Joseph Vallot: Difference between revisions

Nick Moyes (talk | contribs) →Mont Blanc Observatories: merge 2 para sharing the same refs. |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Alter: journal, pages, url, issue. URLs might have been anonymized. Add: s2cid, doi, issue, pmid, authors 1-1. Removed parameters. Formatted dashes. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by AManWithNoPlan | #UCB_webform 625/1354 |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

== Life == |

== Life == |

||

[[File:Joseph Vallot at 12 years.jpg|left|thumb|Joseph Vallot at 12 years of age.]] |

[[File:Joseph Vallot at 12 years.jpg|left|thumb|Joseph Vallot at 12 years of age.]] |

||

Joseph Vallot was born on 16 February 1854 at [[Lodève]] in southern [[France]]. His father was Émile Vallot and he had a cousin, Henri - both of whom Joseph collaborated professionally with in later life.<ref name="MerdeGlace">{{cite book|url=http://www.persee.fr/doc/aommb_2015-7509_1898_num_3_1_967|title=Annales de l'Observatoire météorologique physique et glaciaire du Mont-Blanc|last1=Vallot|first1=J.|year=1898|editor-last=Steinheil|editor-first=G.|location=Paris|pages=190–193|language=fr|chapter=Exploration des moulins de la mer de glace: Forage de M. Émile Vallot|volume=3}}</ref>. Vallot's family were wealthy, having made their fortunes in the dye and textile business, and this allowed him to pursue and fund his many grand scientific undertakings throughout his life. Joseph Vallot received a classical education in Paris, first at the [[Lycée Charlemagne]] and then the [[Sorbonne]].<ref name="Qui">{{Cite book|url=http://archive.org/details/quitesvousannua00unkngoog|title=Qui êtes-vous? Annuaire des contemporains: notices biographiques|date=1924|publisher=La Librairie Delagrave |

Joseph Vallot was born on 16 February 1854 at [[Lodève]] in southern [[France]]. His father was Émile Vallot and he had a cousin, Henri - both of whom Joseph collaborated professionally with in later life.<ref name="MerdeGlace">{{cite book|url=http://www.persee.fr/doc/aommb_2015-7509_1898_num_3_1_967|title=Annales de l'Observatoire météorologique physique et glaciaire du Mont-Blanc|last1=Vallot|first1=J.|year=1898|editor-last=Steinheil|editor-first=G.|location=Paris|pages=190–193|language=fr|chapter=Exploration des moulins de la mer de glace: Forage de M. Émile Vallot|volume=3}}</ref>. Vallot's family were wealthy, having made their fortunes in the dye and textile business, and this allowed him to pursue and fund his many grand scientific undertakings throughout his life. Joseph Vallot received a classical education in Paris, first at the [[Lycée Charlemagne]] and then the [[Sorbonne]].<ref name="Qui">{{Cite book|url=http://archive.org/details/quitesvousannua00unkngoog|title=Qui êtes-vous? Annuaire des contemporains: notices biographiques|date=1924|publisher=La Librairie Delagrave|year=1924|editor-last=Ruffy|editor-first=G.|location=Paris|pages=741|language=French}}</ref><ref name="Richalet" /> He subsequently undertook studies at the Laboratoire de Recherche des Hautes Etudes, the [[Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle]] and at the [[École normale supérieure (Paris)|École Normale Supérieure]] in Paris.<ref name="Richalet" /> His interests were initially mostly in botany and geology, and he wrote articles on the plants of Africa and of the Pyrenees, publishing many alpine articles after 1886 in the annals of the French Alpine Club, of which he was a member of the Paris section.<ref name="Richalet" /><ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|year=1886|title=Membres Donateurs|url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9797626g/f752.image.r=Vallot|journal=Annuaire du Club Alpin Français|pages=724}}</ref> He later became the vice-president of the [[Société botanique de France]].<ref name="Mariani">{{Cite book|last=Mariani|first=Angelo |url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k2059911/f257.item|title=Figures contemporaines, tirées de l'album Mariani.... |publisher=Librarie Henry Floury|year=1908|volume=11|location=Paris|language=FR}}</ref> |

||

Vallot first visited Chamonix around 1877 and became fascinated with the glaciated mountains of the [[Mont Blanc massif]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Richalet|first=Jean-Paul|date=March 2001|title=The Scientific Observatories on Mont Blanc|url=http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/152702901750067936|journal=High Altitude Medicine & Biology|language=en|volume=2|issue=1|pages=57–68|doi=10.1089/152702901750067936|issn=1527-0297}}</ref> In 1880, he married the climber and [[Speleology|speleologist]], [[Gabrielle Vallot|Gabrielle Pérou.]]<ref>{{Cite web|title=Gabrielle Vallot|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/items/gabrielle-vallot/|url-status=live|access-date=2022-01-07|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=Fr}}</ref> They had three children: two sons, André and René, and a daughter, Madeleine. She became an alpinist herself; married the painter {{ill|Paul-Franz Namur|fr|Paul-Franz Namur}} and went on to gain a female record for the ascent Mont Blanc in 1920.<ref name="Qui" /><ref>{{Cite web|title=Ascension du mont Blanc par Madeleine Namur-Vallot|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/fr/items/ascension-du-mont-blanc-par-madeleine-namur-vallot/|url-status=live|access-date=2022-01-05|website=Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref> Both he and his wife typically wore [[Pith helmet|pith helmets]] in the mountains. |

Vallot first visited Chamonix around 1877 and became fascinated with the glaciated mountains of the [[Mont Blanc massif]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Richalet|first=Jean-Paul|date=March 2001|title=The Scientific Observatories on Mont Blanc|url=http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/152702901750067936|journal=High Altitude Medicine & Biology|language=en|volume=2|issue=1|pages=57–68|doi=10.1089/152702901750067936|pmid=11252700|issn=1527-0297}}</ref> In 1880, he married the climber and [[Speleology|speleologist]], [[Gabrielle Vallot|Gabrielle Pérou.]]<ref>{{Cite web|title=Gabrielle Vallot|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/items/gabrielle-vallot/|url-status=live|access-date=2022-01-07|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=Fr}}</ref> They had three children: two sons, André and René, and a daughter, Madeleine. She became an alpinist herself; married the painter {{ill|Paul-Franz Namur|fr|Paul-Franz Namur}} and went on to gain a female record for the ascent Mont Blanc in 1920.<ref name="Qui" /><ref>{{Cite web|title=Ascension du mont Blanc par Madeleine Namur-Vallot|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/fr/items/ascension-du-mont-blanc-par-madeleine-namur-vallot/|url-status=live|access-date=2022-01-05|website=Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref> Both he and his wife typically wore [[Pith helmet|pith helmets]] in the mountains. |

||

Vallot's initial interests were to follow his training as a botanist. Between 1881 and 1889 he published a range of botanical articles in various journals. These included monographs on the flora around [[Fontainebleau|Fontainebleu]]; the plants found in the pavements of Paris; the plants of [[Corsica]]; the flora of [[Senegal]] as well as the vegetation of the [[Pyrenees]]. It was to compare the vegetation between the Pyrenees and the Alps that Joseph Vallot came to Chamonix.<!-- A date of 1875 for his arrival in Chamonix is given in the obituary by Bregeault, and it seems possible that one or two dates given therein may not be wholly correct, as other sources give a slightly later date for his first visit to Chamonix (1887). Needs further work to compare his published botanical papers to be certain. --> with the [[Société géologique de France]].<ref name= "Bregeault Obituary">{{Cite journal|last=Bregeault|first=Henry|date=1926|title=Joseph Vallot (1854-1925)|url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k98090758/f109.item|journal=La Montagne: |

Vallot's initial interests were to follow his training as a botanist. Between 1881 and 1889 he published a range of botanical articles in various journals. These included monographs on the flora around [[Fontainebleau|Fontainebleu]]; the plants found in the pavements of Paris; the plants of [[Corsica]]; the flora of [[Senegal]] as well as the vegetation of the [[Pyrenees]]. It was to compare the vegetation between the Pyrenees and the Alps that Joseph Vallot came to Chamonix.<!-- A date of 1875 for his arrival in Chamonix is given in the obituary by Bregeault, and it seems possible that one or two dates given therein may not be wholly correct, as other sources give a slightly later date for his first visit to Chamonix (1887). Needs further work to compare his published botanical papers to be certain. --> with the [[Société géologique de France]].<ref name= "Bregeault Obituary">{{Cite journal|last=Bregeault|first=Henry|date=1926|title=Joseph Vallot (1854-1925)|url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k98090758/f109.item|journal=La Montagne: Revue mensuelle de Club Alpin Français|volume=22|pages=64–78}}</ref> |

||

Fascinated by the mountains all around Chamonix, Vallot engaged guides to not only climb Mont Blanc, but also to undertake more difficult routes such as the [[Aiguille du Dru]], even collecting alpine plants at the same time.<ref name="Bregeault Obituary" /> In 1886 he made two ascents of Mont Blanc, but realised that daily arduous climbs with short stops at the summit were impracticable for serious scientific investigation. At that time it was not known if it were possible for a human to survive a night at such an extreme altitude. So Vallot determined to find out for himself.<ref name="Bregeault Obituary" /> |

Fascinated by the mountains all around Chamonix, Vallot engaged guides to not only climb Mont Blanc, but also to undertake more difficult routes such as the [[Aiguille du Dru]], even collecting alpine plants at the same time.<ref name="Bregeault Obituary" /> In 1886 he made two ascents of Mont Blanc, but realised that daily arduous climbs with short stops at the summit were impracticable for serious scientific investigation. At that time it was not known if it were possible for a human to survive a night at such an extreme altitude. So Vallot determined to find out for himself.<ref name="Bregeault Obituary" /> |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Joseph Vallot has been described as "one of the founding fathers of scientific research on Mont Blanc".<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Mont Blanc Observatory|url=https://creamontblanc.org/en/mont-blanc-observatory/|url-status=live|access-date=2022-01-07|website=creamontblanc.org|language=English}}</ref> He first scaled its summit in 1881 which triggered a life-long fascination with the {{Convert|4808|m|ft}}-high mountain and its environs. |

Joseph Vallot has been described as "one of the founding fathers of scientific research on Mont Blanc".<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Mont Blanc Observatory|url=https://creamontblanc.org/en/mont-blanc-observatory/|url-status=live|access-date=2022-01-07|website=creamontblanc.org|language=English}}</ref> He first scaled its summit in 1881 which triggered a life-long fascination with the {{Convert|4808|m|ft}}-high mountain and its environs. |

||

He settled in Chamonix and, in 1887, contrived to endure three nights encamped on its summit. Using porters, he transported {{Convert|250|kg|lb}} of food and equipment to the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref>{{Cite journal|date=10 May 1888|title=Three days on the summit of Mont Blanc|url=https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Nature/r5tFAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=joseph+vallot+mont+blanc+1887&pg=PA35|journal=Nature|volume=38|pages= |

He settled in Chamonix and, in 1887, contrived to endure three nights encamped on its summit. Using porters, he transported {{Convert|250|kg|lb}} of food and equipment to the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref>{{Cite journal|date=10 May 1888|title=Three days on the summit of Mont Blanc|url=https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Nature/r5tFAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=joseph+vallot+mont+blanc+1887&pg=PA35|journal=Nature|volume=38|issue=967|pages=35–38|doi=10.1038/038035a0|s2cid=4078833}}</ref> Whilst most returned to the valley, just Vallot, two guides, plus the maker of his scientific equipment, F-M Richard, remained. They faced "great physical strain and constant self-denial" whilst making detailed and simultaneous scientific measurements at three different altitudes.<ref name="Hansen">{{Cite book|last=Hansen|first=Peter H.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mZU3CUZJN9sC&pg=PA215|title=The Summits of Modern Man|publisher=Harvard University Press|year=2013|isbn=978-0-674-07452-1|pages=215|language=en}}</ref> He involved his cousin, the engineer {{Interlanguage link|Henri Vallot|lt=Henri Vallot|fr}}, who assisted him by taking measurements in the Chamonix valley, with a further set of readings being made half way up the mountain in the [[Grands Mulets Hut]], whilst Vallot's group was encamped on Mont Blanc's ice-clad summit. After three days and nights of gruelling headaches, lack of appetite and terrible headaches due the altitude - all the time taking scientific measurements - Vallot and his party returned to Chamonix. They they were greeted by a deputation of flag-waving guides and received a rapturous welcome from the town's inhabitants who had decorated the town hall with flowers and erected a triumphal arch of flowers. A brass band led them through the streets to cheering, and they were met and congratulated on their achievement by the major, the municipal council, chief justice and many others. In his detailed published account of their undertaking, Vallot commented (in French) that ''"Astonished and confused by such a triumph, we begin to realise that by going to do scientific research at this altitude we have, without knowing it, achieved a mountaineering feat."''<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Vallot|first=Joseph|date=1 January 1887|title=Trois jours au Mont Blanc: cinq ascensions au sommet|url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9689758w/f50.item.r=Vallot|journal=Annuaire du Club Alpin Français|pages=38}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|date=12 October 1887|title=On Mont Blanc|page=3|work=Washington Evening Star|url=https://www.gastearsivi.com/gazete/evening_star/1887-10-12/3|access-date=13 January 2022}}</ref><!-- Washington Post newspaper stated" ..at 7pm, Chamounix was reached, and the whole population of the town, headed by the maire (mayor), received the successful climbers with gifts of flowers and congratulations at having been the first to accomplish such an expedition" --> |

||

Recognising the impracticalities of doing scientific studies on Mont Blanc without a permanent base, Vallot subsequently engaged his cousin Henri to draw up plans to build a high altitude observation station which he funded himself.<ref name="Henri Vallot">{{Cite web|title=Henri Vallot (1876): Ingénieur, géodésien et topographe|url=http://archives-histoire.centraliens.net/pdfs/revues/rev642.pdf|url-status=live|access-date=10 January 2022|website=Centrale Supélec Alumni|language=fr}}</ref> Vallot decided to construct two observatories at different altitudes. His 'Mont Blanc Observatory' was built in Chamonix itself where it served as a base station for invited scientists, whilst the 'Observatoire Vallot' was positioned on a shoulder below Mont Blanc's summit, which enabled comparison of physical measurements made in the valley with those made at high altitude.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|title=Our story {{!}} CREA Mont-Blanc|url=https://creamontblanc.org/en/our-story/|access-date=2022-01-07|website=creamontblanc.org|language=English}}</ref> |

Recognising the impracticalities of doing scientific studies on Mont Blanc without a permanent base, Vallot subsequently engaged his cousin Henri to draw up plans to build a high altitude observation station which he funded himself.<ref name="Henri Vallot">{{Cite web|title=Henri Vallot (1876): Ingénieur, géodésien et topographe|url=http://archives-histoire.centraliens.net/pdfs/revues/rev642.pdf|url-status=live|access-date=10 January 2022|website=Centrale Supélec Alumni|language=fr}}</ref> Vallot decided to construct two observatories at different altitudes. His 'Mont Blanc Observatory' was built in Chamonix itself where it served as a base station for invited scientists, whilst the 'Observatoire Vallot' was positioned on a shoulder below Mont Blanc's summit, which enabled comparison of physical measurements made in the valley with those made at high altitude.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|title=Our story {{!}} CREA Mont-Blanc|url=https://creamontblanc.org/en/our-story/|access-date=2022-01-07|website=creamontblanc.org|language=English}}</ref> |

||

In the summer of 1890, and with support from the Commune, Vallot employed110 porters to carry building materials to construct his observatory on a rocky shoulder below the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref name="High Life">{{Cite book|last=West|first=John B.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o0rhBwAAQBAJ |

In the summer of 1890, and with support from the Commune, Vallot employed110 porters to carry building materials to construct his observatory on a rocky shoulder below the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref name="High Life">{{Cite book|last=West|first=John B.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o0rhBwAAQBAJ&dq=%22joseph+vallot%22+three+nights+summit&pg=PA372|title=High Life: A History of High-Altitude Physiology and Medicine|publisher=Springer|year=2013|isbn=978-1-4614-7573-6|pages=76–78|language=en}}</ref><ref name="Tutton" /> It was positioned on the Rochers des Bosses at a height of {{Convert|4358|m|ft}}, but was relocated eight years later to a more suitable point nearby at {{Convert|4350|m|ft}}. In 1892 he also arranged for the construction of a separate cabin for climbers who had previously been accommodated in the main observatory building.<ref name="Henri Vallot" /> |

||

Vallot acted as the observatory's director for over 30 years. He and the many scientists he invited to study there made numerous observations across many disciplines, including astronomy, botany, cartography, geology, glaciology, medicine, meteorology and physiology. The results of these researches were published between 1893 and 1917 in seven volumes of the ''Annales de l'Observatoire du Mont Blanc'', as well as in the ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences.''<ref name="Richalet">{{Cite journal|last=Richalet|first=Jean-Paul|date=2001-03-01|title=The Scientific Observatories on Mont Blanc|url=https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/152702901750067936|journal=High Altitude Medicine & Biology|volume=2|issue=1|pages=57–68|doi=10.1089/152702901750067936}}</ref> |

Vallot acted as the observatory's director for over 30 years. He and the many scientists he invited to study there made numerous observations across many disciplines, including astronomy, botany, cartography, geology, glaciology, medicine, meteorology and physiology. The results of these researches were published between 1893 and 1917 in seven volumes of the ''Annales de l'Observatoire du Mont Blanc'', as well as in the ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences.''<ref name="Richalet">{{Cite journal|last=Richalet|first=Jean-Paul|date=2001-03-01|title=The Scientific Observatories on Mont Blanc|url=https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/152702901750067936|journal=High Altitude Medicine & Biology|volume=2|issue=1|pages=57–68|doi=10.1089/152702901750067936|pmid=11252700}}</ref> |

||

The first recorded case of [[High-altitude pulmonary edema|pulmonary oedema]] directly attributable to the effects of high [[altitude]] (as documented by an [[autopsy]]) occurred in Vallot's observatory in 1891, with the death of a Dr. Jacottet. In 1913, Vallot became the first person to publish research demonstrating the deterioration in physical performance with increasing altitude; he used squirrels as his study animals.<ref name="Richalet" /> |

The first recorded case of [[High-altitude pulmonary edema|pulmonary oedema]] directly attributable to the effects of high [[altitude]] (as documented by an [[autopsy]]) occurred in Vallot's observatory in 1891, with the death of a Dr. Jacottet. In 1913, Vallot became the first person to publish research demonstrating the deterioration in physical performance with increasing altitude; he used squirrels as his study animals.<ref name="Richalet" /> |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

== Other achievements == |

== Other achievements == |

||

In the 1890s, Vallot was the first person to make very detailed topographic measurements of the [[ablation zone]] of the [[Mer de Glace]] - largest [[glacier]] in the Mont Blanc massif and, indeed, in France.* <ref name="MerdeGlace" /><ref>{{Cite journal| |

In the 1890s, Vallot was the first person to make very detailed topographic measurements of the [[ablation zone]] of the [[Mer de Glace]] - largest [[glacier]] in the Mont Blanc massif and, indeed, in France.* <ref name="MerdeGlace" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Mourey|first1=Jacques|last2=Ravanel|first2=Ludovic|date=2017-01-01|title=Evolution of Access Routes to High Mountain Refuges of the Mer de Glace Basin (Mont Blanc Massif, France)|url=https://journals.openedition.org/rga/3790|journal=Journal of Alpine Research {{!}} Revue de géographie alpine|language=en|issue=105–4|doi=10.4000/rga.3790|issn=0035-1121}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Vincent|first1=C.|last2=Harter|first2=M.|last3=Gilbert|first3=A.|last4=Berthier|first4=E.|last5=Six|first5=D.|date=2014|title=Future fluctuations of Mer de Glace, French Alps, assessed using a parameterized model calibrated with past thickness changes|url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0260305500258096/type/journal_article|journal=Annals of Glaciology|language=en|volume=55|issue=66|pages=15–24|doi=10.3189/2014AoG66A050|s2cid=32907464|issn=0260-3055}}</ref> |

||

In 1899 he and his cousin, Henri Vallot, lent their formal support to a proposal to construct an underground railway tunnel from the town of [[Les Houches]] to just a few hundred metres below the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref>{{Cite book| |

In 1899 he and his cousin, Henri Vallot, lent their formal support to a proposal to construct an underground railway tunnel from the town of [[Les Houches]] to just a few hundred metres below the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Vallot|first1=Joseph|url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1421419g|title=Chemin de fer des Houches au sommet du Mont-Blanc : projet Saturnin Fabre, études préliminaires et avant-projet|last2=Vallot|first2=Henri|date=1899|location=Paris|language=EN}}</ref> |

||

== Honours and awards == |

== Honours and awards == |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

== Later life == |

== Later life == |

||

[[File:Joseph Vallot 1920.png|left|thumb|Joseph Vallot in 1920 on his final visit to the observatory he built.<ref name="Tutton">{{Cite journal|last=Tutton|first=A.E.H.|date=23 May 1925|title=The Story of the Mont Blanc Observatories.|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/115803a0.pdf|journal=Nature|volume=115|pages= |

[[File:Joseph Vallot 1920.png|left|thumb|Joseph Vallot in 1920 on his final visit to the observatory he built.<ref name="Tutton">{{Cite journal|last=Tutton|first=A.E.H.|date=23 May 1925|title=The Story of the Mont Blanc Observatories.|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/115803a0.pdf|journal=Nature|volume=115|issue=2899|pages=803–805|doi=10.1038/115803a0|s2cid=4102298}}</ref>]] |

||

From 1905 onwards, with his health deteriorating from the many long stays at high altitude, Joseph Vallot started to spend his winter months in Nice. The climate was more favourable for him there, though he was no less active. In Nice he built a weather station to enable him to study the region's weather, and he also continued with his botanical interests. According to the website of the Alpin Museum in Chamonix, Vallot collected some 200,000 herbarium specimens which were donated to the [[Muséum d'histoire naturelle de Nice|Nice museum]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Joseph Vallot dans un avion|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/items/joseph-vallot-dans-un-avion/|access-date=2022-01-09|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

From 1905 onwards, with his health deteriorating from the many long stays at high altitude, Joseph Vallot started to spend his winter months in Nice. The climate was more favourable for him there, though he was no less active. In Nice he built a weather station to enable him to study the region's weather, and he also continued with his botanical interests. According to the website of the Alpin Museum in Chamonix, Vallot collected some 200,000 herbarium specimens which were donated to the [[Muséum d'histoire naturelle de Nice|Nice museum]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Joseph Vallot dans un avion|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/items/joseph-vallot-dans-un-avion/|access-date=2022-01-09|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

In September 1920, at the age of 66, Vallot made his last climb to stay and to make scientific measurements in his high altitude observatory. From there he also made his 34th and final ascent to the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Joseph Vallot travaillant sur la terrasse de l'Observatoire.|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/fr/items/joseph-vallot-travaillant-sur-la-terrasse-de-lobservatoire/|access-date=2022-01-09|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Monsieur Joseph Vallot, directeur des Observatoires du Mont-Blanc, terminant ses expériences d'actinométrie. Observatoire des Bosses, 7 septembre 1920|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/fr/items/monsieur-joseph-vallot-directeur-des-observatoires-du-mont-blanc-terminant-ses-experiences-dactinometrie-observatoire-des-bosses-7-septembre-1920/|access-date=2022-01-09|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

In September 1920, at the age of 66, Vallot made his last climb to stay and to make scientific measurements in his high altitude observatory. From there he also made his 34th and final ascent to the summit of Mont Blanc.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Joseph Vallot travaillant sur la terrasse de l'Observatoire.|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/fr/items/joseph-vallot-travaillant-sur-la-terrasse-de-lobservatoire/|access-date=2022-01-09|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Monsieur Joseph Vallot, directeur des Observatoires du Mont-Blanc, terminant ses expériences d'actinométrie. Observatoire des Bosses, 7 septembre 1920|url=https://www.mountainmuseums.org/fr/items/monsieur-joseph-vallot-directeur-des-observatoires-du-mont-blanc-terminant-ses-experiences-dactinometrie-observatoire-des-bosses-7-septembre-1920/|access-date=2022-01-09|website=IALP Mountain Museums|language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

||

When his health started to deteriorate further, Vallot left Chamonix and moved to his villa in [[Nice]] where, after a long illness, he eventually died on 11 April 1925.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Helbronner|first=Association Paul|date=2011-10-28|title=Joseph Vallot|url=http://www.helbronner.org/article.php3?id_article=19|access-date=2022-01-06|website=www.helbronner.org|language=fr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|date=1925|title=Joseph Vallot|url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9765131m/f214.item.texteImage#|journal=La Montagne : |

When his health started to deteriorate further, Vallot left Chamonix and moved to his villa in [[Nice]] where, after a long illness, he eventually died on 11 April 1925.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Helbronner|first=Association Paul|date=2011-10-28|title=Joseph Vallot|url=http://www.helbronner.org/article.php3?id_article=19|access-date=2022-01-06|website=www.helbronner.org|language=fr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|date=1925|title=Joseph Vallot|url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9765131m/f214.item.texteImage#|journal=La Montagne : Revue mensuelle du Club alpin français|pages=172–174}}</ref> His body is interred at [[Père Lachaise Cemetery]] in Paris. In his [[Will and testament|will]], Vallot's left his observatory to the French nation and it has since been the utilised by the [[Paris Observatory]], the [[French National Centre for Scientific Research]] (CNRS) and, more recently, the {{Interlanguage link|Research Center for Alpine Ecosystems|fr|Centre de recherches sur les écosystèmes d'altitude}} (CREA Mont-Blanc).<ref name=":0" /> |

||

{{clear}} |

{{clear}} |

||

== Selected publications == |

== Selected publications == |

||

Revision as of 20:26, 17 January 2022

Joseph Vallot | |

|---|---|

Vallot in 1892 | |

| Born | 16 February 1854 |

| Died | 11 April 1925 |

| Burial place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Scientific research on Mont Blanc; construction of observatory and mountain refuge |

| Children | 3 |

| Honours | Legion of Honour |

Joseph Vallot (1854-1925) was a French scientist, astronomer, botanist, geographer, cartographer and alpinist and "one of the founding fathers of scientific research on Mont Blanc". He is known mainly for his fascination with Mont Blanc and his work in funding and constructing a high altitude observatory below its summit, and for the many years of study and research work that he and his wife conducted both there, and at their base in Chamonix. The observatory and adjacent refuge that he constructed for use by mountain guides and their clients attempting Mont Blanc summit both still bears his name today, despite being rebuilt in modern times.

He received many awards for his scientific achievements, including France's highest order of merit, the Legion d'honeur.

Life

Joseph Vallot was born on 16 February 1854 at Lodève in southern France. His father was Émile Vallot and he had a cousin, Henri - both of whom Joseph collaborated professionally with in later life.[1]. Vallot's family were wealthy, having made their fortunes in the dye and textile business, and this allowed him to pursue and fund his many grand scientific undertakings throughout his life. Joseph Vallot received a classical education in Paris, first at the Lycée Charlemagne and then the Sorbonne.[2][3] He subsequently undertook studies at the Laboratoire de Recherche des Hautes Etudes, the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle and at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris.[3] His interests were initially mostly in botany and geology, and he wrote articles on the plants of Africa and of the Pyrenees, publishing many alpine articles after 1886 in the annals of the French Alpine Club, of which he was a member of the Paris section.[3][4] He later became the vice-president of the Société botanique de France.[5]

Vallot first visited Chamonix around 1877 and became fascinated with the glaciated mountains of the Mont Blanc massif.[6] In 1880, he married the climber and speleologist, Gabrielle Pérou.[7] They had three children: two sons, André and René, and a daughter, Madeleine. She became an alpinist herself; married the painter Paul-Franz Namur and went on to gain a female record for the ascent Mont Blanc in 1920.[2][8] Both he and his wife typically wore pith helmets in the mountains.

Vallot's initial interests were to follow his training as a botanist. Between 1881 and 1889 he published a range of botanical articles in various journals. These included monographs on the flora around Fontainebleu; the plants found in the pavements of Paris; the plants of Corsica; the flora of Senegal as well as the vegetation of the Pyrenees. It was to compare the vegetation between the Pyrenees and the Alps that Joseph Vallot came to Chamonix. with the Société géologique de France.[9]

Fascinated by the mountains all around Chamonix, Vallot engaged guides to not only climb Mont Blanc, but also to undertake more difficult routes such as the Aiguille du Dru, even collecting alpine plants at the same time.[9] In 1886 he made two ascents of Mont Blanc, but realised that daily arduous climbs with short stops at the summit were impracticable for serious scientific investigation. At that time it was not known if it were possible for a human to survive a night at such an extreme altitude. So Vallot determined to find out for himself.[9]

Mont Blanc Observatories

Joseph Vallot has been described as "one of the founding fathers of scientific research on Mont Blanc".[10] He first scaled its summit in 1881 which triggered a life-long fascination with the 4,808 metres (15,774 ft)-high mountain and its environs.

He settled in Chamonix and, in 1887, contrived to endure three nights encamped on its summit. Using porters, he transported 250 kilograms (550 lb) of food and equipment to the summit of Mont Blanc.[11] Whilst most returned to the valley, just Vallot, two guides, plus the maker of his scientific equipment, F-M Richard, remained. They faced "great physical strain and constant self-denial" whilst making detailed and simultaneous scientific measurements at three different altitudes.[12] He involved his cousin, the engineer Henri Vallot, who assisted him by taking measurements in the Chamonix valley, with a further set of readings being made half way up the mountain in the Grands Mulets Hut, whilst Vallot's group was encamped on Mont Blanc's ice-clad summit. After three days and nights of gruelling headaches, lack of appetite and terrible headaches due the altitude - all the time taking scientific measurements - Vallot and his party returned to Chamonix. They they were greeted by a deputation of flag-waving guides and received a rapturous welcome from the town's inhabitants who had decorated the town hall with flowers and erected a triumphal arch of flowers. A brass band led them through the streets to cheering, and they were met and congratulated on their achievement by the major, the municipal council, chief justice and many others. In his detailed published account of their undertaking, Vallot commented (in French) that "Astonished and confused by such a triumph, we begin to realise that by going to do scientific research at this altitude we have, without knowing it, achieved a mountaineering feat."[13][14]

Recognising the impracticalities of doing scientific studies on Mont Blanc without a permanent base, Vallot subsequently engaged his cousin Henri to draw up plans to build a high altitude observation station which he funded himself.[15] Vallot decided to construct two observatories at different altitudes. His 'Mont Blanc Observatory' was built in Chamonix itself where it served as a base station for invited scientists, whilst the 'Observatoire Vallot' was positioned on a shoulder below Mont Blanc's summit, which enabled comparison of physical measurements made in the valley with those made at high altitude.[16]

In the summer of 1890, and with support from the Commune, Vallot employed110 porters to carry building materials to construct his observatory on a rocky shoulder below the summit of Mont Blanc.[17][18] It was positioned on the Rochers des Bosses at a height of 4,358 metres (14,298 ft), but was relocated eight years later to a more suitable point nearby at 4,350 metres (14,270 ft). In 1892 he also arranged for the construction of a separate cabin for climbers who had previously been accommodated in the main observatory building.[15]

Vallot acted as the observatory's director for over 30 years. He and the many scientists he invited to study there made numerous observations across many disciplines, including astronomy, botany, cartography, geology, glaciology, medicine, meteorology and physiology. The results of these researches were published between 1893 and 1917 in seven volumes of the Annales de l'Observatoire du Mont Blanc, as well as in the Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences.[3]

The first recorded case of pulmonary oedema directly attributable to the effects of high altitude (as documented by an autopsy) occurred in Vallot's observatory in 1891, with the death of a Dr. Jacottet. In 1913, Vallot became the first person to publish research demonstrating the deterioration in physical performance with increasing altitude; he used squirrels as his study animals.[3]

Covering an area of 60 square metres, the Observatoire Vallot included a laboratory, a kitchen and an extravagantly-decorated room known as the 'Chinese Salon' which Vallot elaborately adorned with Asian items, including large tapestries, Persian rugs, a Samurai helmet and innumerable exotic ornaments. His observatory and nearby refuge attracted scientists as well as adventurers such as Achille Ratti (the future Pope Pius XI).[19]

Vallot put his knowledge and his own observatory at the disposal of the French astronomer, Pierre Janssen, when the latter initiated plans to construct his own observatory on the ice-capped summit of Mont Blanc. Because of his knowledge of glaciers and the movement of ice, Vallot strongly advised against it. The project went ahead nevertheless, but was only able to operate for a short period of time before the wooden structure began to sink into Mont Blanc's summit ice-cap. It was eventually dismantled and the timber used as firewood in Vallot's own observatory for many years. [citation needed]

In 1984, and as part of a plan to upgrade and return the observatory back into active use for high-altitude scientific research,[20] Vallot’s Chinese salon was dismantled and reassembled in the Alpine Museum in Chamonix.[21][22]

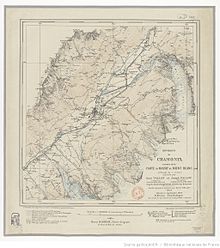

Cartography

For some thirty years, Joseph Vallot worked alongside his cousin Henri in the latter's ambitious project to survey and create a new, detailed map of the Mont Blanc massif at a scale of 1;20000. Joseph did the high mountain survey and photography, whilst Henri surveyed at lower altitudes. Only one map was published within their lifetimes. This covered the northern slopes of Mont Blanc down to Chamonix; the remainder of the work was published by Henri's son, Charles.[15][23] Vallot received a diploma from the Société de Topographie de France for his contribution to his cousin's work [24]

Other achievements

In the 1890s, Vallot was the first person to make very detailed topographic measurements of the ablation zone of the Mer de Glace - largest glacier in the Mont Blanc massif and, indeed, in France.* [1][25][26]

In 1899 he and his cousin, Henri Vallot, lent their formal support to a proposal to construct an underground railway tunnel from the town of Les Houches to just a few hundred metres below the summit of Mont Blanc.[27]

Honours and awards

Joseph Vallot's contributions to cartography and to high altitude science (many made jointly with his wife) led to him receiving many honours and accolades over his lifetime.

In 1895 Vallot was awarded a gold medal from the Société d'Encouragement for his work in establishing the Mont Blanc Observatory.[2][28]

He was also awarded the 'grand prix des sciences physiques' and the 'prix Wilde' of the French Academy of Sciences. He was a recipient of the Legion of Honour; made a Chevalier of the Ordre des Saints-Maurice-et-Lazare, an officer of the Order of the Medjidie, and an officer of the Order of Saint-Charles of Monaco. In addition, Vallot was a corresponding member of the Bureau des Longitudes and was granted honorary presidency of the French Alpine Club.[2]

Places named in his honour include Avenue Joseph Vallot and Lycée Joseph-Vallot in Lodève,[29] Rue Joseph Vallot, Chamonix[30], Rue Joseph Vallot and Avenue Joseph Vallot, Nice.[31]

Later life

From 1905 onwards, with his health deteriorating from the many long stays at high altitude, Joseph Vallot started to spend his winter months in Nice. The climate was more favourable for him there, though he was no less active. In Nice he built a weather station to enable him to study the region's weather, and he also continued with his botanical interests. According to the website of the Alpin Museum in Chamonix, Vallot collected some 200,000 herbarium specimens which were donated to the Nice museum.[32]

In 1907, Vallot, who had partnered with the cinematographer, Léon Gaumont,[33] was involved in the production of a 9.5mm film documenting the climbing of Mont Blanc.[34]

In September 1920, at the age of 66, Vallot made his last climb to stay and to make scientific measurements in his high altitude observatory. From there he also made his 34th and final ascent to the summit of Mont Blanc.[35][36]

When his health started to deteriorate further, Vallot left Chamonix and moved to his villa in Nice where, after a long illness, he eventually died on 11 April 1925.[37][38] His body is interred at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. In his will, Vallot's left his observatory to the French nation and it has since been the utilised by the Paris Observatory, the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and, more recently, the Research Center for Alpine Ecosystems (CREA Mont-Blanc).[16]

Selected publications

- Vallot (1887) Trois jours au Mont Blanc: Cinq ascensions au sommet. Annuaire du Club Alpin Français, pp11-40.

- Etudes Sur La Flore Du Sénégal

- Joseph Vallot (1882) Etudes Sur La Flore Du Sénégal, Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France, 29:5, 168-171

- Vallot, H. & Vallot, J. (1906) Carte du massif du Mont Blanc

- Vallot J (1900) Annales de l’observatoire météorologique, physique et glaciaire du Mont Blanc. Tome 4. Steinheil, Paris, 189 pp

- Vallot J (1905) Annales de l'Observatoire météorologique, physique et glaciaire du Mont Blanc Tome VI

Further reading

- Vivian, R. (1986) L'épopée Vallot au Mont Blanc, ISBN 9782207232514

- Vivian, R. (2005) Les glaciers du Mont-Blanc, La Fontaine de Siloé, ISBN 2-84206285X

See also

References

- ^ a b Vallot, J. (1898). "Exploration des moulins de la mer de glace: Forage de M. Émile Vallot". In Steinheil, G. (ed.). Annales de l'Observatoire météorologique physique et glaciaire du Mont-Blanc (in French). Vol. 3. Paris. pp. 190–193.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Ruffy, G., ed. (1924). Qui êtes-vous? Annuaire des contemporains: notices biographiques (in French). Paris: La Librairie Delagrave. p. 741.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e Richalet, Jean-Paul (2001-03-01). "The Scientific Observatories on Mont Blanc". High Altitude Medicine & Biology. 2 (1): 57–68. doi:10.1089/152702901750067936. PMID 11252700.

- ^ "Membres Donateurs". Annuaire du Club Alpin Français: 724. 1886.

- ^ Mariani, Angelo (1908). Figures contemporaines, tirées de l'album Mariani... (in French). Vol. 11. Paris: Librarie Henry Floury.

- ^ Richalet, Jean-Paul (March 2001). "The Scientific Observatories on Mont Blanc". High Altitude Medicine & Biology. 2 (1): 57–68. doi:10.1089/152702901750067936. ISSN 1527-0297. PMID 11252700.

- ^ "Gabrielle Vallot". IALP Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Ascension du mont Blanc par Madeleine Namur-Vallot". Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Bregeault, Henry (1926). "Joseph Vallot (1854-1925)". La Montagne: Revue mensuelle de Club Alpin Français. 22: 64–78.

- ^ "The Mont Blanc Observatory". creamontblanc.org. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Three days on the summit of Mont Blanc". Nature. 38 (967): 35–38. 10 May 1888. doi:10.1038/038035a0. S2CID 4078833.

- ^ Hansen, Peter H. (2013). The Summits of Modern Man. Harvard University Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-674-07452-1.

- ^ Vallot, Joseph (1 January 1887). "Trois jours au Mont Blanc: cinq ascensions au sommet". Annuaire du Club Alpin Français: 38.

- ^ "On Mont Blanc". Washington Evening Star. 12 October 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b c "Henri Vallot (1876): Ingénieur, géodésien et topographe" (PDF). Centrale Supélec Alumni (in French). Retrieved 10 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Our story | CREA Mont-Blanc". creamontblanc.org. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ^ West, John B. (2013). High Life: A History of High-Altitude Physiology and Medicine. Springer. pp. 76–78. ISBN 978-1-4614-7573-6.

- ^ a b Tutton, A.E.H. (23 May 1925). "The Story of the Mont Blanc Observatories" (PDF). Nature. 115 (2899): 803–805. doi:10.1038/115803a0. S2CID 4102298.

- ^ Grirfiths, Rhys (14 November 2016). "Joseph Vallot's Chinese Salon". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Observatoire Vallot". www.arpealtitude.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Griffiths, Rhys (14 Nov 2016). "Joseph Vallot's Chinese Salon | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Todd, Andrew (2015-10-21). "Eco-friendly architecture in the Alps hits new heights". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Etat d'avancement des opérations de la carte du massif du Mont-Blanc de MM. Henri et Joseph Vallot à l'échelle du 20.000e". IALP Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ "Diplôme de membre de la société de Topographie de France délivré à Joseph Vallot". IALP Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ Mourey, Jacques; Ravanel, Ludovic (2017-01-01). "Evolution of Access Routes to High Mountain Refuges of the Mer de Glace Basin (Mont Blanc Massif, France)". Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine (105–4). doi:10.4000/rga.3790. ISSN 0035-1121.

- ^ Vincent, C.; Harter, M.; Gilbert, A.; Berthier, E.; Six, D. (2014). "Future fluctuations of Mer de Glace, French Alps, assessed using a parameterized model calibrated with past thickness changes". Annals of Glaciology. 55 (66): 15–24. doi:10.3189/2014AoG66A050. ISSN 0260-3055. S2CID 32907464.

- ^ Vallot, Joseph; Vallot, Henri (1899). Chemin de fer des Houches au sommet du Mont-Blanc : projet Saturnin Fabre, études préliminaires et avant-projet. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Diplôme de médaille d'or décerné à M. Vallot – Observatoire météorologique du Mont Blanc". IALP Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ "Comprehensive School Joseph Vallot · Rue Dr Henri Mas, 34700 Lodève, France". Comprehensive School Joseph Vallot · Rue Dr Henri Mas, 34700 Lodève, France. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "Rue Joseph Vallot · 74400 Chamonix, France". Rue Joseph Vallot · 74400 Chamonix, France. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "Rue Joseph Vallot · 06100 Nice, France". Rue Joseph Vallot · 06100 Nice, France. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "Joseph Vallot dans un avion". IALP Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ Jean-Jacques, Meusy. "Léon Gaumont". FranceArchives (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ Moules, Patrick (2020). The 9.5mm vintage film encyclopaedia. Kibworth Beauchamp. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-83859-269-1. OCLC 1224499984.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Joseph Vallot travaillant sur la terrasse de l'Observatoire". IALP Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ "Monsieur Joseph Vallot, directeur des Observatoires du Mont-Blanc, terminant ses expériences d'actinométrie. Observatoire des Bosses, 7 septembre 1920". IALP Mountain Museums (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ Helbronner, Association Paul (2011-10-28). "Joseph Vallot". www.helbronner.org (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ "Joseph Vallot". La Montagne : Revue mensuelle du Club alpin français: 172–174. 1925.

External links

- List of botanical publications by Joseph Vallot in Taxonomic literature : a selective guide to botanical publications Vol VI, 1986

- Numerous photographs of Joseph Vallot (search results from mountainmuseum.org)