Sand tiger shark: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Formatting (refs mostly) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''sand tiger shark''' (''Carcharias taurus''), '''grey nurse shark''', '''spotted ragged-tooth shark''', or '''blue-nurse sand tiger''' is a species of shark that inhabits subtropical and temperate waters worldwide. It lives |

The '''sand tiger shark''' (''Carcharias taurus''), '''grey nurse shark''', '''spotted ragged-tooth shark''', or '''blue-nurse sand tiger''' is a species of shark that inhabits subtropical and temperate waters worldwide. It lives across the whole continental shelf, from sandy shorelines (hence the name sand tiger shark) and submerged reefs right up to the edge of the continental shelf. It is not related at all to the tiger shark ''Galeocerdo cuvier'', but it is a cousin of the great white shark ''Carcharodon carcharias''. They dwell the waters of Japan, Australia, South Africa, the Mediterranean and the east coasts of North and South America. Despite its fearsome appearance and strong swimming ability, it is a relatively placid and slow-moving shark with no confirmed human fatalities. This species has a sharp, pointy head, and a bulky body. The sand tiger's length can reach {{convert|3.0|m|sp=us}}. They are grey with reddish-brown spots on their backs. Shivers (groups) have been observed to hunt large schools of fish. Their diet consists of bony fish, crustaceans, squid, and skates. Unlike other sharks, the sand tiger can gulp air from the surface, allowing it to be suspended in the water column with minimal effort. During pregnancy, the most developed embryo will feed upon its siblings, a reproductive strategy known as [[intrauterine cannibalism]]. The sand tiger is categorized as vulnerable on the [[IUCN Red List|International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List]]. It is the most widely kept shark in public aquariums owing to its large size and tolerance for captivity. |

||

==Taxonomy== |

==Taxonomy== |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

==Common names== |

==Common names== |

||

Because the sand tiger shark is worldwide in distribution it has many common names. The term "sand tiger shark" actually refers to four different sand tiger shark species in the family Odontaspididae. Furthermore the name creates confusion with the tiger shark |

Because the sand tiger shark is worldwide in distribution it has many common names. The term "sand tiger shark" actually refers to four different sand tiger shark species in the family Odontaspididae. Furthermore the name creates confusion with the tiger shark ''Galeocerdo cuvier'' which is not related to the sand tiger at all. The ''grey nurse shark'', the name used in Australia and the United Kingdom, is the second-most-used name for the shark, and in India it is known as ''blue-nurse sand tiger''. However, there are other and unrelated nurse sharks as well, in the family Ginglymostomatidae. The most unambiguous and descriptive English name is probably the South African one, ''spotted ragged-tooth shark'' .<ref name=fishbase>{{cite web |title=Common names of ''Carcharias taurus'' |url=http://www.fishbase.org/comnames/CommonNamesList.php?ID=747&GenusName=Carcharias&SpeciesName=taurus&StockCode=763 |accessdate=December 4, 2011 |year=2011 |work=FishBase}}</ref> |

||

==Identification== |

==Identification== |

||

There are four species of sand tiger sharks<ref name="Compagno1" /> |

There are four species of sand tiger sharks<ref name="Compagno1" /> |

||

# The sand tiger shark |

# The sand tiger shark ''Carcharias taurus'' |

||

# The Indian sand tiger shark |

# The Indian sand tiger shark ''Carcharias tricuspidatus''. Very little is known about this species which, described before 1900, is probably the same as (a synonym of) the sand tiger ''C. taurus''. |

||

# The small-toothed sand tiger shark |

# The small-toothed sand tiger shark ''Odontaspis ferox''. This species has a worldwide distribution, is seldom seen but normally inhabits deeper water than does ''C. taurus''. |

||

# The large-eyed sand tiger shark |

# The large-eyed sand tiger shark ''Odontaspis noronhai'' of which little is known and which is a deep water shark of the Americas. |

||

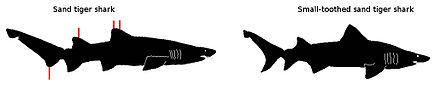

[[File:Sandtigersharkspecies.jpg|thumb|upright=2.0|Diagram indicating the differences between |

[[File:Sandtigersharkspecies.jpg|thumb|upright=2.0|Diagram indicating the differences between ''C. taurus'' and ''O. ferox'']] |

||

The most likely problem in identifying the sand tiger shark, is in the presence of either of the two species of |

The most likely problem in identifying the sand tiger shark, is in the presence of either of the two species of ''Odontaspis''. However, there are several differences |

||

# The bottom part of the caudal tail of the sand tiger is smaller; |

# The bottom part of the caudal tail of the sand tiger is smaller; |

||

# The front dorsal fin of the sand tiger is relatively non-symmetric; |

# The front dorsal fin of the sand tiger is relatively non-symmetric; |

||

| Line 50: | Line 49: | ||

In August 2007, an [[albino]] specimen was photographed off [[South West Rocks]], Australia.<ref name=albino>{{cite news |url=http://www.news.com.au/dailytelegraph/story/0,22049,22204963-5007132,00.html |title=Rare albino shark rules deep |author=Samantha Williams |accessdate=2008-08 |publisher=thetelegraph.com.au |date=8 August 2007}}</ref> |

In August 2007, an [[albino]] specimen was photographed off [[South West Rocks]], Australia.<ref name=albino>{{cite news |url=http://www.news.com.au/dailytelegraph/story/0,22049,22204963-5007132,00.html |title=Rare albino shark rules deep |author=Samantha Williams |accessdate=2008-08 |publisher=thetelegraph.com.au |date=8 August 2007}}</ref> |

||

==Habitat and range== |

==Habitat and range== |

||

=====Geographical range===== |

=====Geographical range===== |

||

Sand tiger sharks roam the [[epipelagic]] and [[mesopelagic]] regions of the ocean,<ref name=behavior1>{{cite web|url=http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Gallery/DeSCRIPT/Sandtiger/Sandtiger.html |title=Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department: Sand tiger Shark |accessdate=October 18, 2011 |year=2009 |publisher=Florida Museum of Natural History}}</ref> sandy coastal waters, estuaries, shallow bays, and rocky or tropical reefs, at depths of up to {{convert|19|m|ft|0|sp=us}}. However, sand tiger sharks inhabiting even deeper depths have been recorded. Sand tiger sharks have only been seen in Canadian waters three times: in the Minas Basin of Nova Scotia; near St. Andrews, New Brunswick; and off [[Point Lepreau]], New Brunswick.<ref>{{cite web | title = Sand Tiger Shark | publisher = WebWise | url = http://www.new-brunswick.net/new-brunswick/sharks/species/sandtiger.html | accessdate = December 24, 2011}}</ref> |

Sand tiger sharks roam the [[epipelagic]] and [[mesopelagic]] regions of the ocean,<ref name=behavior1>{{cite web|url=http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Gallery/DeSCRIPT/Sandtiger/Sandtiger.html |title=Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department: Sand tiger Shark |accessdate=October 18, 2011 |year=2009 |publisher=Florida Museum of Natural History}}</ref> sandy coastal waters, estuaries, shallow bays, and rocky or tropical reefs, at depths of up to {{convert|19|m|ft|0|sp=us}}. However, sand tiger sharks inhabiting even deeper depths have been recorded. Sand tiger sharks have only been seen in Canadian waters three times: in the Minas Basin of Nova Scotia; near St. Andrews, New Brunswick; and off [[Point Lepreau]], New Brunswick.<ref>{{cite web | title = Sand Tiger Shark | publisher = WebWise | url = http://www.new-brunswick.net/new-brunswick/sharks/species/sandtiger.html | accessdate = December 24, 2011}}</ref> |

||

| Line 60: | Line 59: | ||

[[File:RaggyMap2.jpg|thumb|upright=2.0|right|Annual movements of sand tiger sharks off South Africa and Australia]] |

[[File:RaggyMap2.jpg|thumb|upright=2.0|right|Annual movements of sand tiger sharks off South Africa and Australia]] |

||

=====Annual migration===== |

=====Annual migration===== |

||

Sand tigers in South Africa and Australia undertake an annual migration that may cover more than 1000 km.<ref |

Sand tigers in South Africa and Australia undertake an annual migration that may cover more than 1000 km.<ref name=j1/> They pup during the summer in relatively cold water (temperature around 16 degr C). After parturition, they swim northwards toward sites where there are suitable rocks or caves, often at a water depth around 20 m, where they mate during and just after the winter.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1071/MF10152}} |

||

</ref> Mating normally takes place at night. After mating they swim further north to even hotter water where gestation takes place. In the Autumn they return southwards to give birth in cooler water. This round trip may encompas as much as 3000 km. The young sharks do not take part in this migration, but they are absent from the normal birth grounds during winter: it is thought that they move deeper into the ocean.<ref> |

</ref> Mating normally takes place at night. After mating they swim further north to even hotter water where gestation takes place. In the Autumn they return southwards to give birth in cooler water. This round trip may encompas as much as 3000 km. The young sharks do not take part in this migration, but they are absent from the normal birth grounds during winter: it is thought that they move deeper into the ocean.<ref name=j1>{{cite doi|10.1071/MF06018}}</ref> At Cape Cod (USA) juveniles move away from coastal areas when water temperatures decreases below 16 degr C and day length decreases to less than 12 h.<ref>{{cite doi|10.3354/meps09989 }}</ref> Juveniles, however, return to their usual summer haunts and as they become immature they start larger migratory movements. |

||

==Behaviour== |

==Behaviour== |

||

[[File:The Sand Tiger Shark with Sea Turtle.jpg|thumb|The underbelly of a sand tiger shark, showing its pectoral fins]] |

[[File:The Sand Tiger Shark with Sea Turtle.jpg|thumb|The underbelly of a sand tiger shark, showing its pectoral fins]] |

||

=====Hunting===== |

=====Hunting===== |

||

The sand tiger shark is a nocturnal feeder. Evidence shows that, during the day, they take shelter near rocks, overhangs, caves and reefs often at relatively shallow depths (<20m). This is the typical environment where divers encounter sand tigers. However, at night they leave the shelter and hunt over the ocean bottom, often ranging far from their shelter<ref name="RSAFood1"/> |

The sand tiger shark is a nocturnal feeder. Evidence shows that, during the day, they take shelter near rocks, overhangs, caves and reefs often at relatively shallow depths (<20m). This is the typical environment where divers encounter sand tigers. However, at night they leave the shelter and hunt over the ocean bottom, often ranging far from their shelter.<ref name="RSAFood1"/> Sand tigers hunt by stealth. It is the only shark known to gulp air and store it in the shark's stomach, allowing the shark to maintain near-neutral buoyancy which helps it to hunt motionlessly and quietly.<ref name="Compagno1">Compagno, L. J. V. 1984. ‘FA0 Species Catalogue, Vol. 4. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 1, Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes’, FAO Fisheries Synopsis, No. 125, Vol. 4, Pt 1.</ref> When it comes close enough to a prey item, aquarium observations indicate that it grabs with a quick sideways snap of the prey. The sand tiger shark has been observed to gather in hunting groups when preying upon large schools of fish.<ref name="Compagno1" /> |

||

=====Diet===== |

=====Diet===== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Mustelus mustelus2.jpg|thumb|right|A bottom-living smooth-hound shark, one of the important prey items of sand tiger sharks]] |

||

The diet of the sand tiger comprises mostly bony fish (Teleosts), sharks and skates. The majority of prey items of sand tigers are demersal (i.e. from the sea bottom), suggesting that they hunt extensively on the sea bottom as far out as the continental shelf. Bony fish form about 60% of sand tigers food, the remaining prey comprising sharks and skates. In Argentina, the bony fish prey mostly included mostly demersal fishes, e.g. the striped weakfish ( |

The diet of the sand tiger comprises mostly bony fish (Teleosts), sharks and skates. The majority of prey items of sand tigers are demersal (i.e. from the sea bottom), suggesting that they hunt extensively on the sea bottom as far out as the continental shelf. Bony fish form about 60% of sand tigers food, the remaining prey comprising sharks and skates. In Argentina, the bony fish prey mostly included mostly demersal fishes, e.g. the striped weakfish (''Cynoscion guatucupa''). The most important elasmobranch prey was the bottom-living smoothhound shark (''Mustelus schmitii''). A number of benthic (i.e. free-swimming) rays and skates were also taken.<ref name= "ArgFood1">{{cite doi|10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00247.x}}</ref> Further, stomach contents analysis also indicated that smaller sand tigers mainly focus on the sea bottom, but as they grow larger they start to take more benthic prey. This perspective of the diet of sand tigers is consistent with similar observations in the north west Atlantic<ref>{{cite doi|10.1023/A:1007527111292}}</ref> and in South Africa where large sand tigers captured a wider range shark and skate species as prey, from the surf zone all the way to the continental shelf.<ref name= "RSAFood1">{{cite doi|10.2989/18142320509504091}}</ref> This indicates the opportunistic nature of sand shark feeding. Off South Africa, sand tigers less than 2 m in length preyed on fish about a quarter of their own length. However, large sand tigers captured prey up to about half of their own length.<ref name="RSAFood1"/> The prey items were usually swallowed as three or four chunks.<ref name="ArgFood1"/> |

||

=====Courtship and mating===== |

=====Courtship and mating===== |

||

Mating occurs around the months of March and April in the northern hemisphere and during |

Mating occurs around the months of March and April in the northern hemisphere and during August–October in the southern hemisphere. The courtship and mating of sand tigers has been best documented from observations in large aquaria. In Oceanworld, Sydney, the females tended to hover just above the sandy bottom ("shielding") when they were receptive.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1007/BF00842912}}</ref> This prevented males from approaching from underneath towards their cloaca. Often there is more than one male close by and the dominant one remains close to the female, but intimidates others with an aggressive display in which the dominant closely follows the lower ranking male. This forces the subordinate to accelerate and swim away. The dominant male snaps at smaller fish of other species. The male approaches the female and the two sharks protect the sandy bottom over which they interact. Strong interest of the male is indicates by superficial bites in the anal and pectoral fin areas of the female, upon which the female responds with superficial biting of the male. This behaviour continues for several days during which the male patrols the area around the female. The male regularly approaches the female in "nosing" behaviour to "smell" the cloaca of the female. If she is raedy, she swinms off with the male, while both partners contort their bodies so that the right clasper of the male enters the cloaca of the female while he bites the base of her right pectoral fin, leaving scars that are easily visible afterwards. After one or two minutes, mating is complete and the two separate. Females often mate with more than one male.<ref name="Chapman1">{{cite pmid|23637391}}</ref> Females mate only every second or third year.<ref name="SepRaggies">{{cite doi|10.3354/meps07741}}</ref> After mating, the females remain behind after the males have move off to seek other areas to feed,<ref name="SepRaggies" /> resulting in amy observations of sand tiger populations comprising almost exclusively females. |

||

==Reproduction and growth== |

==Reproduction and growth== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Growth curve for raggedtooth shark.jpg|thumb|left|Growth curve for sand tiger sharks in the north Atlantic]] |

||

=====Reproduction===== |

=====Reproduction===== |

||

The reproductive pattern is similar to that of many of the Lamnidae, the shark family to which sand tigers belong. Female sand tigers have two uterine horns that, during early embryonic development, may have as many as 50 embryos that obtain nutrients from their yolk sacs and possibly consume uterine fluids. When one of the ebryos reaches some {{convert|10|cm|in|0|sp=us}} in length, it eats all the smaller embryos so that only one large embryo remains in each uterine horn, a process called [[intrauterine cannibalism]] (oophagy)<ref name="Compagno1" /><ref name="Chapman1" /> |

The reproductive pattern is similar to that of many of the Lamnidae, the shark family to which sand tigers belong. Female sand tigers have two uterine horns that, during early embryonic development, may have as many as 50 embryos that obtain nutrients from their yolk sacs and possibly consume uterine fluids. When one of the ebryos reaches some {{convert|10|cm|in|0|sp=us}} in length, it eats all the smaller embryos so that only one large embryo remains in each uterine horn, a process called [[intrauterine cannibalism]] (oophagy).<ref name="Compagno1" /><ref name="Chapman1" /> These surviving embryos continue to feed on a steady supply of unfertilised eggs.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Gilmore, R.G.; Dodrill, J.W. and Linley, P. |year=1983|url=http://fishbull.noaa.gov/81-2/gilmore.pdf|title=Reproduction and embryonic development of the sand tiger shark, ''Odontaspis taurus'' (Rafinesque)|journal=Fishery Bulletin |volume=81|issue=2|pages=201–225}}</ref> After a lengthy labour, the female gives birth to {{convert|1|m|ft|0|sp=us}} long, fully independent offspring. The [[gestation]] period is approximately eight to twelve months. Taking into account that these sharks give birth only every second or third year,<ref name="SepRaggies" /> this results in an overall mean reproductive rate of less than one pup per year, one of the lowest reproductive rates for sharks. |

||

=====Growth===== |

=====Growth===== |

||

In the north Atlantic sand tiger sharks are born about 1 m in length. During the first year they grow about 27 |

In the north Atlantic sand tiger sharks are born about 1 m in length. During the first year they grow about 27 cm to reach 1.3 m. After that the growth rate decreases by about 2.5 cm each year until it stabilises at about 7 cm/y.<ref name="RAge1">{{cite journal| doi=10.1577/1548-8659(1994)123<0242:AAGEFT>2.3.CO;2| title=Age and Growth Estimates for the Sand Tiger in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean| year=1994| last1=Branstetter| first1=Steven| last2=Musick| first2=John A.| journal=Transactions of the American Fisheries Society| volume=123| issue=2| pages=242}}</ref> Males reach sexual maturity at an age of five to seven years and approximately {{convert|1.9|m|ft|0|sp=us}} in length. Females reach maturity when approximately {{convert|2.2|m|ft|0|sp=us}} long at about seven to ten years of age.<ref name="RAge1" /> They are normally not expected to reach lengths much over 3 m. In the informal media such as YouTube there have been several reports of sand tigers around five meters in length, but none of these have been verified scientifically. |

||

==Interaction with humans== |

==Interaction with humans== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The sand tiger is often associated with being vicious or deadly, due to their relatively large size and sharp, protruding teeth that point outward from their jaws, however they are quite docile, and aren't a threat to humans: their mouths are not large enough to cause a human fatality. Sand tigers roam the surf, sometimes in close proximity to humans, and there have been only a few instances of unprovoked sand tiger shark attacks on humans, these usually being associated with spear fishing, line fishing or shark feeding |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The sand tiger is often associated with being vicious or deadly, due to their relatively large size and sharp, protruding teeth that point outward from their jaws, however they are quite docile, and aren't a threat to humans: their mouths are not large enough to cause a human fatality. Sand tigers roam the surf, sometimes in close proximity to humans, and there have been only a few instances of unprovoked sand tiger shark attacks on humans, these usually being associated with spear fishing, line fishing or shark feeding.<ref name=NatGeo/> As at 2013 the official data base of Shark Attack Survivors [http://www.sharkattacksurvivors.com] does not list any fatalities due to sand tiger sharks. When the sharks become aggressive they tend to steal the fish or bait rather than attacking humans. Owing to its large size and docile temperament, the sand tiger is commonly displayed in aquariums around the world.<ref name=NatGeo>{{cite web |url=http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/sandtiger-shark.html |title=Sand Tiger Shark |accessdate=October 26, 2011 |year=2009 |publisher=National Geographic Society}}</ref> These sharks were also recently used in a successful experiment in [[artificial uterus]] development.<ref>Venton, Danielle (2011-09-29). [http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/09/artificial-shark-uterus/ Baby Sharks Birthed in Artificial Uterus]. wired.com</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In Australia and South Africa one of the common practices in beach holiday areas is to erect shark nets around the beaches frequently used by swimmers. These nets are erected some 400m from the shore and act as gill nets that trap incoming sharks<ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In Australia and South Africa one of the common practices in beach holiday areas is to erect shark nets around the beaches frequently used by swimmers. These nets are erected some 400m from the shore and act as gill nets that trap incoming sharks:<ref>{{cite doi|10.1016/S0964-5691(96)00061-0}}</ref> this was the norm until about 2005. In South Africa, the mortality of sand tiger sharks caused a significant decrease in the length of these animals and it was concluded that the shark nets pose a significant threat to this species that has a very low reproductive rate<ref>{{cite doi|10.1071/MF05156}}</ref> Before 2000, these nets snagged about 200 sand tiger sharks per year in South Africa, of which only about 40% survived and were released alive.<ref>{{cite doi|10.2989/1814232X.2012.709967}}</ref> The efficiency of theses shark nets for the prevention of unprovoked shark attacks on bathers has been questioned, and since 2000 there has been a reduced use of these nets and alternative approaches are being developed. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

=====Competition for food between man and sand tiger sharks===== |

=====Competition for food between man and sand tiger sharks===== |

||

In Argentina, the prey items of sand tigers largely coincided with important commercial fisheries targets |

In Argentina, the prey items of sand tigers largely coincided with important commercial fisheries targets.<ref name="ArgFood1" /> These commercially exploited fish had already been significantly reduced in numbers. In this way, humans affect sand tiger food availability and the sharks, in turn, compete with humans for food that has already been heavily exploited by the fisheries industry. The same applies to the bottom-living sea catfish (''Galeichthys feliceps''), a fisheries resource off the South African coast.<ref name="RSAFood1" /> |

||

=====Effects of scuba divers on sand tiger sharks===== |

=====Effects of scuba divers on sand tiger sharks===== |

||

Sand tiger sharks are often the targets of scuba divers who wish to observe or photograph these animals. A study near Sydney in Australia found that the behaviour of the sharks are affected by the proximity of scuba divers.<ref> |

Sand tiger sharks are often the targets of scuba divers who wish to observe or photograph these animals. A study near Sydney in Australia found that the behaviour of the sharks are affected by the proximity of scuba divers.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1080/10236244.2011.569991}}</ref> Diver activity affects the aggregation, swimming and respiratory behaviour of sharks, but only at short time scales. The group size of scuba divers was less important in affecting sand tiger behaviour than the distance within which they approached the sharks. Divers approaching to within 3 m of sharks affected their behaviour but after the divers retreated, the sharks resume normal behaviour. Another study found that scuba divers are normally compliant when it comes to observing the Australian regulations for shark diving.<ref>{{cite pmid|20872140}}</ref> |

||

==Threats and conservation status== |

==Threats and conservation status== |

||

[[File:IUCN_conservation__category_for_ragged_tooth_shark.jpg|left|]] |

|||

======Threats to sand tiger sharks====== |

======Threats to sand tiger sharks====== |

||

The world population of the sand tiger has been reduced over twenty percent in the past ten years, which means the shark is considered vulnerable by the [[World Conservation Union]]. There are several factors contributing to the decline in the population of the sand tigers. Sand tigers reproduce at an unusually low rate. They can be caught by fishing trawlers, although they are more commonly caught with a [[fishing line]]. Sand tigers' fins are a popular trade item in Japan.<ref name=IUCNREDLIST/> [[Shark liver oil]] is a popular product in beauty products such as lipstick.<ref name=PDFNOAA>{{cite web |url=http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/species/sandtigershark_detailed.pdf |title=Sand tiger shark |accessdate=November 28, 2011 |year=2011 |publisher=NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service}}</ref> Thus, [[overfishing]] is a major contributor to the population decline. In northern Australia, nets are put in place to protect swimmers from sharks. Many sand tigers are caught in the nets, and then either strangled or taken by fishermen.<ref name=IUCNREDLIST/> [[Estuaries]] along the United States of America's eastern Atlantic coast houses many of the young sand tiger sharks. These estuaries are susceptible to [[non-point source pollution]] that is harmful to the pups<ref name=PDFNOAA/> |

The world population of the sand tiger has been reduced over twenty percent in the past ten years, which means the shark is considered vulnerable by the [[World Conservation Union]]. There are several factors contributing to the decline in the population of the sand tigers. Sand tigers reproduce at an unusually low rate. They can be caught by fishing trawlers, although they are more commonly caught with a [[fishing line]]. Sand tigers' fins are a popular trade item in Japan.<ref name=IUCNREDLIST/> [[Shark liver oil]] is a popular product in beauty products such as lipstick.<ref name=PDFNOAA>{{cite web |url=http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/species/sandtigershark_detailed.pdf |title=Sand tiger shark |accessdate=November 28, 2011 |year=2011 |publisher=NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service}}</ref> Thus, [[overfishing]] is a major contributor to the population decline. In northern Australia, nets are put in place to protect swimmers from sharks. Many sand tigers are caught in the nets, and then either strangled or taken by fishermen.<ref name=IUCNREDLIST/> [[Estuaries]] along the United States of America's eastern Atlantic coast houses many of the young sand tiger sharks. These estuaries are susceptible to [[non-point source pollution]] that is harmful to the pups.<ref name=PDFNOAA/> |

||

======Conservation status of sand tiger sharks====== |

======Conservation status of sand tiger sharks====== |

||

This species is therefore listed as ''vulnerable'' on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List,<ref name=IUCNREDLIST>{{IUCN |assessors=Pollard, D.; & Smith, A. |id=3854 |title=''Carcharias taurus'' |downloaded=November 29, 2011 |year=2009 |version=2011.2}}</ref> and as ''endangered'' under Queensland's [[Nature Conservation Act 1992]]. It is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service ''Species of Concern'', which are those species that the U.S. Government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, [[National Marine Fisheries Service]] (NMFS), has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. [[Endangered Species Act]]. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, any shark caught must be released immediately with minimal harm, and is considered a prohibited species, making it illegal to harvest any part of the sand tiger shark on the United States' Atlantic coast<ref name=PDFNOAA/> |

This species is therefore listed as ''vulnerable'' on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List,<ref name=IUCNREDLIST>{{IUCN |assessors=Pollard, D.; & Smith, A. |id=3854 |title=''Carcharias taurus'' |downloaded=November 29, 2011 |year=2009 |version=2011.2}}</ref> and as ''endangered'' under Queensland's [[Nature Conservation Act 1992]]. It is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service ''Species of Concern'', which are those species that the U.S. Government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, [[National Marine Fisheries Service]] (NMFS), has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. [[Endangered Species Act]]. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, any shark caught must be released immediately with minimal harm, and is considered a prohibited species, making it illegal to harvest any part of the sand tiger shark on the United States' Atlantic coast.<ref name=PDFNOAA/> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 03:48, 9 August 2013

| Sand tiger shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | Lamniformes Mackerel sharks

|

| Family: | Odontaspididae Sand tiger sharks

|

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. taurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharias taurus Rafinesque, 1810

| |

| |

| Range of the sand tiger shark | |

The sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus), grey nurse shark, spotted ragged-tooth shark, or blue-nurse sand tiger is a species of shark that inhabits subtropical and temperate waters worldwide. It lives across the whole continental shelf, from sandy shorelines (hence the name sand tiger shark) and submerged reefs right up to the edge of the continental shelf. It is not related at all to the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier, but it is a cousin of the great white shark Carcharodon carcharias. They dwell the waters of Japan, Australia, South Africa, the Mediterranean and the east coasts of North and South America. Despite its fearsome appearance and strong swimming ability, it is a relatively placid and slow-moving shark with no confirmed human fatalities. This species has a sharp, pointy head, and a bulky body. The sand tiger's length can reach 3.0 meters (9.8 ft). They are grey with reddish-brown spots on their backs. Shivers (groups) have been observed to hunt large schools of fish. Their diet consists of bony fish, crustaceans, squid, and skates. Unlike other sharks, the sand tiger can gulp air from the surface, allowing it to be suspended in the water column with minimal effort. During pregnancy, the most developed embryo will feed upon its siblings, a reproductive strategy known as intrauterine cannibalism. The sand tiger is categorized as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. It is the most widely kept shark in public aquariums owing to its large size and tolerance for captivity.

Taxonomy

The sand tiger shark's classification, Carcharias taurus was originally determined by Constantine Rafinesque, from a specimen caught off the coast of Sicily. Its taxonomic classification has been long disputed by shark experts. Twenty-seven years after Rafinesque's original naming, Müller and Henle, German biologists, changed the genus name from C. taurus to Triglochis taurus. The following year, Swiss-American naturalist Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz reclassified the shark as Odontaspis cuspidata based upon examples of fossilized teeth. Agassiz's name was used until 1961 when three paleontologists and ichthyologists, W. Tucker, E. I. White, and N. B. Marshall, requested the shark be returned to the genus Carcharias. The experts' request was rejected and Odontaspis was approved by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). When experts concluded that taurus belongs after Odontaspis, the name was changed to Odontaspis taurus. In 1977, a South African shark expert, Leonard J. V. Compagno, challenged the Odontaspis taurus name and substituted Eugomphodus, a somewhat unknown classification, for Odontaspis. Many taxonomists questioned his change stating there was not a significant difference between Odontaspis and Carcharias. After changing the name to Eugomphodus taurus, Compagno successfully advocated in establishing the sharks current classification as Carcharias taurus. Carcharias taurus means "bull shark". The ICZN approved this name, and today the name is used among shark experts.[2]

Common names

Because the sand tiger shark is worldwide in distribution it has many common names. The term "sand tiger shark" actually refers to four different sand tiger shark species in the family Odontaspididae. Furthermore the name creates confusion with the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier which is not related to the sand tiger at all. The grey nurse shark, the name used in Australia and the United Kingdom, is the second-most-used name for the shark, and in India it is known as blue-nurse sand tiger. However, there are other and unrelated nurse sharks as well, in the family Ginglymostomatidae. The most unambiguous and descriptive English name is probably the South African one, spotted ragged-tooth shark .[3]

Identification

There are four species of sand tiger sharks[4]

- The sand tiger shark Carcharias taurus

- The Indian sand tiger shark Carcharias tricuspidatus. Very little is known about this species which, described before 1900, is probably the same as (a synonym of) the sand tiger C. taurus.

- The small-toothed sand tiger shark Odontaspis ferox. This species has a worldwide distribution, is seldom seen but normally inhabits deeper water than does C. taurus.

- The large-eyed sand tiger shark Odontaspis noronhai of which little is known and which is a deep water shark of the Americas.

The most likely problem in identifying the sand tiger shark, is in the presence of either of the two species of Odontaspis. However, there are several differences

- The bottom part of the caudal tail of the sand tiger is smaller;

- The front dorsal fin of the sand tiger is relatively non-symmetric;

- The front dorsal fin of the sand tiger is closer to the pelvic fin than to the pectoral fin (i.e. the front dorsal fin is positioned further backwards in the case of the sand tiger);

- The hind dorsal fin of the sand tiger is almost as large as the front dorsal fin.

Description

The eyes of the sand tiger shark are small, lacking eyelids, one of the shark's many distinct characteristics.[5] The head is rather pointy, as opposed to round, while the snout is flattened with a conical shape. Its body is stout and bulky and its mouth extends beyond the eyes. The sand tiger shark usually swims with its mouth open displaying three rows of protruding, smooth-edged, sharp-pointed teeth. Adult sharks tend to have reddish-brown spots scattered around their entire body.[5] Juvenile sand tiger sharks have yellow-brown spots on their bodies.[6] The sand tiger shark has a grey back and white underside. The males have grey claspers with white tips located on the underside of their body. The caudal fin is elongated and has a long upper lobe. They have two large, broad-based grey dorsal fins set back beyond the pectoral fins.[7] The pectoral fins are triangular, and the tail is almost one-third as long as the shark's head. The sand tiger's length at sexual maturity averages 1.9 to 1.95 m (6.2 to 6.4 ft) in males and 2.2 m (7.2 ft) in females, the latter being the larger-bodied sex.[8] Large mature specimens can attain a length of 3.0 to 3.4 meters (9.8 to 11.2 ft). A specimen of 50 kg (110 lb) in weight is considered "medium"-sized while a 95 to 110 kg (209 to 243 lb) specimen is considered "average"-sized.[9][10] Sand tiger sharks have been reported to attain a maximum mass of 159 kg (351 lb), however some sources claim the specimen can attain a weight of 300 kg (660 lb).[10][11]

In August 2007, an albino specimen was photographed off South West Rocks, Australia.[12]

Habitat and range

Geographical range

Sand tiger sharks roam the epipelagic and mesopelagic regions of the ocean,[13] sandy coastal waters, estuaries, shallow bays, and rocky or tropical reefs, at depths of up to 19 meters (62 ft). However, sand tiger sharks inhabiting even deeper depths have been recorded. Sand tiger sharks have only been seen in Canadian waters three times: in the Minas Basin of Nova Scotia; near St. Andrews, New Brunswick; and off Point Lepreau, New Brunswick.[14] The sand tiger shark can be found in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas.[13]

In the Western Atlantic Ocean, the sand tiger shark is found in coastal waters around from the Gulf of Maine to Florida, in the northern Gulf of Mexico around the Bahamas and Bermuda, and from southern Brazil to northern Argentina. The sand tiger shark is also found in the eastern Atlantic Ocean from the Mediterranean Sea to the Canary Islands, at the Cape Verde Islands, along the coasts of Senegal and Ghana, and from southern Nigeria to Cameroon. In the western Indian Ocean, the shark's habitat ranges from South Africa to southern Mozambique, but it does not live around Madagascar. The sand tiger shark has also been sighted in the Red Sea and may be found as far east as India. In the western Pacific, it has been sighted in the waters around the coasts of Japan and Australia, but not New Zealand.[1]

Annual migration

Sand tigers in South Africa and Australia undertake an annual migration that may cover more than 1000 km.[15] They pup during the summer in relatively cold water (temperature around 16 degr C). After parturition, they swim northwards toward sites where there are suitable rocks or caves, often at a water depth around 20 m, where they mate during and just after the winter.[16] Mating normally takes place at night. After mating they swim further north to even hotter water where gestation takes place. In the Autumn they return southwards to give birth in cooler water. This round trip may encompas as much as 3000 km. The young sharks do not take part in this migration, but they are absent from the normal birth grounds during winter: it is thought that they move deeper into the ocean.[15] At Cape Cod (USA) juveniles move away from coastal areas when water temperatures decreases below 16 degr C and day length decreases to less than 12 h.[17] Juveniles, however, return to their usual summer haunts and as they become immature they start larger migratory movements.

Behaviour

Hunting

The sand tiger shark is a nocturnal feeder. Evidence shows that, during the day, they take shelter near rocks, overhangs, caves and reefs often at relatively shallow depths (<20m). This is the typical environment where divers encounter sand tigers. However, at night they leave the shelter and hunt over the ocean bottom, often ranging far from their shelter.[18] Sand tigers hunt by stealth. It is the only shark known to gulp air and store it in the shark's stomach, allowing the shark to maintain near-neutral buoyancy which helps it to hunt motionlessly and quietly.[4] When it comes close enough to a prey item, aquarium observations indicate that it grabs with a quick sideways snap of the prey. The sand tiger shark has been observed to gather in hunting groups when preying upon large schools of fish.[4]

Diet

The diet of the sand tiger comprises mostly bony fish (Teleosts), sharks and skates. The majority of prey items of sand tigers are demersal (i.e. from the sea bottom), suggesting that they hunt extensively on the sea bottom as far out as the continental shelf. Bony fish form about 60% of sand tigers food, the remaining prey comprising sharks and skates. In Argentina, the bony fish prey mostly included mostly demersal fishes, e.g. the striped weakfish (Cynoscion guatucupa). The most important elasmobranch prey was the bottom-living smoothhound shark (Mustelus schmitii). A number of benthic (i.e. free-swimming) rays and skates were also taken.[19] Further, stomach contents analysis also indicated that smaller sand tigers mainly focus on the sea bottom, but as they grow larger they start to take more benthic prey. This perspective of the diet of sand tigers is consistent with similar observations in the north west Atlantic[20] and in South Africa where large sand tigers captured a wider range shark and skate species as prey, from the surf zone all the way to the continental shelf.[18] This indicates the opportunistic nature of sand shark feeding. Off South Africa, sand tigers less than 2 m in length preyed on fish about a quarter of their own length. However, large sand tigers captured prey up to about half of their own length.[18] The prey items were usually swallowed as three or four chunks.[19]

Courtship and mating

Mating occurs around the months of March and April in the northern hemisphere and during August–October in the southern hemisphere. The courtship and mating of sand tigers has been best documented from observations in large aquaria. In Oceanworld, Sydney, the females tended to hover just above the sandy bottom ("shielding") when they were receptive.[21] This prevented males from approaching from underneath towards their cloaca. Often there is more than one male close by and the dominant one remains close to the female, but intimidates others with an aggressive display in which the dominant closely follows the lower ranking male. This forces the subordinate to accelerate and swim away. The dominant male snaps at smaller fish of other species. The male approaches the female and the two sharks protect the sandy bottom over which they interact. Strong interest of the male is indicates by superficial bites in the anal and pectoral fin areas of the female, upon which the female responds with superficial biting of the male. This behaviour continues for several days during which the male patrols the area around the female. The male regularly approaches the female in "nosing" behaviour to "smell" the cloaca of the female. If she is raedy, she swinms off with the male, while both partners contort their bodies so that the right clasper of the male enters the cloaca of the female while he bites the base of her right pectoral fin, leaving scars that are easily visible afterwards. After one or two minutes, mating is complete and the two separate. Females often mate with more than one male.[22] Females mate only every second or third year.[23] After mating, the females remain behind after the males have move off to seek other areas to feed,[23] resulting in amy observations of sand tiger populations comprising almost exclusively females.

Reproduction and growth

Reproduction

The reproductive pattern is similar to that of many of the Lamnidae, the shark family to which sand tigers belong. Female sand tigers have two uterine horns that, during early embryonic development, may have as many as 50 embryos that obtain nutrients from their yolk sacs and possibly consume uterine fluids. When one of the ebryos reaches some 10 centimeters (4 in) in length, it eats all the smaller embryos so that only one large embryo remains in each uterine horn, a process called intrauterine cannibalism (oophagy).[4][22] These surviving embryos continue to feed on a steady supply of unfertilised eggs.[24] After a lengthy labour, the female gives birth to 1 meter (3 ft) long, fully independent offspring. The gestation period is approximately eight to twelve months. Taking into account that these sharks give birth only every second or third year,[23] this results in an overall mean reproductive rate of less than one pup per year, one of the lowest reproductive rates for sharks.

Growth

In the north Atlantic sand tiger sharks are born about 1 m in length. During the first year they grow about 27 cm to reach 1.3 m. After that the growth rate decreases by about 2.5 cm each year until it stabilises at about 7 cm/y.[25] Males reach sexual maturity at an age of five to seven years and approximately 1.9 meters (6 ft) in length. Females reach maturity when approximately 2.2 meters (7 ft) long at about seven to ten years of age.[25] They are normally not expected to reach lengths much over 3 m. In the informal media such as YouTube there have been several reports of sand tigers around five meters in length, but none of these have been verified scientifically.

Interaction with humans

Shark attacks on humans

The sand tiger is often associated with being vicious or deadly, due to their relatively large size and sharp, protruding teeth that point outward from their jaws, however they are quite docile, and aren't a threat to humans: their mouths are not large enough to cause a human fatality. Sand tigers roam the surf, sometimes in close proximity to humans, and there have been only a few instances of unprovoked sand tiger shark attacks on humans, these usually being associated with spear fishing, line fishing or shark feeding.[26] As at 2013 the official data base of Shark Attack Survivors [1] does not list any fatalities due to sand tiger sharks. When the sharks become aggressive they tend to steal the fish or bait rather than attacking humans. Owing to its large size and docile temperament, the sand tiger is commonly displayed in aquariums around the world.[26] These sharks were also recently used in a successful experiment in artificial uterus development.[27]

Nets around swimming beaches and their effects on sand tiger sharks

In Australia and South Africa one of the common practices in beach holiday areas is to erect shark nets around the beaches frequently used by swimmers. These nets are erected some 400m from the shore and act as gill nets that trap incoming sharks:[28] this was the norm until about 2005. In South Africa, the mortality of sand tiger sharks caused a significant decrease in the length of these animals and it was concluded that the shark nets pose a significant threat to this species that has a very low reproductive rate[29] Before 2000, these nets snagged about 200 sand tiger sharks per year in South Africa, of which only about 40% survived and were released alive.[30] The efficiency of theses shark nets for the prevention of unprovoked shark attacks on bathers has been questioned, and since 2000 there has been a reduced use of these nets and alternative approaches are being developed.

Competition for food between man and sand tiger sharks

In Argentina, the prey items of sand tigers largely coincided with important commercial fisheries targets.[19] These commercially exploited fish had already been significantly reduced in numbers. In this way, humans affect sand tiger food availability and the sharks, in turn, compete with humans for food that has already been heavily exploited by the fisheries industry. The same applies to the bottom-living sea catfish (Galeichthys feliceps), a fisheries resource off the South African coast.[18]

Effects of scuba divers on sand tiger sharks

Sand tiger sharks are often the targets of scuba divers who wish to observe or photograph these animals. A study near Sydney in Australia found that the behaviour of the sharks are affected by the proximity of scuba divers.[31] Diver activity affects the aggregation, swimming and respiratory behaviour of sharks, but only at short time scales. The group size of scuba divers was less important in affecting sand tiger behaviour than the distance within which they approached the sharks. Divers approaching to within 3 m of sharks affected their behaviour but after the divers retreated, the sharks resume normal behaviour. Another study found that scuba divers are normally compliant when it comes to observing the Australian regulations for shark diving.[32]

Threats and conservation status

Threats to sand tiger sharks

The world population of the sand tiger has been reduced over twenty percent in the past ten years, which means the shark is considered vulnerable by the World Conservation Union. There are several factors contributing to the decline in the population of the sand tigers. Sand tigers reproduce at an unusually low rate. They can be caught by fishing trawlers, although they are more commonly caught with a fishing line. Sand tigers' fins are a popular trade item in Japan.[1] Shark liver oil is a popular product in beauty products such as lipstick.[5] Thus, overfishing is a major contributor to the population decline. In northern Australia, nets are put in place to protect swimmers from sharks. Many sand tigers are caught in the nets, and then either strangled or taken by fishermen.[1] Estuaries along the United States of America's eastern Atlantic coast houses many of the young sand tiger sharks. These estuaries are susceptible to non-point source pollution that is harmful to the pups.[5]

Conservation status of sand tiger sharks

This species is therefore listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List,[1] and as endangered under Queensland's Nature Conservation Act 1992. It is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service Species of Concern, which are those species that the U.S. Government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, any shark caught must be released immediately with minimal harm, and is considered a prohibited species, making it illegal to harvest any part of the sand tiger shark on the United States' Atlantic coast.[5]

References

- ^ a b c d e Template:IUCN

- ^ "The Tangled Taxonomy of the Sandtiger Shark". ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Common names of Carcharias taurus". FishBase. 2011. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d Compagno, L. J. V. 1984. ‘FA0 Species Catalogue, Vol. 4. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 1, Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes’, FAO Fisheries Synopsis, No. 125, Vol. 4, Pt 1.

- ^ a b c d e "Sand tiger shark" (PDF). NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service. 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Sand shark Carcharias taurus Rafinesque 1810". United States Department of the Interior. 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "SAND TIGER SHARK". Florida Museum of Natural History. 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ FLMNH Ichthyology Department: Sandtiger Shark. Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- ^ The Sand Tiger Shark in GURPS. Panoptesv.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- ^ a b ADW: Carcharias taurus: INFORMATION. Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- ^ "Meet the Animals". The Maritime Aquarium of Long Island. 2011. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Samantha Williams (8 August 2007). "Rare albino shark rules deep". thetelegraph.com.au. Retrieved 2008-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department: Sand tiger Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History. 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Sand Tiger Shark". WebWise. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1071/MF06018, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1071/MF06018instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1071/MF10152, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1071/MF10152instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3354/meps09989 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3354/meps09989instead. - ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2989/18142320509504091, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2989/18142320509504091instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00247.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00247.xinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1023/A:1007527111292, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1023/A:1007527111292instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/BF00842912, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/BF00842912instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23637391, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23637391instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3354/meps07741, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3354/meps07741instead. - ^ Gilmore, R.G.; Dodrill, J.W. and Linley, P. (1983). "Reproduction and embryonic development of the sand tiger shark, Odontaspis taurus (Rafinesque)" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 81 (2): 201–225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Branstetter, Steven; Musick, John A. (1994). "Age and Growth Estimates for the Sand Tiger in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 123 (2): 242. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1994)123<0242:AAGEFT>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ a b "Sand Tiger Shark". National Geographic Society. 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Venton, Danielle (2011-09-29). Baby Sharks Birthed in Artificial Uterus. wired.com

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0964-5691(96)00061-0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0964-5691(96)00061-0instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1071/MF05156, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1071/MF05156instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2989/1814232X.2012.709967, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2989/1814232X.2012.709967instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/10236244.2011.569991, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/10236244.2011.569991instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20872140, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20872140instead.

Bibliography

External links

- The tangled taxonomic history of the sand tiger shark – Additional taxonomy information

- Carcharias taurus, Sand tiger shark from FishBase

- Species Description of Carcharias taurus at www.shark-references.com