Guam kingfisher: Difference between revisions

Add: url, pages, issue, volume, journal, title, jstor, bibcode, year, s2cid, authors 1-2. Removed proxy/dead URL that duplicated identifier. Removed parameters. Formatted dashes. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this tool. Report bugs. | #UCB_Gadget |

→References: | Add: pages, volume, journal, year, title, authors 1-2. Formatted dashes. | Use this tool. Report bugs. | #UCB_Gadget | Add: page, issn, url, s2cid, doi, pages, issue, volume, year, journal, title, authors 1-2. | Use this tool. Report bugs. | #UCB_Gadget |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

* |

*{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.biocon.2012.05.016|title=A Bayesian network approach for selecting translocation sites for endangered island birds |year=2012 |last1=Laws |first1=Rebecca J. |last2=Kesler |first2=Dylan C. |journal=Biological Conservation |volume=155 |pages=178–185 }} |

||

*Kesler, D.C., and S.M. Haig. 2007. "Conservation biology for suites of species: demographic modeling for the Pacific island kingfishers." Biological Conservation 136:520-530. |

*Kesler, D.C., and S.M. Haig. 2007. "Conservation biology for suites of species: demographic modeling for the Pacific island kingfishers." Biological Conservation 136:520-530. |

||

*{{cite journal|jstor=4495250|title=Multiscale Habitat Use and Selection in Cooperatively Breeding Micronesian Kingfishers |last1=Kesler |first1=Dylan C. |last2=Haig |first2=Susan M. |journal=The Journal of Wildlife Management |year=2007 |volume=71 |issue=3 |pages=765–772 |doi=10.2193/2006-011 |s2cid=4104260 |url=https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/684 }} |

|||

*Kesler, D.C., and S.M. Haig. 2007. "Multi-scale resource use and selection in cooperatively breeding Micronesian Kingfishers." Journal of Wildlife Management 71:765-772. |

|||

*{{cite journal |doi=10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[381:TPADIC]2.0.CO;2|issn=0004-8038 |year=2007 |volume=124 |page=381 |title=Territoriality, Prospecting, and Dispersal in Cooperatively Breeding Micronesian Kingfishers (Todiramphus Cinnamominus Reichenbachii) |last1=Kesler |first1=Dylan C. |last2=Haig |first2=Susan M. |journal=The Auk |issue=2 |s2cid=14032686 |url=https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/664 }} |

|||

*Kesler, D.C., and S.M. Haig. 2007. "Territoriality, prospecting, and dispersal in cooperatively breeding Micronesian Kingfishers." Auk 124:381-395. |

|||

*Kesler, D.C., and S. M. Haig. 2005. "Microclimate and nest site selection in Micronesian kingfishers." Pacific Science 59:499-508. |

*Kesler, D.C., and S. M. Haig. 2005. "Microclimate and nest site selection in Micronesian kingfishers." Pacific Science 59:499-508. |

||

*Kesler, D.C. 2006. ''Population demography, resource use, and movement in cooperatively breeding Micronesian Kingfishers''. Doctoral dissertation. Oregon State University. Corvallis, OR. |

*Kesler, D.C. 2006. ''Population demography, resource use, and movement in cooperatively breeding Micronesian Kingfishers''. Doctoral dissertation. Oregon State University. Corvallis, OR. |

||

Revision as of 11:46, 14 August 2022

| Guam kingfisher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Captive male at the Bronx Zoo. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Coraciiformes |

| Family: | Alcedinidae |

| Subfamily: | Halcyoninae |

| Genus: | Todiramphus |

| Species: | T. cinnamominus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Todiramphus cinnamominus (Swainson, 1821)

| |

The Guam kingfisher (Todiramphus cinnamominus) is a species of kingfisher from the United States Territory of Guam. It is restricted to a captive breeding program following its extinction in the wild due primarily to predation by the introduced brown tree snake.

Taxonomy and description

In the indigenous Chamorro language, it is referred to as sihek.[2]

The mysterious extinct Ryūkyū kingfisher, known from a single specimen, is sometimes placed as a subspecies (T. c. miyakoensis; Fry et al. 1992), but was declared invalid by the International Ornithological Congress in 2022, rendering the species monotypic.[3] Among-island differences in morphological, behavioral, and ecological characteristics have been determined sufficient that Micronesian kingfisher populations, of which the Guam kingfisher was considered a subspecies, should be split into separate species.[4]

This is a brilliantly colored, medium-sized kingfisher, 20–24 cm in length. They have iridescent blue backs and rusty-cinnamon heads. Adult male Guam kingfishers have cinnamon underparts while females and juveniles are white below. They have large laterally-flattened bills and dark legs. The calls of Micronesian kingfishers are generally raspy chattering.[5]

Behavior

Guam kingfishers were terrestrial forest generalists that tended to be somewhat secretive. The birds nested in cavities excavated from soft-wooded trees and arboreal termitaria, on Guam.[6] Micronesian kingfishers defended permanent territories as breeding pairs and family groups.[7] Both sexes care for young, and some offspring remain with parents for extended periods. Research suggests that thermal environment has the potential to influence reproduction.[7]

Conservation status

The Guam kingfisher population was extirpated from its native habitat after the introduction of brown tree snakes.[8] It was last seen in the wild in 1988, and the birds are now U.S. listed as endangered.[5] The Guam kingfisher persists as a captive population of fewer than two hundred individuals (as of 2017) in US mainland and Guam breeding facilities. However, there are plans to reintroduce the Guam birds to Palmyra Atoll by 2022, and potentially also back to their native range on Guam if protected areas can be established and the threat of the brown tree snakes is eliminated or better controlled.[2][5] Unfortunately, however, three decades of research and management has yielded little hope for safe habitats on Guam.[citation needed]

References

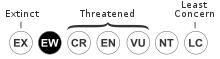

- ^ BirdLife International (2017). "Todiramphus cinnamominus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22725862A117372355. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22725862A117372355.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b Magazine, Smithsonian. "Scientists Are Using 3-D-Printing Technology to Ready Guam Kingfishers for Reintroduction to the Wild". www.smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ "IOC World Bird List 12.1". IOC World Bird List Datasets. doi:10.14344/ioc.ml.12.1. S2CID 246050277.

- ^ Andersen, Michael J.; Shult, Hannah T.; Cibois, Alice; Thibault, Jean-Claude; Filardi, Christopher E.; Moyle, Robert G. (2015). "Rapid diversification and secondary sympatry in Australo-Pacific kingfishers (Aves: Alcedinidae: Todiramphus)". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (2): 140375. Bibcode:2015RSOS....240375A. doi:10.1098/rsos.140375. PMC 4448819. PMID 26064600.

- ^ a b c "ECOS: Species Profile". ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ Marshall, Samuel D. (1989). "Nest Sites of the Micronesian Kingfisher on Guam". The Wilson Bulletin. 101 (3): 472–477. ISSN 0043-5643. JSTOR 4162756.

- ^ a b Kesler, Dylan C.; Lopes, Iara F.; Haig, Susan M. (March 2006). "Sex determination of Pohnpei Micronesian Kingfishers using morphological and molecular genetic techniques". Journal of Field Ornithology. 77 (2): 229–232. doi:10.1111/j.1557-9263.2006.00045.x. ISSN 0273-8570. S2CID 14034258.

- ^ Savidge, Julie A. (1987). "Extinction of an Island Forest Avifauna by an Introduced Snake". Ecology. 68 (3): 660–668. doi:10.2307/1938471. ISSN 0012-9658. JSTOR 1938471.

- Laws, Rebecca J.; Kesler, Dylan C. (2012). "A Bayesian network approach for selecting translocation sites for endangered island birds". Biological Conservation. 155: 178–185. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.05.016.

- Kesler, D.C., and S.M. Haig. 2007. "Conservation biology for suites of species: demographic modeling for the Pacific island kingfishers." Biological Conservation 136:520-530.

- Kesler, Dylan C.; Haig, Susan M. (2007). "Multiscale Habitat Use and Selection in Cooperatively Breeding Micronesian Kingfishers". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 71 (3): 765–772. doi:10.2193/2006-011. JSTOR 4495250. S2CID 4104260.

- Kesler, Dylan C.; Haig, Susan M. (2007). "Territoriality, Prospecting, and Dispersal in Cooperatively Breeding Micronesian Kingfishers (Todiramphus Cinnamominus Reichenbachii)". The Auk. 124 (2): 381. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[381:TPADIC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0004-8038. S2CID 14032686.

- Kesler, D.C., and S. M. Haig. 2005. "Microclimate and nest site selection in Micronesian kingfishers." Pacific Science 59:499-508.

- Kesler, D.C. 2006. Population demography, resource use, and movement in cooperatively breeding Micronesian Kingfishers. Doctoral dissertation. Oregon State University. Corvallis, OR.

- Kesler, Dylan C.; Haig, Susan M. (2004). "Thermal characteristics of wild and captive Micronesian kingfisher nesting habitats". Zoo Biology. 23 (4): 301–308. doi:10.1002/zoo.20010.

- Fry, C.H., K. Fry, A. Harris. 1992. Kingfishers, Bee-eaters, and Rollers. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ.

- Haig, S.M., and J.D. Ballou. 1995. Genetic diversity among two avian species formerly endemic to Guam. Auk 112: 445–455.

- Haig, S.M., J.D. Ballou, and N.J. Casna. 1995. Genetic identification of kin in Micronesian Kingfishers. Journal of Heredity 86: 423–431.

- Marshall, S.D. 1989. Nest sites of the Micronesian Kingfisher on Guam. Wilson Bulletin 101, 472–477.

- Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1987. The Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ.

- Savidge, J. A. 1987. Extinction of an island forest avifauna by an introduced snake. Ecology 68:660-668.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2004. Draft Revised Recovery Plan for the Sihek or Guam Micronesian Kingfisher (Halcyon cinnamomina cinnamomina).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1984. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants: determination of endangered status for seven birds and two bats on Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. Federal Register 50 CFR Part 17 49(167), 33881–33885.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2004. Draft Revised Recovery Plan for the Sihek or Guam Micronesian Kingfisher (Halcyon cinnamomina cinnamomina). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR.

External links

- BirdLife Species Factsheet.

- Micronesian kingfisher Naturalis The Netherlands

- Philadelphia Zoo - Description of Guam Micronesian kingfisher Conservation efforts

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service - Threatened and Endangered Animals in the Pacific Islands.

- US Geological Survey - USGS Micronesian Avifauna Conservation Projects

- US Geological Survey - The Brown Treesnake on Guam.