Far-right politics in Israel

This article is actively undergoing a major edit for a short while. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. This page was last edited at 19:31, 17 May 2024 (UTC) (5 seconds ago) – this estimate is cached, . Please remove this template if this page hasn't been edited for a significant time. If you are the editor who added this template, please be sure to remove it or replace it with {{Under construction}} between editing sessions. |

Far-right politics in Israel encompasses ideologies such as ultranationalism, Jewish supremacy, Jewish fascism, Jewish fundamentalism, Anti-Arabism,[1] anti-Palestinianism, and ideological movements such as Kahanism

In recent times, the term "far-right" is mainly used to describe advocates of policies such as the expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank, opposition to Palestinian statehood, and imposition of Israeli sovereignty over the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

In association with the 2023 Israeli judicial reform the Likud-led Thirty-seventh government of Israel was frequently described as "Fascist" or "Dictatorial".[2][3][4] Also during 2023 (but almost always separately), many people expressed concern that the policies and actions of the Israeli far right would lead to a "third intifada". Such as Haaretz journalist Amos Harel.[5] But this commentary went largely unnoticed outside of Israel and the middle east.[6]

In 2024, many individuals and groups on the far-right in Israel are advocating for the reoccupation of Gaza following the Israel-Hamas war.[7]

Criticism[edit]

Several journalists and human rights groups such as B'Tselem, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch claim that the ideology advocated by the Israeli far-right are fascist and racist towards Palestinians, Arab citizens of Israel and immigrants. They see it as a danger to democracy, and claim that it uses violence and encourages violation of human rights.[8][9][10][11] President of the United States Joe Biden said Benjamin Netanyahu's government contained "some of the most extreme" members he had ever seen.[12]

During 2022 and 2023, the Likud-led far right coalition was frequently described in authoritarian terms, such as "Fascist", "a dictatorship", and "Stalinist" (for Stalinism's authoritarian aspects).[13]

History[edit]

In Mandatory Palestine (1920–1948)[edit]

Prior to the establishment of Israel, far-right Jewish groups were based on Revisionist Zionism, which promoted the Jewish right to sovereignty over all of Mandatory Palestine through the use of armed struggle.[14] Revisionist Zionism's ideological and cultural roots were influenced by Italian fascism. Ze'ev Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism, believed that Britain could no longer be trusted to advance Zionism, and that Fascist Italy, as a growing political challenger to Britain, was therefore an ally.[15][16]

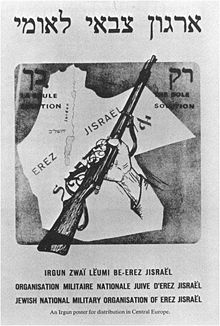

In 1923, Jabotinsky established the Revisionist Zionist youth movement Betar at a meeting in Riga, Latvia.[17] 2 years later in 1925, the Revisionist "Hatzohar" Party was established,[18][19] as a movement that existed separate from the main Zionist movement, the World Zionist Organization.[20] The term "revisionist" referred to a revision of the World Zionist Organization's policies at the time. The Irgun, a Revisionist Zionist paramilitary organization, established by Avraham Tehomi in 1931, opposed British rule over Palestine, and was engaged in acts of terrorism against British officers and Arabs, in an attempt to expel them from the land and achieve Jewish sovereignty.[21][22][23][24] The Irgun joined forces with Betar and Hatzohar in 1937.[25]

The Lehi, also known as the Stern Gang, was a Revisionist Zionist militant group, founded by Avraham Stern in Mandatory Palestine in 1940. The group split from the Irgun, and sought a similar alliance with Fascist Italy.[25] Lehi also believed that Nazi Germany was less of an enemy of the Jews than Britain was, and attempted to form an alliance with the Nazis, proposing a Jewish state based on "nationalist and totalitarian principles, and linked to the German Reich by an alliance".[26] Avraham Stern, then commander of the Lehi, objected to the White Paper of 1939, British plans to restrict Jewish immigration and Jewish land purchase in Palestine, and proposed the creation of a binational Jewish-Arab Palestine. calling for an armed struggle against the British instead.[27][28]

The White Paper's publication also intensified the conflict between the Zionist militias and the British Army; a Jewish general strike was called, attacks were launched against Arabs and British police, telephone services and power lines were sabotaged, and violent speeches of protest were held for several months.[29] A week after the publication of the White Paper of 1939, the Irgun planted an explosive device in the Rex cinema in Jerusalem, injuring 18 people, including 13 Arabs and 3 British police officers. On that same day, 25 Irgun members attacked the Arab village Biyar 'Adas, forced their way into 2 houses, and shot 5 Arab civilians to death.[30]

In 1967[edit]

In the aftermath of the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel captured the Golan Heights, the West Bank, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip.[31] This victory resulted in the revival of "territorial maximalism," with aspirations to annex and settle these new territories.[32] leading some Israeli political leaders to argue for the redefinition of the country's borders in accordance with the vision of Greater Israel.[33] The Movement for Greater Israel, which emerged about a month after the Six-Day War ended, advocated for the control over all of the territories captured during the war, including the Sinai Peninsula, West Bank, and Golan Heights. The members of the movement demanded immediate imposition of Israeli sovereignty over the territories. The supporters of the movement were united by a territorial maximalist ideology.[33] During the summer of 1967, far-right nationalists began to establish settlements in the occupied West Bank to establish a Jewish presence on the land.[34] Menachem Begin's agreement to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt, as well as his initiation of the Autonomy Plan, caused parts of the political right to radicalise and adopt far-right political ideologies.[35]

Kach party (1971–1994)[edit]

The Kach party, founded by Meir Kahane in 1971, was a far-right Orthodox Jewish, Religious Zionist political party in Israel. The party's ideology, known as Kahanism, advocated the transfer of the Arab population from Israel, and the creation of a Jewish theocratic state, in which only Jews have voting rights.[36] Kach additionally argued that Israel should annex the 1967 Israeli-occupied territories because of their religious significance.[37][38] The party's motto, "Rak Kach" lit. 'Only thus', was derived from the motto of the Irgun, a Zionist militant organization active in the 1940s.[37][39] In the 1973 Israeli legislative election, Kach won 0.81% of the total votes, falling short to pass the electoral threshold, which was 1% at the time. In the next elections in 1977, Kach failed once again to win enough votes for parliamentary presence.[40] Kach earned a single seat in the Knesset in the 1984 Israeli legislative election.[41][42]

Shortly after Meir Kahane was sworn in as a member of the Knesset, he made his first media-oriented provocation by announcing his plan to open an emigration office in the Arab village of Umm al-Fahm. He stated that his plan was to offer residents of the village financial incentives to leave their homes and the country.[43] The town declared a general strike shortly after, and roughly 30,000 people, including liberal Jews, arrived at Umm-al-Fahm to prevent Kahane from entering the town. The Israel Police initially decided to accompany Kahane with 1000 police officers as he marched, but later decided to cancel Kahane's march altogether, in concern of negative consequences.[44]

Kach activists frequently entered Arab localities in Israel, distributing propaganda leaflets in demonstrations, provocatively raising the Israeli flag, making Arabs sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence, threatening them against moving to majority-Jewish towns, and convincing Arabs to leave the country.[45] Some of Meir Kahane's legislative initiatives were mostly related to the "Arab problem" in Israel, intending to separate Jews and Arabs in public swimming pools, banning romantic relations between Jews and Arabs, and revoking the citizenship of Arabs in Israel.[46] In his book, "They Must Go", Kahane wrote: "There is only one path for us to take: the immediate transfer of Arabs from Eretz Yisrael. For Arabs and Jews in Eretz Yisrael there is only one answer: separation, Jews in their land, Arabs in theirs. Separation. Only separation."[47]

One bill which he proposed required the imposition of a mandatory death penalty on any non-Jew who either harmed or attempted to harm a Jew, as well as the automatic deportation of the perpetrator's family and the perpetrator's neighbors from Israel and the West Bank.[48] The Supreme of Israel struck down his initiatives, on the grounds that there was no precedent and provision for them in the Basic Laws of Israel.[49] To limit the potential influence of anti-democratic parties such as Kach, the Knesset, in 1985, proposed a new amendment to exclude parties that negate the democratic character of Israel.[49] Kach was later barred from the 1988 elections, and its appeal was denied by the Supreme Court.[49] 1994, following Baruch Goldstein's massacre of 29 Palestinians at the Cave of the Patriarchs, Israel designated Kach, for which Goldstein previously stood as a Knesset Candidate,[50] as a terror organization.[51][52]

Oslo Accords[edit]

The far-right in Israel opposed the Oslo Accords, with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin being assassinated in 1995 by a right-wing Israeli extremist for signing them.[53] Yigal Amir, Rabin's assassin, had opposed Rabin's peace process, particularly the signing of the Oslo Accords, because he felt that an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank would deny Jews their "biblical heritage which they had reclaimed by establishing settlements".[34] Rabin was also criticized by right-wing conservatives and Likud leaders who perceived the peace process as an attempt to forfeit the occupied territories and a surrender to Israel's enemies.[54][55] After the murder, it was revealed that Avishai Raviv, a well-known right-wing extremist at the time, was a Shin Bet agent and informant.[56] Prior to Rabin's murder, Raviv was filmed with a poster of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in an SS uniform.[57][58][59] His mission was to monitor the activities of right-wing extremists, and he allegedly knew of Yigal Amir's plans to assassinate Rabin.[60]

Israeli disengagement from Gaza[edit]

The Israeli disengagement from Gaza, headed by Ariel Sharon, included the removal of all Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip as well as several West Bank settlements, and resulted in protests and riots from Jewish settlers.[61][62][63] Posters covering the streets stated that "Ariel Sharon had no right to give up parts of the Land of Israel". The settlers managed to secure the support of Ovadia Yosef, then-leader of Shas party, who instructed Shas members of the Knesset to vote against the disengagement plan.[64][65] Three settlers burned themselves alive in protest of the disengagement.[66][67][68] By September 12, 2005, the eviction of all settlers from the Gaza Strip and demolition of their houses was completed,[69][70] bringing Israel's 38 years of military rule over the Gaza Strip to a halt.

Founding of Otzma Yehudit[edit]

Otzma Yehudit was founded in 2012 by Michael Ben-Ari, a former member of Kach. In the 2021 Israeli legislative election, Itamar Ben-Gvir, a follower of Kach, was elected to the Knesset as a representative of the Otzma Yehudit party.[71] Since 2022, Ben-Gvir has served as a Minister of National Security, and the party presently holds six seats in the Knesset. Lehava, one of the largest far-right organizations in Israel, advocates for the segregation and oppression of Palestinians. It has also been involved in acts of violence against Palestinians, LGBT individuals, and Christians. Both the United States and the United Kingdom have imposed sanctions on Lehava.[72][73]

Thirty-seventh government of Israel[edit]

The 37th Cabinet of Israel, formed on December 29, 2022, following the Knesset election on November 1, 2022, has been described as the most right-wing government in Israeli history,[74][75][76][77] as well as Israel's most religious government.[78][79] The coalition government consists of seven parties—Likud, United Torah Judaism, Shas, Religious Zionist Party, Otzma Yehudit, Noam, and National Unity—and is led by Benjamin Netanyahu.[80]

Judicial reforms[edit]

In 2023, as part of a campaign for judicial reform, a bill known as the "reasonableness" bill was passed in Israel. This controversial law limited the power of the Supreme Court to declare government decisions unreasonable.[81] In one instance, more than 80,000 Israeli protesters rallied in Tel Aviv against the far-right government's plans to overhaul the judicial system.[82] In early 2024, the Supreme Court of Israel struck down the reform[83] on the grounds that it would deal a "severe and unprecedented blow to the core characteristics of the State of Israel as a democratic state".[84]

Israel-Hamas war[edit]

Predicted provocation of a "third intifada"[edit]

In early 2023 many people expressed concern that the policies and actions of the Israeli far right would lead to a "third intifada". Such as Haaretz journalist Amos Harel, "Will far-right minister Itamar Ben-Gvir’s chutzpah trigger a third intifada?".[5] Due to events such as the Huwara rampage and Ben Gvir's activities at Al-Aqsa (see details above).

In March 2023 Yoav Gallant warned that something like 7 October attacks was looming, and was almost fired by Netanyahu for doing so.[85]

The reaction to West Bank violence[edit]

Despite the 7 October attacks eminating from the Gaza Strip, most of the reasons Mohammed Deif gave for the attack were events in the West Bank and Jerusalem, such as Israeli settler violence and the expansion of the Israeli settlements.[86][87][88] "The Israeli occupation has seized thousands of dunums of Palestinian territory and uprooted Palestinian citizens from their homes and lands to build illegal settlements while providing cover for colonial settlers to rampage through Palestinian towns villages and attack and terrorise the Palestinian citizens."[86] Al Qassam's English version included the motivations, but left out what they planned to do about it.[87]

February 2023 Huwara rampage[edit]

On 26 February 2023, hundreds of Israeli settlers went on a violent late-night rampage in Huwara and other Palestinian villages in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, leaving one civilian dead and 100 other Palestinians injured, four critically, and the town ablaze.[89][90] It was the worst attack stemming from Israeli settler violence in the northern West Bank in decades.[91][92][93]

Israeli soldiers were in the area while the rampage by the settlers unfolded and did not intervene.[90] The rampage was called a pogrom by an Israeli commander in charge of the area.[94] The attack followed the deadly shooting of two Israeli settlers the same day by an unidentified attacker in the area.[95][89] The same day, Israeli and Palestinian officials issued a joint declaration in Aqaba, Jordan to counter the recent round of Israeli–Palestinian violence.[91][92][96]

In the rampage's aftermath, Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, a settler leader in charge of the administration of the West Bank,[97] called for Huwara to be "wiped out" by the Israeli army.[98][99] Condemnations from the United States, European Union, and Arab countries led to Smotrich retracting his comments and claiming they were said in the heat of the moment.[94][100]

Ben Gvir leading incursions on Al Aqsa Mosque[edit]

The Al-Aqsa mosque compound,[a] is one of the holiest sites in Islam and a Palestinian national symbol.[101] A substantial proportion of Al-Qassam's stated reasons for the 7 October attacks related to increased hostility at Al-Aqsa.[86][87] They called the initial attack, and their role in the subsequent war "Al-Aqsa Flood".[87]

Before October 2023, National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir led a groups of up to a thousand ultra nationalist Israeli settlers to the Al-Aqsa compound in East Jerusalem at least four times.[101]

Israel-Hamas war[edit]

Al Qassam's stated reasons for the 7 October attacks[edit]

The 7 October 2023 speech and written statement from Mohammed Deif announcing "Operation Al-Aqsa Flood" included a very long list of objections to recent actions by Israel.[87][88] He did not name individuals or political parities, but referred to events and actions that had escalated the conflict, many of which had been previously identified as provocative (see above).[86]

Statements from far right ministers about the IDF response[edit]

Israel's far-right ministers have made controversial comments during the 2023 Israel–Hamas war.

- Agriculture Minister Avi Dichter told Israeli Channel 12 that the war would be "Gaza's Nakba," using the Arabic word for "catastrophe" that many use to describe the 1948 displacement of roughly 700,000 Palestinians.[102][103]

- Israel's Heritage Minister Amihai Eliyahu said in an interview that dropping a nuclear bomb on the Gaza Strip was "one of the possibilities".[104][105]

- Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich said Palestinians should be excluded from "security zones" in the occupied West Bank even to "harvest olives". He has also called for the creation of "sterile security zones" around settlements in the West Bank to "prevent Arabs from entering".[106][107]

- Israel's Minister for Advancement of Women May Golan said "I am personally proud of the ruins of Gaza, and that every baby, even 80 years from now, will tell their grandchildren what the Jews did."[108]

In May 2024, many individuals and groups on the far-right in Israel are advocating for the reoccupation of Gaza following the Israel-Hamas war.[109]

Massively increased availability of guns[edit]

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by AnomieBOT (talk | contribs) 5 seconds ago. (Update timer) |

anti LGBTQ actions[edit]

Bezalel Smotrich[edit]

This article needs to be updated. (May 2024) |

In 2015, Bezalel Smotrich, a Knesset member from the Orthodox-religious Jewish Home party, referred to LGBT people as "abnormal", stating: "At home, everyone can be abnormal, and people can form whatever family unit they want. But they can't make demands from me, as the state." In the same discussion, he told the audience, "I am a proud homophobe".[110] He later apologized, and retracted his statement, saying: "Someone shouted from the crowd, and I responded inattentively".[111][112]

In August 2015, Smotrich accused LGBT organizations of controlling the media, claiming they use their control to gain public sympathy and silence those who share his conservative views.[113] An Israeli NGO, Ometz, filed a complaint with the Knesset Ethics Committee to intervene and investigate Smotrich's comments.[114]

Jerusalem Pride "Beast Parade"[edit]

In July 2015, after the Jerusalem LGBT pride stabbing, Smotrich called it a "beast parade", and refused to retract his homophobic remarks.[115][116]

Arieh King[edit]

In June 2019, Jerusalem city inspectors took down a Pride banner hung by the US embassy for LGBTQ Pride Month. Deputy mayor Arieh King had ordered the removal.[117]

Rafi Peretz[edit]

In July 2019, interim Education Minister Rafi Peretz attracted criticism from when he endorsed conversion therapy. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu rejected Peretz's comments as unacceptable, saying that they "do not represent [his] government's position" and that "[he] made it clear to him that the Israeli educational system will continue to accept all Jewish children whoever they are and without any difference based on sexual orientation." Thousands of Israeli teachers signed a petition demanding his resignation,[52] and more than a thousand people protested his comments in Tel Aviv and in Peretz's hometown, calling for his dismissal.[118] Days layer, Peretz backtracked from his comments, labelling conversion therapy "inappropriate", but added that "individuals with a homosexual orientation have the right to receive professional help".[119][120][34][33][49][excessive citations]

Shlomo Benizri[edit]

On 20 February 2008, Shlomo Benizri, a Knesset member from the religious Shas party, a member of Prime Minister Ehud Olmert's ruling coalition, blamed earthquakes that had recently struck the Middle East on the activities of homosexuals. Benizri said in a Knesset plenary session, "Why do earthquakes happen? ... One of the reasons is the things to which the Knesset gives legitimacy, to sodomy." He recommended that instead of merely reinforcing buildings to withstand earthquakes, the Government should pass legislation to outlaw "perversions like adoptions by gay couples". Benizri stated that, "A cost-effective way of averting earthquake damage would be to stop passing legislation on how to encourage homosexual activity in the State of Israel, which anyways causes earthquakes."[121]

Courses of action[edit]

The far-right in Israel have used a variety of ways over the years to achieve their political goals. These include far-right parties such as Kach, Otzma Yehudit, and Eretz Yisrael Shelanu being represented in the Knesset, Israel's parliament.[122] Establishment of unauthorized Israeli outposts in the West Bank is also common among far-right extremist groups, such as the Hilltop Youth.[118][120][119][123] Jewish extremist terrorism was carried out by extremists within Judaism, including the assassination of Palestinian mayors by the Jewish Underground group, the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre, the murder of the boy Mohammed Abu Khdeir, and the Duma arson attack.[124][125] Further, "price tag attacks" have been committed in the occupied West Bank by extremist Israeli settler youths against Palestinian Arabs, and to a lesser extent against left-wing Israelis, Israeli Arabs, Christians, and Israeli security forces.[126][127] Finally, political violence committed by far-right extremists, such as the murder of Emil Grunzweig, the attempted assassination of Zeev Sternhell, and the Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin.[128][129]

See also[edit]

- One-state solution

- Israeli settler violence: Huwara rampage

- Population transfer

- Palestinian genocide accusation

- Racism in Israel

- Zionist political violence

- Jewish extremist terrorism

- Jewish fundamentalism

- Jewish views on religious pluralism

- Judaism and violence

- Judaism and politics

- Politics of Israel

References[edit]

- ^ Sprinzak, Ehud (1993). The Israeli Radical Right: History, Culture, and Politics (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 2, 22–23. ISBN 9780429034404.

- ^ Klein, Yossi (February 10, 2023). "Do not march blindly into dictatorship". Haaretz. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Klein, Yossi (February 17, 2023). "Germany 1933, Israel 2023". Haaretz. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Zananiri, Elias (October 3, 2023). "Israeli Neo-Fascism threatens Israelis and Palestinians alike". Haaretz. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Harel, Amos (February 3, 2023). "Will far-right minister Itamar Ben-Gvir's chutzpah trigger a third intifada?". Haaretz. Retrieved May 16, 2024. Cite error: The named reference "Chutzpah" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "A Third Intifada could be coming, but you won't learn about it in the New York Times". Mondoweiss. December 5, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Peled, Margherita Stancati and Anat. "Israel's Far Right Plots a 'New Gaza' Without Palestinians". WSJ. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ Guyer, Jonathan (January 20, 2023). "Israel's new right-wing government is even more extreme than protests would have you think". Vox. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Shakir, Omar (April 27, 2021). "A Threshold Crossed". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ "Who is Israel's far-right, pro-settler Security Minister Ben-Gvir?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Nechin, Etan (January 9, 2024). "The far right infiltration of Israel's media is blinding the public to the truth about Gaza". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Gritten, David (July 10, 2023). "Biden criticises 'most extreme' ministers in Israeli government". BBC. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ https://www.haaretz.com/opinion/2023-01-12/ty-article-opinion/.premium/netanyahus-stalinist-purge-threatens-israeli-democracy/00000185-a2b0-d7cf-afef-a6fa4b1e0000

- ^ Zouplna, Jan (2008). "Revisionist Zionism: Image, Reality and the Quest for Historical Narrative". Middle Eastern Studies. 44 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1080/00263200701711754. ISSN 0026-3206.

- ^ Kaplan, Eran (2005). The Jewish radical right: Revisionist Zionism and its ideological legacy. Studies on Israel. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 21, 149–150, 156. ISBN 978-0-299-20380-1.

- ^ Brenner, Lenni (1983). "Zionism-Revisionism: The Years of Fascism and Terror". Journal of Palestine Studies. 13 (1): 66–92. doi:10.2307/2536926. JSTOR 2536926 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Puchalski, P. (2018). "Review: Jabotinsky's Children: Polish Jews and the Rise of Right-Wing Zionism". The Polish Review. 63 (3). University of Illinois Press: 88–91. doi:10.5406/polishreview.63.3.0088. JSTOR 10.5406/polishreview.63.3.0088.

- ^ Revisionist Zionists, YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

- ^ Ze'ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Tzahor, Zeev (1988). "The Struggle between the Revisionist Party and the Labor Movement: 1929-1933". Modern Judaism. 8 (1): 15–25. ISSN 0276-1114.

- ^ Leonard Weinberg, Ami Pedahzur, Religious fundamentalism and political extremism, Routledge, p. 101, 2004.

- ^ J. Bowyer Bell, Moshe Arens, Terror out of Zion,p. 39, 1996 edition

- ^ (in Hebrew)Y. 'Amrami, A. Melitz, דברי הימים למלחמת השחרור ("History of the War of Independence", Shelach Press, 1951. (a sympathetic account of events, mostly related to Irgun and Lehi).

- ^ Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (1993). Political Assassinations by Jews: A Rhetorical Device for Justice. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. p. 204.

- ^ a b Sofer, Sasson; Shefer-Vanson, Dorothea (1998). Zionism and the foundations of Israeli diplomacy. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-0-521-63012-2.

- ^ Leslie Stein,The Hope Fulfilled: The Rise of Modern Israel, Greenwood Publishing Group 2003 pp. 237–238.

- ^ Medoff, Rafael; Waxman, Chaim I. (2013). Historical dictionary of Zionism. Taylor & Francis. p. 183. ISBN 9781135966492.

- ^ Colin Shindler (1995). The Land beyond Promise: Israel, Likud and the Zionist dream. I.B. Tauris. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86064-774-1.

- ^ Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Jewish Problems in Palestine and Europe; United Nations, eds. (1991). A Survey of Palestine. Washington, D.C: Institute for Palestine Studies. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-88728-211-9.

- ^ "The Palestine Post | Page 1 | 30 May 1939 | Newspapers | The National Library of Israel". www.nli.org.il. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ "Milestones: 1961–1968". Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

Between June 5 and June 10, Israel defeated Egypt, Jordan, and Syria and occupied the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights

- ^ Sprinzak, Ehud (1991). The Ascendance of Israel's Radical Right. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-19-505086-8.

- ^ a b c Pedahzur, Ami (2012). The Triumph of Israel's Radical Right. Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-19-974470-1.

- ^ a b c Smith, Charles D. Palestine and the Arab-Israeli Conflict A History with Documents, ISBN 0-312-43736-6, pp. 458

- ^ Sprinzak, Ehud (1989). "The Emergence of the Israeli Radical Right". Comparative Politics. 21 (2): 172–173. doi:10.2307/422043. ISSN 0010-4159. JSTOR 422043.

- ^ Martin, Gus; Kushner, Harvey W., eds. (2011). The Sage encyclopedia of terrorism (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications. p. 321. ISBN 978-1-4129-8016-6.

- ^ a b Medoff, Rafael; Chaim, I. Waxman (2000). Historical Dictionary of Zionism. Taylor & Francis. p. 100. ISBN 9781135966423.

- ^ Meir Kahane (1987). Uncomfortable Questions for Comfortable Jews. Lyle Stuart. p. 270. ISBN 978-0818404382.

The Jew is forbidden to give up any part of the Land of Israel, which has been liberated. The land belongs to the G-d of Israel, and the Jew, given it by G-d, has no right to give away any part of it. All the areas liberated in 1967 will be annexed and made part of the State of Israel. Jewish settlement in every part of the land, including cities that today are sadly Judenrein, will be unlimited.

- ^ Čejka, Marek; Roman, Kořan. Rabbis of Our Time: Authorities of Judaism in the Religious and Political Ferment of Modern Times. Taylor & Francis. p. 89. ISBN 9781317605447.

- ^ Weinberg, Leonard; Pedahzur, Ami (2003). Political parties and terrorist groups. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-415-26871-4.

- ^ Peled, Yoav (June 1992). "Ethnic Democracy and the Legal Construction of Citizenship: Arab Citizens of the Jewish State". American Political Science Review. 86 (2): 438. doi:10.2307/1964231. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1964231.

- ^ "Parliamentary Groups in the Knesset". August 15, 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Cohen-Almagor, Raphael (2002). "The Offense to Sensibilities Argument as Grounds for Limiting Free Expression: The Israeli Experience". International Journal of Politics and Ethics. 2: 13. SSRN 304568 – via Social Science Research Network.

- ^ Amara, Muhammad Hasan (2018). Arabic in Israel: language, identity and conflict. Routledge studies in language and identity. Abingdon, Oxon New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. pp. 124, 126. ISBN 978-1-138-06355-6.

- ^ Smooha, Sammy (1992). Arabs and Jews in Israel. 2: Change and continuity in mutual intolerance. Westview Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-8133-0756-5.

- ^ Cohen-Almagor, Raphael (1994). The Boundaries of Liberty and Tolerance: The Struggle Against Kahanism in Israel. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1258-2.

- ^ Kahane, Meir (1981). They Must Go. Grosset & Dunlap. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-448-12026-3.

- ^ Pedahzur, Ami (2002). The Israeli response to Jewish extremism and violence. Manchester University Press. JSTOR j.ctt155j609.

- ^ a b c d Seltzer, Nicholas A.; Wilson, Steven Lloyd, eds. (2023). Handbook on democracy and security. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-83910-020-8.

- ^ "בחירות 1984". Israel Democracy Institute (in Hebrew). Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Shah, Syed Adrian Ali (2005). "Religious Terrorism in Other Faiths". Strategic Studies. 25 (2): 135. ISSN 1029-0990. JSTOR 45242597.

- ^ a b Lewis, Neil (October 18, 2006). "Appeals Court Upholds Terrorist Label for a Jewish Group". The New York Times.

- ^ Rabin, Leah (1997). Rabin: His Life, Our Legacy. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 7, 11–12. ISBN 0-399-14217-7.

- ^ Newton, Michael (2014). "Rabin, Yitzhak". Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 450. ISBN 978-1-61-069285-4.

- ^ Tucker, Ernest (2016). The Middle East in Modern World History. Routledge. pp. 331–32. ISBN 978-1-31-550823-8.

- ^ Ephron, Dan (2015). Killing a king: the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin and the remaking of Israel (1st ed.). New York London: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-393-24209-6.

- ^ Barnea, Avner (January 2, 2017). "The Assassination of a Prime Minister–The Intelligence Failure that Failed to Prevent the Murder of Yitzhak Rabin". The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs. 19 (1): 37. doi:10.1080/23800992.2017.1289763. ISSN 2380-0992.

- ^ Hellinger, Moshe; Hershkowitz, Isaac; Susser, Bernard (2018). Religious Zionism and the settlement project: ideology, politics, and civil disobedience. Albany: SUNY Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-4384-6839-6.

- ^ Ex-Undercover Agent Charged as a Link in Rabin Killing, The New York Times, April 26, 1999

- ^ Cohen-Almagor, Raphael (2006). The scope of tolerance: studies on the costs of free expression and freedom of the press. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-35758-6.

- ^ Kumaraswamy, P. R. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Historical dictionaries of war, revolution, and civil unrest (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4422-5169-4.

4 August: Security forces prevent thousands of Israeli protesters from marching into Gaza settlements

- ^ "Thousands protest Israel's Gaza withdrawal". NBC News. June 27, 2005. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ Lis, Jonathan (January 25, 2010). "Israel to expunge criminal records of 400 Gaza pullout opponents". Haaretz. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ Milton-Edwards, Beverley (2009). The Israeli-Palestinian conflict: a people's war. London ; New York: Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-415-41044-1. OCLC 166379384.

- ^ Reichner, Elyashiv (2010). Katom ha-maʼavaḳ: Gush Ḳaṭif be-maʻarakhah. Tel-Aviv: Yediʻot aḥaronot : Sifre ḥemed. p. 64. ISBN 978-965-545-165-8. OCLC 651600751.

- ^ "מת גבר ששרף עצמו בגלל הפינוי" [Man who set himself on fire in protest of the disengagement - pronounced dead]. www.makorrishon.co.il. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ Hasson, Nir (August 18, 2005). "מפגינת ימין הציתה עצמה; מצבה קשה". הארץ (in Hebrew). Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ וייס, אפרת (September 6, 2005). "מת מפצעיו הצעיר שהצית עצמו בגלל ההתנתקות". Ynet (in Hebrew). Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Rynhold, Jonathan; Waxman, Dov (2008). "Ideological Change and Israel's Disengagement from Gaza". Political Science Quarterly. 123 (1): 11. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2008.tb00615.x. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 20202970.

- ^ "Demolition of Gaza Homes Completed". Ynetnews.com. September 1, 2005. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- ^ "Itamar Ben-Gvir: Israeli far-right leader set to join new coalition". BBC. November 25, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "UK sanctions extremist groups and individuals for settler violence in the West Bank". GOV.UK. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ "US sanctions Lehava leader, fundraisers for violent settlers". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. April 19, 2024. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ * Kershner, Isabel; Kingsley, Patrick (November 1, 2022). "Israel Election: Exit Polls Show Netanyahu With Edge in Israel's Election". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- Reich, Eleanor H. (November 16, 2022). "Israel swears in new parliament, most right-wing in history". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Shalev, Tal (February 3, 2023). "The most right-wing coalition in Israel's history had a stormy first month". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ * "Israel Swears in New Parliament, Most Right-Wing in History". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press (AP). 2022. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

Israel has sworn in its most religious and right-wing parliament

- Lieber, Dov; Raice, Shayndi; Boxerman, Aaron (2022). "Behind Benjamin Netanyahu's Win in Israel: The Rise of Religious Zionism". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

Israel's most right-wing and religious government in its history

- "Netanyahu Government: West Bank Settlements Top Priority". VOA. Associated Press (AP). 2022. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

the most religious and hardline in Israel's history

- Lieber, Dov; Raice, Shayndi; Boxerman, Aaron (2022). "Behind Benjamin Netanyahu's Win in Israel: The Rise of Religious Zionism". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Carrie Keller-Lynn (December 21, 2022). ""I've done it": Netanyahu announces his 6th government, Israel's most hardline ever". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Tal, Rob Picheta,Hadas Gold,Amir (December 29, 2022). "Benjamin Netanyahu sworn in as leader of Israel's likely most right-wing government ever". CNN. Archived from the original on February 28, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ * Maltz, Judy (November 3, 2022). "Will Israel Become a Theocracy? Religious Parties Are Election's Biggest Winners". Haaretz. Archived from the original on November 7, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- Levinthal, Batya (January 4, 2023). "Poll: 70% of secular Israelis worry about their future under new gov". i24News. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

Netanyahu's new government, deemed the most religious and right-wing in the country's history.

- Levinthal, Batya (January 4, 2023). "Poll: 70% of secular Israelis worry about their future under new gov". i24News. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Gross, Judah Ari (November 4, 2022). "Israel poised to have its most religious government; experts say no theocracy yet". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Elections and Parties". en.idi.org.il. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Gold, Hadas; Greene, Richard Allen; Tal, Amir (July 24, 2023). "Israel passed a bill to limit the Supreme Court's power. Here's what comes next". CNN. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ McGarvey, Emily (January 14, 2023). "Over 80,000 Israelis protest against Supreme Court reform". BBC. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zack (January 3, 2024). "Israel's Supreme Court just overturned Netanyahu's pre-war power grab". Vox. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Edwards, Christian (January 2, 2024). "What we know about Israel's Supreme Court ruling on Netanyahu's judicial overhaul". CNN. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Tibon, Amir (May 16, 2024). "Israel's real problem is that Netanyahu and his far-right allies prefer Hamas". Haaretz. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Statement by Al-Qassam Brigades Chief of Staff Mohammed Deif". Ezzedeen AL-Qassam Brigades (English). EQB Information Office. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "We announce the start of the al-Aqsa Flood". Fondazione Internazionale Oasis. December 13, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

- ^ a b "خطاب "طوفان الأقصى"". مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية (Institute for Palestine Studies) (in Arabic). Institute for Palestine Studies. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Kingsley, Patrick; Kershner, Isabel (February 27, 2023). "Revenge Attacks After Killing of Israeli Settlers Leave West Bank in Turmoil". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Breiner, Josh (February 28, 2023). "The Chaos in Hawara Didn't End on the Night of the Riots, nor Did the Israeli Army's Incompetence". Haaretz. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ a b McKernan, Bethan (February 27, 2023). "Israeli settlers rampage after Palestinian gunman kills two". The Guardian. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Mohammed, Majdi; Ben Zion, Ilan (February 27, 2023). "Israel beefs up troops after unprecedented settler rampage". AP NEWS. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Bateman, Tom (February 27, 2023). "Hawara: 'What happened was horrific and barbaric'". BBC News. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

israeli_campaign_2023_03_02_apwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gritten, David (February 27, 2023). "Settlers rampage in West Bank villages after Israelis killed". BBC News. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ McKernan, Bethan (February 26, 2023). "Israeli and Palestinian officials express 'readiness' to work to stop violence". The Guardian. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

emboldened_2023_03_02_washpostwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

justifieswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

us_prods_2023_03_02_timesofisraelwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

dc_visit_2023_03_03_timesofisraelwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Harb, Farah Najjar,Ali (July 27, 2023). "Israeli far-right minister leads incursion of Al-Aqsa compound". Al Jazeera. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tov, Michael Hauser (November 12, 2023). "'We're rolling out Nakba 2023,' Israeli minister says on northern Gaza Strip evacuation". Haaretz. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Da Silva, Chantal (November 14, 2023). "Israel right-wing ministers' comments add fuel to Palestinian fears". NBC News. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Lederer, Edith M. (November 14, 2023). "China, Iran, Arab nations condemn Israeli minister's statement about dropping a nuclear bomb on Gaza". AP News. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Reporter, Staff. "Extremist Israeli minister renews call to hit Gaza with 'nuclear bomb'". Extremist Israeli minister renews call to hit Gaza with 'nuclear bomb'. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "Far-right minister Smotrich calls for 'sterile zones' free of Palestinians near settlements". Middle East Eye. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Burke, Jason; Taha, Sufian (November 30, 2023). "'No work and no olives': harvest rots as West Bank farmers cut off from trees". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Bhat, Sadiq. "'Proud of ruins of Gaza': Israeli minister rejoices at Palestine's distress". 'Proud of ruins of Gaza': Israeli minister rejoices at Palestine's distress. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Peled, Margherita Stancati and Anat. "Israel's Far Right Plots a 'New Gaza' Without Palestinians". WSJ. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ "Jewish Home hopeful boasts of being 'proud homophobe'". The Times of Israel. February 23, 2015. Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "MK Smotrich: The government I'll be part of, will not recognize same-sex couples". Nana10. April 19, 2015. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015.

- ^ "Netanyahu Government will not recognize same-sex marriage". GoGay.co.il. April 19, 2015. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Karni, Tuval (August 15, 2018). "Bayit Yehudi MK: Gays control the media". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Pileggi, Tamar (August 16, 2015). "NGO files complaint against MK for 'Gays control the media' remark". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Smotrich: LGBT community attacks, slanders anyone who thinks differently from them". The Jerusalem Post. August 2, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Right-wing MK: Jerusalem Pride Parade Is an 'Abomination'". Haaretz. August 2, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Nir Hasson: Jerusalem City Inspectors Take Down U.S. Embassy Banner for LGBTQ Pride Month. In: Haaretz, 24 June 2020.

- ^ a b Pietromarchi, Virginia; Haddad, Mohammed. "How Israeli settlers are expanding illegal outposts amid Gaza war". Al Jazeera. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Magid, Jacob (July 23, 2017). "Work starts on new outpost outside Halamish after deadly terror attack". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "Israeli settlers establish new outpost in West Bank". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Shas MK blames gays for recent earthquakes in the region". Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ^ Weinblum, Sharon (January 30, 2015). Security and Defensive Democracy in Israel: A Critical Approach to Political Discourse. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-58450-6.

- ^ "Hilltop Youth push to settle West Bank". August 18, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

- ^ Pedahzur, Ami (2009). Jewish terrorism in Israel. Internet Archive. New York : Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15446-8.

- ^ Burgess, Mark (May 20, 2004). "Explaining Religious Terrorism Part 1". studies.agentura.ru. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Gavlak, Dale (May 13, 2014). "'Price Tag' Israeli Extremists Target Christians". Christianity Today. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Yifa Yaakov, 'Arab Israeli complains of Galilee price tag attack,' The Times of Israel 21 April 2014,

- ^ Hasson, Nir (February 10, 2013). "Daughter of slain peace activist Grunzweig: Israel imposes terror on its citizens". Haaretz. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Rabin, Lea (1997). Rabin : our life, his legacy. Internet Archive. New York : G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-399-14217-8.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).