Transverse abdominal muscle

| Transverse abdominal muscle | |

|---|---|

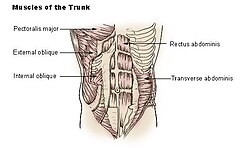

Muscles of the trunk. | |

| |

| Details | |

| Origin | Iliac crest, inguinal ligament, thoracolumbar fascia, and costal cartilages 7-12 |

| Insertion | Xiphoid process, linea alba, pubic crest and pecten pubis via conjoint tendon |

| Artery | subcostal arteries. |

| Nerve | Thoracoabdominal nn. (T6-T11), Subcostal n. (T12), iliohypogastric nerve (L1), and ilioinguinal nerve (L1). |

| Actions | Compresses abdominal contents |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Transversus abdominis |

| TA98 | A04.5.01.019 |

| TA2 | 2375 |

| FMA | 15570 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The transversus abdominis muscle, also known as the transverse abdominus, transversalis muscle and transverse abdominal muscle, is a muscle layer of the anterior and lateral abdominal wall which is deep to (layered below) the internal oblique muscle. It is thought to be a major muscle of the functional core of the human body, although some argue that due to its small cross-sectional area, it cannot generate the forces required to be a prime core stabilizer.

Structure

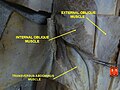

The transversus abdominis, so called for the direction of its fibers, is the innermost of the flat muscles of the abdomen, being placed immediately beneath the internal oblique muscle.

Origin

It arises, as fleshy fibers, from the lateral third of the inguinal ligament, from the anterior three-fourths of the inner lip of the iliac crest, from the inner surfaces of the cartilages of the lower six ribs, interdigitating with the diaphragm, and from the lumbodorsal fascia.

Insertion

The muscle ends anteriorly in a broad aponeurosis, the lower fibers of which curve inferomedially (medially and downward), and are inserted, together with those of the internal oblique muscle, into the crest of the pubis and pectineal line, forming the inguinal aponeurotic falx, also called the conjoint tendon. In layperson's terminology, the muscle ends in the middle line of a person's abdomen.

Throughout the rest of its extent the aponeurosis passes horizontally to the middle line, and is inserted into the linea alba; its upper three-fourths lie behind the rectus muscle and blend with the posterior lamella of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique; its lower fourth is in front of the rectus abdominis.

Layman's description

- The transverse abs run from our sides (lateral) to the front (anterior), its fibers running horizontally (transverse).

- The lateral beginnings of the muscle (origin) run from the front of the inside part of the hip bone [1] (anterior iliac crest and inguinal ligament) to the last rib of the rib cage. It also is connected to the diaphragm which helps with inhalation.

- The muscle runs transverse and is the deepest of the major abdominal muscles (the others being the rectus abdominis, and the internal and external obliques).

- It ends (the muscle insertion) by joining with the large vertical abdominal muscle in the middle (the linea alba), where the fibers begin to curve downward and upward depending on what direction it has to go to meet the linea alba, and below the sternum it combines with next most superficial muscle (the internal oblique). This insertion runs down by the belly button where it passes over the thick abdomen muscle (the "6/8-pack") and all the ab muscle fibers join together.

Innervation

The transversus abdominis is innervated by the lower intercostal nerves (thoracoabdominal, nerve root T7-T11), as well as the iliohypogastric nerve and the ilioinguinal nerve.

Actions

The transversus abdominis (TVA) helps to compress the ribs and viscera, providing thoracic and pelvic stability. This is explained further here. The transversus abdominis also helps pregnant women deliver their child.

Variations

It may be more or less fused with the Obliquus internus or absent. The spermatic cord may pierce its lower border. Slender muscle slips from the ileopectineal line to transversalis fascia, the aponeurosis of the Transversus abdominis or the outer end of the linea semicircularis and other slender slips are occasionally found. The nerves associated with the transverse abdominus are the intercostal, iliohypogastric, and the ilioinguinal.

Exercise

The most well known method of strengthening the TVA is the vacuum exercise. The TVA also (involuntarily) contracts during many lifts; it is the body's natural weight-lifting belt, stabilizing the spine and pelvis during lifting movements. It has been estimated that the contraction of the TVA and other muscles reduces the vertical pressure on the intervertebral discs by as much as 40%.[1] Failure to engage the TVA during higher intensity lifts is dangerous and encourages injury to the spine. The TVA acts as a girdle or corset by creating hoop tension around the midsection.

Without a stable spine, one aided by proper contraction of the TVA, the nervous system fails to recruit the muscles in the extremities efficiently, and functional movements cannot be properly performed.[2] The transversus abdominis and the segmental stabilizers (e.g. the multifidi) of the spine are designed to work in tandem.

While it is true that the TVA is vital to back and core health, the muscle also has the effect of pulling in what would otherwise be a protruding abdomen (hence its nickname, the “corset muscle”). Training the rectus abdominis muscles alone will not and can not give one a "flat" belly; this effect is achieved only through training the TVA.[3] Thus to the extent that traditional abdominal exercises (e.g. crunches) or more advanced abdominal exercises tend to "flatten" the belly, this is owed to the tangential training of the TVA inherent in such exercises. Recently the transversus abdominis has become the subject of debate between kinesiologists, strength trainers, and physical therapists. The two positions on the muscle are (1) that the muscle is effective and capable of bracing the human core during extremely heavy lifts and (2) that it is not.

Additional images

-

Diagram of a transverse section of the posterior abdominal wall, to show the disposition of the lumbodorsal fascia.

-

Posterior surface of sternum and costal cartilages, showing Transversus thoracis.

-

The interfoveolar ligament, seen from in front.

-

Diagram of sheath of Rectus.

-

Diagram of a transverse section through the anterior abdomina wall, below the linea semicircularis.

-

The abdominal inguinal ring.

-

The abdominal aorta and its branches.

-

Transversus abdominis muscle

External links

- . GPnotebook https://www.gpnotebook.co.uk/simplepage.cfm?ID=718274638.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Template:MuscleLoyola

- Anatomy figure: 35:07-04 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Incision and reflection of the internal abdominal oblique muscle."

- Anatomy photo:35:17-0100 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Anterior Abdominal Wall: The Transversus Abdominis Muscle"

- Anatomy figure: 40:07-06 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Muscles and nerves of the posterior abdominal wall."

- Anatomy image:7183 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy image:7194 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy image:7209 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy image:7311 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Exercising the Transversus Abdominis

- TVA vs. Weight Belt Debate

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 414 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 414 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

References

- ^ Hodges P.W., Richardson C.A., Contraction of the Abdominal Muscles Associated With Movement of the Lower Limb. Physical Therapy. Vol. 77 No. 2 February 1997.

- ^ Aruin S.A., Latash M.L. Directional specificity of postural muscles in feed-forward postural reactions during fast voluntary arm movements. Exp Brain Res (1995) 103:323-332.

- ^ Dart R.A. "The Double-Spiral Arrangement Of The Voluntary Musculature In The Human Body". Surgeons' Hall Journal Vol. 10, No. 2. March 1947.