Suasoria

Suasoria is an exercise in rhetoric: a form of declamation in which the student makes a speech which is the soliloquy of an historical figure debating how to proceed at a critical junction in their life.[1] As an academic exercise, the speech is delivered as if in court against an adversary and was based on the Roman rhetorical doctrine and practice.[2] The ancient Roman orator Quintilian said that suasoria may call upon a student to address an individual or groups such as the Senate, the citizens of Rome, Greeks or barbarians.[3] The role-playing exercise developed the student's imagination as well as their logical and rhetorical skills.[3]

Origin

The formal introduction of suasoria as a school form is unknown.[4] One of the earliest forms of this exercise, however, involved Cicero's practice of philosophical theses, which were addressed to the self.[4] The exercise became prevalent in ancient Rome, where it was, with the controversia, the final stage of a course in rhetoric at an academy. One famous instance was recalled by Juvenal in the first of his Satires:[5]

Et nos ergo manum ferulæ subduximus: et nos

Consilium dedimus Syllæ privatus ut altum

Dormiret. Stulta est clementia cum tot ubique

Vatibus occurras perituræ parcere chartæ.

I too have felt the master's cane upon my hand. I too

have given Sulla advice to retire into a deep

sleep. No point in sparing paper which is doomed to

destruction as you meet all those 'bards' everywhere.

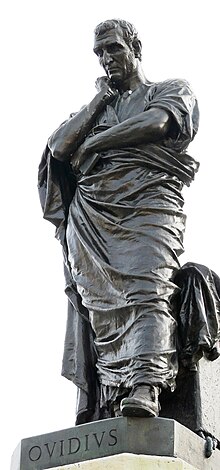

Here Juvenal recalls his speech advising the dictator Sulla to retire. Another Roman poet who recalled enjoying his suasoria was Ovid.[6]

Surviving examples

A book of suasoriae survive from antiquity, recorded in Suasoria by Seneca the Elder.[7] He writes responses and analysis of responses on seven suasoriae:

- Alexander debates whether to sail the ocean,[8]

- The three hundred Spartans sent against Xerxes deliberate whether they too should retreat following the flight of the contingents of three hundred sent from all over Greece,[9]

- Agamemnon deliberates whether to sacrifice Iphigenia for Calcas says otherwise sailing is impermissible,[10]

- Alexander the Great warned of danger by an augur deliberates whether to enter Babylon,[11]

- Xerxes has threatened to return unless the trophies of the Persian War are removed: the Athenians deliberate whether to do so,[12]

- Cicero deliberates whether to beg Antony’s pardon,[13] and

- Antony promises to spare Cicero's life if he burns his writings: Cicero deliberates whether to do so.[14]

References

- ^ Bloomer, W. Martin (2010), "Roman Declamation: The Elder Seneca and Quintilian", A Companion to Roman Rhetoric, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 301–302, ISBN 9781444334159

- ^ Evans, Ernest (2016). Tertullian's Treatise on the Incarnation: The Text Edited with an Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. x. ISBN 9781498297677.

- ^ a b Mendelson, M. (2013-06-29). Many Sides: A Protagorean Approach to the Theory, Practice and Pedagogy of Argument. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 258. ISBN 9789401598903.

- ^ a b Dominik, William; Hall, Jon (2010). A Companion to Roman Rhetoric. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell. p. 302. ISBN 9781405120913.

- ^ Susanna Morton Braund (1997), "Declamation and contestation in satire", Roman Eloquence: Rhetoric in Society and Literature, Routledge, p. 147, ISBN 9780415125444

- ^ "Education (Roman)", Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, vol. 9, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1912, p. 212

- ^ Gowing, Alain M. (2005-08-11). Empire and Memory. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511610592. ISBN 978-0-521-83622-7.

- ^ Seneca the Elder (1974). Suasoriae. Vol. 464. Harvard University Press. p. 485. doi:10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-suasoriae.1974.

- ^ Seneca the Elder (1974). Suasoriae. Vol. 464. Harvard University Press. p. 507. doi:10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-suasoriae.1974.

- ^ Seneca the Elder (1974). Suasoriae. Vol. 464. Harvard University Press. p. 535. doi:10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-suasoriae.1974.

- ^ Seneca the Elder (1974). Suasoriae. Vol. 464. Harvard University Press. p. 545. doi:10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-suasoriae.1974.

- ^ Seneca the Elder (1974). Suasoriae. Vol. 464. Harvard University Press. p. 551. doi:10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-suasoriae.1974.

- ^ Seneca the Elder (1974). Suasoriae. Vol. 464. Harvard University Press. p. 561. doi:10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-suasoriae.1974.

- ^ Seneca the Elder (1974). Suasoriae. Vol. 464. Harvard University Press. p. 595. doi:10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-suasoriae.1974.

External links

- Seneca, Suasoriae (translated by W.A. Edward) at attalus.org