Russification of Belarus

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Belarusian (Taraškievica orthography). (November 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

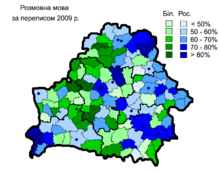

The Russification of Belarus (Belarusian: Русіфікацыя Беларусі, romanized: Rusifikatsyya Byelarusi; Russian: Русификация Беларуси, romanized: Rusifikatsiya Belarusi) denotes a historical process where the integration of Russian language and culture increasingly influenced Belarusian society, especially during the 20th century.[1]

This period witnessed a notable rise in the use of the Russian language in education, administration, and public life, often paralleling and sometimes overshadowing the Belarusian cultural and linguistic elements.

Evolution of Russification Policies in Belarus[edit]

Russian Empire[edit]

According to the terminology of the 18th and 19th centuries, Russification meant the strengthening of the local culture of all three branches of the Pan-Russian people, with Russian language considered the main literary standard, while Belarusian language was regarded as its dialect, in which literature was also published.[2][3]

The active introduction of Russian language in education and administration, part of the Empire's modernization efforts, provided Belarusians with enhanced access to education and broader cultural engagement.[4] This period also saw the growth of a distinct Belarusian national consciousness, influenced by the socio-economic changes and cultural exchanges within the Empire.[5]

Study of the Belarusian Language in the Russian Empire[edit]

Interest in studying the language of the local population began to emerge in the academic community in the late 19th century. Izmail Sreznevsky and Alexander Potebnja considered Belarusian dialects to be part of the South Russian vernacular.[6] Most researchers were quite skeptical at the time about the prospects of socializing the Belarusian language. As noted by the famous ethnographer and collector of Belarusian folklore, Pyotr Bessonov: "The Belarusian oral folk speech will never become a literary, written, and book language".[7]

The first scholar to thoroughly approach the study of Belarusian dialects was Yefim Karsky, considered the founder of Belarusian linguistics. Based on his many years of research, he published a three-volume work "The Belarusians" in 1903-1922, with the first volume containing his "Ethnographic Map of the Belarusian Tribe. Belarusian Dialects".[8]

Soviet Era[edit]

In Belarus, the initial phase of Russification was undertaken by the authorities of the Russian Empire, which was later followed by a period of cultural promotion and national development under the Soviet policy of belarusization.[9] This phase, however, eventually gave way to a renewed emphasis on Russification under subsequent Soviet policies.[10][11][12][13]

Candidate of Philological Sciences Igor Klimov writes:

The Bolshevik state, in its unique historical experiment of creating a new society and a new human being, viewed language as an object of special manipulation aimed at achieving certain non-linguistic goals. A key aspect of these manipulations, starting from 1930, was to reinforce Russian influence in the literary language norms of other ethnicities of the USSR. This enhanced cultural homogeneity among the peoples of the Soviet empire, subdued their separatist aspirations, and facilitated their cultural and linguistic assimilation. From the 1930s, the Belarusian language became a victim of this policy, its further development being influenced not by internal necessity or actual usage, but by the internal dynamics of the Soviet state.[14]

In 1958, a school reform was implemented, granting parents the right to choose the language of instruction and determine whether their children should learn the national language. As a result, the number of national schools and their student populations sharply declined.[15][16] For instance, in 1969 in the Byelorussian SSR, 30% of students did not study the Belarusian language, and in Minsk, the figure was 90%. Researchers attribute this phenomenon to parents preferring to educate their children in a language that would facilitate further education in Russian-speaking secondary specialized and higher education institutions, both within Belarus and abroad, ultimately laying the groundwork for a successful career. As Vladimir Alpatov notes:

This led to a paradoxical situation at first glance: many national schools were more supported from above, sometimes out of inertia, while there was a movement from below towards switching to education in Russian (not excluding the study of the mother tongue as a subject).[17]

Presidency of Alexander Lukashenko[edit]

Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko has renewed the policy since coming to power in 1994,[18][19][20][21][22] although with signs of a "soft Belarusization" (Belarusian: мяккая беларусізацыя, romanized: miakkaja biełarusizacyja) after 2014.[23][24][25]

In Minsk city for the 1994-1995 academic year, 58% of students in the first classes of elementary school were taught in the Belarusian language. After the beginning of Lukashenko's presidency in 1994, the number of these classes decreased. In 1999, only 5.3% of students in the first classes of elementary school were taught in the Belarusian language in Minsk.[26]

In the academic year 2016-2017 near 128,000 students were taught in Belarusian language (13.3% of total).[27] The vast majority of Belarusian-language schools located in rural areas that are gradually closed through the exodus of its population to the cities. Each year, there is a closure of about 100 small schools in Belarus, most of which use Belarusian language in teaching. There is a trend of transfer the students of these schools to Russian-language schools. Thus, there is a loss of students studying in Belarusian.[28]

As for the cities, there are only seven Belarusian-language schools, six of which are in Minsk (in 2019). In other words, the capital city, regional and district centers of the Republic of Belarus has seven Belarusian-language schools in total:

- Gymnasium № 4 (Kuntsaushchyna street, 18 – Minsk, Frunzyenski District)

- Gymnasium № 9 (Siadykh street, 10 – Minsk, Pyershamayski District)

- Gymnasium № 14 (Vasnyatsova street, 10 – Minsk, Zavodski District)

- Gymnasium № 23 (Nezalezhnastsi Avenue, 45 – Minsk, Savyetski District)

- Gymnasium № 28 (Rakasouski Avenue, 93 – Minsk, Leninsky District)

- Secondary school № 60 (Karl Libkneht street, 82 – Minsk, Maskowski District)

- Secondary school № 4 (Savetskaya street, 78 – Ivanava city)

| Settlement | Number of Belarusian-language schools | Total number of schools | Percentage of Belarusian-language schools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minsk | 6 | 277 | 2.17% |

| Brest | 0 | 37 | 0% |

| Vitsebsk | 0 | 48 | 0% |

| Hrodna | 0 | 42 | 0% |

| Homel | 0 | 53 | 0% |

| Mahilyow | 0 | 47 | 0% |

| District centers in total (except the capital and regional centers) |

1* | ~ 920 | 0.11% |

| * in Ivanava (secondary school № 4)[29] | |||

Current State of Belarusian Language[edit]

The Belarusian language, while recognized as the national language, is less utilized in everyday communication compared to Russian, and is not prestigious as a language of education and professional growth.[30] Despite its limited use in public life, Belarusian has a rich literary tradition and cultural presence, embodied by literary masterpieces from renowned authors like Vasil Bykaŭ and Uladzimir Karatkievich.[30] Efforts continue to revive and promote the Belarusian language through various media including the historically significant newspaper "Nasha Niva" and modern internet platforms.[30]

Components of Russification[edit]

The Russification of Belarus comprises several components:

- Russification of education

- Domination of the Russian language within education in Belarus[19]

- Repressions of Belarusian elites standing on the positions of national independence and building a Belarusian state on the basis of Belarusian national attributes

- Codification of the Belarusian language to bring it closer to Russian[13]

- Declaring Russian as the second official language, creating conditions for crowding out the Belarusian language[13]

- Destruction or modification of national architecture[31][32]

- Renaming of settlements, streets and other geographical objects in honor of Russian figures or according to Russian tradition[33][34]

- The dominance of Russian television and Russian products in the media space of Belarus[19]

- Lack of conditions for the use of the Belarusian language in business and documents workflow[19]

- Religious suppression and forced conversion

Chronology[edit]

- 1764. Catherine's II instruction on the Russification of Ukraine, Smolensk (ethnic Belarusian territory), Lithuania and Finland [35].

- 1772. After the first partition of Poland, part of the ethnic Belarusian lands became part of the Russian Empire [36]. Catherine II signed a decree according to which all governors of the annexed territories had to write their sentences, decrees and orders only in Russian. The enslavement of the local people also began: about half a million previously free Belarusians became the property of Russian nobles [37].

- 1773. Catherine II signed another order "On the establishment of local courts", which once again provided for the mandatory use of exclusively Russian language in archives [38].

- 1787. Catherine II decreed that religious books could be printed in the Russian Empire only in publishing houses subordinate to the Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, as a result of which Greek-Catholic printing houses were banned [39].

- 1794. Kościuszko Uprising is crushed by Alexander Suvorov's troops, he receives 25,000 Belarusian serfs as a reward [40]

- 1795. Russia officially denies the existence of the Belarusian nation and a separate Belarusian language. Mass arrests of local Belarusian politicians and their replacement by Russian ones began [41]

- 1831. After Emperor Nicholas I came to power, the November Uprising was suppressed. The Minister of Internal Affairs of Russia, Pyotr Valuyev, prepared a "Special Essay on Means of Russification of the Western Territory" (Russian. Очерк о средствах обрусения Западного края) [42])

- 1832. Mass liquidation of Greek Catholic and Basilian schools, which favored the Belarusian language and culture, was carried out. Strengthening control over education by the Russian Orthodox Church [43]

- 1840. Nicholas I issued a decree according to which it was forbidden to use the words "Belarus" (Беларусь) and "Belarusians" (беларусы) in official documents. In the official documentation, the country received the name Northwestern territory [44] [45] [46]

- 1852. With the liquidation of the Greek Catholic Church, the mass destruction of Belarusian religious literature began. Joseph Semashko was a personal witness of the burning of 1,295 books found in Belarusian churches. In his memoirs, he proudly reports that over the next three years, two thousand volumes of books in the Belarusian language were burned by his order [47] · [48].

- 1864. Mikhail Muravyov-Vilensky known for his abuse of the Belarusian people, became the governor-general of the "North-Western Territory" [49]. He paid special attention to education, Muravyov's motto became famous: "What the Russian bayonet didnt finish, the Russian school and church will finish" (Russian. Что не доделал русский штык - доделает русская школа и церковь) [50] [51] [45] [52].

- 1900. the Ministry of Education of Russia set the following task for all schools: "children of different nationalities receive a purely Russian orientation and prepare for complete fusion with the Russian nation" [53]

- 1914. Belarusian people werent mentioned in the resolutions of the First Russian Congress of Peoples Education. In general, during the entire period of rule in Belarus, the Russian goverment didnt allow the opening of a single Belarusian school [54]

- 1929. the end of Belarusization, and beginning of mass political repressions [55] [56].

- 1930. In the USSR, under the guise of the "struggle against religion", the mass destruction of unique architectural monuments begins. By order of the Soviet authorities, the ancient monasteries of Vitebsk, Orsha, and Polotsk were destroyed [57] [58] [59]

- 1937. By order of the Soviet gpverment, all representatives of the then Belarusian intelligentsia were shot, and their remains were buried on the territory of the Kurapaty tract [60]

- 1942. Yanka Kupala, a classic of Belarusian literature, was assassinated by Soviet secret services while in Moscow

- 1948. Alesya Furs, an activist of the national liberation movement, was sentenced to 25 years in prison for displaying the Belarusian coat of arms Pahonia [61]

- 1960. After the World War II, under the guise of general plans for the restoration and reconstruction of cities, the destruction of architectural monuments continues. Belarusians experienced the greatest losses in terms of architectural heritage in the 1960s and 1970s [62]

- 1995. After Alexander Lukashenko came to power, the state symbols of Belarus - the white-red-white flag and the historic coat of arms of Pahonia were replaced with modified Soviet symbols, and the national anthem was also replaced. In addition, the Russian language received the status of the second state language (the Russian language is used in all educational institutions and in the mass media), according to UNESCO, the Belarusian language is in danger of disappearing [63].

See also[edit]

- Russification

- Belarusization

- Belarusian national revival

- Belarusian nationalism

- Trasianka

- Polonization

- Russification of Ukraine

References[edit]

- ^ "О русском языке в Белоруссии". pp. 23–24. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "Белорусский: история, сходство языками Европы и трудности перевода". Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "О русском языке в Белоруссии". p. 23. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Трещенок, Я. И. (2003). История Беларуси. Досоветский период часть 1 (in Russian). pp. 124–125.

- ^ Трещенок, Я. И. (2003). История Беларуси. Досоветский период часть 1 (in Russian). pp. 135–138.

- ^ Крывіцкі, А. А. (1994). Асноўны масіў беларускіх гаворак (in Belarusian). Мінск. p. 55.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Коряков, Ю. Б. Языковая ситуация в Белоруссии и типология языковых ситуаций (in Russian). p. 28.

- ^ Коряков, Ю. Б. Языковая ситуация в Белоруссии и типология языковых ситуаций (in Russian). p. 26.

- ^ Marková, Alena (2021). "Conclusion. A Theoretical Framework for Belarusization". The Path to a Soviet Nation. pp. 245–261. doi:10.30965/9783657791811_010. ISBN 978-3-657-79181-1. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Early Belorussian Nationalism in [Helen Fedor, ed. Belarus: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995.]

- ^ Stalin and Russification in [Helen Fedor, ed. Belarus: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995.]

- ^ Why Belarusians Don’t Speak Their Native Language? // BelarusFeed

- ^ a b c Yuliya Brel. (University of Delaware) The Failure of the Language Policy in Belarus. New Visions for Public Affairs, Volume 9, Spring 2017, pp. 59—74

- ^ Клімаў, І. (2004). "Мова і соцыўм (Terra Alba III)". Два стандарты беларускай літаратурнай мовы (in Belarusian). Магілёў.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Алпатов, В. (1997). 150 языков и политика: 1917—1997. Социолингвистические проблемы СССР и постсоветского пространства [150 Languages and Politics: 1917–1997. Sociolinguistic Issues of the USSR and Post-Soviet Space] (in Russian). М., Ин-т востоковедения. p. 99.

- ^ Мікуліч, Т. (1996). Мова і этнічная самасвядомасць [Language and Ethnic Self-Awareness] (in Belarusian). pp. 95–96.

- ^ Алпатов, В. 150 языков и политика: 1917—1997. Социолингвистические проблемы СССР и постсоветского пространства [150 Languages and Politics: 1917–1997. Sociolinguistic Issues of the USSR and Post-Soviet Space] (in Russian). p. 100.

- ^ Belarus has an identity crisis // openDemocracy

- ^ a b c d Vadzim Smok. Belarusian Identity: the Impact of Lukashenka’s Rule // Analytical Paper. Ostrogorski Centre, BelarusDigest, December 9, 2013

- ^ Нацыянальная катастрофа на тле мяккай беларусізацыі // Novy Chas (in Belarusian)

- ^ Галоўная бяда беларусаў у Беларусі — мова // Novy Chas (in Belarusian)

- ^ Аляксандар Русіфікатар // Nasha Niva (in Belarusian)

- ^ "Belarus leader switches to state language from Russian", BBC, July 10, 2014

- ^ "Belarus in the multipolar world: Lukashenka bets on himself". New Eastern Europe - A bimonthly news magazine dedicated to Central and Eastern European affairs. January 21, 2020.

- ^ Ivan Prosokhin, "Soft Belarusization: (Re)building of Identity or “Border Reinforcement”?" doi:10.11649/ch.2019.005

- ^ Антонава Т. Моўныя пытаньні ў Беларусі // Зьвязда, 10 красавіка 1999 №59 (23660), 4–5 pp. (in Belarusian)

- ^ Марціновіч Я. Моўная катастрофа: за 10 гадоў колькасць беларускамоўных школьнікаў скарацілася ўдвая // Nasha Niva, May 31, 2017 (in Belarusian)

- ^ Алег Трусаў: Скарачэнне беларускамоўных школ можа прывесці да выраджэння нацыі Archived September 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine // Берасьцейская вясна (in Belarusian)

- ^ Вучыцца на роднай мове. 8 фактаў пра беларускія школы // Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Belarusian)

- ^ a b c Гринберг, С. А. ВЛИЯНИЕ БЕЛОРУССКО-РУССКОГО ДВУЯЗЫЧИЯ НА МИРОВОЗЗРЕНИЕ И НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЕ САМОСОЗНАНИЕ БЕЛОРУСОВ [INFLUENCE OF THE BILINGUALISM ON OUTLOOK AND NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS OF BELARUSIANS] (in Russian). Витебский государственный университет им. П.М. Машерова. p. 3.

- ^ Страчаная спадчына. — Менск, 2003. С. 54. (in Belarusian)

- ^ Волкава В. Мінск 21 лютага 1918 г. вачыма нямецкага салдата (па матэрыялах газеты "Zeitung der 10. Armee") // Беларускі гістарычны часопіс. № 2, 2018. С. 11. (in Belarusian)

- ^ Соркіна І. Палітыка царызму адносна гарадоў Беларусі ў кантэксце гістарычнай памяці і ідэнтычнасці гараджанаў // Трэці міжнародны кангрэс даследчыкаў Беларусі. Працоўныя матэрыялы. Том 3. 2014. С. 376. (in Belarusian)

- ^ Kapylou I., Lipnitskaya S. Current status and related problems of national toponyms standardization in the Republic of Belarus // Studia Białorutenistyczne. Nr. 8, 2014.

- ^ Собственноручное наставление Екатерины II князю Вяземскому при вступлении им в должность генерал-прокурора (1764 года)

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Краіна Беларусь. Вялікае Княства Літоўскае (2012) С. 330.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Гістарычны шлях беларускай нацыі і дзяржавы С. 39.

- ^ Дакументы і матэрыялы па гісторыі Беларусі. Т. 2. — Менск, 1940.

- ^ Філатава А. Нацыянальнае пытанне і палітыка царскага ўраду ў Беларусі (канец XVIII — першая палова ХIХ ст.) // Беларускі Гістарычны Агляд. Т. 7, Сш. 1, 2000.

- ^ Швед В. Эвалюцыя расейскай урадавай палітыкі адносна земляў Беларусі (1772—1863 г.) // Гістарычны Альманах. Том 7, 2002.

- ^ Крыжаноўскі М. Жывая крыніца ты, родная мова // Народная Воля. № 65—66, 1 траўня 2008 г.

- ^ Миллер А. И. Планы властей по усилению русского ассимиляторского потенциала в Западном крае // «Украинский вопрос» в политике властей и русском общественном мнении (вторая половина XIХ века). — СПб: Алетейя, 2000.

- ^ Арлоў У. Як беларусы змагаліся супраць расейскага панавання? // Template:Літаратура/100 пытаньняў і адказаў з гісторыі Беларусі С. 51—52.

- ^ Арлоў У. Дзесяць вякоў беларускай гісторыі (862―1918): Падзеі. Даты. Ілюстрацыі. / У. Арлоў, Г. Сагановіч. ― Вільня: «Наша Будучыня», 1999.

- ^ a b Template:Літаратура/Гісторыя Беларусі (у кантэксьце сусьветных цывілізацыяў) С. 237.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Гісторыя Беларусі (у кантэксьце сусьветных цывілізацыяў) С. 228.

- ^ Калубовіч А. Мова ў гісторыі беларускага пісьменства. Клыўлэнд, 1978. [1]

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Дзесяць вякоў беларускай гісторыі (1997)

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Гісторыя Беларусі (у кантэксьце сусьветных цывілізацыяў) С. 257.

- ^ У менскім праваслаўным храме маліліся за Мураўёва-вешальніка — упершыню за сто гадоў, Радыё Свабода, 23 лістапада 2016 г.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Гістарыяграфія гісторыі Беларусі С. 133.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Гісторыя Беларусі (у кантэксьце сусьветных цывілізацыяў) С. 291.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Краіна Беларусь. Вялікае Княства Літоўскае (2012) С. 327.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Русіфікацыя: царская, савецкая, прэзыдэнцкая (2010) С. 19.

- ^ Катлярчук А. Прадмова да «літоўскага» нумару // Arche № 9, 2009.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Даведнік Маракова

- ^ Пацюпа Ю. Занядбаная старонка правапісу: прапановы пісаньня прыназоўніка у/ў перад словамі, што пачынаюцца з галоснай // Arche. № 6 (29), 2003.

- ^ Бекус Н. Тэрапія альтэрнатывай, або Беларусь, уяўленая інакш // Arche. № 2 (31), 2004.

- ^ Клімчук Ф. Старадаўняя пісьменнасць і палескія гаворкі // Беларуская лінгвістыка. Вып. 50., 2001. С. 19—24.

- ^ Нельга забі(ы)ць

- ^ Памерла беларуская патрыётка Алеся Фурс. У маладосці яна атрымала 25 гадоў лагера за "Пагоню"281

- ^ Касперович Л. Местные бабушки плакали: "Оставьте нам церковь". Деревянные храмы Беларуси, которые нужно увидеть, TUT.BY, 12 сакавіка 2018 г.

- ^ Template:Літаратура/Дзевяноста пяты (2015) С. 10.

External links[edit]

- Ніна Баршчэўская. Русыфікацыя беларускае мовы ў асьвятленьні газэты «Беларус» // kamunikat.org (in Belarusian)

- Павел Добровольский. Замки, храмы и ратуши. Кто, когда и зачем уничтожил исторический облик крупных городов Беларуси // TUT.BY (in Russian)