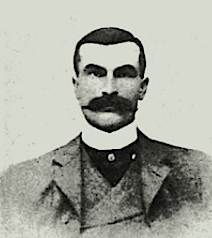

Selwyn Edge

Selwyn Francis Edge (1868–1940) was a British businessman, racing driver, cyclist and record-breaker. He is principally associated with selling and racing De Dion-Bouton, Gladiator; Clemént-Panhard, Napier and AC cars.[1]

Personal life

Edge was born in Concord township,[1] near Sydney, on 29 March 1868; his parents were Alexander Ernest Edge and Annie Charlotte Sharp.[2] At age three,[1] he was taken to London where in his teens he competed successfully as a bicycle racer, winning the North Road Cycling Club's 100 Mile Road Race in 1888[3] and the Westerham Hill climb when he was nineteen.[2] One of the English Team and aged 23 he came third in the first Bordeaux–Paris cycle race in 1891.[4] He worked for Rudge then Harvey Du Cros as manager of his new Dunlop offices in London.[2] In 1892 he married Eleanor Rose Sharp who died sometime before 1917; his second wife, Myra Caroline Martin, whom he married in 1917, had two daughters by him.[2]

From 1910 until at least 1922 he resided at Gallops Homestead, Ditchling, Sussex, and from 1912 to 1919, courtesy of his contract with Napiers, he devoted himself to farming.[5]

He died 12 February 1940 in Eastbourne, Sussex, England.[6]

Business career

In 1899, he went into partnership with pioneering motorist Charles Jarrott and Herbert Duncan to found De Dion-Bouton British and Colonial Ltd as importers of cars. He had become friends with Montague Napier (of Napier & Son), another keen cyclist, and in 1898 asked Napier to carry out some improvements to his Panhard. In 1899, along with Harvey du Cros, Edge formed the Motor Vehicle Company Ltd to sell these improved cars, made by Napiers (Edge paid £400, selling at £500),[7] as well as Gladiators and Clément-Panhards, both manufactured in Paris by Adolphe Clément-Bayard.[1]

In 1907 The Sydney Morning Herald reported: "S. F. Edge (1907), Ltd., has been registered at Somerset House, London, with a capital of £275,000, to carry on the business of motor car, cycle, launch, and flying machine manufacturers."[8] He sold his company, S.F. Edge Ltd, to Napier in 1912, for £120,000.[1] The sale included an agreement not to be involved in motor manufacturing for seven years. During this period he devoted himself to farming at Ditchling, Sussex.[5]

In 1917 he was appointed controller of the agricultural machinery department of the Ministry of Munitions.[6]

When the embargo on motor manufacturing expired in 1919 he started to build up a shareholding in AC Cars, gaining full control in 1922. About 1923 Edge was also managing director of William Cubitt & Company, who had entered the car market with the Cubitt marque, but were out of business by 1925.[9] Edge switched the contract for purchasing engines for the AC car from Anzani, where he also sat on the board, to Cubitt, who produced what was essentially a copy of the Anzani design.[10] Edge purchased AC cars outright for £135,000 in 1927.[11] When AC collapsed in 1929, Edge sold his interest in the company and took no further business interest in the motor industry.[1]

Motor racing

Recognizing the value of publicity gained from auto racing, which no other British marque did,[1] Edge entered an 8 hp (6 kW) four-cylinder Napier in the Automobile Club's 1900 Thousand Miles (1600 km) Trial of the Automobile Club on behalf of Edward Kennard; driven by Edge, with Kennard along, on a circuit from Newbury to Edinburgh and back, she won her class, being one of only thirty-five finishers (of sixty-four starters)[12] and one of just twelve to average the requisite 12 mph (19 km/h) in England and 10 mph (16 km/h) in Scotland.[13] He did the same (with C. S. Rolls his riding mechanic) at the 837 mi (1350 km) Paris-Toulouse-Paris rally in June; the car would be eliminated due to ignition trouble.[13]

In the 1901 Gordon Bennett Cup, Edge entered a special 17-litre Napier which he was only able to test en route because it had been completed on 25 May, only four days before the event. Montague Napier was the riding mechanic. The car was too powerful for the Dunlop tyres and fitting new French tyres led to disqualification, since they were not of the same national of origin.[13] In the concurrent Paris-Bordeaux rally, it retired with clutch trouble.[13]

For the 1902 Gordon Bennett, Edge's Napier was the sole British entrant; with his cousin, Cecil Edge, as riding mechanic, he won, at an average 31.8 mph (51.2 km/h) (though by default, since the French entrants all fell out).[13] The preparation of the car was hurried with some parts being fitted on the train to Paris. Additionally the second gear had not been hardened properly so, on arriving in Paris, Edge got the gear out, contacted his friend Adolphe Clément (Adolphe Clément-Bayard), borrowed his factory, hardened the gear, reassembled everything, and went on to win the race.[14]

At the 1903 Gordon Bennett, Edge had an 80 hp (60 kW) Napier, the Type K5, but was disqualified.[13] Edge (with Arthur McDonald, manager of Napiers' Genoa factory, as riding mechanic) fared no better with the K5 in the 1904 Gordon Bennett in Germany.

In 1903 Edge's eye for publicity created a world first when, on 2 October, Dorothy Levitt won her class at the Southport Speed Trials driving his 12 Hp Gladiator, shocking British society as she was the first woman, a working secretary, to compete in a 'motor race'.[15]

- ... "Selwyn Edge, Director of the Napier Car Company and famous racing driver ... spotted Miss Dorothy Levitt amongst his staff, a beautiful secretary with long legs and eyes like pools. In a bid to promote his cars ... Edge decided that she should take part in a race, though first he had to teach her to drive. She surpassed his expectations by winning her class in the 1903 Southport Speed Trial, and proved such a good driver that she was taken on by De Dion for a major publicity stunt." Jean Francois Bouzanquet[16]

In June 1907 Edge broke the 24-hour distance record, driving a 60 hp (44.7 kW) Napier six, at the newly opened Brooklands track, accompanied by riding-mechanic Joseph H Blackburn.(Born 17 December 1875 D 8 May 1919)[17] He covered 1,581 miles (2544 km), 1,310 yards at an average speed of 65.905 mph (106.06 km/h). This record stood for 18 years.[13] In 1910 Edge was awarded the Dewar Trophy for his drive in top gear in a 60 hp (45 kW) Napier on the route London-Edinburgh-London.[18]

In 1922 Edge returned to Brooklands in a Spyker setting a new "Double 12" world record covering 1,782 miles 1,066 yards (2,868 km 693 m) at an average speed of 74.27 mph (119.53 km/h) for the aggregate 24 hours.[19]

Edge lent Mrs Victor Bruce an AC Six car (PF6465) which she drove in the 1927 Monte Carlo Rally, travelling 1,700 miles (2,700km) in 72 hours without sleep, finishing sixth overall, and winning the Coupe des Dames, for the women's class.[20]

His final contribution to motor racing was the inauguration of the Campbell Circuit at Brooklands in 1937.[1]

Motor yachting

In 1903 Edge won the inaugural British International Harmsworth Trophy for speedboats held on the River Lee, Queenstown, Cork Harbour, Ireland, in a boat called Napier I. The 40-foot (12 m) steel-hulled, 'Napier' speedboat fitted with a 3-blade propeller, achieved 19.3 mph (31.1 km/h). It was driven by Dorothy Levitt, but as both owner and entrant "S.F.Edge" is engraved on the trophy as the winner. The third crew member, Campbell Muir, may also have taken the controls.[21]

In May 1905 The Rudder reported that :

- The first event of the season, the Monaco meeting, from 2 to 16 April, ... is without precedent [for quantity of entrants] in yachting history; beginning with an exhibition of all types of motor-boats, lasting four days, after which three days afloat were allowed for preparations, the races began on 9 April and continued for the following week.[21]

Edge, driving Napier II, won the 100 kilometres (62 mi) race for racers in the eight to 12 metres classes in 1 hour 5 minutes, he also finished second in Napier 1 as it was common practice to describe the owner and entrant as the driver, even if he did not take the wheel.[21]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wise, David B., "Edge: Progenitor of the six-cylinder engine", in Northey, Tom, ed. World of Automobiles (London: Orbis Publishing Ltd, 1974), Volume 5, p.589.

- ^ a b c d Thoms, David (2004), "Edge, Selwyn Francis (1868–1940)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 18 June 2015 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ "Selwyn Francis Edge". CyclingRanking.com. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Bordeaux - Paris 1891". CyclingRanking.com. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ a b Kelly's_Directory, 1911, Westmeston, West Sussex; The Manchester Guardian, 8 September 1921, p.5; The Manchester Guardian, 8 April 1922, p.9.

- ^ a b The Manchester Guardian, 13 February 1940, Obituary, Page 3.

- ^ Hull, Peter G. "Napier: The Stradivarius of the Road", in Northey (1974), Volume 13, p.1485.

- ^ The Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 29 August 1907, Page 9.

- ^ The Vintage Car 1919–1930, T.R. Nicholson, Batsford, 1966, Page 317.

- ^ See history of British Anzani company

- ^ The Manchester Guardian, 17 March 1927, Page 11.

- ^ Hull, Peter G. "Napier: The Stradivarius of the Road", in Northey (1974), Volume 13, p.1483.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hull, Peter G. "Napier: The Stradivarius of the Road", in Northey (1974), Volume 13, p.1486-7.

- ^ "Profile of the restored 1902 Napier that won the Gordon Bennet Trophy". Birthplace of Speed. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012.

- ^ Co-driver Solutions – Women in Motorsport

- ^ Fast Ladies: Female Racing Drivers 1888 to 1970 By Jean Francois Bouzanquet

- ^ The Mercury, Hobart, Tasmania, Monday 12 August 1907, Page 2.

- ^ Motor Sport, January 1952, p.21.

- ^ The Manchester Guardian, 21 July 1922, Page 7.

- ^ Bouzanquet, Jean-François (2009). Fast ladies : female racing drivers, 1888-1970. Dorchester: Veloce. ISBN 978-1-84584-225-3. OCLC 305172909.

- ^ a b c Hydroplane History – French Launches and Launch Engines of 1905 by W. P. Stephens. (Transcribed from The Rudder, May 1905, p. 283-287)

Books

- My motoring reminiscences, Selwyn Francis Edge, Foulis, 1934. For a review of this book see: The Manchester Guardian, 18 October 1934, Page 7.