Square–cube law

The square–cube law (or cube–square law) is a mathematical principle, applied in a variety of scientific fields, which describes the relationship between the volume and the surface area as a shape's size increases or decreases. It was first described in 1638 by Galileo Galilei in his Two New Sciences as the "...ratio of two volumes is greater than the ratio of their surfaces".[1]

This principle states that, as a shape grows in size, its volume grows faster than its surface area. When applied to the real world this principle has many implications which are important in fields ranging from mechanical engineering to biomechanics. It helps explain phenomena including why large mammals like elephants have a harder time cooling themselves than small ones like mice, and why building taller and taller skyscrapers is increasingly difficult.

Description

The square–cube law can be stated as follows:

When an object undergoes a proportional increase in size, its new surface area is proportional to the square of the multiplier and its new volume is proportional to the cube of the multiplier.

Represented mathematically:[2] where is the original surface area and is the new surface area. where is the original volume, is the new volume, is the original length and is the new length.

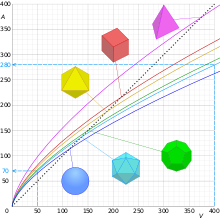

For example, a cube with a side length of 1 meter has a surface area of 6 m2 and a volume of 1 m3. If the dimensions of the cube were multiplied by 2, its surface area would be multiplied by the square of 2 and become 24 m2. Its volume would be multiplied by the cube of 2 and become 8 m3.

The original cube (1m sides) has a surface area to volume ratio of 6:1. The larger (2m sides) cube has a surface area to volume ratio of (24/8) 3:1. As the dimensions increase, the volume will continue to grow faster than the surface area. Thus the square–cube law. This principle applies to all solids.[3]

Applications

Engineering

When a physical object maintains the same density and is scaled up, its volume and mass are increased by the cube of the multiplier while its surface area increases only by the square of the same multiplier. This would mean that when the larger version of the object is accelerated at the same rate as the original, more pressure would be exerted on the surface of the larger object.

Consider a simple example of a body of mass, M, having an acceleration, a, and surface area, A, of the surface upon which the accelerating force is acting. The force due to acceleration, and the thrust pressure, .

Now, consider the object be exaggerated by a multiplier factor = x so that it has a new mass, , and the surface upon which the force is acting has a new surface area, .

The new force due to acceleration and the resulting thrust pressure,

Thus, just scaling up the size of an object, keeping the same material of construction (density), and same acceleration, would increase the thrust by the same scaling factor. This would indicate that the object would have less ability to resist stress and would be more prone to collapse while accelerating.

This is why large vehicles perform poorly in crash tests and why there are theorized limits as to how high buildings can be built. Similarly, the larger an object is, the less other objects would resist its motion, causing its deceleration.

Engineering examples

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

- Steam engine: James Watt, working as an instrument maker for the University of Glasgow, was given a scale model Newcomen steam engine to put in working order. Watt recognized the problem as being related to the square–cube law, in that the surface to volume ratio of the model's cylinder was greater than that of the much larger commercial engines, leading to excessive heat loss.[4] Experiments with this model led to Watt's famous improvements to the steam engine.

- Airbus A380: the lift and control surfaces (wings, rudders and elevators) are relatively big compared to the fuselage of the airplane. For example, taking a Boeing 737 and merely magnifying its dimensions to the size of an A380 would result in wings that are too small for the aircraft weight, because of the square–cube rule.

- Expander cycle rocket engines suffer from the square–cube law. Their size, and therefore thrust, is limited by heat transfer efficiency due to the surface area of the nozzle increasing slower than the volume of fuel flowing through the nozzle.

- A clipper needs relatively more sail surface than a sloop to reach the same speed, meaning there is a higher sail-surface-to-sail-surface ratio between these craft than there is a weight-to-weight ratio.

- Aerostats generally benefit from the square–cube law. As the radius () of a balloon is increased, the cost in surface area increases quadratically (), but the lift generated from volume increases cubically ().

- Structural Engineering: Materials that work at small scales may not work at larger scales. For example, the compressive stress at the bottom of small free-standing column scales at the same rate as the size of the column. Therefore, there exists a size for a given material and density at which a column will collapse on itself.

Biomechanics

If an animal were isometrically scaled up by a considerable amount, its relative muscular strength would be severely reduced, since the cross section of its muscles would increase by the square of the scaling factor while its mass would increase by the cube of the scaling factor. As a result of this, cardiovascular and respiratory functions would be severely burdened.

In the case of flying animals, the wing loading would be increased if they were isometrically scaled up, and they would therefore have to fly faster to gain the same amount of lift. Air resistance per unit mass is also higher for smaller animals (reducing terminal velocity) which is why a small animal like an ant cannot be seriously injured from impact with the ground after being dropped from any height.

As stated by J. B. S. Haldane, large animals do not look like small animals: an elephant cannot be mistaken for a mouse scaled up in size. This is due to allometric scaling: the bones of an elephant are necessarily proportionately much larger than the bones of a mouse, because they must carry proportionately higher weight. Haldane illustrates this in his seminal 1928 essay On Being the Right Size in referring to allegorical giants: "...consider a man 60 feet high...Giant Pope and Giant Pagan in the illustrated Pilgrim's Progress: ...These monsters...weighed 1000 times as much as [a normal human]. Every square inch of a giant bone had to support 10 times the weight borne by a square inch of human bone. As the average human thigh-bone breaks under about 10 times the human weight, Pope and Pagan would have broken their thighs every time they took a step."[5] Consequently, most animals show allometric scaling with increased size, both among species and within a species. The giant creatures seen in monster movies (e.g., Godzilla, King Kong, and Them!) are also unrealistic, given that their sheer size would force them to collapse.

However, the buoyancy of water negates to some extent the effects of gravity. Therefore, sea creatures can grow to very large sizes without the same musculoskeletal structures that would be required of similarly sized land creatures, and it is no coincidence that the largest animals to ever exist on earth are aquatic animals.

The metabolic rate of animals scales with a mathematical principle named quarter-power scaling[6] according to the metabolic theory of ecology.

Mass and heat transfer

Mass transfer, such as diffusion to smaller objects such as living cells is faster than diffusion to larger objects such as entire animals. Thus, in chemical processes that take place on a surface – rather than in the bulk – finer-divided material is more active. For example, the activity of a heterogeneous catalyst is higher when it is divided into finer particles. Such catalysts typically occur in warmer conditions.

Heat production from a chemical process scales with the cube of the linear dimension (height, width) of the vessel, but the vessel surface area scales with only the square of the linear dimension. Consequently, larger vessels are much more difficult to cool. Also, large-scale piping for transferring hot fluids is difficult to simulate in small scale, because heat is transferred faster out from smaller pipes. Failure to take this into account in process design may lead to catastrophic thermal runaway.

See also

- Biomechanics

- Allometric law

- On Being the Right Size, an essay by J. B. S. Haldane that considers the changes in shape of animals that would be required by a large change in size

- Surface-area-to-volume ratio

- Kleiber's law

- Bergmann's rule

References

- ^ David H. Allen (24 September 2013). How Mechanics Shaped the Modern World. ISBN 9783319017013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "World Builders: The Sizes of Living Things". world-builders.org. Archived from the original on 2016-10-23. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ^ Michael C. LaBarbera. "The Biology of B-Movie Monsters".

- ^ Rosen, William (2012). The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry and Invention. University of Chicago Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0226726342.

- ^ Haldane, J. B. S. "On Being the Right Size". Internet Research Lab. UCLA. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ George Johnson (January 12, 1999). "Of Mice and Elephants: A Matter of Scale". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-06-11.