Revenge tragedy

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (September 2017) |

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (September 2017) |

Revenge tragedy (less commonly referred to as revenge drama, revenge play, or tragedy of blood) defines a genre of plays made popular in early modern England. Ashley H. Thorndike formally established this genre in his seminal 1902 article "The Relations of Hamlet to Contemporary Revenge Plays," which characterizes revenge tragedy "as a tragedy whose leading motive is revenge and whose main action deals with the progress of this revenge, leading to the death of the murderers and often the death of the avenger himself."[1]

Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy (c.1580s) is often considered the inaugural revenge tragedy on the early modern stage. However, more recent research extends early modern revenge tragedy to the 1560s with poet and classicist Jasper Heywood's translations of Seneca at Oxford University, including Troas (1559), Thyestes (1560), and Hercules Furens (1561).[2] Additionally, Thomas Norton and Thomas Sackville's play Gorbuduc (1561) is considered an early revenge tragedy (almost twenty years prior to The Spanish Tragedy). Other well-known revenge tragedies include William Shakespeare's Hamlet (c.1599-1602) and Titus Andronicus (c.1588-1593) and Thomas Middleton's The Revenger's Tragedy (c.1606).

Revenge tragedy as a genre

The genre of revenge tragedy is a modern invention, developed as a means to talk about early modern tragedies that maintain a theme or motif of revenge in varying degrees. Classification of the revenge tragedy is at times contentious, as with other early modern theatrical genres.

Lawrence Danson suggests that Shakespeare and his contemporaries had a "healthy ability to live comfortably with the unruliness of a theatre where genre was not static but moving and mixing, always producing new possibilities."[3] On the contrary, Shakespeare's 1623 First Folio's frontispiece famously depicts the printer-imposed (Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount) three genres of comedy, history, and tragedy, which can erroneously lead readers to believe that plays are easily categorized and contained.[4] While these three genres have remained staples in discussions of genre, other genres are often either invoked or created to accommodate the generic slipperiness of early modern drama.[citation needed] These include not only revenge tragedy, but also city comedy, romance, pastoral, and problem play, among others. It has become common to consider any tragedy that maintains an element of revenge in it a revenge tragedy.[citation needed] Lily Campbell argues that revenge is the great thematic uniter of all early modern tragedy, and "all Elizabethan tragedy must appear as fundamentally a tragedy of revenge if the extent of the idea of revenge be but grasped."[5] Fredson Bowers's work (1959) on the genre not only widened and complicated what revenge tragedy is, but also augmented its function as a productive lens in the work of dramatic and dramaturgical interpretation.[citation needed] A revenge tragedy thus can also be any tragedy where revenge is, more or less, a minor part of the overall narrative, rather than just a narrative's major driving force. As long as revenge is an underlying theme or motivation throughout the piece, it can be labeled as revenge tragedy.

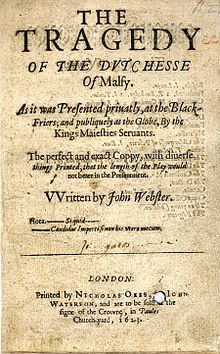

For example, John Webster's The Duchess of Malfi (c.1613), while often classified as a tragedy (its original frontispiece marketed it as The Tragedy of the Dutchesse of Malfy), can also be classified or read as a revenge tragedy, since both major and minor characters are motivated by revenge. Likewise, Titus Andronicus was originally marketed in the First Folio as The Lamentable Tragedy of Titus Andronicus. Hamlet was similarly titled in the First Folio as The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke and The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke in the Second Quarto edition (1604). It is not unusual, then, to find present-day editors classifying these plays as tragedies;[6][7] however, it is becoming increasingly common to also read and interpret early modern drama with other genres in mind, such as revenge tragedy.[citation needed]

Generic conventions

While these conventions don't apply to all plays that can be read as revenge tragedies, the events on this list commonly take place within the genre:

- The avenger is killed

- Spectacle for the sake of spectacle

- Villains and accomplices that assist the avenger are killed

- The supernatural (often in the form of a ghost who urges the protagonist to enact vengeance)

- A play within a play, or dumb show

- Madness or feigned madness

- Disguise

- Violent murders, including decapitation and dismemberment

- Soliloquies

- A Machiavellian figure

- Cannibalism (Thyestean banquets)

- A fifth and final act where many characters are killed (multiple corpses on the stage)

- Degeneration of a once-noble protagonist

- In later Jacobean and Caroline revenge tragedies, the protagonist is more often a villain than a hero (though this is subjective)

- In later revenge tragedies, there is often more than one character seeking revenge

Significant revenge tragedy playwrights

Lucius Seneca

Lucius Seneca was a prominent playwright of the first century, famous for helping shape the genre of revenge tragedy with his ten plays: Hercules Furens, Troades, Phoenissae, Medea, Phaedra, Oedipus, Agamemnon, Thyestes, Hercules Oetaeus, and Octavia.[8] The importance of his plays lies in the difficulty of the time period. While Elizabethan tragedy was considered more acceptable, revenge tragedy sought to unleash the carnal side of human nature on stage in a much more grotesque way. It was a transitional time in the literary world that would eventually lead to grueling pieces. Infamous scenes like the cannibalistic feast in Thyestes introduce the audience to another dimension of the human experience, challenging them to reflect on extreme emotions and dig deeper into the conventions of the genre.[citation needed]

Seneca’s Thyestes, a tale of revenge and horror with prominent cannibalism, can be identified as one of the first "revenge pieces." In the power struggle between two brothers, Atreus and Thyestes, there is a clear theme of revenge. The underlying story of the plot is that Thyestes has had an affair with Atreus' wife, stolen his golden fleece, and sneakily taken the throne of Mycenae from him. After a long period of exile, Thyestes is allowed to return to Rome. However, the conflict escalates when Atreus executes his revenge by tricking Thyestes into eating his own children. Although overtly grotesque, this piece of literature follows the conventions of the revenge tragedy genre. Ultimately, everyone ends up dead and revenge has been taken to a level that would not be anticipated in the beginning.[citation needed]

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright from the 16th century.[9] Through plays as Hamlet and Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare portrayed the basic characteristics of revenge tragedy. He presented elements that are quite similar to those from Seneca's tragedies, establishing tragedy as a more known genre.

Titus Andronicus depicts the madness of Titus, who wanted to take revenge on Tamora and her sons for what they did to Lavinia and Bassianus. This leads him to kill everybody that he faced in his search to satisfy himself, avenging them. The main plot focuses on Titus's revenge against Tamora and her sons, but also there are other people on whom he seeks vengeance. This is an element that is defined in revenge tragedy.[citation needed] The appearance of cannibalism in the last scene at the banquet and grotesque elements during the play relate Titus Andronicus to Seneca's earlier revenge tragedies.

Gender controversy and female sexuality

The gender of a character who commits revenge in a revenge tragedy play can be significant when criticizing such works. In the play Titus Andronicus, for example, men are bold enough to carry out their own revenge, or take revenge for another. Because they not only carry out their own revenge, but also revenge on behalf of others, the men are portrayed as superior.[10] Women, however, get their revenge through controlling others. In Titus Andronicus, Tamora, Queen of the Goths, uses her power to make the people around do her work, including her own sons. The women in these plays are shown as powerful, but only in the sense that they can use others for their own benefit. Additionally, women are often depicted as the cause for a male protagonist's revenge. Tamora and Lavinia both push Titus to the edge over the course of the play, Tamora by committing injustices and by letting her sons mutilate Titus' daughter, Lavinia, and Lavinia by then having to live her life in shame. In the end of Titus Andronicus, Titus pretends to be ignorant to Tamora's schemes, but in reality, it is Tamora who is ignorant to the real reason Titus begins to behave nicely. Throughout these plays, women are portrayed as weaker and easier to be fooled.[citation needed]

Sexual persuasion is another common method through which female characters execute their revenge and a primary source of conflict within the genre. A female character is often portrayed as one of two extremes: either she is the promiscuous manipulator or a delicate virgin. The value of women in these plays is linked to their chastity. In Titus Andronicus, Tamora, empress of Rome, is an explicitly sexualized character who can only attempt revenge by manipulating the men in her life, using them as pawns. Lavinia, daughter of Titus, is portrayed as a pure doe who loses her value upon being ravished. The presentation of female sexuality in these plays is therefore a source of controversy. However, more recent works in the genre present female characters whose measure can be valued by more than just their sexuality.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Thorndike, A. H. "The Relations of Hamlet to Contemporary Revenge Plays." Modern Language Association. 17.2 (1902): 125-220. Print.

- ^ Irish, Bradley J. "Vengeance, Variously: Revenge before Kyd in Early Elizabethan Drama." Early Theatre. 12.2 (2009): 117-134. Print.

- ^ Danson, Lawrence. Shakespeare's Dramatic Genres. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 2000. Print. p. 11.

- ^ The First Folio, printed posthumously, was also prepared by Shakespeare's colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell.

- ^ Campbell, Lily. "Theories of Revenge in Renaissance England." Modern Philology. 28.3 (1931) 281-296. Print.

- ^ Engle, Lars. Introduction to The Duchess of Malfi. The Duchess of Malfi. By John Webster. English Renaissance Drama. Eds. David Bevington, et al. Norton, New York: 2002. 1749-1754. Print. p. 1749.

- ^ Weis, Rene. Introduction. John Webster: The Duchess of Malfi and Other Plays. By John Webster. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1996. ix-xxviii. Print. p. xxiii

- ^ Alkhaleefah, Tarek A. "The Senecan Tragedy and its Adaptation for the Elizabethan Stage: A Study of Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy." International Journal of English and Literature6.9 (Sept. 2015): 163-167. Print.

- ^ Alchin, Linda K. "William Shakespeare". William Shakespeare. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Green, Douglas E. (Autumn 1989). "Interpreting "Her Martyr'd Signs": Gender and Tragedy in Titus Andronicus". Shakespeare Quarterly. 40: 317. doi:10.2307/2870726.