Outer Space Treaty

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

| Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies | |

|---|---|

| Signed | 27 January 1967 |

| Location | London, Moscow and Washington |

| Effective | 10 October 1967 |

| Condition | 5 ratifications, including the depositary Governments |

| Parties | 100[1] |

| Depositary | Governments of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United States of America |

| Languages | Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish |

| Full text | |

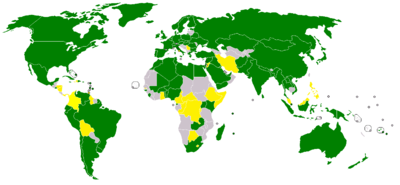

The Outer Space Treaty, formally the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, is a treaty that forms the basis of international space law. The treaty was opened for signature in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union on January 27, 1967, and entered into force on October 10, 1967. As of October 2011, 100 countries are states parties to the treaty, while another 26 have signed the treaty but have not completed ratification.[1]

Key points

The Outer Space Treaty represents the basic legal framework of international space law. Among its principles, it bars States Parties to the Treaty from placing nuclear weapons or any other weapons of mass destruction in orbit of Earth, installing them on the Moon or any other celestial body, or to otherwise station them in outer space. It exclusively limits the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes and expressly prohibits their use for testing weapons of any kind, conducting military maneuvers, or establishing military bases, installations, and fortifications (Art.IV). However, the Treaty does not prohibit the placement of conventional weapons in orbit. The treaty also states that the exploration of outer space shall be done to benefit all countries and shall be free for exploration and use by all the States.

The treaty explicitly forbids any government from claiming a celestial resource such as the Moon or a planet, claiming that they are the Common heritage of mankind.[2] Art. II of the Treaty states that "outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means". However, the State that launches a space object retains jurisdiction and control over that object.[3] The State is also liable for damages caused by their space object and must avoid contaminating space and celestial bodies.[4]

Responsibility for activities in space

Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty deals with international responsibility, stating that "the activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty" and that States Parties shall bear international responsibility for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities.

As a result of discussions arising from Project West Ford in 1963, a consultation clause was included in Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty: "A State Party to the Treaty which has reason to believe that an activity or experiment planned by another State Party in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, would cause potentially harmful interference with activities in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, may request consultation concerning the activity or experiment."[5][6]

Follow-ups

- The Moon Treaty of 1979 was meant to be the follow-up to the Outer Space Treaty, but failed to be ratified by any space-faring nation.[citation needed]

- Both the Space Preservation Treaty and the Space Preservation Act of 2001[7][clarification needed] are expansions on the ban of weapons in space, being a ban on all weapons, instead of only nuclear and WMDs, but both so far have had minimal success.[8][9]

See also

| International ownership treaties |

|---|

- Fractional Orbital Bombardment System

- High-altitude nuclear explosion (HANE)

- Militarization of space

- Lunar Flag Assembly

References

- J. Hickman and E. Dolman. "Resurrecting the Space Age: A State-Centered Commentary on the Outer Space Regime." Comparative Strategy. vol. 21, no. 1, (2002).

Citations

- ^ a b "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, includingthe Moon and Other Celestial Bodies". 1/1/08. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|authorlink= - ^ Jennifer Frakes, The Common Heritage of Mankind Principle and the Deep Seabed, Outer Space, and Antarctica: Will Developed and Developing Nations Reach a Compromise? Wiscoscin International Law Journal. 2003; 21:409

- ^ "Article VIII - Outer Space Treaty of 1967 - Wikisource".

- ^ "Article VII - Outer Space Treaty of 1967 - Wikisource".

- ^ Terrill Jr., Delbert R. (May 1999), Project West Ford, "The Air Force Role in Developing International Outer Space Law" (PDF), Air Force History and Museums:63-67

- ^ "Article IX - Outer Space Treaty of 1967 - Wikisource".

- ^ "Space Preservation Act of 2001". Fas.org. 2001-10-02. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ^ "Space Preservation Act". SourceWatch. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ^ "H.R. 2977 [107th]: Space Preservation Act of 2001". GovTrack.us. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

External links

- International Institute of Space Law

- Full text of the "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies" in Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, or Spanish

- The Case for Withdrawing From The 1967 Outer Space Treaty

- Still Relevant (and Important) After All These Years: The case for supporting the Outer Space Treaty

- Squadron Leader KK Nair's "Space:The Frontiers of Modern Defence" Knowledge World Publishers, New Delhi, Chap-5 (Examining Space Law...), Pg 84–104, available at [1]

- "Land Sale's over the moon" Sydney Morning Herald, 13 October 2003

- Arms control treaties

- Cold War treaties

- Treaties of the Soviet Union

- Soviet Union–United States relations

- Treaties of the United States

- Nuclear weapons policy

- Space weapons

- Space law

- 1967 in spaceflight

- 1967 in military history

- Treaties establishing nuclear-weapon-free zones

- Treaties concluded in 1967

- Treaties entered into force in 1967