Parks–McClellan filter design algorithm

This article needs attention from an expert in Signal Processing. See the talk page for details. (July 2014) |

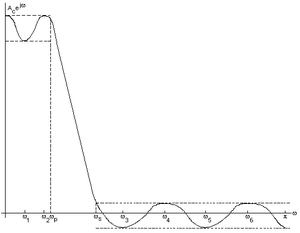

The y-axis is the frequency response H(ω) and the x-axis are the various radian frequencies, ωi. It can be noted that the two frequences marked on the x-axis, ωp and ωs. ωp indicates the pass band cutoff frequency and ωs indicates the stop band cutoff frequency. The ripple like plot on the upper left is the pass band ripple and the ripple on the bottom right is the stop band ripple. The two dashed lines on the top left of the graph indicate the δp and the two dashed lines on the bottom right indicate the δs. All other frequencies listed indicate the extremal frequencies of the frequency response plot. As a result, there are six extremal frequencies, and then we add the pass band and stop band frequencies to give a total of eight extremal frequencies on the plot.

The Parks–McClellan algorithm, published by James McClellan and Thomas Parks in 1972, is an iterative algorithm for finding the optimal Chebyshev finite impulse response (FIR) filter. The Parks–McClellan algorithm is utilized to design and implement efficient and optimal FIR filters. It uses an indirect method for finding the optimal filter coefficients.

The goal of the algorithm is to minimize the error in the pass and stop bands by utilizing the Chebyshev approximation. The Parks–McClellan algorithm is a variation of the Remez exchange algorithm, with the change that it is specifically designed for FIR filters. It has become a standard method for FIR filter design.

History of optimal FIR filter design[edit]

In the 1960s, researchers within the field of analog filter design were using the Chebyshev approximation for filter design. During this time, it was well known that the best filters contain an equiripple characteristic in their frequency response magnitude and the elliptic filter (or Cauer filter) was optimal with regards to the Chebyshev approximation. When the digital filter revolution began in the 1960s, researchers used a bilinear transform to produce infinite impulse response (IIR) digital elliptic filters. They also recognized the potential for designing FIR filters to accomplish the same filtering task and soon the search was on for the optimal FIR filter using the Chebyshev approximation.[1]

It was well known in both mathematics and engineering that the optimal response would exhibit an equiripple behavior and that the number of ripples could be counted using the Chebyshev approximation. Several attempts to produce a design program for the optimal Chebyshev FIR filter were undertaken in the period between 1962 and 1971.[1] Despite the numerous attempts, most did not succeed, usually due to problems in the algorithmic implementation or problem formulation. Otto Herrmann, for example, proposed a method for designing equiripple filters with restricted band edges.[1] This method obtained an equiripple frequency response with the maximum number of ripples by solving a set of nonlinear equations. Another method introduced at the time implemented an optimal Chebyshev approximation, but the algorithm was limited to the design of relatively low-order filters.[1]

Similar to Herrmann's method, Ed Hofstetter presented an algorithm that designed FIR filters with as many ripples as possible. This has become known as the Maximal Ripple algorithm. The Maximal Ripple algorithm imposed an alternating error condition via interpolation and then solved a set of equations that the alternating solution had to satisfy.[1] One notable limitation of the Maximal Ripple algorithm was that the band edges were not specified as inputs to the design procedure. Rather, the initial frequency set {ωi} and the desired function D(ωi) defined the pass and stop band implicitly. Unlike previous attempts to design an optimal filter, the Maximal Ripple algorithm used an exchange method that tried to find the frequency set {ωi} where the best filter had its ripples.[1] Thus, the Maximal Ripple algorithm was not an optimal filter design but it had quite a significant impact on how the Parks–McClellan algorithm would formulate.

History[edit]

In August 1970, James McClellan entered graduate school at Rice University with a concentration in mathematical models of analog filter design and enrolled in a new course called "Digital Filters" due to his interest in filter design.[1] The course was taught jointly by Thomas Parks and Sid Burrus. At that time, DSP was an emerging field and as a result lectures often involved recently published research papers. The following semester, the spring of 1971, Thomas Parks offered a course called "Signal Theory," which McClellan took as well.[1] During spring break of the semester, Parks drove from Houston to Princeton in order to attend a conference, where he heard Ed Hofstetter's presentation about a new FIR filter design algorithm (Maximal Ripple algorithm). He brought the paper by Hofstetter, Oppenheim, and Siegel, back to Houston, thinking about the possibility of using the Chebyshev approximation theory to design FIR filters.[1] He heard that the method implemented in Hofstetter's algorithm was similar to the Remez exchange algorithm and decided to pursue the path of using the Remez exchange algorithm. The students in the "Signal Theory" course were required to do a project and since Chebyshev approximation was a major topic in the course, the implementation of this new algorithm became James McClellan's course project. This ultimately led to the Parks–McClellan algorithm, which involved the theory of optimal Chebyshev approximation and an efficient implementation. By the end of the spring semester, McClellan and Parks were attempting to write a variation of the Remez exchange algorithm for FIR filters. It took about six weeks to develop and some optimal filters had been designed successfully by the end of May.

The algorithm[edit]

The Parks–McClellan Algorithm is implemented using the following steps:[1]

- Initialization: Choose an extremal set of frequences {ωi(0)}.

- Finite Set Approximation: Calculate the best Chebyshev approximation on the present extremal set, giving a value δ(m) for the min-max error on the present extremal set.

- Interpolation: Calculate the error function E(ω) over the entire set of frequencies Ω using (2).

- Look for local maxima of |E(m)(ω)| on the set Ω.

- If max(ω∈Ω)|E(m)(ω)| > δ(m), then update the extremal set to {ωi(m+1)} by picking new frequencies where |E(m)(ω)| has its local maxima. Make sure that the error alternates on the ordered set of frequencies as described in (4) and (5). Return to Step 2 and iterate.

- If max(ω∈Ω)|E(m)(ω)| ≤ δ(m), then the algorithm is complete. Use the set {ωi(0)} and the interpolation formula to compute an inverse discrete Fourier transform to obtain the filter coefficients.

The Parks–McClellan Algorithm may be restated as the following steps:[2]

- Make an initial guess of the L+2 extremal frequencies.

- Compute δ using the equation given.

- Using Lagrange Interpolation, we compute the dense set of samples of A(ω) over the passband and stopband.

- Determine the new L+2 largest extrema.

- If the alternation theorem is not satisfied, then we go back to (2) and iterate until the alternation theorem is satisfied.

- If the alternation theorem is satisfied, then we compute h(n) and we are done.

To gain a basic understanding of the Parks–McClellan Algorithm mentioned above, we can rewrite the algorithm above in a simpler form as:

- Guess the positions of the extrema are evenly spaced in the pass and stop band.

- Perform polynomial interpolation and re-estimate positions of the local extrema.

- Move extrema to new positions and iterate until the extrema stop shifting.

Explanation[edit]

The picture above on the right displays the various extremal frequencies for the plot shown. The extremal frequencies are the maximum and minimum points in the stop and pass bands. The stop band ripple is the lower portion of ripples on the bottom right of the plot and the pass band ripple is the upper portion of the ripples on the top left of the plot. The dashed lines going across the plot indicate the δ or maximum error. Given the positions of the extremal frequencies, there is a formula for the optimum δ or optimum error. Since we do not know the optimum δ or the exact positions of the extrema on the first attempt, we iterate. Effectively, we assume the positions of the extrema initially, and calculate δ. We then re-estimate and move the extrema and recalculate δ, or the error. We repeat this process until δ stops changing. The algorithm will cause the δ error to converge, generally within ten to twelve iterations.[3]

Additional notes[edit]

Before applying the Chebyshev approximation, a set of steps were necessary:

- Define the set of basis function for the approximation, and

- Exploit the fact that the pass and stop bands of bandpass filters would always be separated by transition regions.[1]

Since FIR filters could be reduced to the sum of cosines case, the same core program could be used to perform all possible linear-phase FIR filters. In contrast to the Maximum Ripple approach, the band edges could now be specified ahead of time.

To achieve an efficient implementation of the optimal filter design using the Parks-McClellan algorithm, two difficulties have to be overcome:

- Defining a flexible exchange strategy, and

- Implementing a robust interpolation method.[1]

In some sense, the programming involved the implementation and adaptation of a known algorithm for use in FIR filter design. Two faces of the exchange strategy were taken to make the program more efficient:

- Allocating the extremal frequencies between the pass and stop bands, and

- Enabling movement of the extremals between the bands as the program iterated.[1]

At initialization, the number of extremals in the pass and stop band could be assigned by using the ratio of the sizes of the bands. Furthermore, the pass and stop band edge would always be placed in the extremal set, and the program's logic kept those edge frequencies in the extremal set. The movement between bands was controlled by comparing the size of the errors at all the candidate extremal frequencies and taking the largest. The second element of the algorithm was the interpolation step needed to evaluate the error function. They used a method called the Barycentric form of Lagrange interpolation, which was very robust.

All conditions for the Parks–McClellan algorithm are based on Chebyshev's alternation theorem. The alternation theorem states that the polynomial of degree L that minimizes the maximum error will have at least L+2 extrema. The optimal frequency response will barely reach the maximum ripple bounds.[3] The extrema must occur at the pass and stop band edges and at either ω=0 or ω=π or both. The derivative of a polynomial of degree L is a polynomial of degree L−1, which can be zero at most at L−1 places.[3] So the maximum number of local extrema is the L−1 local extrema plus the 4 band edges, giving a total of L+3 extrema.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m McClellan, J.H.; Parks, T.W. (2005). "A personal history of the Parks-Mc Clellan algorithm". IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 22 (2): 82–86. Bibcode:2005ISPM...22...82M. doi:10.1109/MSP.2005.1406492. S2CID 15400093.

- ^ Jones, Douglas (2007), Parks–McClellan FIR Filter Design, retrieved 2009-03-29

- ^ a b c Lovell, Brian (2003), Parks–McClellan Method (PDF), retrieved 2009-03-30

Additional references[edit]

The following additional links provide information on the Parks–McClellan Algorithm, as well as on other research and papers written by James McClellan and Thomas Parks:

- Chebyshev Approximation for Nonrecursive Digital Filters with Linear Phase

- Short Help on Parks–McClellan Design of FIR Low Pass Filters Using MATLAB

- Intro to DSP

- The MathWorks MATLAB documentation

- ELEC4600 Lecture Notes (original link, archived on 15 Apr 2012)

- C Code Implementation (LGPL License) – By Jake Janovetz

- Iowa Hills Software. "Example C Code". Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Revised and expanded algorithm McClellan, Parks, & Rabiner, 1975; Fortran code.