Netherlands in the Early Middle Ages

The Netherlands in the early Middle Ages was inhabited by various Germanic tribes, including the Frisians, who played a significant role in the development of the region and its Christianisation and eventual incorporation into the Frankish Empire.

The settlers in the northern Netherlands and northwest part of Germany established the Kingdom of the Frisians, adopting the name from the previous inhabitants, with the prosperous trading North Sea trading center of Dorestad playing a vital role. The Franks eventually conquered the area, although its recent doubt has been cast on how distinct they in fact were from other Germanic groups such as the Frisians and Saxons.

Frisians[edit]

As climatic conditions improved, there was another mass migration of Germanic peoples into the area from the east. This is known as the "Migration Period" (Volksverhuizingen). The northern Netherlands received an influx of new migrants and settlers, mostly Saxons, but also Angles and Jutes. Many of these migrants did not stay in the northern Netherlands but moved on to England and are known today as the Anglo-Saxons. The newcomers who stayed in the northern Netherlands would eventually be referred to as "Frisians", although they were not descended from the ancient Frisii. These new Frisians settled in the northern Netherlands and would become the ancestors of the modern Frisians.[1][2] (Because the early Frisians and Anglo-Saxons were formed from largely identical tribal confederacies, their respective languages were very similar. Old Frisian is the most closely related language to Old English[3] and the modern Frisian dialects are in turn the closest related languages to contemporary English.) By the end of the 6th century, the Frisian territory in the northern Netherlands had expanded west to the North Sea coast and, by the 7th century, south to Dorestad. During this period most of the northern Netherlands was known as Frisia. This extended Frisian territory is sometimes referred to as Frisia Magna (or Greater Frisia).

In the 7th and 8th centuries, the Frankish chronologies mention this area as the kingdom of the Frisians. This kingdom comprised the coastal provinces of the Netherlands and the German North Sea coast. During this time, the Frisian language was spoken along the entire southern North Sea coast. The 7th-century Frisian Kingdom (650–734) under King Aldegisel and King Redbad, had its centre of power in Utrecht.

Dorestad was the largest settlement (emporia) in northwestern Europe. It had grown around a former Roman fortress. It was a large, flourishing trading place, three kilometers long and situated where the rivers Rhine and Lek diverge southeast of Utrecht near the modern town of Wijk bij Duurstede.[4][5] Although inland, it was a North Sea trading centre that primarily handled goods from the Middle Rhineland.[5][6] Wine was among the major products traded at Dorestad, likely from vineyards south of Mainz.[6] It was also widely known because of its mint. Between 600 and around 719 Dorestad was often fought over between the Frisians and the Franks.

Franks[edit]

After Roman government in the area collapsed, the Franks expanded their territories until there were numerous small Frankish kingdoms, especially at Cologne, Tournai, Le Mans and Cambrai.[7][8] The kings of Tournai eventually came to subdue the other Frankish kings. By the 490s, Clovis I had conquered and united all the Frankish territories to the west of the Meuse, including those in the southern Netherlands. He continued his conquests into Gaul.

After the death of Clovis I in 511, his four sons partitioned his kingdom amongst themselves, with Theuderic I receiving the lands that were to become Austrasia (including the southern Netherlands). A line of kings descended from Theuderic ruled Austrasia until 555, when it was united with the other Frankish kingdoms of Chlothar I, who inherited all the Frankish realms by 558. He redivided the Frankish territory amongst his four sons, but the four kingdoms coalesced into three on the death of Charibert I in 567. Austrasia (including the southern Netherlands) was given to Sigebert I. The southern Netherlands remained the northern part of Austrasia until the rise of the Carolingians.

The Franks who expanded south into Gaul settled there and eventually adopted the Vulgar Latin of the local population.[9] However, a Germanic language was spoken as a second tongue by public officials in western Austrasia and Neustria as late as the 850s. It completely disappeared as a spoken language from these regions during the 10th century.[10] During this expansion to the south, many Frankish people remained in the north (i.e. southern Netherlands, Flanders and a small part of northern France). A widening cultural divide grew between the Franks remaining in the north and the rulers far to the south in what is now France.[8] Salian Franks continued to reside in their original homeland and the area directly to the south and to speak their original language, Old Frankish, which by the 9th century had evolved into Old Dutch.[9] A Dutch-French language boundary came into existence (but this was originally south of where it is today).[9][8] In the Maas and Rhine areas of the Netherlands, the Franks had political and trading centres, especially at Nijmegen and Maastricht.[8] These Franks remained in contact with the Frisians to the north, especially in places like Dorestad and Utrecht.

Modern doubts about the traditional Frisian, Frank and Saxon distinction[edit]

In the late 19th century, Dutch historians believed that the Franks, Frisians, and Saxons were the original ancestors of the Dutch people. Some went further by ascribing certain attributes, values and strengths to these various groups and proposing that they reflected 19th-century nationalist and religious views. In particular, it was believed that this theory explained why Belgium and the southern Netherlands (i.e. the Franks) had become Catholic and the northern Netherlands (Frisians and Saxons) had become Protestant. The success of this theory was partly due to anthropological theories based on a tribal paradigm. Being politically and geographically inclusive, and yet accounting for diversity, this theory was in accordance with the need for nation-building and integration during the 1890–1914 period. The theory was taught in Dutch schools.

However, the disadvantages of this historical interpretation became apparent. This tribal-based theory suggested that external borders were weak or non-existent and that there were clear-cut internal borders. This origins myth provided an historical premise, especially during the Second World War, for regional separatism and annexation to Germany. After 1945 the tribal paradigm lost its appeal for anthropological scholars and historians. When the accuracy of the three-tribe theme was fundamentally questioned, the theory fell out of favour.[11]

Due to the scarcity of written sources, knowledge of this period depends to a large degree on the interpretation of archaeological data. The traditional view of a clear-cut division between Frisians in the north and coast, Franks in the south and Saxons in the east has proven historically problematic.[12][13][14] Archeological evidence suggests dramatically different models for different regions, with demographic continuity for some parts of the country and depopulation and possible replacement in other parts, notably the coastal areas of Frisia and Holland.[15] Its uncertain which language gave rise to Old Dutch, but it is believed to have been spoken by the Salian Franks and is similar to other Germanic languages.[16] However, the development of Old Dutch is poorly understood as there are few surviving texts in Old Dutch or the language spoken by the Franks. Old Dutch made the transition to Middle Dutch around 1150.[9]

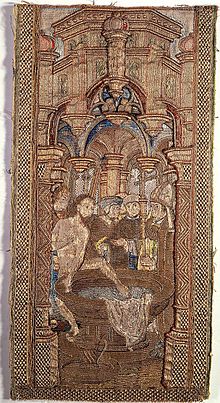

Christianity arrived in the Netherlands with the Romans and continued in Maastricht even after the withdrawal of the Romans, while the Franks became Christians after Clovis I converted to Catholicism in 496. Hiberno-Scottish and Anglo-Saxon missionaries have also played an important role in converting the Frankish and Frisian peoples to Christianity by the 8th century.

Frankish dominance and incorporation into the Holy Roman Empire[edit]

In the early 8th century the Frisians came increasingly into conflict with the Franks to the south, resulting in a series of wars in which the Frankish Empire eventually subjugated Frisia. In 734, at the Battle of the Boarn, the Frisians in the Netherlands were defeated by the Franks, who thereby conquered the area west of the Lauwers. The Franks then conquered the area east of the Lauwers in 785 when Charlemagne defeated Widukind.

The linguistic descendants of the Franks, the modern Dutch -speakers of the Netherlands and Flanders, seem to have broken with the endonym "Frank" around the 9th century. By this time Frankish identity had changed from an ethnic identity to a national identity, becoming localized and confined to the modern Franconia and principally to the French province of Île-de-France.[17]

Although the people no longer referred to themselves as "Franks", the Netherlands was still part of the Frankish empire of Charlemagne. Indeed, because of the Austrasian origins of the Carolingians in the area between the Rhine and the Maas, the cities of Aachen, Maastricht, Liège and Nijmegen were at the heart of Carolingian culture.[8] Charlemagne maintained his palatium[18] in Nijmegen at least four times.

The Carolingian empire would eventually include France, Germany, northern Italy and much of Western Europe. In 843, the Frankish empire was divided into three parts, giving rise to West Francia in the west, East Francia in the east, and Middle Francia in the centre. Most of what is today the Netherlands became part of Middle Francia; Flanders became part of West Francia. This division was an important factor in the historical distinction between Flanders and the other Dutch-speaking areas.

Middle Francia (Latin: Francia media) was an ephemeral Frankish kingdom that had no historical or ethnic identity to bind its varied peoples. It was created by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, which divided the Carolingian Empire among the sons of Louis the Pious. Situated between the realms of East and West Francia, Middle Francia comprised the Frankish territory between the rivers Rhine and Scheldt, the Frisian coast of the North Sea, the former Kingdom of Burgundy (except for a western portion, later known as Bourgogne), Provence and the Kingdom of Italy.

Middle Francia fell to Lothair I, the eldest son and successor of Louis the Pious, after an intermittent civil war with his younger brothers Louis the German and Charles the Bald. In acknowledgement of Lothair's Imperial title, Middle Francia contained the imperial cities of Aachen, the residence of Charlemagne, as well as Rome. In 855, on his deathbed at Prüm Abbey, Emperor Lothair I again partitioned his realm amongst his sons. Most of the lands north of the Alps, including the Netherlands, passed to Lothair II and consecutively were named Lotharingia. After Lothair II died in 869, Lotharingia was partitioned by his uncles Louis the German and Charles the Bald in the Treaty of Meerssen in 870. Although some of the Netherlands had come under Viking control, in 870 it technically became part of East Francia, which became the Holy Roman Empire in 962.

Viking raids[edit]

In the 9th and 10th centuries, the Vikings raided the largely defenceless Frisian and Frankish towns lying on the coast and along the rivers of the Low Countries. Although Vikings never settled in large numbers in those areas, they did set up long-term bases and were even acknowledged as lords in a few cases. In Dutch and Frisian historical tradition, the trading centre of Dorestad declined after Viking raids from 834 to 863; however, since no convincing Viking archaeological evidence has been found at the site (as of 2007), doubts about this have grown in recent years.[19]

One of the most important Viking families in the Low Countries was that of Rorik of Dorestad (based in Wieringen) and his brother the "younger Harald" (based in Walcheren), both thought to be nephews of Harald Klak.[20] Around 850, Lothair I acknowledged Rorik as ruler of most of Friesland. And again in 870, Rorik was received by Charles the Bald in Nijmegen, to whom he became a vassal. Viking raids continued during that period. Harald's son Rodulf and his men were killed by the people of Oostergo in 873. Rorik died sometime before 882.

Buried Viking treasures consisting mainly of silver have been found in the Low Countries. Two such treasures have been found in Wieringen. A large treasure found in Wieringen in 1996 dates from around 850 and is thought perhaps to have been connected to Rorik. The burial of such a valuable treasure is seen as an indication that there was a permanent settlement in Wieringen.[21]

Around 879, Godfrid arrived in Frisian lands as the head of a large force that terrorised the Low Countries. Using Ghent as his base, they ravaged Ghent, Maastricht, Liège, Stavelot, Prüm, Cologne, and Koblenz. Controlling most of Frisia between 882 and his death in 885, Godfrid became known to history as Godfrid, Duke of Frisia. His lordship over Frisia was acknowledged by Charles the Fat, to whom he became a vassal. Godfried was assassinated in 885, after which Gerolf of Holland assumed lordship and Viking rule of Frisia came to an end.

Viking raids of the Low Countries continued for over a century. Remains of Viking attacks dating from 880 to 890 have been found in Zutphen and Deventer. In 920, King Henry of Germany liberated Utrecht. According to a number of chronicles, the last attacks took place in the first decade of the 11th century and were directed at Tiel and/or Utrecht.[22]

These Viking raids occurred about the same time that French and German lords were fighting for supremacy over the middle empire that included the Netherlands, so their sway over this area was weak. Resistance to the Vikings, if any, came from local nobles, who gained in stature as a result.

References[edit]

- ^ Bazelmans, Jos (2009), "The early-medieval use of ethnic names from classical antiquity: The case of the Frisians", in Derks, Ton; Roymans, Nico (eds.), Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University, pp. 321–337, ISBN 978-90-8964-078-9, archived from the original on 30 August 2017, retrieved 30 August 2017

- ^ Frisii en Frisiaevones, 25–08–02 (Dutch) Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Bertsgeschiedenissite.nl. Retrieved 6 October 2011

- ^ Kortlandt, Frederik (1999). "The origin of the Old English dialects revisited" (PDF). University of Leiden.

- ^ Willemsen, A. (2009), Dorestad. Een wereldstad in de middeleeuwen, Walburg Pers, Zutphen, pp. 23–27, ISBN 978-90-5730-627-3

- ^ a b MacKay, Angus; David Ditchburn (1997). Atlas of Medieval Europe. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-415-01923-1.

- ^ a b Hodges, Richard; David Whitehouse (1983). Mohammed, Charlemagne and the Origins of Europe. Cornell University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8014-9262-4.

dorestad.

- ^ Previté-Orton, Charles, The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, vol. I, pp. 51–52, 151

- ^ a b c d e Milis, L.J.R., "A Long Beginning: The Low Countries Through the Tenth Century" in J.C.H. Blom & E. Lamberts History of the Low Countries, pp. 6–18, Berghahn Books, 1999. ISBN 978-1-84545-272-8.

- ^ a b c d de Vries, Jan W., Roland Willemyns and Peter Burger, Het verhaal van een taal, Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2003, pp. 12, 21–27

- ^ Holmes, U.T and A. H. Schutz (1938), A History of the French Language, p. 29, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, ISBN 0-8196-0191-8

- ^ Beyen, Marnix, "A Tribal Trinity: the Rise and Fall of the Franks, the Frisians and the Saxons in the Historical Consciousness of the Netherlands since 1850" in European History Quarterly 2000 30(4):493–532. ISSN 0265-6914 Fulltext: EBSCO

- ^ Blok, D.P. (1974), De Franken in Nederland, Bussum: Unieboek, 1974, pp. 36–38 on the uncertain identity of the Frisians in early Frankish sources; pp. 54–55 on the problems concerning "Saxon" as a tribal name.

- ^ van Eijnatten, J. and F. van Lieburg, Nederlandse religiegeschiedenis (Hilversum, 2006), pp. 42–43, on the uncertain identity of the "Frisians" in early Frankish sources.

- ^ de Nijs, T, E. Beukers and J. Bazelmans, Geschiedenis van Holland (Hilversum, 2003), pp. 31–33 on the fluctuating character of tribal and ethnic distinctions for the early Medieval period.

- ^ Blok (1974), pp. 117 ff.; de Nijs et al. (2003), pp. 30–33

- ^ Such as Old Saxon, Old English and Old Frisian

- ^ van der Wal, M., Geschiedenis van het Nederlands, 1992 [full citation needed], p. [page needed]

- ^ "Charlemagne: Court and administration". Encyclopædia Britannica. ("Charlemagne relied on his palatium, a shifting assemblage of family members, trusted lay and ecclesiastical companions, and assorted hangers-on, which constituted an itinerant court following the king as he carried out his military campaigns and sought to take advantage of the income from widely scattered royal estates.")

- ^ More info about Viking raids can be found online at L. van der Tuuk, Gjallar. Noormannen in de Lage Landen

- ^ Baldwin, Stephen, "Danish Haralds in 9th Century Frisia". Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "Vikingschat van Wieringen" Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Museumkennis.nl. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ Jesch, Judith, Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse, Boydell & Brewer, 2001. ISBN 978-0-85115-826-6. p. 82.