Suzanne Ferrière: Difference between revisions

RomanDeckert (talk | contribs) I created this article on the occasion of the "Schreibabend" by Wikimedia CH and as a contribution to the "Women in Europe contest 2021" of the WikiProject Women in Red, partly copied from Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Lucie Odier and Marguerite Gautier-van Berchem which I all wrote myself. Conflict of interest disclosure: my beloved wife is an ICRC delegate which gives me a romantic affiliation with the subject, but does not necessarliy mean that my edits are romanticising it! |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 00:58, 30 June 2021

Suzanne Ferrière | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signature | |

|

Anne Suzanne "Lili" Ferrière (22 March 1886, Geneva – 13 March 1970, Geneva) was a Swiss dance teacher of Dalcroze eurhythmics and a humanitarian activist. As only the second female member of the governing body of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) she helped to pave the way towards gender equality in the organisation which itself has historically been a pioneer of international humanitarian law.[1]

Life

Family background and early years

The Ferrière-family reportedly originated from the Normandy and moved to Besançon in Eastern France, close to the Jura Mountains and the border with Switzerland, around 1700.[2] From there they arrived in the republic of Geneva some forty years later. Since they were a family of protestant pastors, it seems plausbile that they escaped repressions which arose after Louis XIV in 1685 revoked the 1598 Edict of Nantes, which had restored some civil rights to the Huguenots. In 1781, the family obtained Genevan citizenship.[1]

Suzanne Ferrière's father Louis (1842-1928) was a pastor as well, who supported the philantropic Union nationale évangélique and the social Christianity movement.[1] His wife Hedwig Marie Therese, née Faber (1859-1928), hailed from Vienna,[3] and her older sister Adolphine was married to his younger brother Frederic.[4] Suzanne was the second-oldest child of five. She had two brothers and two sisters: Jean Auguste (1884-1968), Louis Emmanuel (1887-1963), Marguerite Louise Hedwige (1890-1984), and Juliette Jeanne Adolphine (1895-1970).[5]

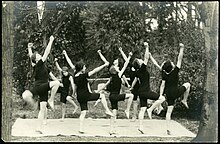

In the 1900s, Suzanne Ferrière became a student of the Swiss composer Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, who was Professor of Harmony at the Conservatoire de Musique de Genève since 1892. In his solfège courses he stested many of his influential and revolutionary pedagogical ideas. In 1910, he left and established his own academy in Hellerau, near Dresden, where many great exponents of modern dance in the twentieth century spent time at the school. Suzanne Ferrière was one of the 46 students from Geneva who joined Jaques-Dalcroze.[6] In 1911 she obtained her diploma and immediately started teaching.[7] In her class she developed her own variant of the eurhythmics, which was inspired by dancing elements and became known as exercices de plastique animée.[8]

Around 1914, Jaques-Dalcroze sent Ferriere to the USA.[9] There she worked to establish the New York Dalcroze School of Music, which started its activities in 1915. Ferrière was supposed to be its first directress,[10] but had to return to Geneva:

First World War

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the ICRC under its president Gustave Ador established the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA) to trace POWs and to re-establish communications with their respective families. The Austrian writer and pacifist Stefan Zweig described the situation at the Geneva headquarters of the ICRC as follows:

«Hardly had the first blows been struck when cries of anguish from all lands began to be heard in Switzerland. Thousands who were without news of fathers, husbands, and sons in the battlefields, stretched despairing arms into the void. By hundreds, by thousands, by tens of thousands, letters and telegrams poured into the little House of the Red Cross in Geneva, the only international rallying point that still remained. Isolated, like stormy petrels, came the first inquiries for missing relatives; then these inquiries themselves became a storm. The letters arrived in sackfuls. Nothing had been prepared for dealing with such an inundation of misery. The Red Cross had no space, no organization, no system, and above all no helpers.»[11]

Already at the end of the same year though, the Agency had some 1,200 volunteers who worked in the Musée Rath of Geneva, amongst them the French writer and pacifist Romain Rolland. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for 1915, he donated half of the prize money to the Agency.[12] Most of the staff were women though, including Suzanne Ferrière.

Their mandate was based on resolution VI of the 9th Red Cross movement conference of Washington in 1912 and hence limited to military personnel. However, Suzanne's uncle, the committee member and medical doctor Frédéric Ferrière, founded a civilian section against the advice of other committee members. It soon became commonly associated with the ICRC and significantly contributed to its positive image, thus also to its first Nobel Peace Prize in 1917 (The ousted Dunant had received the first one in 1901 as an individual).[13]

Between the World Wars

Starting from December 1923, Ferrière toured Latin America for ten months as a delegate of the ICRC to visit the newly founded national red ross societies, crossing over the Andes on donkey-back. The trip led her from Brazil to Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela. As the main overall result she stressed the social role that women played in those countries.[14]

In August 1925, Ferrière was elected a member of the ICRC as only the second woman ever to join the governing body of the organisation after Marguerite (Frick-)Cramer in 1919.[1]

In May 1929, Ferrière visited the French colonies of Lebanon and Syria to evaluate the situation with regard to the many Armenian genocide survivors who newly arrived from Turkey.[15]

Second World War

In early 1943, Ferrière and her fellow female ICRC pioneer Lucie Odier conducted a joint mission to the Middle East and Africa to assess the situation of civilian detainees. Their tour of three months duration included stops in Istanbul, Ankara, Cairo, Jerusalem, Beirut, Johannesburg, Salisbury, and Nairobi.[16]

Post-WWII

The obituary in the International Review of the Red Cross honoured her as a

«a warmhearted woman who had devoted her life to her fellow men with calm courage and exemplary modesty.»[17]

References

- ^ a b c d Fiscalini, Diego (1985). Des élites au service d'une cause humanitaire : le Comité International de la Croix-Rouge (in French). Geneva: Université de Genève, faculté des lettres, département d'histoire. pp. 24, 160–162.

- ^ "Généalogie de la famille Ferrière (de Genève)". archives-ferriere.nexgate.ch. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Hedwige _ , Marie, Thérese, C." Geneanet. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Adolphine _ , Thérèse, Caroline, Katharine Faber". Geneanet. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Anne Suzanne (Lili) Ferriere". Geneanet. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Kamp, Johannes-Martin (1995). Kinderrepubliken (in Deutsch). Opladen: Leske + Budrich. p. 332. ISBN 3-8100-1357-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Berchtold, Alfred (2000). Emile Jaques-Dalcroze et son temps. Lausanne: L'AGE D'HOMME. pp. 118, 185. ISBN 978-2825113547.

- ^ "Methode Jaques-Dalcroze (MJD) – Orff-Schulwerk" (in German). Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Nathan (1995). Dalcroze Eurhythmics and Rhythm Training for Actors in American Universities. East Lansing: Michigan State University. Department of Theatre. p. 48.

- ^ Wieland Howe, Sondra (2014). Women Music Educators in the United States: A History. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press. p. 246. ISBN 9780810888470.

- ^ Zweig, Stefan (1921). Romain Rolland; the man and his work. Translated by Eden, Paul; Cedar, Paul. Translated by Eden, Paul; Cedar, Paul. New York: T. Seltzer. p. 268.

- ^ Schazmann, Paul-Emile (February 1955). "Romain Rolland et la Croix-Rouge: Romain Rolland, Collaborateur de l'Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross (in French). 37 (434): 140–143. doi:10.1017/S1026881200125735.

- ^ Ferrière, Adolphe (1948). Le Dr Frédéric Ferrière. Son action à la Croix-Rouge internationale en faveur des civils victimes de la guerre (in French). Geneva: Editions Suzerenne, Sarl. pp. 27–41.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Ferrière, Suzanne (September 1924). "Les Croix-Rouges de l'Amérique du Sud" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 71: 853–870.

- ^ Ferrière, Suzanne (January 1930). "Voyage en Syrie" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 133: 7–14.

- ^ Odier, Lucie (September 1943). "Mission en Afrique" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 25 (297): 730–743.

- ^ "Death of Miss S. Ferriere, Honorary Member of the ICRC" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 109: 210–211. April 1970.