User:MichielVandaele/sandbox

Cuba[edit]

Republic of Cuba República de Cuba (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Patria o Muerte (in Spanish) "Homeland or Death"[1] | |

| Anthem: La Bayamesa ("The Bayamo Song")[2] | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Havana 23°8′N 82°23′W / 23.133°N 82.383°W |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Ethnic groups | 65.05% White (Spanish, others), 10.08% African, 23.84% Mulatto and Mestizo[3][failed verification] |

| Demonym(s) | Cuban |

| Government | Unitary republic, communist state[4] |

| Raúl Castro | |

• First Vice President | J. R. M. Ventura |

| Raúl Castro | |

• President of the National Assembly | Ricardo Alarcón |

| Independence from Spain/U.S. | |

• Declared | October 10, 1868 from |

• Republic declared | May 20, 1902 from the United States |

| January 1, 1959 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 109,886 km2 (42,427 sq mi) (105th) |

• Water (%) | negligible[5] |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 11,239,363[5] (75th) |

• 2002 census | 11,177,743[5] |

• Density | 102/km2 (264.2/sq mi) (103rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2009 estimate |

• Total | $111.1 billion[6] (62nd) |

• Per capita | $9,700 (86th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2009 estimate |

• Total | $67.26 billion[5] (62nd) |

• Per capita | $5,984 (78th) |

| HDI (2007) | 0.863[7] Error: Invalid HDI value (51st) |

| Currency | Cuban peso(CUP)Cuban convertible peso[8] (CUC) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 |

• Summer (DST) | UTC-4 ((March 11 to November 4)) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +53 |

| ISO 3166 code | CU |

| Internet TLD | .cu |

The Republic of Cuba (English pronunciation: /'kju?b?/; Spanish: República de Cuba, pronounced [re'pußlika ðe 'kußa] ⓘ) is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city.[9][10] To the north of Cuba lies the United States and the Bahamas, Mexico is to the west, the Cayman Islands and Jamaica are to the south, and Haiti and the Dominican Republic are to the southeast.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus found and claimed the island now occupied by Cuba, for the Kingdom of Spain. Cuba remained a territory of Spain until the Spanish–American War ended in 1898, and gained formal independence from the U.S. in 1902. Between 1953 and 1959 the Cuban Revolution occurred, removing the dictatorship[11] of Fulgencio Batista. A new government led by Fidel Castro was later setup. The current Cuban government is considered by the 2010 Democracy Index as "authoritarian".

Cuba is home to over 11 million people and is the most populous island nation in the Caribbean, as well as the largest by area. Its people, culture, and customs draw from diverse sources, such as the aboriginal Taíno and Ciboney peoples, the period of Spanish colonialism, the introduction of African slaves and its proximity to the United States.

Cuba has a 99.8% literacy rate,[12][13] an infant death rate lower than some developed countries,[14] and an average life expectancy of 77.64.[12] In 2006, Cuba was the only nation in the world which met the WWF's definition of sustainable development; having an ecological footprint of less than 1.8 hectares per capita and a Human Development Index of over 0.8 for 2007.[15]

Etymology[edit]

The name Cuba comes from the Taíno language. The exact meaning of the name is unclear but it may be translated either as where fertile land is abundant (cubao),[16] or great place (coabana).[17] Scholars who believe that Christopher Columbus was Portuguese state that Cuba was named by Columbus for the ancient town of Cuba in the district of Beja in Portugal.[18][19]

History[edit]

Pre-Columbian era[edit]

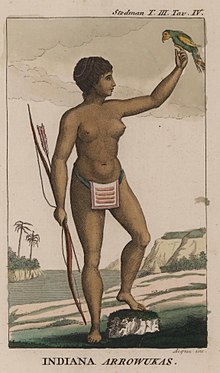

Cuba was inhabited by Native American people known as the Taíno, also called Arawak by the Spanish, and Guanajatabey and Ciboney people before the arrival of the Spanish. The ancestors of these Native Americans migrated from the mainland of North, Central and South America several centuries earlier.[20] The native Tainos called the island Caobana.[21] The Taíno were farmers and the Ciboney were farmers, fishers and hunter-gatherers.

Spanish colonization[edit]

After first landing on an island then called Guanahani on October 12, 1492,[22] Christopher Columbus landed on Cuba's northeastern coast near what is now Baracoa on October 27[22] or 28.[23][24] He claimed the island for the new Kingdom of Spain[25] and named Isla Juana after Juan, Prince of Asturias.[26] In 1511, the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at Baracoa; other towns soon followed including the future capital of San Cristobal de la Habana which was founded in 1515. The Spanish enslaved the approximately 100,000 indigenous people who resisted conversion to Christianity,[citation needed] setting them primarily to the task of searching for gold. Within a century the indigenous people were virtually wiped out due to multiple factors, including Eurasian infectious diseases aggravated in large part by a lack of natural resistance as well as privation stemming from repressive colonial subjugation.[27] In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox.[28][29]

Cuba remained a Spanish possession for almost 400 years (1511–1898), with an economy based on plantation agriculture, mining, and the export of sugar, coffee, and tobacco to Europe and later to North America. The work was done primarily by African slaves brought to the island.

The small land-owning elite of Spanish settlers held social and economic powers supported by a population of Spaniards born on the island (Criollos), other Europeans, and African-descended slaves. The population in 1817 was 630,980, of which 291,021 were white, 115,691 free black, and 224,268 black slaves.[30]

Independence wars[edit]

In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in Latin America rebelled and formed independent states, Cuba remained loyal. Although there was agitation for independence, the Spanish Crown gave Cuba the motto La Siempre Fidelísima Isla ("The Always Most Faithful Island"). This loyalty was due partly to Cuban settlers' dependence on Spain for trade, their desire for protection from pirates and against a slave rebellion, and partly because they feared the rising power of the United States more than they disliked Spanish rule.[citation needed]

Ten Years' War[edit]

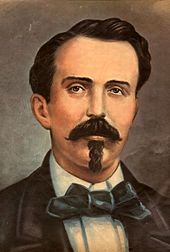

Independence from Spain was the motive for a rebellion in 1868 led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. De Céspedes, a sugar planter, freed his slaves to fight with him for a free Cuba. On 27 December 1868, he issued a decree condemning slavery in theory but accepting it in practice and declaring free any slaves whose masters present them for military service.[31] The 1868 rebellion resulted in a prolonged conflict known as the Ten Years' War. The United States declined to recognize the new Cuban government, although many European and Latin American nations did so.[32] In 1878, the Pact of Zanjón ended the conflict, with Spain promising greater autonomy to Cuba. In 1879–1880, Cuban patriot Calixto García attempted to start another war known as the Little War but received little support.[33]

Period between wars[edit]

In Cuba, a sophisticated and prosperous sugar industry had employed chattel slavery until the final third of the 19th century. Cuba produced 720,250 metric tons of sugar 1n 1868, more than forty percent of cane sugar reaching the world market that year. Slavery had been maintained in Cuba, however, while abolition was underway elsewhere. Abolition in Cuba began the final third of the 19th century, and was completed in the 1880s.[34][35]

War of 1895[edit]

An exiled dissident named José Martí founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York in 1892. The aim of the party was to achieve Cuban independence from Spain.[36] In January 1895 Martí traveled to Montecristi and Santo Domingo to join the efforts of Máximo Gómez.[36] Martí recorded his political views in the Manifesto of Montecristi.[37] Fighting against the Spanish army began in Cuba on 24 February 1895, but Martí was unable to reach Cuba until 11 April 1895.[36] Martí was killed in the battle of Dos Rios on 19 May 1895.[36] His death immortalized him as Cuba's national hero.[37]

Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army which relied mostly on guerrilla and sabotage tactics. The Spaniards began a campaign of suppression. General Valeriano Weyler, military governor of Cuba, herded the rural population into what he called reconcentrados, described by international observers as "fortified towns". These are often considered the prototype for 20th-century concentration camps.[38] Between 200,000 and 400,000 Cuban civilians died from starvation and disease in the camps, numbers verified by the Red Cross and United States Senator and former Secretary of War Redfield Proctor. American and European protests against Spanish conduct on the island followed.[39]

Spanish–American War[edit]

USS Maine[edit]

The U.S. battleship Maine arrived in Havana on 25 January 1898 to offer protection to the 8,000 American residents on the island, but the Spanish saw this as intimidation. On the evening of 15 February 1898, the Maine blew up in the harbor, killing 252 crew. Another eight crew members died of their wounds in hospital over the next few days.[40] A Naval Board of Inquiry headed by Captain William T. Sampson was appointed to investigate the cause of the explosion on the Maine. Having examined the wreck and taken testimony from eyewitnesses and experts, the board reported on 21 March 1898 that the Maine had been destroyed by "a double magazine set off from the exterior of the ship, which could only have been produced by a mine."[40]

The facts remain disputed today, although an investigation by Admiral Hyman G. Rickover in 1976 established that the blast was most likely a large internal explosion. Rickover believes the explosion was caused by a spontaneous combustion in inadequately ventilated bituminous coal which ignited gunpowder in an adjacent magazine.[41][42] The original 1898 board was unable to fix the responsibility for the disaster, but a furious American populace, fueled by an active press— notably the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst— concluded that the Spanish were to blame and demanded action.[40] The U.S. Congress passed a resolution calling for intervention, and President William McKinley complied.[43] Spain and the United States declared war on each other in late April.

Early 20th century[edit]

After the Spanish-American War, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1898), by which Spain ceded Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States for the sum of $20 million.[44] Under the same treaty, Spain relinquished all claim of sovereignty over Cuba. Theodore Roosevelt, who had fought in the Spanish-American War and had some sympathies with the independence movement, succeeded McKinley as U.S. President in 1901 and abandoned the treaty. Cuba gained formal independence from the U.S. on May 20, 1902, as the Republic of Cuba. Under Cuba's new constitution, the U.S. retained the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and to supervise its finances and foreign relations. Under the Platt Amendment, the U.S. leased the Guantánamo Bay naval base from Cuba.

Following disputed elections in 1906, the first president, Tomás Estrada Palma, faced an armed revolt by independence war veterans who defeated the meager government forces.[45] The U.S. intervened by occupying Cuba and named Charles Edward Magoon as Governor for three years. Cuban historians have attributed Magoon's governorship as having introduced political and social corruption.[46] In 1908, self-government was restored when José Miguel Gómez was elected President, but the U.S. continued intervening in Cuban affairs. In 1912, the Partido Independiente de Color attempted to establish a separate black republic in Oriente Province,[47] but was suppressed by General Monteagudo with considerable bloodshed.

During World War I, Cuba exported considerable quantities of sugar to Britain. Cuba was able to avoid U-boat attacks by the subterfuge of shipping the sugar to Sweden. The Menocal government declared war on Germany very soon after the United States.

A constitutional government was maintained until 1930 when Gerardo Machado y Morales suspended the constitution. During Machado's tenure, a nationalistic economic program was pursued with several major national development projects which included the Carretera Central and El Capitolio. Machado's hold on power was weakened following a decline in demand for exported agricultural produce due to the Great Depression, attacks by independence war veterans, and attacks by covert terrorist organizations, principally the ABC.[citation needed]

During a general strike in which the Communist Party sided with Machado,[48] the senior elements of the Cuban army forced Machado into exile. The Party then installed Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada, son of Cuba's founding father (Carlos Manuel de Céspedes), as President. During 4–5 September 1933, a second coup overthrew Céspedes which led to the formation of the first Ramón Grau government. Notable events in this violent period include the separate sieges of Hotel Nacional de Cuba and Atares Castle. This government lasted 100 days but engineered radical socialist changes in Cuban society, including the abolishment of the Platt Amendment and instating of womens' suffrage in Cuba. In 1934, Grau was ousted in favor of Carlos Mendieta, the first in a series of puppet presidents subordinate to the army and its young chief of staff, Fulgencio Batista.

Fulgencio Batista was democratically elected President in the elections of 1940, so far the only non-white Cuban endorsed for the nation's highest office.[49][50][51] His government carried out major social reforms. Several members of the Communist Party held office under his administration[52] and established numerous economic regulations and pro-union policies, as well as the Cuban Constitution of 1940, which engineered radical progressive ideas.[53] Batista's administration formally took Cuba to the Allies of World War II camp in World War II. Cuba declared war on Japan on December 9, 1941, then on Germany and Italy on December 11, 1941. Cuban armed forces were not greatly involved in combat during World War II, although president Batista suggested a joint U.S.-Latin American assault on Francoist Spain in order to overthrow its authoritarian regime.[54]

Ramón Grau, who lost in 1940 to Batista, finally returned in the 1944 elections by defeating Batista's preferred successor, Carlos Saladrigas Zayas. In 1948, his Revolutionary Authentic Party won again when Carlos Prío Socarrás won, the last person elected to the presidency by free and fair elections. The two terms of the Authenic Party saw an influx of investment fueled a boom which raised living standards for all segments of society and created a prosperous middle class in most urban areas. The gap between rich and poor became wider and more obvious.[55]

The 1952 election was a three-way race. Roberto Agramonte of the Ortodoxos party led in all the polls, followed by Dr. Aurelio Hevia of the Auténtico party, and Fulgencio Batista, seeking a return to office, as a distant third. Both Agramonte and Hevia had decided to name Col. Ramón Barquín to head the Cuban armed forces after the elections. Barquín, then a diplomat in Washington, DC, was a top officer. He was respected by the professional army and had promised to eliminate corruption in the ranks. Batista feared that Barquín would oust him and his followers. When it became apparent that Batista had little chance of winning, he staged a coup on 10 March 1952. Batista held on to power with the backing of a nationalist section of the army as a "provisional president" for the next two years.

In March 1952 Justo Carrillo informed Barquín in Washington that the inner circles knew that Batista had plotted the coup. They immediately began to conspire to oust Batista and restore democracy and civilian government in what was later dubbed La Conspiracion de los Puros de 1956 (Agrupacion Montecristi). In 1954, Batista agreed to elections. The Partido Auténtico put forward ex-President Grau as their candidate, but he withdrew amid allegations that Batista was rigging the elections in advance.

| “ | At the beginning of 1959 United States companies owned about 40 percent of the Cuban sugar lands – almost all the cattle ranches – 90 percent of the mines and mineral concessions – 80 percent of the utilities – practically all the oil industry – and supplied two-thirds of Cuba's imports. | ” |

| — U.S. President John F. Kennedy, 1960 [56] | ||

In April 1956 Batista ordered Barquín to become General and chief of the army, but Barquín decided to move forward with his coup to secure total power. On 4 April 1956, a coup by hundreds of career officers led by Barquín was frustrated by Rios Morejon. The coup broke the back of the Cuban armed forces. The officers were sentenced to the maximum terms allowed by Cuban Martial Law. Barquín was sentenced to solitary confinement for eight years. La Conspiración de los Puros resulted in the imprisonment of the commanders of the armed forces and the closing of the military academies.

Cuba had Latin America's highest per capita consumption rates of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones and radios, though this consumption was largely by the small elite class and foreigners.[57] In 1958, Cuba was a relatively well-advanced country by Latin American standards, and in some cases by world standards.[58] Cuba attracted more immigrants, primarily from Europe, as a percentage of population than the U.S. The United Nations noted Cuba for its large middle class.[citation needed] On the other hand, Cuba was affected by perhaps the largest labor union privileges in Latin America, including bans on dismissals and mechanization. They were obtained in large measure "at the cost of the unemployed and the peasants", leading to disparities.[59]

Between 1933 and 1958, Cuba extended economic regulations enormously, causing economic problems.[51][60] Unemployment became a problem as graduates entering the workforce could not find jobs.[51] The middle class, which was comparable to the United States, became increasingly dissatisfied with the unemployment. The labor unions supported Batista until the very end.[49][51]

Revolution[edit]

On 2 December 1956 a party of 82 people on the yacht Granma landed in Cuba. The party, led by Fidel Castro, had the intention of establishing an armed resistance movement in the Sierra Maestra. While facing armed resistance from Castro's rebel fighters in the mountains, Fulgencio Batista's regime was weakened and crippled by a United States arms embargo imposed on 14 March 1958. By late 1958, the rebels broke out of the Sierra Maestra and launched a general popular insurrection. After the fighters captured Santa Clara, Batista fled from Havana on 1 January 1959 to exile in Portugal. Barquín negotiated the symbolic change of command between Camilo Cienfuegos, Che Guevara, Raúl Castro, and his brother Fidel Castro after the Supreme Court decided that the Revolution was the source of law and its representatives should assume command.

Fidel Castro's forces entered the capital on 8 January 1959. Shortly afterward, a liberal lawyer, Dr Manuel Urrutia Lleó became president. He was backed by Castro's 26th of July Movement because they believed his appointment would be welcomed by the United States.[citation needed] Disagreements within the government culminated in Urrutia's resignation in July 1959. He was replaced by Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado, who served as president until 1976. Castro became prime minister in February 1959, succeeding José Miró in that post.

In its first year, the new revolutionary government expropriated private property with little or no compensation, nationalized public utilities, tightened controls on the private sector, and closed down the mafia-controlled gambling industry. The CIA conspired with the Chicago mafia in 1960 and 1961 to assassinate Fidel Castro, according to documents declassified in 2007.[61][62]

Some of these measures were undertaken by Fidel Castro's government in the name of the program outlined in the Manifesto of the Sierra Maestra.[63] The government nationalized private property totaling about USD $25 billion,[64] of which American property made up around USD $1 billion.[64][65]

By the end of 1960, the coletilla made its appearance, and most newspapers in Cuba had been expropriated, taken over by the unions, or had been abandoned.[57][66] All radio and television stations were in state control.[57] Moderate teachers and professors were purged.[57] In any year, about 20,000 dissenters were imprisoned.[57] Some homosexuals, religious practitioners, and others were sent to labor camps where they were subject to political "re-education".[67] One estimate is that 15,000 to 17,000 people were executed.[68]

The Communist Party strengthened its one-party rule, with Castro as ultimate leader.[57] Fidel's brother, Raúl Castro, became the army chief.[57] Loyalty to Castro became the primary criterion for all appointments.[69] In September 1960, the revolutionary government created a system known as Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), which provided neighborhood spying.[57]

In the 1961 New Year's Day parade, the administration exhibited Soviet tanks and other weapons.[69] Eventually, Cuba built up the second largest armed forces in Latin America, second only to Brazil.[70] Cuba became a privileged client-state of the Soviet Union.[71]

By 1961, hundreds of thousands of Cubans had left for the United States.[72] The 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion (La Batalla de Girón) was an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the Cuban government by a U.S.-trained force of Cuban exiles with U.S. military support. The plan was launched in April 1961, less than three months after John F. Kennedy became the U.S. President. The Cuban armed forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the exiles in three days. Cuban-American relations were exacerbated the following year by the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the Kennedy administration demanded the immediate withdrawal of Soviet missiles placed in Cuba placed in response to U.S. nuclear missiles in Turkey and the Middle East. The Soviets and Americans soon came to an agreement. The Soviets would remove Soviet missiles from Cuba and the Americans would remove missiles from Turkey and the Middle East. Kennedy also agreed not to invade Cuba in the future. Cuban exiles captured during the Bay of Pigs Invasion were exchanged for a shipment of supplies from America.[49]

By 1963, Cuba was moving towards a full-fledged Communist system modeled on the USSR.[73] The U.S. imposed a complete diplomatic and commercial embargo on Cuba and began Operation Mongoose, a program of covert CIA operations.

In 1965, Castro merged his revolutionary organizations with the Communist Party, of which he became First Secretary; Blas Roca was named Second Secretary. Roca was succeeded by Raúl Castro, who, as Defense Minister and Fidel's closest confidant, became and remained the second most powerful figure in Cuba until his brother's retirement. Raúl's position was strengthened by the departure of Che Guevara to launch unsuccessful insurrections in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and then Bolivia, where he was killed in 1967.

During the 1970s, Fidel Castro dispatched tens of thousands troops in support of Soviet-supported wars in Africa, particularly the MPLA in Angola and Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia.[74]

The standard of living in 1970s was "extremely spartan" and discontent was rife.[75] Fidel Castro admitted the failures of economic policies in a 1970 speech.[75] By the mid-1970s, Castro started economic reforms.

Cuba was suspended from the Organization of American States (OAS) in 1962 in support of the U.S. embargo, but in 1975 the OAS lifted all sanctions against Cuba, with approval of 16 countries, including the U.S.[76]

On 3 June 2009[dubious ], the OAS adopted a resolution to end the 47-year exclusion of Cuba. The meetings were contentious, with the U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton walking out at one point. However, in the end, the U.S. delegation agreed with the other members and approved the resolution. Cuban leaders have repeatedly announced they are not interested in rejoining the OAS.[77]

Recent affairs[edit]

As of 2002, some 1.2 million persons of Cuban background (about 10% of the current population of Cuba) reside in the U.S.[78][79] Many of them left the island for the United States, often by sea in small boats and fragile rafts. On 6 April 1980, 10,000 Cubans stormed the Peruvian embassy in Havana seeking political asylum. The following day, the Cuban government granted permission for the emigration of Cubans seeking refuge in the Peruvian embassy.[citation needed] On 16 April, 500 Cubans left the Peruvian Embassy for Costa Rica. On 21 April, many of those Cubans started arriving in Miami via private boats and were halted by[clarification needed] the U.S. State Department, but the emigration continued, because Castro allowed anyone who desired to leave the country to do so through the port of Mariel. Over 125,000 Cubans emigrated to the U.S. before the flow of vessels ended on 15 June.[citation needed]

Castro's rule was severely tested in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse (known in Cuba as the Special Period), with effects such as food shortages.[80][81] The government did not accept American donations of food, medicines, and cash until 1993.[80] On 5 August 1994, state security dispersed protesters in a spontaneous protest in Havana.[82]

Cuba has found a new source of aid and support in the People's Republic of China, and new allies in Hugo Chávez, President of Venezuela and Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, both major oil and gas exporters. In 2003, the government arrested and imprisoned a large number of civil activists, a period known as the "Black Spring".[83][84]

On July 31, 2006, Fidel Castro temporarily delegated his major duties to his brother, First Vice President, Raúl Castro, while Fidel recovered from surgery for an "acute intestinal crisis with sustained bleeding".[citation needed] On 2 December 2006, Fidel was too ill to attend the 50th anniversary commemoration of the Granma boat landing, fuelling speculation that he had stomach cancer,[85] although there was evidence his illness was a digestive problem and not terminal.[86]

In January 2007, footage was released of Fidel Castro meeting Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, in which Castro "appeared frail but stronger than three months ago".[87] In February 2008, Fidel Castro announced his resignation as President of Cuba,[88] and on 24 February Raúl was elected as the new President.[89] In his acceptance speech, Raúl promised that some of the restrictions that limit Cubans' daily lives would be removed.[90] In March 2009, Raúl Castro removed some of Fidel Castro's officials.[91]

Human rights[edit]

The Cuban government has been accused of numerous human rights abuses including torture, arbitrary imprisonment, unfair trials, and extrajudicial executions (also known as "El Paredón").[92][93] The Human Rights Watch alleges that the government "represses nearly all forms of political dissent" and that "Cubans are systematically denied basic rights to free expression, association, assembly, privacy, movement, and due process of law".[94]

Cuba had the second-highest number of imprisoned journalists of any nation in 2008 (the People's Republic of China had the highest) according to various sources, including the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), an international NGO, and Human Rights Watch.[95][96] As a result of ownership restrictions, computer ownership rates are among the world's lowest.[97] The right to use the Internet is granted only to selected locations and they may be monitored.[97][98] Connecting to the Internet illegally can lead to a five-year prison sentence.[citation needed]

Cuban dissidents who commit crimes face arrest and imprisonment. In the 1990s, Human Rights Watch reported that Cuba's extensive prison system, one of the largest in Latin America, consists of some 40 maximum-security prisons, 30 minimum-security prisons, and over 200 work camps.[99] According to Human Rights Watch, political prisoners, along with the rest of Cuba's prison population, are confined to jails with substandard and unhealthy conditions.[99]

Citizens cannot leave or return to Cuba without first obtaining official permission in addition to their passport and the visa requirements of their destination.[94]

Economy[edit]

The Cuban state adheres to socialist principles in organizing its largely state-controlled planned economy. Most of the means of production are owned and run by the government and most of the labor force is employed by the state. Recent years have seen a trend towards more private sector employment. By 2006, public sector employment was 78% and private sector 22%, compared to 91.8% to 8.2% in 1981.[100] Capital investment is restricted and requires approval by the government. The Cuban government sets most prices and rations goods. Any firm wishing to hire a Cuban must pay the Cuban government, which in turn will pay the employee in Cuban pesos.[101] Cubans can not change jobs without government permission.[51] The average wage at the end of 2005 was 334 regular pesos per month ($16.70 per month) and the average pension was $9 per month.[102]

Cuba relied heavily on trade with the Soviet Union. From the late 1980s, Soviet subsidies for Cuban goods started to dry up. Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba depended on Moscow for substantial aid and sheltered markets for its exports. The removal of these subsidies sent the Cuban economy into a rapid depression known in Cuba as the Special Period. In 1992 the United States tightened the trade embargo, hoping to see democratisation of the sort that took place in Eastern Europe.

Like some other Communist and post-Communist states following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba took limited free market-oriented measures to alleviate severe shortages of food, consumer goods, and services. These steps included allowing some self-employment in certain retail and light manufacturing sectors, the legalization of the use of the US dollar in business, and the encouragement of tourism. Cuba has developed a unique urban farm system (the organopónicos) to compensate for the end of food imports from the Soviet Union. In recent years, Cuba has rolled back some of the market oriented measures undertaken in the 1990s. In 2004 Cuban officials publicly backed the Euro as a "global counter-balance to the US dollar", and eliminated U.S. currency from circulation in its stores and businesses.[citation needed]

Tourism was initially restricted to enclave resorts where tourists would be segregated from Cuban society, referred to as "enclave tourism" and "tourism apartheid".[103] Contacts between foreign visitors and ordinary Cubans were de facto illegal until 1997.[104] In 1996 tourism surpassed the sugar industry as the largest source of hard currency for Cuba. Cuba has tripled its market share of Caribbean tourism in the last decade; as a result of significant investment in tourism infrastructure, this growth rate is predicted to continue.[105] 1.9 million tourists visited Cuba in 2003, predominantly from Canada and the European Union, generating revenue of $2.1 billion.[106] The rapid growth of tourism during the Special Period had widespread social and economic repercussions in Cuba, and led to speculation about the emergence of a two-tier economy.[107] The Medical tourism sector caters to thousands of European, Latin American, Canadian, and American consumers every year.

The communist agricultural production system was ridiculed by Raúl Castro in 2008.[108] Cuba now imports up to 80% of food used for rations.[108] Before 1959, Cuba boasted as many cattle as people.

For some time, Cuba has been experiencing a housing shortage because of the state's failure to keep pace with increasing demand.[109] The government instituted food rationing policies in 1962, which were exacerbated following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the tightening of the U.S. embargo. Studies have shown that, as late as 2001, the average Cuban's standard of living was lower than before the downturn of the post-Soviet period. Paramount issues have been state salaries failing to meet personal needs under the state rationing system, chronically plagued with shortages. The variety and quantity of available rationed goods declined.

Under Venezuela's Mission Barrio Adentro, Hugo Chávez has supplied Cuba with up to 80,000 barrels (13,000 m3) of oil per day in exchange for 30,000 doctors and teachers.

In 2005 Cuba had exports of $2.4 billion, ranking 114 of 226 world countries, and imports of $6.9 billion, ranking 87 of 226 countries.[110] Its major export partners are China 27.5%, Canada 26.9%, Netherlands 11.1%, Spain 4.7% (2007).[6] Cuba's major exports are sugar, nickel, tobacco, fish, medical products, citrus, and coffee;[6] imports include food, fuel, clothing, and machinery. Cuba presently holds debt in an amount estimated to be $13 billion,[111] approximately 38% of GDP.[112] According to the Heritage Foundation, Cuba is dependent on credit accounts that rotate from country to country.[113] Cuba's prior 35% supply of the world's export market for sugar has declined to 10% due to a variety of factors, including a global sugar commodity price drop that made Cuba less competitive on world markets.[114] At one time, Cuba was the world's most important sugar producer and exporter. As a result of diversification, underinvestment, and natural disasters, Cuba's sugar production has seen a drastic decline. In 2002 more than half of Cuba's sugar mills were shut down. Cuba holds 6.4% of the global market for nickel,[115] which constitutes about 25% of total Cuban exports.[116] A 2005 US Geological Survey report estimates that the North Cuba Basin could contain 4.6 billion barrels of oil and 9.8 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.[117]

In 2010[update], Cubans were allowed to build their own houses. According to Raul Castro, they will be able to improve their houses with this new permission, but the government will not endorse these new houses or improvements.[118]

On August 2, 2011, The New York Times reported Cuba as reaffirming their intent to legalize "buying and selling" of private property before the year ends. According to experts, the private sale of property could "transform Cuba more than any of the economic reforms announced by President Raúl Castro’s government".[119] It will cut more than one million state jobs including party bureaucrats which resist the changes.[120]

Government and politics[edit]

The Constitution of 1976, which defined Cuba as a socialist republic, was replaced by the Constitution of 1992, which is guided by the ideas of José Martí, Marx, Engels and Lenin.[122] The constitution describes the Communist Party of Cuba as the "leading force of society and of the state".[122] The first secretary of the Communist Party is concurrently President of the Council of State (President of Cuba) and President of the Council of Ministers (sometimes referred to as Prime Minister of Cuba).[123] Members of both councils are elected by the National Assembly of People's Power.[122] The President of Cuba, who is also elected by the Assembly, serves for five years and there is no limit to the number of terms of office.[122]

The Supreme Court of Cuba serves as the nation's highest judicial branch of government. It is also the court of last resort for all appeals against the decisions of provincial courts.

Cuba's national legislature, the National Assembly of People's Power (Asamblea Nacional de Poder Popular), is the supreme organ of power; 609 members serve five-year terms.[122] The assembly meets twice a year; between sessions legislative power is held by the 31 member Council of Ministers. Candidates for the Assembly are approved by public referendum. All Cuban citizens over 16 who have not been convicted of a criminal offense can vote. Article 131 of the Constitution states that voting shall be "through free, equal and secret vote".[122] Article 136 states: "In order for deputies or delegates to be considered elected they must get more than half the number of valid votes cast in the electoral districts".[122] Votes are cast by secret ballot and counted in public view. Nominees are chosen at local gatherings from multiple candidates before gaining approval from election committees. In the subsequent election, there is only one candidate for each seat, who must gain a majority to be elected.

No political party is permitted to nominate candidates or campaign on the island, though the Communist Party of Cuba has held five party congress meetings since 1975. In 1997 the party claimed 780,000 members, and representatives generally constitute at least half of the Councils of state and the National Assembly. The remaining positions are filled by candidates nominally without party affiliation. Other political parties campaign and raise finances internationally, while activity within Cuba by opposition groups is minimal and illegal.

The country is subdivided into 15 provinces and one special municipality (Isla de la Juventud). These were formerly part of six larger historical provinces: Pinar del Río, Habana, Matanzas, Las Villas, Camagüey and Oriente. The present subdivisions closely resemble those of the Spanish military provinces during the Cuban Wars of Independence, when the most troublesome areas were subdivided. The provinces are divided into municipalities.

|

Military[edit]

Cuba devoted 9–13% of its GDP to military expenditures.[124] Castro built up the second largest armed forces in Latin America; only Brazil's were larger.[70] From 1975 until the late 1980s, Soviet military assistance enabled Cuba to upgrade its military capabilities. Since the loss of Soviet subsidies Cuba has scaled down the numbers of military personnel, from 235,000 in 1994 to about 60,000 in 2003.[125] Cuba is secretive about its military spending.[124]

Foreign relations[edit]

From its inception, the Cuban Revolution defined itself as internationalist, joining Comecon in 1972. Cuba was a major contributor to Soviet-supported wars in Africa, Central America and Asia. In Africa, the largest war was in Angola, where Cuba sent tens of thousands of troops. Cuba was a friend of the Ethiopian leader Mengistu Haile Mariam.[126] In Africa, Cuba supported 17 leftist governments. In some countries it suffered setbacks, such as in eastern Zaire, but in others Cuba had significant success. Major engagements took place in Algeria, Zaire, Yemen,[127] Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique.

The Cuban government's military involvement in Latin America—mostly with the aim of overthrowing U.S. backed right wing regimes, many of them dictatorial—has been extensive. One of the earliest interventions was the Marxist militia led by Che Guevara in Bolivia in 1967, though a modicum of funds and troops were sent. Lesser known actions include the 1959 missions to the Dominican Republic[128] and Panama.[citation needed] In the former, the Cuban government provided military assistance to a group of Dominican exiles with the intention of overthrowing the tyrannical dictator Rafael Trujillo. Although the expedition failed and most of its members were murdered by the government, today they are recognized as heroes and a prominent monument was erected in their memory in Santo Domingo by the Dominican government. The Museo Memorial de la Resistencia Dominicana ("Memorial Museum of the Dominican Resistance,") where the heroes of 1959 feature prominently, is being built by the Dominican Government.[129] The socialist government in Nicaragua was openly supported by Cuba and can be considered its greatest success in Latin America.[citation needed] Cuba is a founding member of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas. More than 30,000 Cuban doctors currently work abroad, in countries such as Venezuela and Zimbabwe.[130] The membership of Cuba in the United Nations Human Rights Council has received criticism.[131]

The European Union in 2003 accused the Cuban government of "continuing flagrant violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms".[132] In 2008, the EU and Cuba agreed to resume full relations and cooperation activities.[133] The United States continues an embargo against Cuba "so long as it continues to refuse to move toward democratization and greater respect for human rights".[134] United States President Barack Obama stated on April 17, 2009, in Trinidad and Tobago that "the United States seeks a new beginning with Cuba",[135] and reversed the Bush Administration's prohibition on travel and remittances by Cuban-Americans from the United States to Cuba.[136]

Geography[edit]

Cuba is an archipelago of islands located in the northern Caribbean Sea at the confluence with the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. It lies between latitudes 19° and 24°N, and longitudes 74° and 85°W. The United States lies to the north-west, the Bahamas to the north, Haiti to the east, Jamaica and the Cayman Islands to the south, and Mexico to the west. Cuba is the principal island, surrounded by four smaller groups of islands: the Colorados Archipelago on the northwestern coast, the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago on the north-central Atlantic coast, the Jardines de la Reina on the south-central coast and the Canarreos Archipelago on the southwestern coast.

The main island is 1,199 km (745 mi) long, constituting most of the nation's land area (105,006 km2 (40,543 sq mi)) and is the largest island in the Caribbean and 16th-largest island in the world by land area. The main island consists mostly of flat to rolling plains apart from the Sierra Maestra mountains in the southeast, whose highest point is Pico Turquino (1,975 m (6,480 ft)). The second-largest island is Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth) in the Canarreos archipelago, with an area of 3,056 km2 (1,180 sq mi). Cuba has a total land area of 110,860 km2 (42,803 sq mi).

Climate[edit]

The local climate is tropical, moderated by northeasterly trade winds that blow year-round. In general (with local variations), there is a drier season from November to April, and a rainier season from May to October. The average temperature is 21 °C (69.8 °F) in January and 27 °C (80.6 °F) in July. The warm temperatures of the Caribbean Sea and the fact that Cuba sits across the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico combine to make the country prone to frequent hurricanes. These are most common in September and October.

Resources[edit]

The most important mineral resource is nickel, of which Cuba has the world's second largest reserves (after Russia).[137] Sherritt International of Canada operates a large nickel mining facility in Moa. Cuba is the world's fifth-largest producer of refined cobalt, a byproduct of nickel mining operations.[137] Recent oil exploration has revealed that the North Cuba Basin could produce approximately 4.6 billion barrels (730,000,000 m3) to 9.3 billion barrels (1.48×109 m3) of oil. In 2006, Cuba started to test-drill these locations for possible exploitation.[138]

Demographics[edit]

| Official 1899–2002 Cuba Census[3][139][140] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race % | 1899 | 1907 | 1919 | 1931 | 1943 | 1953 | 1981 | 2002 |

| White | 66.9 | 69.7 | 72.2 | 72.1 | 74.3 | 72.8 | 66.0 | 65.05 |

| Black | 14.9 | 13.4 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 9.7 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 10.08 |

| Mulatto | 17.2 | 16.3 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 15.6 | 14.5 | 21.9 | 24.86 |

| Asian | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | ? |

Immigration to Cuba[edit]

Between 1882 and 1898, a total of 508,455 people left Spain, and more than 750,000 Spanish immigrants left for Cuba between 1899 and 1923, with many returning to Spain.[141]

Current demographics[edit]

According to the census of 2002, the population was 11,177,743,[3] including 5,597,233 men and 5,580,510 women. The racial make-up was 7,271,926 whites, 1,126,894 blacks and 2,778,923 mulattoes (or mestizos).[142] The population of Cuba has very complex origins and intermarriage between diverse groups is general. There is disagreement about racial statistics. The Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami says that 62% is black,[143] whereas statistics from the Cuban census state that 65.05% of the population was white in 2002. The Minority Rights Group International says that "An objective assessment of the situation of Afro-Cubans remains problematic due to scant records and a paucity of systematic studies both pre- and post-revolution. Estimates of the percentage of people of African descent in the Cuban population vary enormously, ranging from 33.9 per cent to 62 per cent".[144]

Immigration and emigration have played a prominent part in the demographic profile of Cuba during the 20th century. During the 18th, 19th, and the early part of the 20th century large waves of Canarian, Catalan, Andalusian, Galician, and other Spanish people immigrated to Cuba. Between 1900 and 1930 close to a million Spaniards arrived from Spain. Other foreign immigrants include: French,[145] Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Dutch, Greek, British, Irish, and other ethnic groups, including a small number of descendants of U.S. citizens who arrived in Cuba in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Cuba has a sizable number of Asian people who comprise 1% of the population. They are primarily of Chinese descent (see Chinese Cubans), followed by Filipino, Koreans and Vietnamese people. They are descendants of farm laborers brought to the island by Spanish and American contractors during the 19th and early 20th century.[citation needed] Afro-Cubans are descended primarily from the Kongo people.[citation needed], as well as several thousand North African refugees, most notably the Sahrawi Arabs of Western Sahara under Moroccan occupation since 1976.[146]

Cuba's birth rate (9.88 births per thousand population in 2006)[147] is one of the lowest in the Western Hemisphere. Its overall population increased continuously from around 7 million in 1961 to over 11 million now, but the increase has stopped in the last few decades, and a decrease began in 2006, with a fertility rate of 1.43 children per woman.[148] This drop in fertility is among the largest in the Western Hemisphere.[149] Cuba has unrestricted access to legal abortion and an abortion rate of 58.6 per 1000 pregnancies in 1996, compared to an average of 35 in the Caribbean, 27 in Latin America overall, and 48 in Europe. Contraceptive use is estimated at 79% (in the upper third of countries in the Western Hemisphere).[150]

Cuba is officially a secular state. After having long maintained that churches were fronts for subversive political activity, the government reversed course in 1992, amending the constitution to characterize the state as secular instead of atheist.[citation needed] It has many faiths representing the widely varying culture. Roman Catholicism was the largest religion; it was brought to the island by the Spanish and remains the dominant faith,[113] with 11 dioceses, 56 orders of nuns, and 24 orders of priests. In January 1998, Pope John Paul II paid a historic visit to the island, invited by the Cuban government and Catholic Church. The religious landscape of Cuba is also strongly marked by syncretisms of various kinds. Catholicism is often practiced in tandem with Santería, a mixture of Catholicism and other, mainly African, faiths that include a number of cults. La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre (the Virgin of Cobre) is the Catholic patroness of Cuba, and a symbol of Cuban culture. In Santería, she has been syncretized with the goddess Oshun.

| Official Cuban migration to the U.S.[139][140] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Immigration |

White | Black | Other | Asian | Number |

| 1959–64 | 93.3 | 1.2 | 5.3 | 0.2 | 144,732 |

| 1965–74 | 87.7 | 2.0 | 9.1 | 0.2 | 247,726 |

| 1975–79 | 82.6 | 4.0 | 13.3 | 0.1 | 29,508 |

| 1980 | 80.9 | 5.3 | 13.7 | 0.1 | 94,095 |

| 1981–89 | 85.7 | 3.1 | 10.9 | 0.3 | 77,835 |

| 1990–93 | 84.7 | 3.2 | 11.9 | 0.2 | 60,244 |

| 1994–2000 | 85.8 | 3.7 | 10.4 | 0.7 | 174,437 |

| Total | 87.2 | 2.9 | 10.7 | 0.2 | 828,577 |

Three hundred thousand Cubans belong to the island's 54 Protestant denominations. Pentecostalism has grown rapidly in recent years, and the Assemblies of God alone claims a membership of over 100,000 people. Cuba has small communities of Jews, Muslims and members of the Bahá'í Faith.[151] Most Jewish Cubans are descendants of Polish and Russian Ashkenazi Jews who fled pogroms at the beginning of the 20th century. There is a sizeable number of Sephardic Jews in Cuba who trace their origin to Turkey. Most of these Sephardic Jews live in the provinces, although they maintain a synagogue in Havana.

Cuban migration[edit]

In the last half-century, several hundred thousand Cubans of all social classes have emigrated to the United States,[152] Spain, the United Kingdom, Canada, Mexico, and other countries. On 9 September 1994, the U.S. and Cuban governments agreed that the U.S. would grant at least 20,000 visas annually in exchange for Cuba's pledge to prevent further unlawful departures on boats.[153]

Languages[edit]

The official language of Cuba is Spanish and the vast majority of Cubans speak it. Spanish as spoken in Cuba is known as Cuban Spanish and is a form of Caribbean Spanish. Lucumi, a dialect of the West African language Yoruba, is also used as a liturgical language by practitioners of Santería,[154] and so only as a second language.[155] Haitian Creole is the second largest language in Cuba, and is spoken by Haitian immigrants and their descendants.[156] Other languages spoken by immigrants include Catalan and Corsican.[157]

Education[edit]

The University of Havana was founded in 1728 and there are a number of other well-established colleges and universities. In 1957, just before Castro came to power, the literacy rate was fourth in the region at almost 80% according to the United Nations, higher than in Spain.[58][158] Castro created an entirely state-operated system and banned private institutions. School attendance is compulsory from ages six to the end of basic secondary education (normally at age 15), and all students, regardless of age or gender, wear school uniforms with the color denoting grade level. Primary education lasts for six years, secondary education is divided into basic and pre-university education.[159]

Higher education is provided by universities, higher institutes, higher pedagogical institutes, and higher polytechnic institutes. The Cuban Ministry of Higher Education operates a scheme of distance education which provides regular afternoon and evening courses in rural areas for agricultural workers. Education has a strong political and ideological emphasis, and students progressing to higher education are expected to have a commitment to the goals of Cuba.[159] Cuba has provided state subsidized education to a limited number of foreign nationals at the Latin American School of Medicine.[160][161] Internet access is limited.[162] The sale of computer equipment is strictly regulated. Internet access is controlled, and e-mail is closely monitored.[97]

Health[edit]

Historically, Cuba has ranked high in numbers of medical personnel and has made significant contributions to world health since the 19th century.[58] Today, Cuba has universal health care and although shortages of medical supplies persist, there is no shortage of medical personnel.[163] Primary care is available throughout the island and infant and maternal mortality rates compare favorably with those in developed nations.[163]

Post-Revolution Cuba initially experienced an overall worsening in terms of disease and infant mortality rates in the 1960s when half its 6,000 doctors left the country.[164] Recovery occurred by the 1980s.[49] The Communist government asserted that universal health care was to become a priority of state planning and progress was made in rural areas.[165] Like the rest of the Cuban economy, Cuban medical care suffered from severe material shortages following the end of Soviet subsidies in 1991, followed by a tightening of the U.S. embargo in 1992.[166]

Challenges include low pay of doctors (only $15 a month[167]), poor facilities, poor provision of equipment, and frequent absence of essential drugs.[168] Cuba has the highest doctor-to-population ratio in the world and has sent thousands of doctors to more than 40 countries around the world.[169]

According to the UN, the life expectancy in Cuba is 78.3 years (76.2 for males and 80.4 for females). This ranks Cuba 37th in the world and 3rd in the Americas, behind only Canada and Chile, and just ahead of the United States. Infant mortality in Cuba declined from 32 infant deaths per 1,000 live births in 1957, to 10 in 1990–95.[170] Infant mortality in 2000–2005 was 6.1 per 1,000 live births (compared to 6.8 in the United States).

The quality of public healthcare offered to citizens is regarded as the "greatest triumph" of Cuba's socialist system.[171]

Culture[edit]

Cuban culture is influenced by its melting pot of cultures, primarily those of Spain and Africa. Sport is Cuba's national passion. Due to historical associations with the United States, many Cubans participate in sports which are popular in North America, rather than sports traditionally promoted in other Spanish-speaking nations. Baseball is by far the most popular; other sports and pastimes include basketball, volleyball, cricket, and athletics. Cuba is a dominant force in amateur boxing, consistently achieving high medal tallies in major international competitions.

Music[edit]

Cuban music is very rich and is the most commonly known expression of culture. The central form of this music is Son, which has been the basis of many other musical styles like salsa, rumba and mambo and an upbeat derivation of the rumba, the cha-cha-cha. Rumba music originated in early Afro-Cuban culture. The Tres was also invented in Cuba, but other traditional Cuban instruments are of African origin, Taíno origin, or both, such as the maracas, güiro, marimba and various wooden drums including the mayohuacan. Popular Cuban music of all styles has been enjoyed and praised widely across the world. Cuban classical music, which includes music with strong African and European influences, and features symphonic works as well as music for soloists, has received international acclaim thanks to composers like Ernesto Lecuona. Havana was the heart of the rap scene in Cuba when it began in the 1990s. During that time, reggaetón was growing in popularity. Dance in Cuba has taken a major boost over the 1990s.

Cuisine[edit]

Cuban cuisine is a fusion of Spanish and Caribbean cuisines. Cuban recipes share spices and techniques with Spanish cooking, with some Caribbean influence in spice and flavor. Food rationing, which has been the norm in Cuba for the last four decades, restricts the common availability of these dishes.[172] The traditional Cuban meal is not served in courses; all food items are served at the same time. The typical meal could consist of plantains, black beans and rice, ropa vieja (shredded beef), Cuban bread, pork with onions, and tropical fruits. Black beans and rice, referred to as Platillo Moros y Cristianos (or moros for short), and plantains are staples of the Cuban diet. Many of the meat dishes are cooked slowly with light sauces. Garlic, cumin, oregano, and bay leaves are the dominant spices.

Literature[edit]

Cuban literature began to find its voice in the early 19th century. Dominant themes of independence and freedom were exemplified by José Martí, who led the Modernist movement in Cuban literature. Writers such as Nicolás Guillén and Jose Z. Tallet focused on literature as social protest. The poetry and novels of Dulce María Loynaz and José Lezama Lima have been influential. Romanticist Miguel Barnet, who wrote Everyone Dreamed of Cuba, reflects a more melancholy Cuba.[173] Writers such as Reinaldo Arenas, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and more recently Daína Chaviano, Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, Zoé Valdés, Guillermo Rosales and Leonardo Padura have earned international recognition in the post-revolutionary era, though many of these writers have felt compelled to continue their work in exile due to ideological control of media by the Cuban authorities.

Havana[edit]

Havana | |

|---|---|

| La Habana | |

| Nickname: City of Columns | |

| Coordinates: 23°08′N 082°23′W / 23.133°N 82.383°W | |

| Country | Cuba |

| Province | La Habana |

| Founded | 1515(a) |

| City status | 1592 |

| Founded by | Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar |

| Municipalities | 15 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Marta Hernandez Romero (PCC) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 728.26 km2 (281.18 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 59 m (194 ft) |

| Population (2010)Official census[174] | |

| • Total | 2,135,498 |

| • Density | 2,932.3/km2 (7,595/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | habanero (m), habanera (f) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Postal code | 10xxx–19xxx |

| Area code | (+53) 7 |

| (a) Founded on the present site was founded in 1519. | |

Havana (Spanish: ⓘ, Spanish pronunciation: [la a'ßana]), is the capital city, major port, and leading commercial centre of Cuba. The city is one of the 15 Cuban provinces. The city/province has 2.1 million inhabitants,[174] the largest city in Cuba and (city proper population) in the Caribbean region.[175] The city extends mostly westward and southward from the bay, which is entered through a narrow inlet and which divides into three main harbours: Marimelena, Guanabacoa, and Atarés. The sluggish Almendares River traverses the city from south to north, entering the Straits of Florida a few miles west of the bay.

Havana was founded by the Spanish in the 16th century and due to its strategic location it served as a springboard for the Spanish conquest of the continent becoming a stopping point for the treasure laden Spanish Galleons on the crossing between the New World and the Old World. King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City in 1592.[176] The Spaniards began building fortifications, and in 1553 they transferred the governor's residence to Havana from Santiago de Cuba on the eastern end of the island, thus making Havana the de facto capital. The importance of harbour fortifications was early recognized as English, French, and Dutch sea marauders attacked the city in the 16th century.[177] The sinking of the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana's harbor in 1898 was the immediate cause of the Spanish-American War.[178]

Contemporary Havana can essentially be described as three cities in one: Old Havana, Vedado, and the newer suburban districts. Present day, the city is the center of the Cuban government, and various ministries and headquarters of businesses are based there.

History[edit]

Conquistador Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar founded Havana on August 25, 1515 or 1514, on the southern coast of the island, near the present town of Surgidero de Batabanó, or more likely on the banks of the Mayabeque River close to Playa Mayabeque. All attempts to found a city on Cuba's south coast failed, however an early map of Cuba drawn in 1514 places the town at the mouth of this river.[179][180](in Spanish). Between 1514 and 1519, the city had at least two different establishments on the north coast, one of them in La Chorrera, today in the neighborhood of Puentes Grandes, next to the Almendares River. The final city's location was adjacent to what was then called Puerto de Carenas (literally, "Careening Bay"), in 1519. The quality of this natural bay, which now hosts Havana's harbor, warranted this change of location.

Havana was the sixth town founded by the Spanish on the island, called San Cristóbal de la Habana by Pánfilo de Narváez: the name combines San Cristóbal, patron saint of Havana, and Habana, of obscure origin, possibly derived from Habaguanex, a native American chief who controlled that area, as mentioned by Diego Velasquez in his report to the king of Spain. Shortly after the founding of Cuba's first cities, the island served as little more than a base for the Conquista of other lands. Hernán Cortés organized his expedition to Mexico from the island.

Havana was originally a trading port, and suffered regular attacks by buccaneers, pirates, and French corsairs. The first attack and resultant burning of the city was by the French corsair Jacques de Sores in 1555. Such attacks convinced the Spanish Crown to fund the construction of the first fortresses in the main cities — not only to counteract the pirates and corsairs, but also to exert more control over commerce with the West Indies, and to limit the extensive contrabando (black market) that had arisen due to the trade restrictions imposed by the Casa de Contratación of Seville (the crown-controlled trading house that held a monopoly on New World trade).

Ships from all over the New World carried products first to Havana, in order to be taken by the fleet to Spain. The thousands of ships gathered in the city's bay also fueled Havana's agriculture and manufacture, since they had to be supplied with food, water, and other products needed to traverse the ocean.

On December 20, 1592, King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City. Later on, the city would be officially designated as "Key to the New World and Rampart of the West Indies" by the Spanish crown. In the meantime, efforts to build or improve the defensive infrastructures of the city continued.

Havana expanded greatly in the 17th century. New buildings were constructed from the most abundant materials of the island, mainly wood, combining various Iberian architectural styles, as well as borrowing profusely from Canarian characteristics.

In 1649 a fatal epidemic brought from Cartagena in Colombia, affected a third of the population of Havana. By the middle of the 18th century Havana had more than seventy thousand inhabitants, and was the third-largest city in the Americas, ranking behind Lima and Mexico City but ahead of Boston and New York.[181]

The city was captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. The episode began on June 6, 1762, when at dawn, a British fleet, comprising more than 50 ships and a combined force of over 11,000 men of the Royal Navy and Army, sailed into Cuban waters and made an amphibious landing east of Havana.[182] The British immediately opened up trade with their North American and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society. Less than a year after Havana was seized, the Peace of Paris was signed by the three warring powers thus ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain Florida in exchange for the city of Havana on the recommendation of the French, who advised that declining the offer could result in Spain losing Mexico and much of the South American mainland to the British.[183]

After regaining the city, the Spanish transformed Havana into the most heavily fortified city in the Americas. Construction began on what was to become the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña, the biggest Spanish fortification in the New World. On January 15, 1796, the remains of Christopher Columbus were transported to the island from Santo Domingo. They rested here until 1898, when they were transferred to Seville's Cathedral, after Spain's loss of Cuba.

As trade between Caribbean and North American states increased in the early 19th century, Havana became a flourishing and fashionable city. Havana's theaters featured the most distinguished actors of the age, and prosperity amongst the burgeoning middle-class led to expensive new classical mansions being erected. During this period Havana became known as the Paris of the Antilles.

In 1837, the first railroad was constructed, a 51 km stretch between Havana and Bejucal, which was used for transporting sugar from the valley of Guinness to the harbor. With this, Cuba became the fifth country in the world to have a railroad, and the first Spanish-speaking country. Throughout the century, Havana was enriched by the construction of additional cultural facilities, such as the Tacon Teatre, one of the most luxurious in the world. The fact that slavery was legal in Cuba until 1886 led to Southern American interest, including a plan by the Knights of the Golden Circle to create a 'Golden Circle' with a 1200 mile-radius centered on Havana. After the Confederate States of America were defeated in the American Civil War in 1865, many former slaveholders continued to run plantations by moving to Havana.

In 1863, the city walls were knocked down so that the metropolis could be enlarged. At the end of the 19th century, Havana witnessed the final moments of Spanish colonialism in the Americas.

Republican period and Post-revolution[edit]

The 20th century began with Havana, and therefore Cuba, under occupation by the United States.

During the Republican Period, from 1902 to 1959, the city saw a new era of development. Cuba recovered from the devastation of war to become a well-off country, with the third largest middle class in the hemisphere, and Havana, the Capital of the country, became known as the "Paris of the Caribbean". Apartment buildings to accommodate the new middle class, as well as mansions for the Cuban tycoons, were built at a fast pace. Numerous luxury hotels, casinos and nightclubs were constructed during the 1930s to serve Havana's burgeoning tourist industry. In the thirties, organized crime characters were not unaware of Havana's nightclub and casino life, and they made their inroads in the city. Santo Trafficante, Jr. took the roulette wheel at the Sans Souci Casino, Meyer Lansky directed the Hotel Habana Riviera, with Lucky Luciano at the Hotel Nacional Casino. At the time, Havana became an exotic capital of appeal and numerous activities ranging from marinas, grand prix car racing, musical shows and parks.

Havana achieved the title of being the Latin American city with the biggest middle class population per-capita, simultaneously accompanied by gambling and corruption where gangsters and stars were known to mix socially. During this era, Havana was generally producing more revenue than Las Vegas, Nevada. In 1958, about 300,000 American tourists visited the city.

After the revolution of 1959, the new regime promised to improve social services, public housing, and official buildings; nevertheless, shortages that affected Cuba after Castro's abrupt expropriation of all private property and industry under a strong communist model backed by the Soviet Union followed by the U.S. embargo, hit Havana especially hard. By 1966-68, the Cuban government had nationalized all privately owned business entities in Cuba, down to "certain kinds of small retail forms of commerce" (law No. 1076[184]).

There was a severe economic downturn after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. With it, subsidies ended, losing billions of dollars which the Soviet Union gave the Cuban government, with many believing Havana's soviet-backed regime would soon vanish, as happened to the Soviet satellite states of Eastern Europe. However, contrary to the soviet satellite states of Eastern Europe, Havana's communist regime prevailed during the 1990s.

After many years of prohibition, the communist government increasingly turned to tourism for new financial revenue, and has allowed foreign investors to build new hotels and develop hospitality industry. In Old Havana, effort has also gone into rebuilding for tourist purposes, and a number of streets and squares have been rehabilitated.[185] But Old Havana is a large city, and the restoration efforts concentrate in all but less than 10% of its area.

Geography[edit]

Havana lies on the northern coast of Cuba, south of the Florida Keys, where the Gulf of Mexico joins the Caribbean Sea (map at right). The city extends mostly westward and southward from the bay, which is entered through a narrow inlet and which divides into three main harbours: Marimelena, Guanabacoa, and Atarés. The sluggish Almendares River traverses the city from south to north, entering the Straits of Florida a few miles west of the bay.

The low hills on which the city lies rise gently from the deep blue waters of the straits. A noteworthy elevation is the 200-foot-high (60-metre) limestone ridge that slopes up from the east and culminates in the heights of La Cabaña and El Morro, the sites of colonial fortifications overlooking the eastern bay. Another notable rise is the hill to the west that is occupied by the University of Havana and the Prince's Castle. Outside the city, higher hills rise on the west and east.

Climate[edit]

Havana, like much of Cuba, enjoys a pleasant year-round tropical climate that is tempered by the island's position in the belt of the trade winds and by the warm offshore currents. Under the Köppen climate classification, Havana has a tropical savanna climate. Average temperatures range from 72 °F (22 °C) in January and February to 82 °F (28 °C) in August. The temperature seldom drops below 50 °F (10 °C). The lowest temperature was 33 °F (1 °C) in Santiago de Las Vegas, Boyeros. The lowest recorded temperature in Cuba was 32 °F (0 °C) in Bainoa, Havana province. Rainfall is heaviest in June and October and lightest from December through April, averaging 46 inches (1,200 mm) annually. Hurricanes occasionally strike the island, but they ordinarily hit the south coast, and damage in Havana has been less than elsewhere in the country.

The table below lists temperature averages throughout the year:

| Climate data for Havana | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.8 (78.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

29.2 (84.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 64.4 (2.54) |

68.6 (2.70) |

46.2 (1.82) |

53.7 (2.11) |

98.0 (3.86) |

182.3 (7.18) |

105.6 (4.16) |

99.6 (3.92) |

144.4 (5.69) |

180.5 (7.11) |

88.3 (3.48) |

57.6 (2.27) |

1,189.2 (46.84) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 80 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 74 | 73 | 72 | 75 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 77 | 75 | 76 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organisation (UN),[186] Climate-Charts.com[187] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape[edit]

Contemporary Havana can essentially be described as three cities in one: Old Havana, Vedado, and the newer suburban districts. Old Havana, with its narrow streets and overhanging balconies, is the traditional centre of part of Havana's commerce, industry, and entertainment, as well as being a residential area.

To the north and west a newer section, centred on the uptown area known as Vedado, has become the rival of Old Havana for commercial activity and nightlife. Centro Habana, sometimes described as part of Vedado, is mainly a shopping district that lies between Vedado and Old Havana. The Capitolio Nacional building marks the beginning of Centro Habana, a working class neighborhood.[188] Chinatown and the Real Fabrica de Tabacos Partagás, one of Cuba's oldest cigar factories is located in the area.[189]

A third Havana is that of the more affluent residential and industrial districts that spread out mostly to the west. Among these is Marianao, one of the newer parts of the city, dating mainly from the 1920s. Some of the suburban exclusivity was lost after the revolution, many of the suburban homes having been nationalized by the Cuban government to serve as schools, hospitals, and government offices. Several private country clubs were converted to public recreational centres. Miramar, located west of Vedado along the coast, remains Havana's exclusive area; mansions, foreign embassies, diplomatic residences, upscale shops, and facilities for wealthy foreigners are common in the area.[190] The International School of Havana is located in the Miramar neighborhood.

In the 1980s many parts of Old Havana, including the Plaza de Armas, became part of a projected 35-year multimillion-dollar restoration project, for Cubans to appreciate their past and boost tourism. In the past ten years, with the assistance of foreign aid and under the support of local city historian Eusebio Leal Spengler, large parts of Habana Vieja have been renovated. The city is moving forward with their renovations, with most of the major plazas (Plaza Vieja, Plaza de la Catedral, Plaza de San Francisco and Plaza de Armas) and major tourist streets (Obispo and Mercaderes) near completion.

Architecture[edit]

Due to Havana's more than five hundred year existence, the city boasts some of the most diverse styles of architecture in the world. From castles built in the late 16th century to modernist present-day high-rises.

- Neoclassical

Neoclassism was introduced into the city in the 1840s, at the time including Gas public lighting in 1848 and the railroad in 1837. In the second half of the 18th century, sugar and coffee production increased rapidly, which became essential in the development of Havana's most prominent architectural style. Many wealthy Habaneros took their inspiration from the French; this can be seen within the interiors of upper class houses such as the Aldama Palace built in 1844. This is considered the most important neoclassical residential building in Cuba and typifies the design of many houses of this period with portales of neoclassical columns facing open spaces or courtyards.

In 1925 Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier, the head of urban planning in Paris moved to Havana for five years to collaborate with architects and landscape designers. In the master planning of the city his aim was to create a harmonic balance between the classical built form and the tropical landscape. He embraced and connected the city's road networks while accentuating prominent landmarks. His influence has left a huge mark on Havana although many of his ideas were cut short by the great depression in 1929. During the first decades of the 20th century Havana expanded more rapidly than at any time during its history. Great wealth prompted architectural styles to be influenced from abroad. The peak of Neoclassicism came with the construction of the Vedado district (begun in 1859). This whole neighbourhood is littered with set back well-proportioned buildings.

- Colonial and Baroque

Riches were brought from the colonialists into and through Havana as it was a key transshipment point between the new world and old world. As a result Havana was the most heavily fortified city in the Americas. Most examples of early architecture can be seen in military fortifications such as La Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabana (1558–1577) designed by Battista Antonelli and the Castillo del Morro (1589–1630). This sits at the entrance of Havana Bay and provides an insight into the supremacy and wealth at that time.

Old Havana was also protected by a defensive wall begun in 1674 but had already overgrown its boundaries when it was completed in 1767, becoming the new neighbourhood of Centro Habana. The influence from different styles and cultures can be seen in Havana's colonial architecture, with a diverse range of Moorish architecture, Spanish, Italian, Greek and Roman. The San Carlos and San Ambrosio Seminary (18th century) is a good example of early Spanish influenced architecture. The Havana cathedral (1748–1777) dominating the Plaza de la Catedral (1749) is the best example of Cuban Baroque. Surrounding it are the former palaces of the Count de Casa-Bayona (1720–1746) Marquis de Arcos (1746) and the Marquis de Aguas Claras (1751–1775).

- Art Deco and Eclectic

The first echoes of the Art Deco movement in Havana started in 1927, in the residential area of Miramar.[191] The Edificio Bacardi (1930) is thought to be the best example of Art-deco architecture in the city and first tall Art Deco building as well,[191] followed by the Hotel Nacional de Cuba (1930) and The Lopez Serrano building built in 1932 by Ricardo Mira inspired by the Rockefeller Center in New York. The year 1928 marked the beginning of the reaction against the Spanish Renaissance style architecture, Art Deco started in the lush and wealthy suburbs of Miramar, Marianao, and Vedado.[191]

The city's eclectic architectural sights begins in Centro Habana.[192] The Central Railway Terminal (1912), and the Museum of the Revolution (1920) are example of Eclectic architecture.

|

- Modernism

Many high-rise office buildings, and apartment complexes, along with some hotels built in the 1950s dramatically altered the skyline. Modernism, therefore, transformed much of the city and should be noted for its individual buildings of high quality rather than its larger key buildings. Examples of the latter are Habana Libre (1958), which before the revolution was the Havana Hilton Hotel and La Rampa movie theater (1955).