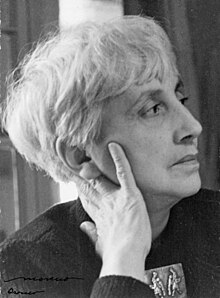

Winétt de Rokha

Winétt de Rokha was the mid-career pen name of the Chilean poet and writer Luisa Victoria Anabalón Sanderson (July 7, 1892 – August 7, 1951). Born to an upper-middle class Catholic family in Santiago, she published two books by her early twenties under another pseudonym, Juana Inés de la Cruz (the name of the seventeenth century Mexican poet and nun). In 1916, she met and eloped with the poet Pablo de Rokha (who was born Carlos Diaz Loyola). Together they invented her nom de plume. The De Rokha marriage produced nine children, seven of whom survived infancy. The De Rokha family, though touched several times by tragedy, became a famously accomplished Chilean clan.

From the late 1920s through the late 1940s, Winétt de Rokha published four collections of poetry upon which her literary reputation today largely rests: Formas del Sueño (1927), Cantoral (1936), Oniromancia (1943), and El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera (1949).

Biography

[edit]Winétt de Rokha, born Luisa Victoria Anabalón Sanderson, was the daughter of Indalecio Anabólon Urzúa, a general in the Chilean army, and Luisa Sanderson Mardones, a Santiago society lady. Biographical entries have usually listed Winétt's date of birth as 1892 but, according to a 2004 interview with Lukó de Rokha, her parents Pablo and Winétt were both born in the year 1894. Winétt's only brother, Carlos Anabalón Sanderson, was a judge who later became chief justice of Chile's Supreme Court.[1]

She credited her maternal grandfather, the classicist and scholar Domingo Sanderson, with introducing her as a young girl to literature and with first opening a door for her upon intellectual vistas beyond those of the Catholic faith.[2]

In 1939, Winétt and Pablo together founded the communist and anti-fascist literary journal and publishing house Multitud (whose slogan was "For bread, peace, and the liberty of the world").[3]

Chilean academic María Inés Zaldívar describes the tension between Winétt's origins and her life as poet, communist, and wife of Pablo de Rokha: "[She], in the personal as much in the public sphere, was a woman whose life and work, strongly interlaced, resists simple classifications. Her family background was very traditional, as she was born to an observant Catholic family in the upper ranks of Santiago society—a family that even had pretensions to nobility—but for the length of her life she committed herself instead to the pains and joys of a marriage of equals, to art as a form of life, and to ideologies that resolutely sought social justice and so clashed with the social milieu from which she came."[4]

Winétt de Rokha died in 1951 of cancer.

Critical reception

[edit]Winétt de Rokha may have been best known in her lifetime for poems of social protest, such as her lines written in solidarity with the Communists fighting Franco in Spain, or verses in praise of figures that included Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, and the children of the Soviet Union.[5]

Many of her poems in Formas del Sueño, Cantoral, and Oniromancia could be called surrealist, and have indeed been celebrated for the dream-like power of their images. The Chilean poet and visual artist Ludwig Zeller, in a 1945 review published in El Diario, characterized the poetry of Oniromancia as "verse carved into the root of the unconscious, overborne by swells of symbol and myth, full of tenderness and a pleasing melancholy toward everything that is past." Zeller also singled out for praise De Rokha's "indisputable pictorial sense."[6]

The poems in the three books mentioned above are all free verse. Most are short lyrics. Longer poems from these books include "Forms of Dream" ("Formas del Sueño"), "Language without Words" ("Lenguaje sin Palabras"), and "Chain of Verbs" ("Cadena de Verbos").

Winétt de Rokha's poetic reputation fell into obscurity in the decades following the publication of a posthumous collected volume of her work, Suma y Destino, in 1951.

The editors of a recent selected edition and a recent critical collected edition of Winétt de Rokha's poetry both note that her own literary accomplishments were unfortunately overshadowed by her partnership with a man widely considered to be one of the great Chilean poets of the twentieth century. As the critic Javier Bello writes, "her books, her poems, her ideas, seem not to have been taken seriously beyond their place next to Pablo, next to the cultural network woven by the De Rokha marriage and everyone surrounding the couple."[7]

Bello considers the cryptic and difficult prose poems of El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera to be De Rokha's most innovative contribution to Latin American poetry.[8]

Published works and recent editions

[edit]Fotografía en oscuro: Selección poética. Ed. María Inés Zaldívar. Madrid: Colección Torremozas, 2008.

Winétt de Rokha: El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera, Edición Crítica de la Obra Poética. Ed. Javier Bello. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2008.

Oniromancia. Segunda Edición. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Multitud, 2011.

The Valley Loses Its Atmosphere / El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera. Trans. Jessica Sequeira. Shearsman Books, 2021.

External links

[edit]Pages devoted to Winétt de Rokha at the website of the Departamento de Literatura, Universidad de Chile:

- http://www.winett.uchile.cl/ (Spanish texts of poems, critical commentaries, photographs).

Three poems -- "Domingo Sanderson," "Otoňo en 1930," and "Escenario de Melopea en Antiguo"—in English translation at The Fortnightly Review:

References

[edit]- ^ Inés Zaldívar, María, ed. (2008). Fotografía en oscuro: Selección poética. Madrid: Colección Torremozas. pp. 10, 28. ISBN 978-84-7839-408-1.

- ^ Bello, Javier, ed. (2008). Winétt de Rokha: El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera, Edición Crítica de la Obra Poética. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio. p. 30. ISBN 978-956-260-439-0.

- ^ Inés Zaldívar, María, ed. (2008). Fotografía en oscuro: Selección poética. Madrid: Colección Torremozas. p. 17. ISBN 978-84-7839-408-1.

- ^ Inés Zaldívar, María, ed. (2008). Fotografía en oscuro: Selección poética. Madrid: Colección Torremozas. p. 5. ISBN 978-84-7839-408-1.

- ^ Nómez, Naín, ed. (2000). Antología crítica de la poesía chilena. Vol. Tomo II. Santiago, Chile: LOM Ediciones.

- ^ Bello, Javier, ed. (2008). Winétt de Rokha: El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera, Edición Crítica de la Obra Poética. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio. p. 425. ISBN 978-956-260-439-0.

- ^ Bello, Javier, ed. (2008). Winétt de Rokha: El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera, Edición Crítica de la Obra Poética. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-956-260-439-0.

- ^ Bello, Javier, ed. (2008). Winétt de Rokha: El Valle Pierde Su Atmósfera, Edición Crítica de la Obra Poética. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-956-260-439-0.