τόμος 2: Καβαλλάρος - Ψαθόπουλος [Greek Painters after the Fall of Constantinople (1450-1830). Volume 2: Kavallaros - Psathopoulos]. Athens: Center for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation. hdl:10442/14088. ISBN 960-7916-00-X.

- Kondi, B. (1989). Τὰ Εθνικὰ Οἰκογενειακὰ Όνόματα στὴν Κρήτη κατὰ τὴ βενετοκρατία (13ος-17ος αἰ.) [The Family Names of People Residing in Crete from the 12th-17th Century] (PDF). Athens GR: The Public Research Foundation of Byzantine Research.