Tachypleus gigas: Difference between revisions

→Description: missing word |

moved common names to usual position; merged 3-sentence section into other, as related (if expanded, it can be divided again); rm. WP:REPEATLINK |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Tachypleus gigas''''', one of the four [[Extant taxon|extant]] (living) species of [[horseshoe crab]] |

'''''Tachypleus gigas''''', commonly known as the '''Indo-Pacific horseshoe crab''',<ref name="Food web">{{cite book |editor1=Carl N. Shuster Jr. |editor2=Robert B. Barlow |editor3=H. Jane Brockmann |year=2003 |title=The American Horseshoe Crab |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=978-0-674-01159-5 |author=Mark L. Bolton |author2=Carl N. Schuster Jr. with John A. Keinath |last-author-amp=yes |chapter=Horseshoe crabs in a food web: who eats whom? |pages=133–153 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0OSAKny-6M4C&pg=PA138}}</ref> '''Indonesian horseshoe crab''',<ref>{{cite book |editor1=Carl N. Shuster Jr. |editor2=Robert B. Barlow |editor3=H. Jane Brockmann |year=2003 |title=The American Horseshoe Crab |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=978-0-674-01159-5 |author1=Louis Leibovitz |author2=Gregory A. Lewbart |lastauthoramp=yes |chapter=Diseases and symbionts: vulnerability despite tough shells |pages=245–275 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0OSAKny-6M4C&pg=PA265}}</ref> '''Indian horseshoe crab''',<ref>{{cite book |editor=John T. Tanacredi |year=2001 |title=''Limulus'' in the Limelight: a Species 350 Million Years in the Making and in Peril? |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |isbn=978-0-306-46681-6 |author=Mark L. Botton |chapter=The conservation of horseshoe crabs: what can we learn from the Japanese experience? |pages=41–52 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CJiybSNmo7YC&pg=PA42}}</ref> or '''southern horseshoe crab''',<ref>{{cite web | url=http://horseshoecrabs.myspecies.info/content/identification-guide |title=Identification guide | publisher=Horseshoe Crab monitoring site |accessdate=26 June 2018 }}</ref> is one of the four [[Extant taxon|extant]] (living) species of [[horseshoe crab]]. It is found in coastal water in [[South Asia|South]] and [[Southeast Asia]] at depths to {{convert|40|m|ft|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Lazarus"/> It grows up to about {{convert|50|cm|in|abbr=on}} long, including the tail, and is covered by a sturdy [[carapace]] that is up to about {{convert|26.5|cm|in|abbr=on}} wide.<ref name=Jawahir2017>{{cite journal| author1=A. Raman Noor Jawahir | author2=Mohamad Samsur | author3=Mohd L. Shabdin | author4=Khairul-Adha A. Rahim | year=2017 | title=Morphometric allometry of horseshoe crab, Tachypleus gigas at west part of Sarawak waters, Borneo, East Malaysia | journal=AACL Bioflux | volume=10 | issue=1 | pages=18-24 }}</ref> |

||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

''T. gigas'' has a "sage green" [[chitin]]ous [[exoskeleton]].<ref name="Patil">{{cite journal |author1=J. S. Patil |author2=A. C. Anil |lastauthoramp=yes |year=2000 |title=Epibiotic community of the horseshoe crab ''Tachypleus gigas'' |journal=[[Marine Biology (journal)|Marine Biology]] |volume=136 |issue=4 |pages=699–713 |doi=10.1007/s002270050730 |url=http://drs.nio.org/drs/handle/2264/1623}}</ref> Despite the scientific name ''T. gigas'', the close relative ''[[Tachypleus tridentatus]]'' reaches a larger size. Both are considerably larger than ''[[Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda]]''.<ref name=AboutTheSpecies>{{cite web | url=http://www.horseshoecrab.org/nh/species.html |title=About the Species | publisher=The Horseshoe Crab |accessdate=26 June 2018 }}</ref> Like the other species, females of ''T. gigas'' grow larger than males. On average, females are about {{convert|42|cm|in|abbr=on}} long, including a tail ([[telson]]) that is about {{convert|20|cm|in|abbr=on}}, and their carapace ([[prosoma]]) is about {{convert|22|cm|in|abbr=on}} wide. In comparison, the average for males is about {{convert|34|cm|in|abbr=on}} long, including a tail that is about {{convert|17.5|cm|in|abbr=on}}, and their carapace is about {{convert|17.5|cm|in|abbr=on}} wide.<ref name=Jawahir2017/> The largest females reach a total length of more than {{convert|50|cm|in|abbr=on}} and can weigh more than {{convert|1.8|kg|lb|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Jawahir2017/> In addition to their smaller size, males have a paler and rougher |

''T. gigas'' has a "sage green" [[chitin]]ous [[exoskeleton]].<ref name="Patil">{{cite journal |author1=J. S. Patil |author2=A. C. Anil |lastauthoramp=yes |year=2000 |title=Epibiotic community of the horseshoe crab ''Tachypleus gigas'' |journal=[[Marine Biology (journal)|Marine Biology]] |volume=136 |issue=4 |pages=699–713 |doi=10.1007/s002270050730 |url=http://drs.nio.org/drs/handle/2264/1623}}</ref> Despite the scientific name ''T. gigas'', the close relative ''[[Tachypleus tridentatus]]'' reaches a larger size. Both are considerably larger than ''[[Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda]]''.<ref name=AboutTheSpecies>{{cite web | url=http://www.horseshoecrab.org/nh/species.html |title=About the Species | publisher=The Horseshoe Crab |accessdate=26 June 2018 }}</ref> Like the other species, females of ''T. gigas'' grow larger than males. On average, females are about {{convert|42|cm|in|abbr=on}} long, including a tail ([[telson]]) that is about {{convert|20|cm|in|abbr=on}}, and their [[carapace]] ([[prosoma]]) is about {{convert|22|cm|in|abbr=on}} wide. In comparison, the average for males is about {{convert|34|cm|in|abbr=on}} long, including a tail that is about {{convert|17.5|cm|in|abbr=on}}, and their carapace is about {{convert|17.5|cm|in|abbr=on}} wide.<ref name=Jawahir2017/> The largest females reach a total length of more than {{convert|50|cm|in|abbr=on}} and can weigh more than {{convert|1.8|kg|lb|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Jawahir2017/> In addition to their smaller size, males have a paler and rougher carapace, and act as hosts to a greater number of epibionts.<ref name="Patil"/> The tail bears a crest dorsally and is concave ventrally.<ref name="Lazarus"/> The anterior part of the tail is sharply serrated.<ref name="Gopalakrishnakone">{{cite book |author=P. Gopalakrishnakone |year=1990 |title=A Colour Guide to Dangerous Animals |publisher=[[National University of Singapore|NUS Press]] |isbn=978-9971-69-150-9 |chapter=Class Merostomata |pages=114–115 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HE5j0_P4DXcC&pg=PA114}}</ref> |

||

The carapace which shields the prosoma also bears two pairs of eyes – a pair of [[Simple eye in invertebrates|simple eyes]] at the front, and a pair of compound eyes positioned laterally. In common with other horseshoe crabs, ''T. gigas'' also has ventral eyes near the mouthparts, and [[photoreceptor protein|photoreceptors]] in the caudal spine.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/H/horseshoe_crab.html |title=Horseshoe crab |author=Liza Carruthers |work=The Internet Encyclopedia of Science |accessdate=January 22, 2011}}</ref> |

The carapace which shields the prosoma also bears two pairs of eyes – a pair of [[Simple eye in invertebrates|simple eyes]] at the front, and a pair of compound eyes positioned laterally. In common with other horseshoe crabs, ''T. gigas'' also has ventral eyes near the mouthparts, and [[photoreceptor protein|photoreceptors]] in the caudal spine.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/H/horseshoe_crab.html |title=Horseshoe crab |author=Liza Carruthers |work=The Internet Encyclopedia of Science |accessdate=January 22, 2011}}</ref> |

||

On its underside, ''T. gigas'' has seven pairs of legs, five of which bear small claws, and five pairs of [[book gill]]s, which are used for [[gas exchange]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marine.usf.edu/pjocean/packets/f01/f01u5p3.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]] |year=2001 |title=COAST / Horseshoe crabs |work=Project Oceanography |publisher=[[University of South Florida]] |pages=81–91}}</ref> |

On its underside, ''T. gigas'' has seven pairs of legs, five of which bear small claws, and five pairs of [[book gill]]s, which are used for [[gas exchange]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marine.usf.edu/pjocean/packets/f01/f01u5p3.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]] |year=2001 |title=COAST / Horseshoe crabs |work=Project Oceanography |publisher=[[University of South Florida]] |pages=81–91}}</ref> |

||

==Lifecycle== |

|||

| ⚫ | The [[biological life cycle|lifecycle]] of ''T. gigas'' is relatively long and involves a large number of [[instar]]s. The [[egg (biology)|eggs]] are about {{convert|3.7|mm|abbr=on}} in diameter.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Koichi Sekiguchi |author2=Hiroaki Sugita |lastauthoramp=yes |year=1980 |title=Systematics and hybridization in the four living species of horseshoe crabs |journal=[[Evolution (journal)|Evolution]] |volume=34 |issue=4 |pages=712–718 |jstor=2408025 |doi=10.2307/2408025}}</ref> The freshly hatched [[larva]]e, known as trilobite larvae, have no tail, and are {{convert|8|mm|abbr=on}} long.<ref>{{cite book |editor1=John T. Tanacredi |editor2=Mark L. Botton |editor3=David R. Smith |title=Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |isbn=978-0-387-89959-6 |author=J. K. Mishra |year=2009 |chapter=Larval culture of ''Tachypleus gigas'' and its molting behavior under laboratory conditions |pages=513–519 |doi=10.1007/978-0-387-89959-6_32}}</ref> Males are thought to pass through 12 [[ecdysis|moults]] before reaching [[sexual maturity]], while females pass through 13 moults.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Koichi Sekiguchi |author2=Hidehiro Seshimo |author3=Hiroaki Sugita |lastauthoramp=yes |year=1988 |title=Post-embryonic development of the horseshoe crab |journal=[[Biological Bulletin]] |volume=174 |issue=3 |pages=337–345 |url=http://www.biolbull.org/cgi/content/abstract/174/3/337 |doi=10.2307/1541959}}</ref> |

||

==Distribution and habitat== |

==Distribution and habitat== |

||

| Line 36: | Line 33: | ||

==Behavior, ecology and conservation== |

==Behavior, ecology and conservation== |

||

| ⚫ | The [[biological life cycle|lifecycle]] of ''T. gigas'' is relatively long and involves a large number of [[instar]]s. The [[egg (biology)|eggs]] are about {{convert|3.7|mm|abbr=on}} in diameter.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Koichi Sekiguchi |author2=Hiroaki Sugita |lastauthoramp=yes |year=1980 |title=Systematics and hybridization in the four living species of horseshoe crabs |journal=[[Evolution (journal)|Evolution]] |volume=34 |issue=4 |pages=712–718 |jstor=2408025 |doi=10.2307/2408025}}</ref> The freshly hatched [[larva]]e, known as trilobite larvae, have no tail, and are {{convert|8|mm|abbr=on}} long.<ref>{{cite book |editor1=John T. Tanacredi |editor2=Mark L. Botton |editor3=David R. Smith |title=Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |isbn=978-0-387-89959-6 |author=J. K. Mishra |year=2009 |chapter=Larval culture of ''Tachypleus gigas'' and its molting behavior under laboratory conditions |pages=513–519 |doi=10.1007/978-0-387-89959-6_32}}</ref> Males are thought to pass through 12 [[ecdysis|moults]] before reaching [[sexual maturity]], while females pass through 13 moults.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Koichi Sekiguchi |author2=Hidehiro Seshimo |author3=Hiroaki Sugita |lastauthoramp=yes |year=1988 |title=Post-embryonic development of the horseshoe crab |journal=[[Biological Bulletin]] |volume=174 |issue=3 |pages=337–345 |url=http://www.biolbull.org/cgi/content/abstract/174/3/337 |doi=10.2307/1541959}}</ref> |

||

The diet of ''T. gigas'' is chiefly composed of [[Mollusca|molluscs]], [[detritus]], and [[polychaete]]s, which it seeks on the ocean floor.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Anil Chatterji |author2=J. K. Mishra |author3=A. H. Parulekar |last-author-amp=yes |year=1992 |title=Feeding behaviour and food selection in the horseshoe crab, ''Tachypleus gigas'' (Müller) |journal=[[Hydrobiologia]] |volume=246 |issue=1 |pages=41–48 |doi=10.1007/BF00005621}}</ref> [[House crow]]s have been observed to turn ''T. gigas'' over and eat the soft underside, while [[gull]]s only attack individuals that are already stranded upside-down.<ref name="Food web"/> |

The diet of ''T. gigas'' is chiefly composed of [[Mollusca|molluscs]], [[detritus]], and [[polychaete]]s, which it seeks on the ocean floor.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Anil Chatterji |author2=J. K. Mishra |author3=A. H. Parulekar |last-author-amp=yes |year=1992 |title=Feeding behaviour and food selection in the horseshoe crab, ''Tachypleus gigas'' (Müller) |journal=[[Hydrobiologia]] |volume=246 |issue=1 |pages=41–48 |doi=10.1007/BF00005621}}</ref> [[House crow]]s have been observed to turn ''T. gigas'' over and eat the soft underside, while [[gull]]s only attack individuals that are already stranded upside-down.<ref name="Food web"/> |

||

Since horseshoe crabs do not moult after they have reached |

Since horseshoe crabs do not moult after they have reached sexual maturity, they are often colonised by [[epibiont]]s.<ref name="Patil"/> The dominant [[diatom]]s are species of the genera ''[[Navicula]]'', ''[[Nitzschia]]'', and ''[[Skeletonema]]''.<ref name="Patil"/> Among the larger organisms, the [[sea anemone]] ''[[Metridium]]'', the [[bryozoa]]n ''[[Membranipora]]'', the [[barnacle]] ''[[Balanus amphitrite]]'', and the [[Bivalvia|bivalves]] ''[[Anomia (bivalve)|Anomia]]'' and ''[[Crassostrea]]'' are the most frequent colonists of ''T. gigas''.<ref name="Patil"/> Rarer epibionts include [[green algae]], [[flatworm]]s, [[tunicate]]s, [[Isopoda|isopods]], [[Amphipoda|amphipods]], [[gastropod]]s, [[mussel]]s, [[pelecypod]]s, [[annelid]]s, and [[polychaete]]s.<ref name="Patil"/> |

||

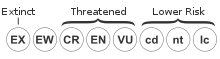

''T. gigas'' is listed as [[Data Deficient]] on the [[IUCN Red List]].<ref name="IUCN">{{Cite journal | author = World Conservation Monitoring Centre | author-link = World Conservation Monitoring Centre | title = ''Tachypleus gigas'' | journal = [[The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species]] | volume = 1996 | page = e.T21308A9266907 | publisher = [[IUCN]] | date = 1996 | url = http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/21308/0 | doi = 10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T21308A9266907.en | access-date = 9 January 2018}}</ref> |

''T. gigas'' is listed as [[Data Deficient]] on the [[IUCN Red List]].<ref name="IUCN">{{Cite journal | author = World Conservation Monitoring Centre | author-link = World Conservation Monitoring Centre | title = ''Tachypleus gigas'' | journal = [[The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species]] | volume = 1996 | page = e.T21308A9266907 | publisher = [[IUCN]] | date = 1996 | url = http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/21308/0 | doi = 10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T21308A9266907.en | access-date = 9 January 2018}}</ref> |

||

| Line 47: | Line 46: | ||

''T. gigas'' is estimated to have [[speciation|diverged]] from the other Asian species of horseshoe crab {{Ma|52.5}}.<ref>{{cite book |editor1=R. Alan B. Ezekowitz |editor2=Jules Hoffmann |year=2003 |title=Innate Immunity |publisher=[[Humana Press]] |isbn=978-1-58829-046-5 |author1=Shun-ichiro Kawabata |author2=Tsukasa Osaki |author3=Sadaaki Iwanaga |lastauthoramp=yes |chapter=Innate immunity in the horseshoe crab |pages=109–125 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xo508yZcnacC&pg=PA109}}</ref> While it is clear that the American horseshoe crab ''[[Limulus polyphemus]]'' is distinct from the remaining extant species of horseshoe crab, relationships within the Asian horseshoe crabs remains uncertain.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Xuhua Xia |year=2000 |title=Phylogenetic relationship among horseshoe crab species: effect of substitution models on phylogenetic analyses |journal=[[Systematic Biology]] |volume=49 |issue=1 |pages=87–100 |doi=10.1080/10635150050207401 |pmid=12116485 |jstor=2585308}}</ref> ''T. gigas'' has a [[chromosome number]] of 2''n'' = 28, compared to 26 in ''T. tridentatus'', 32 in ''Carcinoscorpius'', and 52 in ''Limulus''.<ref>{{cite book |editor1=Carl N. Shuster Jr. |editor2=Robert B. Barlow |editor3=H. Jane Brockmann |year=2003 |title=The American Horseshoe Crab |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=978-0-674-01159-5 |author1=Carl N. Schuster Jr. |author2=Koichi Sekiguchi |lastauthoramp=yes |chapter=Growing up takes about ten years and eighteen stages |pages=103–132 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0OSAKny-6M4C&pg=PA113}}</ref> |

''T. gigas'' is estimated to have [[speciation|diverged]] from the other Asian species of horseshoe crab {{Ma|52.5}}.<ref>{{cite book |editor1=R. Alan B. Ezekowitz |editor2=Jules Hoffmann |year=2003 |title=Innate Immunity |publisher=[[Humana Press]] |isbn=978-1-58829-046-5 |author1=Shun-ichiro Kawabata |author2=Tsukasa Osaki |author3=Sadaaki Iwanaga |lastauthoramp=yes |chapter=Innate immunity in the horseshoe crab |pages=109–125 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xo508yZcnacC&pg=PA109}}</ref> While it is clear that the American horseshoe crab ''[[Limulus polyphemus]]'' is distinct from the remaining extant species of horseshoe crab, relationships within the Asian horseshoe crabs remains uncertain.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Xuhua Xia |year=2000 |title=Phylogenetic relationship among horseshoe crab species: effect of substitution models on phylogenetic analyses |journal=[[Systematic Biology]] |volume=49 |issue=1 |pages=87–100 |doi=10.1080/10635150050207401 |pmid=12116485 |jstor=2585308}}</ref> ''T. gigas'' has a [[chromosome number]] of 2''n'' = 28, compared to 26 in ''T. tridentatus'', 32 in ''Carcinoscorpius'', and 52 in ''Limulus''.<ref>{{cite book |editor1=Carl N. Shuster Jr. |editor2=Robert B. Barlow |editor3=H. Jane Brockmann |year=2003 |title=The American Horseshoe Crab |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=978-0-674-01159-5 |author1=Carl N. Schuster Jr. |author2=Koichi Sekiguchi |lastauthoramp=yes |chapter=Growing up takes about ten years and eighteen stages |pages=103–132 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0OSAKny-6M4C&pg=PA113}}</ref> |

||

[[Common name]]s for the species include Indo-Pacific horseshoe crab,<ref name="Food web">{{cite book |editor1=Carl N. Shuster Jr. |editor2=Robert B. Barlow |editor3=H. Jane Brockmann |year=2003 |title=The American Horseshoe Crab |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=978-0-674-01159-5 |author=Mark L. Bolton |author2=Carl N. Schuster Jr. with John A. Keinath |last-author-amp=yes |chapter=Horseshoe crabs in a food web: who eats whom? |pages=133–153 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0OSAKny-6M4C&pg=PA138}}</ref> Indonesian horseshoe crab,<ref>{{cite book |editor1=Carl N. Shuster Jr. |editor2=Robert B. Barlow |editor3=H. Jane Brockmann |year=2003 |title=The American Horseshoe Crab |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=978-0-674-01159-5 |author1=Louis Leibovitz |author2=Gregory A. Lewbart |lastauthoramp=yes |chapter=Diseases and symbionts: vulnerability despite tough shells |pages=245–275 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0OSAKny-6M4C&pg=PA265}}</ref> Indian horseshoe crab<ref>{{cite book |editor=John T. Tanacredi |year=2001 |title=''Limulus'' in the Limelight: a Species 350 Million Years in the Making and in Peril? |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |isbn=978-0-306-46681-6 |author=Mark L. Botton |chapter=The conservation of horseshoe crabs: what can we learn from the Japanese experience? |pages=41–52 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CJiybSNmo7YC&pg=PA42}}</ref> and Chinese horseshoe crab.<ref>{{cite book |editor=John T. Tanacredi |year=2001 |title=''Limulus'' in the Limelight: a Species 350 Million Years in the Making and in Peril? |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |isbn=978-0-306-46681-6 |author=Carl N. Schuster Jr. |chapter=Two perspectives: horseshoe crabs during 420 million years worldwide, and the past 150 years in Delaware Bay |pages=17–40 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CJiybSNmo7YC&pg=PA25}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 00:39, 27 June 2018

| Tachypleus gigas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | T. gigas

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tachypleus gigas (Müller, 1785)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Tachypleus gigas, commonly known as the Indo-Pacific horseshoe crab,[2] Indonesian horseshoe crab,[3] Indian horseshoe crab,[4] or southern horseshoe crab,[5] is one of the four extant (living) species of horseshoe crab. It is found in coastal water in South and Southeast Asia at depths to 40 m (130 ft).[1] It grows up to about 50 cm (20 in) long, including the tail, and is covered by a sturdy carapace that is up to about 26.5 cm (10.4 in) wide.[6]

Description

T. gigas has a "sage green" chitinous exoskeleton.[7] Despite the scientific name T. gigas, the close relative Tachypleus tridentatus reaches a larger size. Both are considerably larger than Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda.[8] Like the other species, females of T. gigas grow larger than males. On average, females are about 42 cm (17 in) long, including a tail (telson) that is about 20 cm (7.9 in), and their carapace (prosoma) is about 22 cm (8.7 in) wide. In comparison, the average for males is about 34 cm (13 in) long, including a tail that is about 17.5 cm (6.9 in), and their carapace is about 17.5 cm (6.9 in) wide.[6] The largest females reach a total length of more than 50 cm (20 in) and can weigh more than 1.8 kg (4.0 lb).[6] In addition to their smaller size, males have a paler and rougher carapace, and act as hosts to a greater number of epibionts.[7] The tail bears a crest dorsally and is concave ventrally.[1] The anterior part of the tail is sharply serrated.[9]

The carapace which shields the prosoma also bears two pairs of eyes – a pair of simple eyes at the front, and a pair of compound eyes positioned laterally. In common with other horseshoe crabs, T. gigas also has ventral eyes near the mouthparts, and photoreceptors in the caudal spine.[10]

On its underside, T. gigas has seven pairs of legs, five of which bear small claws, and five pairs of book gills, which are used for gas exchange.[11]

Distribution and habitat

T. gigas is one of three living species of horseshoe crabs in Asia, the others being Tachypleus tridentatus and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda. The fourth living species, Limulus polyphemus, is found in the Americas.[8] T. gigas is found in tropical South and Southeast Asia, ranging from the Andaman Sea to the South China Sea,[12] with records from India, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines.[13][14] Although records are lacking, it likely also occurs in Myanmar.[14]

T. gigas inhabits sandy and muddy shores[9] at depths to 40 m (130 ft),[1] and is the only horseshoe crab to have been observed swimming at the surface of the ocean.[15] It occurs in both marine and brackish waters in salinities down to 15 PSU, but their eggs only hatch above 20 PSU.[14]

Behavior, ecology and conservation

The lifecycle of T. gigas is relatively long and involves a large number of instars. The eggs are about 3.7 mm (0.15 in) in diameter.[16] The freshly hatched larvae, known as trilobite larvae, have no tail, and are 8 mm (0.31 in) long.[17] Males are thought to pass through 12 moults before reaching sexual maturity, while females pass through 13 moults.[18]

The diet of T. gigas is chiefly composed of molluscs, detritus, and polychaetes, which it seeks on the ocean floor.[19] House crows have been observed to turn T. gigas over and eat the soft underside, while gulls only attack individuals that are already stranded upside-down.[2]

Since horseshoe crabs do not moult after they have reached sexual maturity, they are often colonised by epibionts.[7] The dominant diatoms are species of the genera Navicula, Nitzschia, and Skeletonema.[7] Among the larger organisms, the sea anemone Metridium, the bryozoan Membranipora, the barnacle Balanus amphitrite, and the bivalves Anomia and Crassostrea are the most frequent colonists of T. gigas.[7] Rarer epibionts include green algae, flatworms, tunicates, isopods, amphipods, gastropods, mussels, pelecypods, annelids, and polychaetes.[7]

T. gigas is listed as Data Deficient on the IUCN Red List.[13]

Taxonomy

Tachypleus gigas was first described by Otto Friedrich Müller in 1785. It was originally placed in the genus Limulus, but was transferred to the genus Tachypleus by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1902.[1]

T. gigas is estimated to have diverged from the other Asian species of horseshoe crab 52.5 million years ago.[20] While it is clear that the American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus is distinct from the remaining extant species of horseshoe crab, relationships within the Asian horseshoe crabs remains uncertain.[21] T. gigas has a chromosome number of 2n = 28, compared to 26 in T. tridentatus, 32 in Carcinoscorpius, and 52 in Limulus.[22]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e S. Lazarus; V. Narayana Pillai; P. Devadoss; G. Mohanraj (1990). "Occurrence of king crab, Tachypleus gigas (Muller), off the northeast coast of India" (PDF). Proceedings of the first workshop on scientific results of FORV Sagar Sampada, 5–7 June 1989, Kochi: 393–395.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mark L. Bolton; Carl N. Schuster Jr. with John A. Keinath (2003). "Horseshoe crabs in a food web: who eats whom?". In Carl N. Shuster Jr.; Robert B. Barlow; H. Jane Brockmann (eds.). The American Horseshoe Crab. Harvard University Press. pp. 133–153. ISBN 978-0-674-01159-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Louis Leibovitz; Gregory A. Lewbart (2003). "Diseases and symbionts: vulnerability despite tough shells". In Carl N. Shuster Jr.; Robert B. Barlow; H. Jane Brockmann (eds.). The American Horseshoe Crab. Harvard University Press. pp. 245–275. ISBN 978-0-674-01159-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Mark L. Botton (2001). "The conservation of horseshoe crabs: what can we learn from the Japanese experience?". In John T. Tanacredi (ed.). Limulus in the Limelight: a Species 350 Million Years in the Making and in Peril?. Springer. pp. 41–52. ISBN 978-0-306-46681-6.

- ^ "Identification guide". Horseshoe Crab monitoring site. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ a b c A. Raman Noor Jawahir; Mohamad Samsur; Mohd L. Shabdin; Khairul-Adha A. Rahim (2017). "Morphometric allometry of horseshoe crab, Tachypleus gigas at west part of Sarawak waters, Borneo, East Malaysia". AACL Bioflux. 10 (1): 18–24.

- ^ a b c d e f J. S. Patil; A. C. Anil (2000). "Epibiotic community of the horseshoe crab Tachypleus gigas". Marine Biology. 136 (4): 699–713. doi:10.1007/s002270050730.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "About the Species". The Horseshoe Crab. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ a b P. Gopalakrishnakone (1990). "Class Merostomata". A Colour Guide to Dangerous Animals. NUS Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-9971-69-150-9.

- ^ Liza Carruthers. "Horseshoe crab". The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ "COAST / Horseshoe crabs" (PDF). Project Oceanography. University of South Florida. 2001. pp. 81–91.

- ^ "Tachypleus gigas (Müller, 1785)". Horseshoe Crab monitoring site. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ a b World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Tachypleus gigas". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996. IUCN: e.T21308A9266907. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T21308A9266907.en. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Stine Vestbo; Matthias Obst; Francisco J. Quevedo Fernandez; Itsara Intanai; Peter Funch (2018). "Present and Potential Future Distributions of Asian Horseshoe Crabs Determine Areas for Conservation". Frontiers in Marine Science. 5 (164): 1-16. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00164.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Carl N. Schuster Jr.; Lyall I. Anderson (2003). "A history of skeletal structure: clues to relationships among species". In Carl N. Shuster Jr.; Robert B. Barlow; H. Jane Brockmann (eds.). The American Horseshoe Crab. Harvard University Press. pp. 154–188. ISBN 978-0-674-01159-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Koichi Sekiguchi; Hiroaki Sugita (1980). "Systematics and hybridization in the four living species of horseshoe crabs". Evolution. 34 (4): 712–718. doi:10.2307/2408025. JSTOR 2408025.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ J. K. Mishra (2009). "Larval culture of Tachypleus gigas and its molting behavior under laboratory conditions". In John T. Tanacredi; Mark L. Botton; David R. Smith (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Springer. pp. 513–519. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-89959-6_32. ISBN 978-0-387-89959-6.

- ^ Koichi Sekiguchi; Hidehiro Seshimo; Hiroaki Sugita (1988). "Post-embryonic development of the horseshoe crab". Biological Bulletin. 174 (3): 337–345. doi:10.2307/1541959.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Anil Chatterji; J. K. Mishra; A. H. Parulekar (1992). "Feeding behaviour and food selection in the horseshoe crab, Tachypleus gigas (Müller)". Hydrobiologia. 246 (1): 41–48. doi:10.1007/BF00005621.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Shun-ichiro Kawabata; Tsukasa Osaki; Sadaaki Iwanaga (2003). "Innate immunity in the horseshoe crab". In R. Alan B. Ezekowitz; Jules Hoffmann (eds.). Innate Immunity. Humana Press. pp. 109–125. ISBN 978-1-58829-046-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Xuhua Xia (2000). "Phylogenetic relationship among horseshoe crab species: effect of substitution models on phylogenetic analyses". Systematic Biology. 49 (1): 87–100. doi:10.1080/10635150050207401. JSTOR 2585308. PMID 12116485.

- ^ Carl N. Schuster Jr.; Koichi Sekiguchi (2003). "Growing up takes about ten years and eighteen stages". In Carl N. Shuster Jr.; Robert B. Barlow; H. Jane Brockmann (eds.). The American Horseshoe Crab. Harvard University Press. pp. 103–132. ISBN 978-0-674-01159-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)