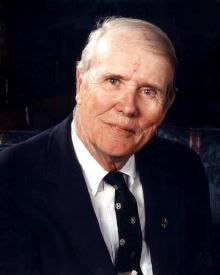

Robert Ridder

Robert Ridder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 21, 1919 New York City, US |

| Died | June 24, 2000 (aged 80) |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Known for | Ice hockey administrator Knight Ridder media Philanthropist |

| Spouse | Kathleen Ridder |

| Family | Victor F. Ridder (father) Herman Ridder (grandfather) |

| Awards | Lester Patrick Trophy U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame IIHF Hall of Fame |

Robert Blair Ridder (July 21, 1919 – June 24, 2000) was an American ice hockey administrator, media businessman, and philanthropist. He was the founding president of the Minnesota Amateur Hockey Association, and managed the United States men's national ice hockey team at the 1952 and 1956 Olympics. He was a director in the Knight Ridder media company which controlled several television and radio stations, and newspapers in Minnesota. His wealth allowed him to be a founding owner of the Minnesota North Stars and helped him provide funding for the construction of Ridder Arena at the University of Minnesota. For his work in hockey in the United States, he received the Lester Patrick Trophy, and was inducted into the United States Hockey Hall of Fame and the IIHF Hall of Fame.

Early life

Robert Blair Ridder was born on July 21, 1919, in New York City.[1][2] He was the fifth of seven children to parents Victor F. Ridder and Marie Thompson, and the grandson of Herman Ridder.[3] As a youth he became interested in hockey attending New York Rangers games at the Old Madison Square Garden.[4] He graduated from Harvard University,[1][2][5] and served in the United States Coast Guard during World War II.[6] He married Kathleen Culman and moved to Duluth, Minnesota in 1943.[7][8]

Hockey career

Ridder began his ice hockey career in 1943 with the Duluth Heralds, an amateur senior ice hockey team in the Duluth Industrial Hockey League.[4] He felt that Minnesota needed a state-level organization to oversee hockey and help grow the sport.[1][5] Ridder called a meeting in Saint Paul in October 1947, and founded what became the Minnesota Amateur Hockey Association (MAHA).[4] He served as the first president of the MAHA from 1947 to 1949, and began the process of affiliating with a national body.[4][9] In December 1947, the MAHA was formally accepted as a member of the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States (AHAUS), becoming the first state association to do so.[4] The MAHA grew quickly and trailed behind only the Ontario Hockey Association, and the Quebec Amateur Hockey Association, in the number of registered players in North America.[1][5]

Ridder successfully lobbied the International Ice Hockey Federation to recognize AHAUS as the group responsible to represent the United States in ice hockey at the Olympic Games,[2] and was also able to organize and finance the United States men's national ice hockey team.[1][5] He was the manager of the American team in Oslo at the 1952 Winter Olympics, which resulted in a silver medal and a second place finish behind Canada. He returned to manage the American team in Cortina d'Ampezzo at the 1956 Winter Olympics, which resulted in another silver medal and a second-place behind the Soviet Union.[1][2][5]

Ridder was one of the eight original co-owners of the Minnesota North Stars. His group paid the $2 million expansion fees in the 1967 NHL expansion to bring a National Hockey League team to the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area.[10][11]

Media business

Ridder worked in the family business Ridder Publications, which merged into the Knight Ridder media company.[7][12] His media career began by reporting news for WEBC, and several newspapers in the Minnesota area including the Duluth News Tribune, Grand Forks Herald, Saint Paul Dispatch, and the St. Paul Pioneer Press. He purchased WDSM radio in 1948, and became its president.[6][11] Ridder was the first in his family to buy into television, becoming president of WCCO-TV in 1949, and WCCO Radio in 1952.[6] He also served as the assistant secretary and director of Ridder Publications, he was vice president and director of Northwest Publications, Dispatch Realty, Aberdeen News and the Grand Forks Herald, and was a director of Mid-Continent Radio Television and Midwest Radio Television.[11]

Charitable work

Ridder volunteered with the American Red Cross, the Saint Paul Urban League, and the Saint Paul United Fund.[6] He served on the USA Hockey Foundation, and was a director for its Hall of Fame.[1][2][5] He was a co-chair of the task force to build a women's-only hockey arena at the University of Minnesota.[11] Ridder and his wife contributed $500,000 towards the construction of Ridder Arena, dedicated to the Minnesota Golden Gophers women's ice hockey team, but he died before its completion.[13][14]

Later life and honors

Ridder died on June 24, 2000, at his home in Mendota Heights, Minnesota.[10][11][6] He had been married for 56 years and had four children.[15]

Ridder received the AHAUS citation award in 1967, for of contributions towards American amateur hockey[16] He was inducted into the United States Hockey Hall of Fame in 1976.[2][10] He received the Lester Patrick Trophy during the 1993–94 NHL season, in recognition of his contribution to ice hockey in the United States.[17][18] He was inducted into the IIHF Hall of Fame in 1998, in the builder category.[10][19] He was posthumously inducted in the inaugural class of the Minnesota Broadcasting Hall of Fame in 2001.[6] The American Hockey Coaches Association recognized Ridder and his widow in 2009 with the Joe Burke Award, for dedication to women's ice hockey.[13][20] The University of Minnesota awards the "Kathleen C. and Robert B. Ridder Scholarship" annually to a student athlete on the Golden Gophers women's ice hockey team.[13]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Robert Ridder". US Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "2.43 Bob Ridder". Legends of Hockey. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "Family Files Page 817". Genealogical Society of Bergen County. January 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Minnesota Amateur Hockey Association: The Early Years". Vintage Minnesota Hockey. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Robert Ridder Sr". US Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bob Ridder". Pavek Museum of Broadcasting. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Lerner, Laura (April 4, 2017). "Kathleen Ridder, champion of women in politics, dies at 94". Star Tribune. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Woltman, Nick (April 4, 2017). "Kathleen Ridder, U. of M. women's athletics booster, dies at 94". Twin Cities Pioneer Press. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Allen, Kevin (2011). Star-Spangled Hockey: Celebrating 75 Years of USA Hockey. Chicago, Illinois: Triumph Books. ISBN 9781633190870.

- ^ a b c d AP Staff writers (June 27, 2000). "Robert Blair Ridder, 80, Hockey Executive". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e AP Staff writers (June 26, 2000). "Media mogul was owner of hockey team". The Tribune-Democrat. Johnstown, Pennsylvania. p. 21.

- ^ "Kathleen Ridder leaves strong legacy in Minnesota and at Mitchell Hamline". Mitchell Hamline School of Law. April 5, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Minnesota Mourns Loss of Kathleen Ridder". University of Minnesota Athletics. April 5, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "Ridder Arena". Vintage Minnesota Hockey. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "Kathleen Culman Ridder Obituary". Dignity Memorial. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "Citation Award". USA Hockey. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ "Non-NHL Trophies – Lester Patrick Trophy". Legends of Hockey. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ "Lester Patrick Trophy Information and Winners". NHL.com. 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "IIHF Hall of Fame". International Ice Hockey Federation. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "AHCA Awards". American Hockey Coaches Association. 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- 1919 births

- 2000 deaths

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 20th-century American philanthropists

- American Red Cross personnel

- American sports executives and administrators

- Businesspeople from New York City

- Harvard University alumni

- Ice hockey people from Minnesota

- IIHF Hall of Fame inductees

- Lester Patrick Trophy recipients

- Military personnel from New York City

- Minnesota Golden Gophers women's ice hockey

- Minnesota North Stars executives

- National Hockey League owners

- People from Mendota Heights, Minnesota

- Philanthropists from Minnesota

- Philanthropists from New York (state)

- Ridder family

- Sportspeople from New York City

- Sportspeople from the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan area

- United States Coast Guard personnel of World War II

- United States Hockey Hall of Fame inductees

- USA Hockey