Xu Shen

Xu Shen | |

|---|---|

| 許慎 | |

| |

| Born | 58 CE Henan, China |

| Died | 148 CE (aged 89 or 90) |

| Occupation(s) | Calligrapher, philologist, politician, writer |

| Notable work | Shuowen Jiezi |

| Xu Shen | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 許慎 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 许慎 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Xu Shen (c. 58 – c. 148 CE) was a Chinese calligrapher, philologist, politician, and writer of the Eastern Han dynasty (25–189 CE).[1] During his own lifetime, Xu was recognized as a preeminent scholar of the Five Classics.[2] He was the author of Shuowen Jiezi,[3][4] which was the first comprehensive dictionary of Chinese characters, as well as the first to organize entries by radical.[2] This work continues to provide scholars with information on the development and historical usage of Chinese characters.[2] Xu Shen completed his first draft in 100 CE but, waited until 121 CE before having his son present the work to the Emperor An of Han.[5]

Life

[edit]Xu was born about 58 CE in the Zhaoling district of Run'an prefecture (modern Luohe in Henan).[1] He was a student of the scholar-official Jia Kui 賈逵 (30–101 CE).[6] Under Jia, he established himself as a master in his own right and enjoyed a positive reputation.[2] This education allowed him to hold several government offices at the prefecture level, and ultimately rise to a post in the royal library.[1][5] Before undertaking the Shuowen, he was already a prolific writer. Although lost, one of his better known early works was a commentary on the Huainanzi, an important sociopolitical work from the second century BCE.[1]

Xu Shen's life and work were shaped by the fierce division between Old Text and New Text schools of Confucian thought.[6] These rival camps grew out of the wide proliferation of Confucian texts, which was brought on by the Emperor Wu of Han's elevation Confucianism to the state philosophy.[6] Because knowledge of the Confucian canon was the primary qualification for government office, there was a large upswing in the rate of copying. These new additions were written in a standardized Han dynasty script.[6] During the reign of Emperor Cheng of Han (r. 33 – 7 BCE), however, older manuscripts were discovered in the imperial archives and in the walls of Confucius's family mansion.[6] These older texts were written in a pre-Qin, small seal script (xiaozhuan 小篆). Importantly, they also differed in their content and organization.[2] A group of scholars, which came to be called the Old Text school, emerged and advocated for the use of this more ancient version. The New Text school meanwhile preferred the more recent versions. Since Han jurisprudence was based on the classics, the interpretation of even a single character could lead to concrete differences in legal opinions.[7][2] The great variation in interpretations greatly troubled Xu.[1] He was familiar with both schools: Jia Kui was a respected Old Text scholar, but Xu's official work required familiarity with the New Text editions.[1][6] In an attempt to eliminate discrepancies between interpretations, Xu authored Different Meanings of the Five Classics (五經異義), a commentary, now lost, that incorporated interpretations from both the New and Old Text schools.[1] Xu picked the readings that were best to his mind, regardless of school.[1] Ultimately though, Xu decided that only a rigorous work on the development and history of each character could standardize the interpretation of the classics.

The Shuowen Jiezi

[edit]

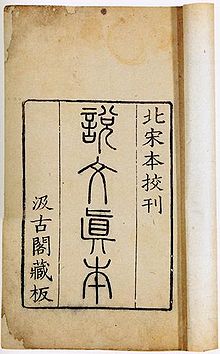

Xu Shen's desire to create an exhaustive reference work resulted in the Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字). The Shuowen has no standard English translation, and is sometimes rendered: "Explain the Graphs and Unravel the Written Words" or "Explaining Graphs and Analyzing Characters."[1] The uniting principle behind each part of the massive project was, as Xu Shen writes in his postface, "to establish defined categories, [to] correct mistaken concepts, for the benefit of scholars and true interpretation of the spirit of language."[5] Intended to be a comprehensive work, it encompasses 15 chapters and over 9,000 small seal script entries, and has a preface and a postface.[5][2] Xu intentionally listed headwords in pre-Qin characters in order to provide their earliest possible forms, and thereby allow the most faithful interpretation. It is among the first character dictionaries which examined the evolution of characters in detail, and streamlined the "six category" approach to analyzing Chinese writing.[7] It also created a system of 540 semantically organized radicals.[1]

Linguistic theory

[edit]In the postface, Xu gives a brief account of the history of writing. According to legend, Chinese characters were first invented by Cangjie, who was inspired by footprints to create a system of signs that refer to the natural world.[7] These original graphs could then be combined to make meaningful characters with referents distinct from their component graphs.[8] This was important for Xu Shen, who emphasized the productivity, even fertility, of Chinese writing.[8] Despite the novel meanings of compound characters, Xu Shen believed that true understanding of composite characters was contingent on an understanding of their components.[2] Providing clear explanation of these relationships lay at the heart of his motivation.[1]

Central to Xu Shen's thought is the contrast between wen (文 patterns) and zi (字 characters), indeed these contrasting categories of graphs receive separate mention in the work's title. Even today, there is disagreement over the exact definitions of the two terms. The Song dynasty scholar Zheng Qiao (鄭樵) first presented the interpretation that wen and zi are the difference between non-compound and compound characters.[7] More recently, other scholars, such as Françoise Bottéro (2002), have argued that the addition of a specifically phonetic element (and thus not simply compounding) marks the principal difference between wen and zi.[8] From this original binary contrast, Xu Shen formally delineated for the first time the six categories (六書) of Chinese characters.

- Indicators of Function (指事), whose forms are iconic without being based on concrete objects. Examples include 上 (shàng) and 下 (xià), indicating up and down respectively.[7]

- Form Imaging or Pictographs (象形), such as 山 (shān), meaning mountain.[7]

- Form and Sound (形聲), which consist of a semantic element and an element indicating pronunciation.[7] The character 汗 (hàn sweat), for example. contains the phonetic marker 干 (gān shield), and the semantic marker 氵(shuĭ water).

- Combining Meaning (會意), which unite two semantic elements. 明, for example contains the sun and the moon, and carries the meaning 'bright'.[7]

- Reciprocally Glossing (轉註), which arose from a divergence of one character into two separate characters still linked in sound and meaning, such as 老 (lăo) and 考 (kǎo).[7]

- Loaning Characters (假借鑑), which essentially indicates one character whose meaning has been broadened to contain multiple definitions. This is seen in bifurcated meanings and pronunciations of 長, which originally meant 'leader' (zhăng), but came to have the second meaning 'long' (cháng).[7]

To organize the thousands of headwords, Xu Shen established 540 radicals, and ordered them from least to greatest complexity. Each radical then headed its own group, which in turn subsumed all composite characters which incorporated the specific radical. The total number of 540 has a cosmological weight, as it can be derived from the product of 6, 9, and 10. 6 and 9 are the numbers of Yin and Yang, and 10 a number signifying completion. This number symbolizes the exhaustive scope of the dictionary.

Within the dictionary itself, each entry first gives the character's meaning, and alternate orthographies. It also accounts for a character's meaning, occasionally pronunciation, and cites examples of its use in the classical texts.

Models and influences

[edit]Xu Shen had to rely on a large body of sources to collect the thousands of characters and variants that appear in the Shuowen. Many small script characters were taken from the Cangjiepian (c. 220 BCE); ancient characters were collected from the texts found in Confucius's mansion, and Zhou characters were taken from the Historian Zhou's Primer (c. 578 BCE, the reign of King Xuan).[2]

The Shuowen has often been the subject of commentary and study. The earliest reported research was conducted in the Sui dynasty by Yu Yanmo (庾儼默), though this work has not survived. Later in the Tang dynasty (618–907), Li Yangbing (713–741) prepared an edition, though this version is lost as well.[2] The oldest surviving editions go back to a pair of brothers, Xu Xuan (徐鉉) and Xu Kai (徐鍇). The pair lived in the Sui dynasty (581–618), and their work ensured the long-term survival of the Shuowen.[2] The well-known philologist Duan Yucai (段玉裁 1735–1815) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) dedicated his life to studying the Shuowen, and produced the authoritative version and commentary still used today, the Shuowen Jiezi Zhu 說文解字註 (the Annotated Shuowen Jiezi).[2]

Xu Shen's work also provides a valuable resource for linguistic research. Duan Yucai based much of his research on the Shuowen, and the philologist Zhu Junsheng's (朱駿聲) phonological study Explanatory Book of Sounds 說文訓定生 was written as a companion to the Shuowen.[2]

Given the number of dictionaries and philological works that draw heavily from the Shuowen, Xu Shen has towered over the field of Chinese lexicography, and his influence is still felt today.[2]

Criticism

[edit]A number of Xu Shen's character analyses are erroneous, as the seal script differs considerably from the older bronzeware script and the even older oracle bone script, both of which were unknown at the time, also to Xu Shen. Karlgren, for example, disputes Xu Shen's interpretation of 巠 (jing) as depicting a subterranean water channel. Referring to the bronze script, he proposes a reading linked to weaving.[9] Furthermore, Xu Shen does not account for historical phonological change between the earliest days of Chinese writing and his own era. This results in inaccurate sound analyses.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brown, Kerry, ed. (2014). Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography. Berkshire Publishing. ISBN 9781933782669.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Yong, Heming; Peng, Jing (2008). Chinese Lexicography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199539826.

- ^ Daijisen entry "Xu Shen" (Kyo Shin in Japanese). Shogakukan.

- ^ Kanjigen entry "Xu Shen" (Kyo Shin in Japanese). Gakken, 2006.

- ^ a b c d Xu, Guozhang (1990). "Language and society as seen by Xu Shen, an ancient Chinese lexicographer". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 1990 (81): 51–62. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1990.81.51. S2CID 146757568.

- ^ a b c d e f Yuan, Xingpei, ed. (2012). The History of Chinese Civilization. Vol. 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01306-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lewis, Mark Edwards (1999). Writing and Authority in Early China. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791441148.

- ^ a b c Bottéro, Françoise (2002). "Revisiting the wén 文 and the zì 字: The Great Chinese Character Hoax". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 74: 14–33.

- ^ Karlgren, Bernhard (1957). Grammata Serica Recensa. Stockholm: Museum of Far Easter Antiquities. p. 219.

- ^ Mair, Victor, ed. (2001). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 46-46. ISBN 0231109849.

Cited works

[edit]- Mair, Victor H. (ed.) (2001). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10984-9. (Amazon Kindle edition.)

Further reading

[edit]- He Jiuying 何九盈 (1995). Zhongguo gudai yuyanxue shi (中囯古代语言学史 "A history of ancient Chinese linguistics"). Guangzhou: Guangdong jiaoyu chubanshe.