Torosaurus: Difference between revisions

Moldovan0731 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

→Classification and debate: added cladogram after Sampson et al. (2010) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

==Classification and debate== |

==Classification and debate== |

||

{|style="margin-left: 1em;; margin-bottom: 0.5em; width: 248px; border: #99B3FF solid 1px; background-color: #FFFFFF; color: #000000; float: right; " |

|||

|{{clade| style=font-size:90%;line-height:90%; |

|||

|label1=[[Ceratopsidae]] |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=[[Centrosaurinae]] |

|||

|label2=[[Chasmosaurinae]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Chasmosaurus]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Mojoceratops]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Agujaceratops]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Utahceratops]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Pentaceratops]]'' }} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Coahuilaceratops]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Kosmoceratops]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Vagaceratops]]'' }} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Anchiceratops]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Arrhinoceratops]]'' |

|||

|label2=[[Triceratopsini]] |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Ojoceratops]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Eotriceratops]]'' |

|||

|3={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Torosaurus]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Nedoceratops]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Triceratops]]'' }} }} }} }} }} }} }} }} }} }} }} }} }} |

|||

<center><small>Theropod [[cladogram]] based on the [[phylogenetics|phylogenetic analysis]], conducted by Sampson ''et al.', in 2010.<ref name=pone0012292>{{cite journal|authors=Scott D. Sampson, Mark A. Loewen, Andrew A. Farke, Eric M. Roberts, Catherine A. Forster, Joshua A. Smith, and Alan A. Titus|title=New Horned Dinosaurs from Utah Provide Evidence for Intracontinental Dinosaur Endimism|journal=PLoS ONE|year=2010|series=5|issue=9|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0012292|url=http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0012292}}</ref></small></center> |

|||

|} |

|||

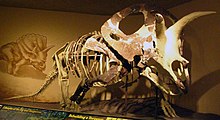

[[File:TorosaurusLatus.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Reconstructed skull of ''T. latus'']] |

[[File:TorosaurusLatus.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Reconstructed skull of ''T. latus'']] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

''Torosaurus'' has traditionally been classified as a genus closely related to ''[[Triceratops]]''<ref>Farke, A. A. "Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid ''Torosaurus latus''", pp. 235-257. In K. Carpenter (ed.). ''Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs''. Indiana Univ. Press (Bloomington), 2006.</ref> within the subfamily [[Ceratopsinae]] (later, [[Chasmosaurinae]]) of the [[Ceratopsidae]] family of the [[Ceratopsia]] (Greek: "horned face"), a group of herbivorous dinosaurs with [[parrot]]-like beaks which thrived in [[North America]] and [[Asia]] during the [[Jurassic]] and [[Cretaceous]] Periods. |

''Torosaurus'' has traditionally been classified as a genus closely related to ''[[Triceratops]]''<ref>Farke, A. A. "Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid ''Torosaurus latus''", pp. 235-257. In K. Carpenter (ed.). ''Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs''. Indiana Univ. Press (Bloomington), 2006.</ref> within the subfamily [[Ceratopsinae]] (later, [[Chasmosaurinae]]) of the [[Ceratopsidae]] family of the [[Ceratopsia]] (Greek: "horned face"), a group of herbivorous dinosaurs with [[parrot]]-like beaks which thrived in [[North America]] and [[Asia]] during the [[Jurassic]] and [[Cretaceous]] Periods. |

||

Paleontologists investigating dinosaur [[ontogeny]] in the [[Hell Creek Formation]] of [[Montana]] have hypothesized that ''Triceratops'' and ''Torosaurus'' may be growth stages in a single genus.<ref name=scannella&horner2010>Scannella, J. and Horner, J.R. (2010). "Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny ." ''Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology'', '''30'''(4): 1157 - 1168. {{doi|10.1080/02724634.2010.483632}}</ref> A 2009 paper by John Scannella reclassified the mature ''Torosaurus'' specimens as fully mature individuals of ''Triceratops''. [[Jack Horner (paleontologist)|Jack Horner]], Scannella's mentor at [[Montana State University System|Montana State University]], noted that ceratopsian skulls consist of [[metaplastic bone]]. A characteristic of metaplastic bone is that it lengthens and shortens over time, extending and resorbing to form new shapes. Significant variety is seen even in those skulls already identified as ''Triceratops'', Horner observed, "where the horn orientation is backwards in juveniles and forward in adults". Approximately 50% of all subadult ''Triceratops'' skulls have two thin areas in the frill that correspond with the placement of "holes" in ''Torosaurus'' skulls, suggesting that holes developed to offset the weight that would otherwise have been added as maturing ''Triceratops'' individuals grew longer frills.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091031002314.htm |title=New Analyses Of Dinosaur Growth May Wipe Out One-third Of Species |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2009-10-31 |accessdate=2010-08-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0007626}}</ref> In 2010 Scannella and Horner published their findings after examining the growth patterns in 38 skull specimens (29 of ''Triceratops'', 9 of ''Torosaurus'') from the Hell Creek formation. They concluded that ''Torosaurus'' actually represents the mature form of ''Triceratops''.<ref name=scannella&horner2010/> |

Paleontologists investigating dinosaur [[ontogeny]] in the [[Hell Creek Formation]] of [[Montana]] have hypothesized that ''Triceratops'' and ''Torosaurus'' may be growth stages in a single genus.<ref name=scannella&horner2010>Scannella, J. and Horner, J.R. (2010). "Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny ." ''Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology'', '''30'''(4): 1157 - 1168. {{doi|10.1080/02724634.2010.483632}}</ref> A 2009 paper by John Scannella reclassified the mature ''Torosaurus'' specimens as fully mature individuals of ''Triceratops''. [[Jack Horner (paleontologist)|Jack Horner]], Scannella's mentor at [[Montana State University System|Montana State University]], noted that ceratopsian skulls consist of [[metaplastic bone]]. A characteristic of metaplastic bone is that it lengthens and shortens over time, extending and resorbing to form new shapes. Significant variety is seen even in those skulls already identified as ''Triceratops'', Horner observed, "where the horn orientation is backwards in juveniles and forward in adults". Approximately 50% of all subadult ''Triceratops'' skulls have two thin areas in the frill that correspond with the placement of "holes" in ''Torosaurus'' skulls, suggesting that holes developed to offset the weight that would otherwise have been added as maturing ''Triceratops'' individuals grew longer frills.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091031002314.htm |title=New Analyses Of Dinosaur Growth May Wipe Out One-third Of Species |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2009-10-31 |accessdate=2010-08-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0007626}}</ref> In 2010 Scannella and Horner published their findings after examining the growth patterns in 38 skull specimens (29 of ''Triceratops'', 9 of ''Torosaurus'') from the Hell Creek formation. They concluded that ''Torosaurus'' actually represents the mature form of ''Triceratops''.<ref name=scannella&horner2010/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Other researchers have claimed distinct juvenile torosaurs have been excavated from a bonebed in the [[Javelina Formation]] of [[Big Bend National Park]], basing their identification as ''Torosaurus'' cf. ''utahensis'' on their proximity to an adult with a characteristic torosaurid parietal.<ref>Hunt, Rebecca K. and Thomas M. Lehman. 2008. Attributes of the ceratopsian dinosaur ''Torosaurus'', and new material from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of Texas. Journal of Paleontology 82(6): 1127-1138.</ref> |

Other researchers have claimed distinct juvenile torosaurs have been excavated from a bonebed in the [[Javelina Formation]] of [[Big Bend National Park]], basing their identification as ''Torosaurus'' cf. ''utahensis'' on their proximity to an adult with a characteristic torosaurid parietal.<ref>Hunt, Rebecca K. and Thomas M. Lehman. 2008. Attributes of the ceratopsian dinosaur ''Torosaurus'', and new material from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of Texas. Journal of Paleontology 82(6): 1127-1138.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:54, 16 November 2013

| Torosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,[1]

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton, Milwaukee | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Chasmosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Triceratopsini |

| Genus: | †Torosaurus Marsh, 1891 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Torosaurus ("perforated lizard", in reference to the large openings in its frill) is a genus of ceratopsid dinosaur that lived during the late Maastrichtian stage of the Cretaceous period, between 66.8 and 65.5 million years ago.[1] Fossils have been discovered across the Western Interior of North America, from Saskatchewan to south Texas. Torosaurus possessed one of the largest skulls of any known land animal. The frilled skull reached 2.6 metres (8.5 ft) in length. From head to tail, Torosaurus is thought to have measured about 8 to 9 m (26 to 30 ft) long[2][1] and weighed 4 to 6 tonnes (4.4 to 6.6 tons). Torosaurus is distinguished from the contemporary Triceratops by an elongate frill with large openings (fenestrae), long squamosal bones of the frill with a trough on their upper surface, and the presence of five or more pairs of hornlets (epoccipitals) on the back of the frill.[3] Torosaurus also lacked the long nose horn seen in Triceratops prorsus, and instead resembled the earlier and more primitive Triceratops horridus in having a short nose horn.[3] Two species have been named, Torosaurus latus and T. gladius. T. gladius is no longer considered a valid species, however.

Recently the validity of Torosaurus has been disputed.[4] A 2010 study of fossil bone histology concluded that Torosaurus probably represented a mature form of Triceratops, with the bones of Triceratops specimens still immature and showing signs of the development of the Torosaurus’ distinct frill holes.[5][6][7] 2011 and 2012 studies of external features of known specimens, however, claim that external morphological differences between the two genera preclude their synonymy.[8][3]

Discovery and species

In 1891, two years after the naming of Triceratops, a pair of ceratopsian skulls with elongated frills bearing holes were found in southeastern Wyoming by John Bell Hatcher. Paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh coined the genus Torosaurus for them. Similar specimens have since been found in Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, Utah and Saskatchewan. Fragmentary remains that could possibly be identified with the genus have been found in the Big Bend Region of Texas and in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico. Paleontologists have observed that Torosaurus specimens are relatively uncommon in the fossil record; specimens of Triceratops are more abundant.

The name Torosaurus is frequently translated as "bull lizard" from the Latin noun taurus but much more likely derives from the Greek verb τορέω (toreo, "pierce, perforate").[9] The allusion is to the fenestrae or ("window-like") holes in the elongated frill, which have traditionally served to distinguish it from the solid frill of Triceratops. Much of the confusion over etymology of the name results from the fact that Marsh never explicitly explained it in his papers.

Two Torosaurus species have been identified:

- T. latus Marsh, 1891 (type species)

- T. utahensis Gilmore, 1946

Another identification was subsequently regarded as a misassignment:

- T. gladius Marsh, 1891 (=T. latus)

Torosaurus utahensis was originally described as Arrhinoceratops utahensis by Gilmore in 1946. Review by Sullivan et al. in 2005[10] left it as Torosaurus utahensis and somewhat older than T. latus. However, subsequent studies suggested it may well be either Arrhinoceratops or a new genus, as dinosaurs from the northern Hell Creek formation and southern "Alamosaurus fauna" rarely overlap and were probably separated by a geographic barrier. Research has not yet been published on whether T. utahensis should be regarded as a new genus or, as has been suggested for T. latus, the mature growth stage of some species of Triceratops.[5]

Classification and debate

|

|

Torosaurus has traditionally been classified as a genus closely related to Triceratops[12] within the subfamily Ceratopsinae (later, Chasmosaurinae) of the Ceratopsidae family of the Ceratopsia (Greek: "horned face"), a group of herbivorous dinosaurs with parrot-like beaks which thrived in North America and Asia during the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods.

Paleontologists investigating dinosaur ontogeny in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana have hypothesized that Triceratops and Torosaurus may be growth stages in a single genus.[5] A 2009 paper by John Scannella reclassified the mature Torosaurus specimens as fully mature individuals of Triceratops. Jack Horner, Scannella's mentor at Montana State University, noted that ceratopsian skulls consist of metaplastic bone. A characteristic of metaplastic bone is that it lengthens and shortens over time, extending and resorbing to form new shapes. Significant variety is seen even in those skulls already identified as Triceratops, Horner observed, "where the horn orientation is backwards in juveniles and forward in adults". Approximately 50% of all subadult Triceratops skulls have two thin areas in the frill that correspond with the placement of "holes" in Torosaurus skulls, suggesting that holes developed to offset the weight that would otherwise have been added as maturing Triceratops individuals grew longer frills.[13][14] In 2010 Scannella and Horner published their findings after examining the growth patterns in 38 skull specimens (29 of Triceratops, 9 of Torosaurus) from the Hell Creek formation. They concluded that Torosaurus actually represents the mature form of Triceratops.[5]

Other researchers have claimed distinct juvenile torosaurs have been excavated from a bonebed in the Javelina Formation of Big Bend National Park, basing their identification as Torosaurus cf. utahensis on their proximity to an adult with a characteristic torosaurid parietal.[15]

Scannella and Horner's findings have been directly challenged by a 2011 paper by Andrew Farke and a 2012 one by Nicholas Longrich. Farke redescribed the problematic Nedoceratops hatcheri as an aged individual of its own genus, against Scannella and Horner who argued for its identification with Triceratops. Farke further noted that the proposed development of a Triceratops into a Torosaurus would require additional epoccipitals, unusual bone development, and the establishment of holes in the frill at a late stage without precedent among ceratopsids.[8] Longrich argued against identification of Triceratops and Torosaurus on the basis of external development, finding several examples of juvenile torosaurs under his criteria and claiming that the ventral depressions found in Triceratops differ in shape and position from the fenestrae found among torosaurs.[3]

Paleobiology

All ceratopsians, including Torosaurus and Triceratops, were herbivores. The jaws contained rows of teeth that slid past each other as the jaws closed, creating a shearing action that would have allowed Torosaurus to process tough vegetation, perhaps the ferns that formed much of the ground cover. A slightly longer, narrower snout in Torosaurus than in Triceratops suggests that they might have had different feeding preferences.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix. Cite error: The named reference "Holtz2008" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press.

- ^ a b c d Longrich, N. R and Field, D. J. (2012). "Torosaurus is not Triceratops: Ontogeny in chasmosaurine ceratopsids as a case study in dinosaur taxonomy". PLoS ONE. 7 (2): e32623. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...7E2623L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032623.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Morph-osaurs: How shape-shifting dinosaurs deceived us - life - 28 July 2010". New Scientist. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483632. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ a b c d Scannella, J. and Horner, J.R. (2010). "Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny ." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30(4): 1157 - 1168. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483632

- ^ Switek, Brian. "New Study Says Torosaurus=Triceratops". Dinosaur Tracking. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Horner, Jack. TEDX Talks: "Shape-shifting Dinosaurs". Nov 2011. Accessed 20 Nov 2012.

- ^ a b Farke, A. A. (2011) "Anatomy and taxonomic status of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Nedoceratops hatcheri from the Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming, U.S.A.." PLoS ONE 6 (1): e16196. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016196

- ^ Dodson, P. The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton Univ. Press (Princeton), 1996.

- ^ Sullivan, R. M., A. C. Boere, and S. G. Lucas. 2005. Redescription of the ceratopsid dinosaur Torosaurus utahensis (Gilmore, 1946) and a revision of the genus. Journal of Paleontology 79:564-582.

- ^ "New Horned Dinosaurs from Utah Provide Evidence for Intracontinental Dinosaur Endimism". PLoS ONE. 5 (9). 2010. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012292.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Farke, A. A. "Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Torosaurus latus", pp. 235-257. In K. Carpenter (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Indiana Univ. Press (Bloomington), 2006.

- ^ "New Analyses Of Dinosaur Growth May Wipe Out One-third Of Species". Sciencedaily.com. 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007626, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0007626instead. - ^ Hunt, Rebecca K. and Thomas M. Lehman. 2008. Attributes of the ceratopsian dinosaur Torosaurus, and new material from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of Texas. Journal of Paleontology 82(6): 1127-1138.

- Dodson, P. (1996). The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, pp. xiv-346

- Haines, Tim & Chambers, Paul. (2006)The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Canada: Firefly Books Ltd.

External links

- http://www.dinosaurvalley.com/Visiting_Drumheller/Kids_Zone/Groups_of_Dinosaurs/index.php

- http://www.dinosaurier-web.de/galery/pages_t/torosaurus.html

- http://www.newscientist.com/articleimages/mg20727713.500/1-morphosaurs-how-shapeshifting-dinosaurs-deceived-us.html Chart showing Triceratops/Torosaur growth and development (New Scientist)