Pep (dog): Difference between revisions

start article |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 00:35, 27 February 2024

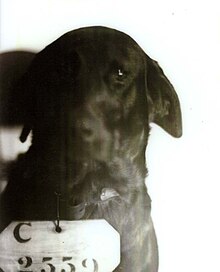

Mugshot of Pep | |

| Species | Canis familiaris |

|---|---|

| Breed | Labrador Retriever |

| Sex | Male |

| Born | c. 1923 |

| Died | 1930 Graterford, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | Prison dog, therapy dog |

| Training | Rat-catching |

| Residence | Grey Towers |

| Years active | 1924–1930 |

| Known for | Falsely accused of murdering a cat |

| Criminal charge | Murder |

| Penalty | Life sentence |

| Details | |

| State(s) | Pennsylvania |

| Imprisoned at | Eastern State Penitentiary |

Pep (c. 1923 – 1930) was a black Labrador Retriever who was falsely accused of murdering a cat. He belonged to Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot and was sent to live alongside the inmates of the Eastern State Penitentiary in 1924. While Pep had an inmate number, had his mugshot and pawprints taken, and was logged into the prison ledger as having received a life sentence, he was not a prisoner. He had been a gift from Pinchot to boost the morale of the inmates. Pep lived at the penitentiary for several years, later retiring to the Graterford Prison Farm.

He chased rats in the prison corridors and had to be put on a diet in his later years.

Early life

Pep was a Labrador Retriever[a] born around 1923 and given as a gift to Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot from the nephew of his wife, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot. Pep joined the Pinchot family at Grey Towers residence in Milford, Pennsylvania, during the governor's first term. According to Pinchot, "He belonged to my son, Giff,[b] and was distinguished by the fact that he was anybody's and everybody's dog."[1] Pep was described as "rather unusually intelligent"[3] though he chewed on the cushions of the sofa that sat on their front porch.[4]

Pinchot was inspired by the example set by governor of Maine Percival Baxter, would had recently sent his collie "Governor" to the Thomaston State Prison to serve as a therapy dog.[4] The Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia had become overcrowded and the inmates had low morale.[3] Cornelia Pinchot made a telephone call to Colonel John C. Broome, the warden of the penitentiary, to ask if the prisoners would like a dog as a pet.[5] Governor Pinchot wrote a letter to the warden of the Eastern State Penitentiary on July 29, 1924, offering up Pep to the institution.[3]

Imprisonment

Pep was taken to the penitentiary on August 31, 1924. He was received in "due and ancient form",[1] given the inmate number C-2559, had his mugshot and paw prints taken,[6] and was entered into the official prison ledger. His entry listed his crime as murder, his alias as "A Dog", and his sentence as life imprisonment.[7] The prison's supervisor of rehabilitation, E. Preston Sharp, provided a transcript of Pep's formal citation in the prison ledger, "C-2559. Pep. (A dog.) Received 8-31-'24. From Pike County, Pa. All black, Chesapeake retriever. Sent by Governor Gifford Pinchot. 'To Life term for killing the governor's pet cat."[1]

Allegations of cat-murder

Following Pep's move to the penitentiary, newspapers ran stories on the topic, seizing on the detail that the dog had been sent to prison for killing one of the governor's cats. Pep was characterized as a "cat-murdering dog" and journalists embellished the tale with claims that the cat had belonged to his wife or that there had been a trial where Pinchot served as the judge.

The governor received thousands of letters about the imprisonment of the dog. He would read some to his family, with one of the best concluding "any day, any dog is better than any politician anyway."[8]

Pinchot wrote "Some newspaperman drawing strictly and solely on his imagination, wrote a story to the effect that the dog had been condemned to prison because he killed a cat. That wretched tale went, literally, all over the world. I got letters from every quarter of the globe, denouncing my inhuman cruelty in 'condemning the poor beast to imprisonment merely because he had followed his instincts'. These letters came largely, to judge from the handwriting, from ladies of a certain age. They kept coming, all through the rest of my term. I never saw a better illustration of the impossibility of catching up with a lie-harmless as this lie was intended to be."[1]

Cornelia Pinchot later tried to clear up the misconception that Pep was sentenced to life in prison. She gave an interview to The New York Times in January 1926 and was quoted as saying "Why, Pep never killed anything or anybody. The report of his crime has circled half around the world, and the governor and I have received volumes of letters, telegrams, resolutions and petitions complaining of the cruelty of cooping the dog up in prison."[9][10]

Periodically, the mugshot of Pep with a prisoner number would reappear in print. Pinchot's son wrote to local newspapers in an attempt to correct the misinformation about Pep being a cat-murderer.[11]

Life in prison

Pep wandered the prison and the grounds freely and was well-liked by both prisoners and guards. He served as a mascot for the prison and was intended to boost the morale of the prisoners as a therapy dog. An article in the Philadelphia Inquirer opined "No despairing man brooding in his cell can feel that he is forgotten by God and man, who will feel Pep's loving tongue caressing his languid hand."[12][13]

In 1925, Pep was featured in a radio program that was broadcast from the penitentiary and aired on WIP. The Boston Daily Globe published an article on December 26, 1925, with a photograph of Pep in front of a radio microphone and surrounded by prison guards.[7]

Pep accompanied guards on their nightly rounds and excelled at rat-catching in the prison corridors. According to Sharp he "was quite fast for his size and weight (weight unknown, though heavy); being the equal of smaller and lighter dogs."[1] In addition to the rats and his regular meals, Pep was fed morsels by inmates and guards alike. He gained weight and by 1927 was put on a diet.[14] Pinchot visited the prison and Pep on several occasions. The governor related that he had seen Pep "in the penitentiary a number of times, and he was fat and healthy. But toward the end of his career he developed a partiality toward the officials of the institution and was with them more than with the prisoners."[1]

Pep stayed at Eastern State Penitentiary until as late as 1929.[c] During his later time at the prison, he joined work crews sent to construct the Graterford Prison Farm, about 30 mi (48 km) north of Philadelphia, established in 1929.[15] Pep's time at the penitentiary probably did not coincide with that of Al Capone, who was transferred there on August 8, 1929.[16]

Pep grew close to J.C. Burke, a captain of the Night Guard. In 1929, Pep was "pardoned" and transferred to the prison farm in Graterford. A 1935 newspaper article related that Pep had grown "too fat and unwieldy and ancient for active prison service. So he was 'pardoned' and allowed to spend the rest of his days at the home of a retired guard who begged leave to care for him in his old age."[1] Pep died in 1930 and was buried in a flower bed on prison grounds.[1][17]

The Eastern State Penitentiary, later converted to a museum, has a placard for Pep as one of the "notable inmates" and sells stuffed animals of the dog in its shop.[8]

Notes

- ^ Many newspaper articles from the 1920s and 1930s refer to Pep as a black Chesapeake Bay Retriever[1] or, less plausibly, an Irish Setter.[2]

- ^ Pinchot's son, Gifford Bryce Pinchot, was born in 1915.

- ^ According to the Eastern State Penitentiary website, Pep only stayed there two years before being sent to Graterford.[3]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Terhune, Albert Payson (October 28, 1934). "When Dogs Go to Prison". The Billings Gazette. pp. 5, 11, 13.

- ^ "The Penitentiary Dog". The New York Times. January 15, 1926.

- ^ a b c d Feeney, Connor. "Pets in Prison: From Pep to the Present". Eastern State Penitentiary. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Dog That Went to Jail For Life". Abilene Morning Reporter. September 7, 1924. p. 39.

- ^ "Mystery of 'Pep' Made Clear by Mrs. Pinchot". Altoona Mirror. January 14, 1926. p. 1.

- ^ Paietta, Ann C.; Kauppila, Jean (2023). Famous Animals in History and Popular Culture. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3553-8.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Emma (August 4, 2015). "Why 'Pep' The Prison Dog Got Such A Bum Rap". NPR.

- ^ a b "Grey Towers' prison pooch got a bum rap". Pocono Record. August 30, 2014.

- ^ "Mrs. Pinchot Clears Record of Her Dog". The New York Times. January 14, 1926. p. 2.

- ^ Teeuwisse, Jo (2023). Fake History: 101 Things that Never Happened. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7535-5970-3.

- ^ White, Bill (May 31, 1994). "Gov. Pinchot Didn't Arrest His Labrador". Morning Call. p. B01.

- ^ Beamish, R. J. (August 12, 1924). "Gov. Pinchot's dog sentenced to 'pen'". Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 3.

- ^ Jalongo, Mary Renck (2019). Prison Dog Programs: Renewal and Rehabilitation in Correctional Facilities. Springer Nature. p. viii. ISBN 978-3-030-25618-0.

- ^ "One Prisoner Is Apparently Happy". New Castle News. August 9, 1927. p. 14.

- ^ Dolan, Francis X. (2007). Eastern State Penitentiary. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-1863-9.

- ^ Hitchens, Josh (2022). Haunted History of Philadelphia. Arcadia Publishing. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-4671-5158-0.

- ^ Chinn, Hannah (October 31, 2019). "History behind the walls: How Philadelphia's most famous haunted house began". WHYY.

External links

- Pets in Prison: From Pep to the Present, Eastern State Penitentiary

- Pep at Find a Grave