User:Noorullah21/sandbox

| Humayun Sadozai | |

|---|---|

| Governor | |

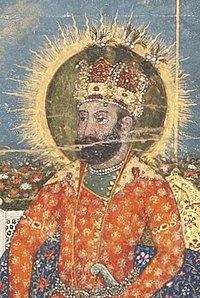

Portrait of Prince Humayun | |

| Governor of Kandahar | |

| Reign | 1793 |

| Predecessor | Timur Shah Durrani |

| Successor | Zaman Shah Durrani |

| Born | 1764 Herat, Durrani Empire (present day Afghanistan) |

| Dynasty | Durrani |

| Father | Timur Shah Durrani |

FOR HUMAYUN PAGE IN THE FUTURE (PORTRAIT)

| Zaman Shah Durrani زمان شاہ درانی | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah of the Durrani Empire | |||||

| |||||

| Emir of the Durrani Empire | |||||

| Reign | 20 May 1793 – 25 July 1801 | ||||

| Coronation | 1793 | ||||

| Predecessor | Timur Shah Durrani | ||||

| Successor | Mahmud Shah Durrani | ||||

| Born | 1767 | ||||

| Died | 1844 (aged 77) Ludhiana, Sikh Empire (Present day India) | ||||

| Burial | 1844 | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Durrani | ||||

| Father | Timur Shah Durrani | ||||

| Mother | Maryam Begum[1] | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Zaman Shah Durrani, or Zaman Shah Abdali, (Pashto/Dari: زمان شاہ درانی), (1767 – 1844) was ruler of the Durrani Empire from 1793 until 1801. He was the grandson of Ahmad Shah Durrani and the fifth son of Timur Shah Durrani. An ethnic Pashtun, Zaman Shah became the third King of the Durrani Empire.

Early Years[edit]

Zaman Shah Durrani was born as the son of Timur Shah Durrani. The date of his birth is disputed however. Fayz Muhammad gives 1767 as his birth date,[2] while Noelle-Karimi gives 1770 as his birth date.[3] Zaman Shah had always wanted to follow his father, Timur Shah Durrani with his conquests in Punjab, however Timur Shah Durrani did not allow it, and Zaman Shah very early grew interests of being like his grandfather, Ahmad Shah Durrani, as a child he had dreamt of conquering Hindustan, but to no avail in aid as his father did not allow him to come on his campaigns.

Death of Timur Shah Durrani[edit]

In May 1793, Zaman Shah's father, Timur Shah Durrani died, Timur Shah spent his winters at his winter capital of Peshawar, in the Bala Hissar. During this period of time, Timur Shah developed Hypochondriasis, falsely believing that he could be terminally ill.[4] His doctors could not find a cure for this, and blamed it on the climate of Peshawar as a whole.[4] Showing symptoms of Fever, Timur Shah set out to Kabul with winter coming to a close, as he usually in routine lived in Kabul during the summer, and Peshawar during the winter. Prince Zaman, hearing of the Shah's illness set out to meet him at Char Bagh.[4] The Shah, happy kissed Zaman's forehead and attempted to continue his journey to Kabul, leaving Jalalabad. One night, while stopping, he described in a dream he saw to Zaman and Qazi Fayzullah that he saw his crown being lifted to his son, Zaman Shah Durrani.[4] On 18 or 20 May, 1793, Timur Shah passed away from his illness.[5]

- "Two images have come to rest, the one yearned.

- For the other, inspiring dread.

- The sun has risen from the horizon, the moon has sunk to rest.

- Like the cycle of sun and moon, Timur the throne descends,

- And now the regent Zaman Shah ascends."

Reign[edit]

(FOR ZAMAN SHAH DURRANI) -------------------

Medieval history[edit]

Islamic conquest[edit]

Arab Muslims brought Islam to Herat and Zaranj in 642 CE and began spreading eastward; some of the native inhabitants they encountered accepted it while others revolted. Before the arrival of Islam, the region used to be home to various beliefs and cults, often resulting in Syncretism between the dominant religions[6][7] such as Zoroastrianism,[8][9][10] Buddhism or Greco-Buddhism, Ancient Iranian religions,[11] Hinduism, Christianity[12] [13] and Judaism.[14][15] An exemplification of the syncretism in the region would be that people were patrons of Buddhism but still worshipped local Iranian gods such as Ahura Mazda, Lady Nana, Anahita or Mihr(Mithra) and portrayed Greek Gods like Heracles or Tyche as protectors of Buddha.[16][17][18] The Zunbils and Kabul Shahi were first conquered in 870 CE by the Saffarid Muslims of Zaranj. Later, the Samanids extended their Islamic influence south of the Hindu Kush. It is reported that Muslims and non-Muslims still lived side by side in Kabul before the Ghaznavids rose to power in the 10th century.[19][20][21]

By the 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni defeated the remaining Hindu rulers and effectively Islamized the wider region,[22] with the exception of Kafiristan.[23] Mahmud made Ghazni into an important city and patronized intellectuals such as the historian Al-Biruni and the poet Ferdowsi.[24] The Ghaznavid dynasty was overthrown by the Ghurids, whose architectural achievements included the remote Minaret of Jam. The Ghurids controlled Afghanistan for less than a century before being conquered by the Khwarazmian dynasty in 1215.[25]

Mongols and Babur with the Lodi Dynasty[edit]

In 1219 CE, Genghis Khan and his Mongol army overran the region. His troops are said to have annihilated the Khwarazmian cities of Herat and Balkh as well as Bamyan.[26] The destruction caused by the Mongols forced many locals to return to an agrarian rural society.[27] Mongol rule continued with the Ilkhanate in the northwest while the Khalji dynasty, a Turko-Afghan dynasty ruling in India at the time administered the Afghan tribal areas south of the Hindu Kush. Timur aka (Tamerlane) invaded the region in 1370 and established the Timurid Empire. Under the rule of Shah Rukh the city[which?] served as the focal point of the Timurid Renaissance, whose glory matched Florence of the Italian Renaissance as the center of a cultural rebirth.[28][29]

Afghan Diaspora and their Empires (1290-1761)[edit]

Khalji Dynasty and their origins[edit]

The Khaljis of the Khalji Dynasty were of Turko-Afghan[30][31][32][33] origin whose ancestors, the Khalaj, are said to have been initially a Turkic people who migrated together with the Iranian Huns and Hephthalites[34] from Central Asia, into the southern and eastern regions of modern-day Afghanistan as early as 660CE, where they ruled the region of Kabul as the Buddhist Kabul Shahis.[35] From the very beginning, the Khalaj were going through a process of assimilation into the Pashtun tribal system. During their reign in India, they were already treated entirely as Afghans by the Turkic nobles of the Delhi Sultanate.[36][37][38]

The modern Pashto-speaking Ghilji Pashtuns, who make up the majority of the Pashtuns in Afghanistan, are the modern result of the Khalaj assimilation into the Pashtuns. Between the 10th and 13th centuries, some sources refer to the Khalaj people as of Turkic, but some others do not.[39] Minorsky argues that the early history of the Khalaj tribe is obscure and adds that the identity of the name Khalaj is still to be proved.[40] Mahmud al-Kashgari (11th century) does not include the Khalaj among the Oghuz Turkic tribes, but includes them among the Oghuz-Turkman (where Turkman meant "Like the Turks") tribes. Kashgari felt the Khalaj did not belong to the original stock of Turkish tribes but had associated with them and therefore, in language and dress, often appeared "like Turks".[39] The 11th century Tarikh-i Sistan and the Firdausi's Shahnameh also distinguish and differentiate the Khalaj from the Turks.[41] Minhaj-i-Siraj Juzjani (13th century) never identified Khalaj as Turks, but was careful not to refer to them as Pashtuns. They were always a category apart from Turks, Tajiks and Pashtuns.[42] Muhammad ibn Najib Bakran's Jahan-nama explicitly describes them as Turkic,[43] although he notes that their complexion had become darker (compared to the Turks) and their language had undergone enough alterations to become a distinct dialect. The modern historian Irfan Habib has argued that the Khaljis were not related to the Turkic people and were instead ethnic Pashtuns. Habib pointed out that, in some 15th-century Devanagari Sati inscriptions, the later Khaljis of Malwa have been referred to as "Khalchi" and "Khilchi", and that the 17th century chronicle Padshahnama, an area near Boost in Afghanistan (where the Khalaj once resided) as "Khalich". Habib theorizes that the earlier Persian chroniclers misread the name "Khalchi" as "Khalji" . He also argues that no 13th century source refers to the Turkish background of the Khalji. However, Muhammad ibn Najib Bakran's Jahan-nama (c. 1200-1220) described the Khalaj people as a "tribe of Turks" that had been going through a language shift.[43]

Khalji Revolution of Delhi[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Consolidation of power under Jalalauddin Khalji[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Assassination of Jalalauddin Khalji[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Reign of Alauddin Khalji[edit]

Death of Alauddin Khalji and fall of the Khaljis[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Afghan Diaspora and influence in the Delhi Sultanates[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Rise of the Lodis[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Babur and Fall of the Lodis[edit]

In the early 16th century, Babur arrived from Ferghana and captured Kabul from the Arghun dynasty.[44] After failing in his attempts at campaigning in Samarkand, Babur saw elsewhere to expand into, setting his eyes into Punjab to fulfill his ancestor, Timur's legacy. in 1524, he recieved invitations from Daulat Khan Lodi the governor of Punjab, and Ala-ud-din, Uncle to Ibrahim Lodi[45] Following this, Babur sent an ambassador to Ibrahim Lodi, claiming himself as the rightful ruler to the Delhi Sultanate and Lodi dynasty. This ambassador was detained at Lahore, but released later.[46] Babur set out for Lahore in 1524, and heard news that Daulat Khan Lodi was stripped of his position and forced to flee after Ibrahim Lodi sent forces.[47] Babur arrived at Lahore, and the Lodi army marched out, only to be routed. Babur then marched to Dibalpur, placing Alam Khan, another rebel uncle of Ibrahim Lodi as governor.[48] Alam Khan was quickly overthrown however, and fled to Kabul. Babur then supplied Alam Khan with troops who later joined up with Daulat Khan Lodi, and together united to around 30,000 men. They then marched to Delhi and besieged the city against Ibrahim Lodi.[49] However, despite odds against him, Ibrahim Lodi drove off and routed the army of Alam Khan.[49] In November 1525 Babur got news at Peshawar that Daulat Khan Lodi had switched sides, and Babur drove out Ala-ud-Din. Babur then marched onto Lahore to confront Daulat Khan Lodi, only to see Daulat's army melt away at their approach. Daulat surrendered and was pardoned. Thus within three weeks of crossing the Indus River Babur had become the Ruler of Punjab.[citation needed]

Babur marched on to Delhi via Sirhind. He reached Panipat on 20 April 1526 and there met Ibrahim Lodi's numerically superior army of about 100,000 soldiers and 100 elephants.[50][45] In the battle that began on the following day, Babur used the tactic of Tulugma, encircling Ibrahim Lodi's army and forcing it to face artillery fire directly, as well as frightening its war elephants.[45] Ibrahim Lodi died during the battle, thus ending the Lodi dynasty.[50]

Reign of the Mughals and the Afghan Influence[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Uprising of Sher Shah Suri[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Toppling of the Mughals[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Death of Sher Shah and his Successors[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Return of the Mughals and Second Battle of Panipat[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

- ^ The History of Afghanistan (6 vol. set) Fayż Muḥammad Kātib Hazārah’s Sirāj al-tawārīkh. Editors: Robert McChesney and Moh

- ^ Hazārah, Fayz̤ Muḥammad Kātib (2013). The History of Afghanistan: Fayz Muhammad Katib Hazarah's Siraj Al-tawarikh. Brill.

- ^ Christine Noelle-Karimi (2014). The Pearl In Its Midst By Christine Noelle Karimi.

- ^ a b c d Muhammad Katib Hazarah 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Muhammad Katib Hazarah 2012, p. 71.

- ^ Weber, Olivier; Unesco (2002). Eternal Afghanistan. Chêne. ISBN 978-92-3-103850-1.

Gradually there emerged a fabulous syncretism between the Hellenistic world and the Buddhist universe

- ^ Grenet, Grenet (2016). Zoroastriansm among the Kushans.

- ^ Gnoli, Gherado (1989). The Idea of Iran, an Essay on its Origin. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. p. 133.

... he would have drawn inspiration from a ireligious policy which intended to counteract the Median Magi's influence and transfer the 'Avesta-Schule' from Arachosia to Persia: thus the Avesta would have arrived in Persia through Arachosia in the 6th century B.C. [...] Alltough [...] Arachosia would have been only a second fatherland for Zoroastrianism, a significant role should still be attributed to this south-eastern region in the history of the Zoroastrian tradition.

- ^ Gnoli, Gherado (1989). The Idea of Iran, an essay on its Origin. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. p. 133.

linguistic data [...] prove the presence of the Zoroastrian tradition in Arachosia both in the Achaemenian age, in the last quarter of the 6th century, and in the Seleucid age.

- ^ "ARACHOSIA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Allen, Charles (5 November 2015). The Search For Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-349-14218-0.

With Aurmuzd, Sroshard, Narasa and Mihr, we are on safer ground because all are Zoroastrian deities: Aurmuzd is the supreme god of light, Ahura Mazda; and Mihr, the sun god, is linked with the Iranian Mithra. Exactly the same non-Buddhist[...]

- ^ Gorder, A. Christian Van (2010). Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-muslims in Iran. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-3609-6.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (9 December 2010). The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-86559-9.

.. when the patriarch at Ctesiphon had to broker a compromise that left one bishop at the capital Zaranj and another further east at Bust, now in southern Afghanistan. A Christian text composed in about 850 also records a monastery of ...

- ^ Yossef, Noam Bar'am-Ben (1998). Brides and Betrothals: Jewish Wedding Rituals in Afghanistan. Israel Museum. ISBN 978-965-278-223-6.

The Jews of Afghanistan According to tradition , the first Jews reached ... in Hebrew script found in the Tang - e Azao Valley in the Ghor region ...

- ^ Ende, Werner; Steinbach, Udo (15 April 2010). Islam in the World Today: A Handbook of Politics, Religion, Culture, and Society. Cornell University Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780801464898.

At the time of the first Muslim advances, numerous local natural religions were competing with Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Hinduism in the territory of modern Afghanistan.

- ^ Adrych, Philippa; coins), Robert Bracey (Writer on; Dalglish, Dominic; Lenk, Stefanie; Wood, Rachel (2017). Images of Mithra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879253-6.

The Rabatak inscription includes Miiro amongst a list of gods: Nana, Ahura Mazda, and Narasa. All of these gods likely had images dedicated at the Bagolaggo, presumably alongside statues of Kanishka

- ^ Allen, Charles (5 November 2015). The Search For Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-349-14218-0.

With Aurmuzd, Sroshard, Narasa and Mihr, we are on safer ground because all are Zoroastrian deities: Aurmuzd is the supreme god of light, Ahura Mazda; and Mihr, the sun god, is linked with the Iranian Mithra. Exactly the same non-Buddhist[...]

- ^ Allen, Charles (5 November 2015). The Search For Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-349-14218-0.

The two most important deities are goddesses: one is the lady Nana', daughter of the moon god and sister of the sun god, the Kushan form of Anahita, Zoroastrian goddess of fertility

- ^ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Hamd-Allah Mustawfi of Qazwin (1340). "The Geographical Part of the NUZHAT-AL-QULUB". Translated by Guy Le Strange. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.3)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Ewans 2002, p. 22-23.

- ^ Richard F. Strand (31 December 2005). "Richard Strand's Nuristân Site: Peoples and Languages of Nuristan". nuristan.info. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Richard Nyrop; Donald Seekins, eds. (1986). Afghanistan: A Country Study. Foreign Area Studies, The American University. p. 10.

- ^ Ewans 2002, p. 23.

- ^ "Central Asian world cities". Faculty.washington.edu. 29 September 2007. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Page, Susan (18 February 2009). "Obama's war: Deploying 17,000 raises stakes in Afghanistan". USA Today. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ Periods of World History: A Latin American Perspective – Page 129

- ^ The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia – Page 465

- ^ Khan, Yusuf Husain (1971). Indo-Muslim Polity (Turko-Afghan Period). Indian Institute of Advanced Study.

- ^ Society, Pakistan Historical (1995). Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. Pakistan Historical Society.

Bengal long before the formal Turco - Afghan conquest conducted by Bakhtiyar Khalji * at the end of the twelfth century . Although Islamic state power came to Bengal by ...

- ^ Fisher, Michael H. (18 October 2018). An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-11162-2.

In 1290, the Turk-Afghan Khalji clan ended the first mamluk dynasty and then ruled in Delhi until one of their own Turkish mamluk commanders rebelled and established his own Tugluq dynasty

- ^ Bose, Saikat K. (20 June 2015). Boot, Hooves and Wheels: And the Social Dynamics behind South Asian Warfare. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-84464-54-7.

... by the Turco–Afghan dynasty of the Khiljis.5 Aybak and Iltutmish, who campaigned with ambivalent success in Rajputana, had encouraged an independent adventurer called Muhammad b. Bakhtyar Khilji (different from the Khilji sultans and ..

- ^ "ḴALAJ i. TRIBE – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ^ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017-03-15). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4744-0030-5.

A Bactrian Document (BD T) from this period brings interesting information about the area to our attention. In it, dated to BE 476 (701 AD), a princess identified as `Bag-aziyas, the Great Turkish Princess, the Queen of Qutlugh Tapaghligh Bilga Sävüg, the Princess of the Khalach, the Lady of Kadagestan offers alms to the local god of the region of Rob, known as Kamird, for the health of (her) child. Inaba, arguing for the Khalaj identity of the kings of Kabul, takes this document as a proof that the Khalaj princess is from Kabul and has been offered to the (Hephthalite) king of Kadagestan, thus becoming the lady of that region. The identification of Kadagestan as a Hephthalite stronghold is based on Grenet's suggestion of the survival of Hephthalite minor stares in this region,' and is in con-

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ashirbadi2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Abraham Eraly (2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin Books. p. 126. ISBN 978-93-5118-658-8:"The prejudice of Turks was however misplaced in this case, for Khaljis were actually ethnic Turks. But they had settled in Afghanistan long before the Turkish rule was established there, and had over the centuries adopted Afghan customs and practices, intermarried with the local people, and were therefore looked down on as non-Turks by pure-bred Turks."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic. p. 28. ISBN 81-269-0123-3:"The Khaljis were a Turkish tribe but having been long domiciled in Afghanistan, had adopted some Afghan habits and customs. They were treated as Afghans in Delhi Court. They were regarded as barbarians. The Turkish nobles had opposed the ascent of Jalal-ud-din to the throne of Delhi."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Sunil Kumar 1994, p. 36.

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani 1999, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1540-7.

- ^ Sunil Kumar (1994). "When Slaves were Nobles: The Shamsi Bandagan in the Early Delhi Sultanate". Studies in History. 10 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1177/025764309401000102. S2CID 162388463.

- ^ a b Sunil Kumar 1994, p. 31.

- ^ Barfield 2012, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of medieval India : from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. New Delhi: Atlantic Publ. pp. 89–90. ISBN 81-269-0123-3.

- ^ Mahajan 1980, p. 429.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2009). Medieval India:From Sultanat to the Mughals. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Har-Anand. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-241-1268-7.

- ^ Chandra (2009, pp. 27–28)

- ^ a b Chandra (2009, p. 28)

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

VDM0was invoked but never defined (see the help page).