Pain management in children

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (August 2017) |

| Pain management in children |

|---|

Pain management in children is defined as the assessment then treatment of pain in infants and children. According to Stanford Children's Hospital, pain is a sensation of discomfort, distress or agony.[1] In physiological terms, pain can induce nerve stimulation and conduction of nerve impulses to the brain. Stimulations can be mild, localized, chronic, acute or agonizing. Similar to adults, a child's pain is often tied to emotional and psychological components.[2] Untreated pain can greatly increase the chances of further complications and even death.[3] With this being said, it is important to identify the cause of pain quickly in order to avoid detrimental consequences.[4] There is even a possibility that children can have significant pain related to Epidermolysis Bullosa, Osteogenesis Imperfecta, cancer, metabolic/neurologic diseases, palliative care, and sickle cell disease.[5] A clinician described the use of evidence-based approaches to managing pain in children: "Pain management practices should be based on scientific facts or agreed best practices, not on personal beliefs or opinion. The burden of proof lies with the healthcare professional, NOT the patient."[6] Unfortunately, many of the problems that cause children pain are undertreated.[4]

Indications

The indications for needed treatment in children are not always clear due to misconceptions.

| Incorrect | Valid | References |

|---|---|---|

| Infants cannot sense pain like adults | Nerve pathways exist at birth, though immature newborns experience physiological changes and surge in hormones that indicate stress |

[7][4] |

| Infants cannot feel pain because of unmyelinitated nerve fibers |

Complete myelination is not necessary for the transmission of pain impulses to the brain |

[7] |

| Younger children cannot indicate where pain originates | Younger children have the cognitive ability to use a body chart and explain where their pain is coming from | [7] |

| A child is able to sleep then they are not in pain |

Sleep occurs because of exhaustion | [8] |

| "Pain builds character" | Unacceptable | [4] |

Treatments can vary among health care providers and are subject to the providers' personalities, culture, beliefs and acceptance of pain in children. Characteristics of pain typically help determine assessment, diagnosis and treatment. Pain can be acute, recurrent, chronic or a combination of these. It can also occur simultaneously in other parts of the body. Pain in children is characterized as having "plasticity and complexity" and in need of timely and continuous assessment. In order to receive the best results, a child should be asked to describe the pain before the questioning of location, intensity, quality, and tolerance. Sometimes, providers' viewpoints and assumptions involving the meaning of a behavior need evaluation. There is "a relatively pervasive and systematic tendency for proxy judgments to underestimate the pain experience of others".[4] The suggested treatments for pain do not always resolve the problem. In some cases, treatments and medications for pain actually cause pain. Minor invasive procedures often don't include a treatment plan for anticipated pain. For example, during circumcision infants do not consistently receive the appropriate pain control. Not only are newborn circumcisions painful, they are also associated with irritability and feeding disturbances for days after the procedure.[4]

Acute pain

Usually, acute pain is generated from an obvious cause and is expected to last for only a few days or weeks. It is usually managed with medication and non-pharmacological treatment to provide comfort.[9][1] Acute pain is an indication for needed assessment, treatment and prevention. While a child is experiencing pain, physiological changes occur that can further jeopardize healing and recovery. Unrelieved pain can cause alkalosis and hypoxemia that result from rapid, shallow breathing. This shallow breathing then leads to the accumulation of fluid in the lungs, taking away to the ability to cough. Dangerously enough, this can prevent the secretions from being expelled. Pain can cause an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, creating great stress on the heart. Additionally, pain increases the release of anti-inflammatory steroids that reduce the ability to fight infection. These same steroids that are released increase the metabolic rate and impact healing. Another harmful outcome of acute pain is an increase in sympathetic effects such as the inability to urinate. Such aches can even slow down the gastrointestinal system.

Inadequate pain management in children can lead to psycho-social consequences. Disinterest in food, apathy, sleep problems, anxiety, avoidance of discussions about health, fear, hopelessness and powerlessness are just some of the many. Other consequences can be extended hospital stays, high readmission rates and a longer recovery.[10] On the other hand, the American Association of Pediatrics describes pain with immunizations as "The pain associated with the majority of immunizations is minor.".[11]

Examples of harmful consequences due to unrelieved pain:[12]

- infants with a higher than average heel sticks can have poor cognitive and motor function

- distress caused by needle-sticks make medical treatments later on more difficult

- children who have experienced invasive procedures often times develop post-traumatic stress (PST)

- boys circumcised without anesthesia were found to have greater distress than uncircumcised boys. [13]

- severe pain as a child is associated with higher reports of pain in adults [14]

Acute pain can be expected in response to many if not most invasive procedures. Anticipation of pain and distress can guide a pre-treatment, pain-prevention plan based on past reports of pain associated with the medical procedure. Individuals with technical expertise and experience are more likely to minimize the pain as much as possible. Preparation before a procedure with information that is understood by children and parents decrease distress. Parents can contribute to the improvement of this issue by learning effective methods/ways to comfort their child.[4] Types of procedures determine the use of deep sedation or anesthesia. In some cases, the best method to prevent and relieve pain is by building self-esteem. Suggested cognitive behavioral strategies are: imagery, relaxation, a massage, heat compression, calm adults, a quiet environment, and confident explanations by providers. Since distress can be addressed and controlled, some children benefit from the opportunity for self-regulation. Pain reduction during invasive procedures is closely linked to controlling distress. Treating distress even for minor or uncomplicated procedures, likes venipuncture can be implemented.[4]

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain is associated with nerve injuries or abnormal sensitivities to touch or contact. Other causes are, postsurgical, post-amputation.[5]

Cancer pain

Cancer pain can differ from other types of pain. The level of pain experienced by a child that has this disease is related to the stage or extent of the cancer. Children with cancer may have no pain at all, it varies. One child may have a different threshold for pain than another may.

Sources of cancer pain are:

- a growing tumor pressing on a body organ or nerves

- inadequate blood circulation because of blocked blood vessels

- blockage of an organ or a 'tube' of the organ

- the spread of the cancer to other places

- infection

- inflammation

- side effects of chemotherapy, radiation treatment or surgery

- inactivity and stiffness

- depression and anxiety[1]

Recurrent pain

Recurrent pain is pain that arises periodically and can result in absences from school, outside activities, etc. This type of pain may be the most common.

Descriptions are:

- periodic instead of persistent

- consisting of tension and migraine headaches

- abdominal pains

- chest pain and limb pains[5]

Chronic pain

Chronic pain in children is unresolved pain that affects activities of daily living and may result in a significant amount of missed school days. It is characterized as mild to severe and is present for long periods of time.[1] Chronic pain can develop from disease or injury with acute pain. Some have described chronic pain as the pain experienced when the child reports a headache, abdominal pain, back pain, generalized pain or combinations of these.[5] Children that experience chronic pain can have psychological effects. In addition, families may also suffer emotionally when the child experiences pain. Caring for a child in pain does have social consequences related to the disability and limitations that accompany the pain. In regards to outside factors, finding solutions for children in pain may generate additional costs from healthcare and lost wages because of the necessary time off from work.

Causes

The causes of pain children are similar to causes of pain in adults.

Pain can be experienced in many ways and is dependent upon the following factors in each child:

- prior painful episodes or treatments

- age and developmental stage

- disease or type of trauma

- personality

- culture

- socioeconomic status

- presence of family members and family dynamics.[15]

Assessment

Ongoing and frequent assessment between all those involved in the treatment plan is documented in a readily accessible format - usually the patient record.[4] Assessment of the pain in children depends upon the cooperation and developmental stage of the child. Some children do not have the ability to assist in their assessment because they have not matured enough cognitively, emotionally, or physically.[15]

Younger infants

Signs of distress and possible pain are exhibited by :

- inability to distinguish the stimulus from the pain

- ability to exhibit a reflexive response to pain

- expressions of pain

- tightly closed eyes[5]

- open mouth resembling a square rather than an oval or circle

- lowered eyebrows and tightly drawn together

- rigid body

- thrashing

- loud crying[15]

- increase in heart rate, even while sleeping

Older infants

Signs of distress and pain are exhibited by:

- deliberate withdrawal from pain and possible guarding

- loud crying

- painful facial expressions [15]

Toddlers

A toddler can express distress and pain by:

- expressing pain verbally

- thrashing extremities

- crying loudly

- screaming

- being uncooperative

- pushing away perceived source of pain (palpation)

- anticipating a pain-inducing procedure or event

- requesting to be comforted

- clinging to a significant person, possibly the one perceived as being protective[15]

School-aged children

School-aged children express pain (similar to toddlers) by:

- anticipating the pain but less intensively, understands concepts of time, i.e., imminent vs future pain

- stalling, trying to talk out of the situation where pain is anticipated

- having muscular rigidity[15]

Adolescent

Adolescents express pain by:

- with muscle tension, but with control

- with verbal expressions and descriptions[15]

Quantitative pain assessment

Although pain is subjective and is considered to exist as a spectrum rather than an exact determination, different assessment tools compare pain levels over time. This kind of assessment incorporates pain scales and requires a high enough developmental level so that the child can respond to the question(s).[15] A verbal response is not always necessary to quantify the pain.

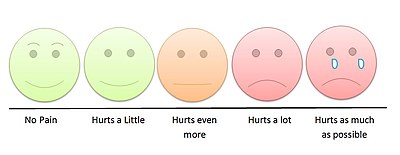

Pain scales

A pain scale measures a patient's pain intensity and other features. Pain scales are based on self-report, observational (behavioral), or physiological data. Self-report is considered primary and should be obtained if possible. Pain measurements help determine the severity, type, and duration of the pain. They are also used to construct an accurate diagnosis, determine a treatment plan, and evaluate the effectiveness of treatment. Pain scales are available for neonates, infants, children, adolescents, adults, seniors, and persons with impaired communication. Pain assessments are often regarded as "the 5th Vital Sign".[16]

| Self-report | Observational | Physiological | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant | — | Premature Infant Pain Profile; Neonatal/Infant Pain Scale | — |

| Child | Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale – Revised;[17] Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale; Coloured Analogue Scale[18] | FLACC (Face Legs Arms Cry Consolability Scale); CHEOPS (Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale)[19] | Comfort |

| Adolescent | Visual Analog Scale (VAS); Verbal Numerical Rating Scale (VNRS); Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS); Brief Pain Inventory | — | — |

During treatment

Clinicians responsible for a child, monitor the child frequently in tertiary care centers (hospitals). Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are used to manage the pain. Parents or caregivers are also requested to provide their own pain assessments. At the beginning of pharmacological treatment, clinicians monitor the child for adverse reactions to the medications. The levels of some medications are monitored to ensure that the child is not over-medicated or receives toxic levels of the drug. The levels also provide results that indicate that the levels in the blood are high enough to be effective in managing the pain. Medications are metabolized differently between children of the same age. Factors that influence the levels of medications controlling pain are the height, weight, and body surface of the child in addition to any other illnesses that a child might have.[15] Some medications may have a paradoxical effect in children, which is an effect that is the opposite of the expected effect. Clinicians monitor this and any other reactions to the medication.[20][21]

Because children process information differently than adults, atraumatic measures are used to reduce anxiety and stress. Treatment centers for children often employ these procedures.

Examples are:

- allowing the parent or caregiver to be present for painful procedures

- using a treatment room for painful procedures to ensure that the child's room is a place where little pain can be expected

- establish other 'pain-free zones' where no medical procedures are allowed (such as a playroom)

- offering choices to the child to give them some control over the procedures

- modelling procedures with dolls and toys

- using age-appropriate vocabulary and anatomical terms the child can understand.[15]

Non-pharmacological pain management

Pain-relieving, non-pharmacological management of discomfort during immunizations include putting sugar on a pacifier, comforting the child during and after the injections, chest-to-chest hugging, and giving the child choices on injection sites.[11] Other non-pharmacological treatments that have been found to be effective include:

- careful explanations of the procedure with pictures or other visual aids

- allow the child to ask questions of medical staff

- tour the place where the procedures will occur

- older children may benefit from watching a video that explains the procedure

- small children can play with dolls or other toys with a clinician to understand the procedure

- hypnosis and imagery with a psychologist or medical doctor can help with techniques that narrow the focus of the child

- distraction with songs, stories, toys, color, videos, TV, or music

- relaxation techniques such as deep breathing or massages[1]

Pharmacotherapy

The use of medications to treat acute, chronic, recurrent and neuropathic pain is most common. Most instances of pain in children are treated with analgesics. These include acetaminophen, NSAIDs, local anesthetics, opioids, and medications for neuropathic pain.[5] The most effective approach to pain management in children is to provide medicine around the clock instead of providing pain relief as needed. Regional anesthesia is also effective and recommended whenever possible. Opioids are effective too but often depress breathing in infants.[5]

Chronic pain treatment

Chronic pain is treated with a variety of medications and non-pharmacological interventions. Opioid tolerance and withdrawal can be seen in the NICU and PICU. Other side effects with opioid use can be: cognition deficits, altered mood, and disturbances of endocrine development. Opioid misuse can occur in adolescents and is associated with the use of alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana.[5]

Non-pharmacological treatment for children in helping to relieve periodic pain episodes and severity includes counselling and behavior modification therapy.[5] The American Association of Pediatrics have suggested that parents be educated on providing round the clock medication administration after their children receive surgery.[22]

Acute pain treatment

For acute pain, multiple medications given at the same time is proven to be most effective. This results in lower pain scores, provides greater relief, allows lower dosing (and side effects), targets different nerve pathways, and can be tailored to the child.[23][5]

Cancer pain treatment

Cancer pain is managed differently in children. Clinicians treating cancer pain can come from a variety of disciplines or specialties. Typically, medical history, physical examinations, age and overall health of the child is evaluated. The type of cancer may influence decisions about pain management. The extent of the cancer, the tolerance of the child to specific medications, procedure or therapies is also taken into account. The preferences of the parent or caregiver contribute to the determining of the best way to treat cancer pain.[1] For cancer pain, opioids are helpful and can be taken orally. The side effects are: constipation, fatigue, and disorientation. Others are given IV, subcutaneous, or trans-dermal. Switching medications may be necessary at times. Dosing for children is based upon studies with adults or short-term studies. Children can develop opioid tolerance where larger doses are needed to have the same effect. When resistance to opioids develop, the pain responsiveness is reset and pain increases. Tolerance is likely to develop in younger children.[5]

History

In the past, it was believed that the expressions of pain in babies was reflexive and due to the immaturity of the infant brain, the pain could not really be perceived.[24] Attempting to relieve pain in infants was considered futile since it was thought to be impossible to measure the child's pain.[25]

These beliefs along with cultural concerns of opiate addiction contributed to the clinicians decision to withhold pain relief.[26]

In 1994, responding to the need for a more useful system for describing chronic pain, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) classified pain by the:

- region of the body involved (e.g. abdomen, lower limbs),

- system whose dysfunction may be causing the pain (e.g., nervous, gastrointestinal),

- duration and pattern of occurrence,

- intensity and time since onset, and

- cause[27] This system was criticized by Clifford J. Woolf and others as inadequate for guiding treatment.[28]

Woolf suggested three categories of pain:

- nociceptive pain,

- inflammatory pain which is associated with tissue damage and the infiltration of immune cells, and

- pathological pain which is a disease state caused by damage to the nervous system or by its abnormal function (e.g. fibromyalgia, peripheral neuropathy, tension type headache, etc.).[29]

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Pain Management and Children". Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford Children's Health. 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Medical Definition of Pain". Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Verghese, Susan T; Hannallah, Raafat S (15 July 2010). "Acute pain management in children". Journal of Pain Research. 3: 105–123. PMC 3004641. PMID 21197314.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Health, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family; Task Force on Pain in Infants, Children (1 September 2001). "The Assessment and Management of Acute Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 108 (3): 793–797. doi:10.1542/peds.108.3.793. PMID 11533354 – via pediatrics.aappublications.org.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Berde, Charles. "Pharmacotherapy of Pain in Infants and Children" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ Twycross, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Twycross, p. 7.

- ^ Twycross & page 7.

- ^ Twycross, p. 140.

- ^ Twycross, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Managing Your Child's Pain While Getting a Shot". HealthyChildren.org. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Twycross, p. 1.

- ^ twycross, p. 3.

- ^ Twycross, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Henry, p. 43.

- ^ "Pain: current understanding of assessment, management and treatments" (PDF). Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations andnthe National Pharmaceutical Council, Inc. December 2001. Retrieved January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The Faces Pain Scale – Revised". Pediatric Pain Sourcebook of Protocols, Policies and Pamphlets. 7 August 2007.

- ^ Stinson, JN; Kavanagh, T; Yamada, J; Gill, N; Stevens, B (November 2006). "Systematic review of the psychometric properties, interpretability and feasibility of self-report pain intensity measures for use in clinical trials in children and adolescents". Pain. 125 (1–2): 143–57. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.006. PMID 16777328.

- ^ von Baeyer, C.L.; Spagrud, L.J. (2007). "Systematic review of observational (behavioral) measures of pain for children and adolescents aged 3 to 18 years". Pain. 127 (1–2): 140–150. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.014. PMID 16996689.

- ^ Moon, Young Eun (2013). "Paradoxical reaction to midazolam in children". Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. 65 (1): 2. doi:10.4097/kjae.2013.65.1.2. ISSN 2005-6419.

- ^ Mancuso, Carissa E.; Tanzi, Maria G.; Gabay, Michael (2004). "Paradoxical Reactions to Benzodiazepines: Literature Review and Treatment Options". Pharmacotherapy. 24 (9): 1177–1185. doi:10.1592/phco.24.13.1177.38089. ISSN 0277-0008.

- ^ Fortier, Michelle A.; MacLaren, Jill E.; Martin, Sarah R.; Perret-Karimi, Danielle; Kain, Zeev N. (1 October 2009). "Pediatric Pain After Ambulatory Surgery: Where's the Medication?". Pediatrics. 124 (4): e588–e595. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3529. PMID 19736260. Retrieved 20 August 2017 – via pediatrics.aappublications.org.

- ^ Twycross, p. 147.

- ^ Chamberlain DB (1989). "Babies Remember Pain". Pre- and Peri-natal Psychology. 3 (4): 297–310.

- ^ Wagner AM (July 1998). "Pain control in the pediatric patient". Dermatol Clin. 16 (3): 609–17. doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70256-4. PMID 9704215.

- ^ Mathew PJ, Mathew JL (2003). "Assessment and management of pain in infants". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 79 (934): 438–443. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.934.438. PMC 1742785. PMID 12954954.

- ^ Classification of Chronic Pain. 2 ed. Seattle: International Association for the Study of Pain; 1994. ISBN 0-931092-05-1. p. 3 & 4.

- ^ Towards a mechanism-based classification of pain?. Pain. 1998;77(3):227–9. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00099-2. PMID 9808347.

- ^ What is this thing called pain?. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(11):3742–4. doi:10.1172/JCI45178. PMID 21041955.

Bibliography

- Henry, Norma (2016). RN nursing care of children : review module. Stilwell, KS: Assessment Technologies Institute. ISBN 9781565335714.

- Roberts, Michael (2017). Handbook of pediatric psychology. New York: The Guilford Press. ISBN 9781462529780.

- Twycross, Alison (2014). Managing pain in children : a clinical guide for nurses and healthcare professionals. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 9780470670545.