Do not resuscitate: Difference between revisions

rv |

Reference edited with ProveIt - Basis for choosing DNR was implicit: made it explicit and updated numbers. Made lede more neutral internationally |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Do Not Resuscitate''' ('''DNR'''), also known as '''no code''' or '''allow natural death''', is a legal order written |

'''Do Not Resuscitate''' ('''DNR'''), also known as '''no code''' or '''allow natural death''', is a legal order, written or oral depending on country, to withhold [[cardiopulmonary resuscitation]] (CPR) or [[advanced cardiac life support]] (ACLS) in case their [[Asystole|heart were to stop]] or they were to [[Apnea|stop breathing]]. Many countries do not allow a DNR order. In most countries which do, the order is made by a doctor. In some coutries this is based on the wishes of the patient or health care [[power of attorney]].<ref name="weil">{{Cite journal |last=Weil |first=Max Harry |last2=Gullo |first2=Antonino |last3=Ristagno |first3=Giuseppe |last4=Santonocito |first4=Cristina |date=2013-02-01 |title=Do-not-resuscitate order: a view throughout the world |url=https://www.annalsthoracicsurgery.org/article/S0883-9441(12)00224-9/abstract |journal=Journal of Critical Care |language=English |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=14–21 |doi=10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.07.005 |issn=1557-8615 |pmid=22981534}}</ref> |

||

In the health care community, [[allow natural death]] (AND) is a term that is quickly gaining favor as it focuses on what is being done, not what is being avoided.{{citation needed|date=October 2014}} Some criticize the term "do not resuscitate" because of the implication of treatment being withheld. US research shows that about 16% of patients who require CPR outside the hospital and 26% of patients who require CPR while in the hospital survive to be discharged from the hospital alive. Patients who are over 80, live in nursing homes, have serious medical problems, or who have cancer, are slightly less likely to survive. |

|||

A DNR |

A DNR is not intended to affect any treatment other than that which would require [[tracheal intubation|intubation]] or [[CPR]]. Patients who are DNR can continue to get chemotherapy, antibiotics, dialysis, or any other appropriate treatments. |

||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

{{TOC limit|3}} |

||

| Line 32: | Line 33: | ||

Until recently in the UK it was common to write "Not for 222" or conversationally, "Not for twos." This was implicitly a hospital DNR order, where 222 (or similar) is the hospital telephone number for the emergency resuscitation or crash team.{{Citation needed|date=July 2011}} |

Until recently in the UK it was common to write "Not for 222" or conversationally, "Not for twos." This was implicitly a hospital DNR order, where 222 (or similar) is the hospital telephone number for the emergency resuscitation or crash team.{{Citation needed|date=July 2011}} |

||

==Basis for choice== |

|||

There is little literature on why some patients choose DNR and others choose CPR. In the 1990s there was an understanding that old people would not survive CPR or would become mentally disabled.<ref name="hooyer">{{Cite journal |last=Hooyer |first=C. |last2=Schonwetter |first2=R. S. |last3=Van |first3=C. Engen |last4=Bezemer |first4=P. D. |last5=Duursma |first5=S. A. |last6=Dautzenberg |first6=P. L. |date=1993-08-01 |title=Resuscitation decisions on a Dutch geriatric ward. |url=http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/8210310 |journal=The Quarterly journal of medicine |volume=86 |issue=8 |pages=535–542 |issn=0033-5622 |pmid=8210310}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="vanmil">{{Cite journal |last=van Mil |first=Annette H.M. |last2=van Klink |first2=Rik C.J. |last3=Huntjens |first3=Christine |last4=Westendorp |first4=Rudi G.J. |last5=Stiggelbout |first5=Anne M. |last6=Meinders |first6=A.Edo |last7=Lagaay |first7=A. Margot |date=2000-10-01 |title=Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Preferences in Dutch Community-dwelling and Hospitalized Elderly People: An Interaction between Gender and Quality of Life |url=https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X0002000406 |journal=Medical Decision Making |language=en |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=423–429 |doi=10.1177/0272989X0002000406 |issn=0272-989X}}</ref> |

|||

'''Survival rates''' have risen, even among the very old and sick, and are expected to rise further, as the best practices spread, and improvements are found.<ref name="goal">{{Cite web |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171008151726/http://www.heart.org:80/HEARTORG/General/Emergency-Cardiovascular-Care-2020-Impact-Goals_UCM_435128_Article.jsp |title=Emergency Cardiovascular Care 2020 Impact Goals |date=2017-10-08 |website=web.archive.org, American Heart Association |access-date=2018-12-12}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="cprheart">{{Cite web |url=https://cpr.heart.org/AHAECC/CPRAndECC/AboutCPRFirstAid/UCM_473210_About-CPR-ECC.jsp |title=About CPR & ECC |website=cpr.heart.org |access-date=2018-12-12}}</ref> |

|||

In US hospitals in 2016, 26% of patients who recieved CPR survived to hospital discharge.<ref name="2018update">{{Cite journal |last=Benjamin Emelia J. |last2=Virani Salim S. |last3=Callaway Clifton W. |last4=Chamberlain Alanna M. |last5=Chang Alexander R. |last6=Cheng Susan |last7=Chiuve Stephanie E. |last8=Cushman Mary |last9=Delling Francesca N. |date=2018-03-20 |title=Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association |url=https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 |journal=Circulation |volume=137 |issue=12 |pages=e67–e492 |doi=10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558}}</ref> |

|||

64% of attempts caused a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC, most recent data are 2014),<ref name="girotra-race">{{Cite journal |last=Girotra |first=Saket |last2=Vaughan-Sarrazin |first2=Mary |last3=Jones |first3=Philip G. |last4=Graham |first4=Garth |last5=Zhou |first5=Yunshu |last6=Bradley |first6=Steven M. |last7=Chan |first7=Paul S. |last8=Joseph |first8=Lee |date=2017-09-01 |title=Temporal Changes in the Racial Gap in Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest |url=https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2647084 |journal=JAMA Cardiology |language=en |volume=2 |issue=9 |pages=976–984 |doi=10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2403 |issn=2380-6583}}</ref> |

|||

In 2017 in the US, outside hospitals, 16% of people whose cardiac arrest was witnessed survived to hospital discharge. 43% gained ROSC, and 38% survived to hospital admission.<ref name="mycares">{{Cite web |url=https://mycares.net/sitepages/reports.jsp |title=National Reports by Year « MyCares |website=mycares.net |access-date=2018-12-12}}</ref> |

|||

Even among very sick patients at least 10% survive: A study of CPR in a sample of US hospitals from 2001 to 2010,<ref name="merchant">{{Cite journal |last=Merchant |first=Raina M. |last2=Berg |first2=Robert A. |last3=Yang |first3=Lin |last4=Becker |first4=Lance B. |last5=Groeneveld |first5=Peter W. |last6=Chan |first6=Paul S. |last7=Investigators |first7=for the American Heart Association's Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation |date=2014-01-31 |title=Hospital Variation in Survival After In‐hospital Cardiac Arrest |url=https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/jaha.113.000400 |journal=Journal of the American Heart Association |language=EN |access-date=2018-12-12 }}</ref> |

|||

where overall survival was 19%, found 10% survival among cancer patients, 12% among dialysis patients, 14% over age 80, 15% among blacks, 17% for patients who lived in nursing homes, 19% for patients with heart failure, and 25% for patients with heart monitoring outside the ICU, so there is room for good practices to spread, raising the averages. An earlier study of Medicare patients in hospitals 1992-2006, where overall survival was 18%, found 13% survival in the poorest neighborhoods.<ref name="ehlenbach">{{Cite journal |last=Ehlenbach |first=William J. |last2=Barnato |first2=Amber E. |last3=Curtis |first3=J. Randall |last4=Kreuter |first4=William |last5=Koepsell |first5=Thomas D. |last6=Deyo |first6=Richard A. |last7=Stapleton |first7=Renee D. |date=2009-07-02 |title=Epidemiologic Study of In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in the Elderly |url=https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810245 |journal=New England Journal of Medicine |volume=361 |issue=1 |pages=22–31 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0810245 |issn=0028-4793 |pmc=PMC2917337 |pmid=19571280}}</ref> |

|||

An earlier study of US hospitals 1992-2005 found 18% survived to hospital discharge, again with variations among types of patients.<ref>{{cite journal | pmid = 19571280 | doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0810245 | volume=361 | issue=1 | title=Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly | pmc=2917337 |date=July 2009 |vauthors=Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, etal | journal=N. Engl. J. Med. | pages=22–31}}</ref> |

|||

Since 2003, widespread cooling of patients after CPR<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1161/01.CIR.0000079019.02601.90 |title=Therapeutic Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest: An Advisory Statement by the Advanced Life Support Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation |year=2003 |last1=Nolan |first1=J.P. |journal=Circulation |volume=108 |pages=118–21 |pmid=12847056 |last2=Morley |first2=PT |last3=Vanden Hoek |first3=TL |last4=Hickey |first4=RW |last5=Kloeck |first5=WG |last6=Billi |first6=J |last7=Böttiger |first7=BW |last8=Morley |first8=PT |last9=Nolan |first9=JP |last10=Okada |first10=K |last11=Reyes |first11=C |last12=Shuster |first12=M |last13=Steen |first13=PA |last14=Weil |first14=MH |last15=Wenzel |first15=V |last16=Hickey |first16=RW |last17=Carli |first17=P |last18=Vanden Hoek |first18=TL |last19=Atkins |first19=D |author20=International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation |issue=1}}</ref> |

|||

and other improvements have raised survival and reduced mental disabilities. |

|||

'''Organ donation''' is not usually possible after a death with a DNR, but it is after CPR. If the patient dies before discharge, ROSC allows all organs to be considered for donation. If the patient does not achieve ROSC, and CPR continues until an operating room is available, the kidneys and liver can still be considered for donation.<ref name="ecc">{{Cite journal |date=2015 |title=Part 8: Post-Cardiac Arrest Care – ECC Guidelines |url=https://eccguidelines.heart.org/index.php/circulation/cpr-ecc-guidelines-2/part-8-post-cardiac-arrest-care/?strue=1&id=11 |journal=Resuscitation Science, section 11 |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

1,000 organs per year in the US are transplanted from patients who had CPR.<ref name="orioles">{{Cite journal |last=Orioles |first=Alberto |last2=Morrison |first2=Wynne E. |last3=Rossano |first3=Joseph W. |last4=Shore |first4=Paul M. |last5=Hasz |first5=Richard D. |last6=Martiner |first6=Amy C. |last7=Berg |first7=Robert A. |last8=Nadkarni |first8=Vinay M. |date=2013-12-01 |title=An under-recognized benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation: organ transplantation |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23949474 |journal=Critical Care Medicine |volume=41 |issue=12 |pages=2794–2799 |doi=10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829a7202 |issn=1530-0293 |pmid=23949474}}</ref> |

|||

Donations can be taken from 40% of patients who have ROSC and later become brain dead,<ref name="sandroni">{{Cite journal |last=Sandroni |first=Claudio |last2=D’Arrigo |first2=Sonia |last3=Callaway |first3=Clifton W. |last4=Cariou |first4=Alain |last5=Dragancea |first5=Irina |last6=Taccone |first6=Fabio Silvio |last7=Antonelli |first7=Massimo |date=2016 |title=The rate of brain death and organ donation in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5069310/ |journal=Intensive Care Medicine |volume=42 |issue=11 |pages=1661–1671 |doi=10.1007/s00134-016-4549-3 |issn=0342-4642 |pmc=PMC5069310 |pmid=27699457}}</ref> |

|||

and an average of 3 organs are taken from each patient who donates organs.<ref name="orioles"/> |

|||

DNR does not usually allow organ donation. |

|||

'''Mental abilities''' can decline if the brain lacks blood for long, but hospital patients usually keep about the same mental abilities after CPR, based on before and after measurement of their Cerebral-Performance Category (CPC) codes in a 2000-2009 study.<ref name="girotra-supp">{{Cite journal |last=Girotra |first=S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Li Y, Krumholz HM, Chan PS. |date=2012 |title=Supplementary Appendix to "Trends in survival after inhospital cardiac arrest" |url= https://www.nejm.org/doi/suppl/10.1056/NEJMoa1109148/suppl_file/nejmoa1109148_appendix.pdf |journal=NEJM |pages=17}}</ref> |

|||

For CPR outside hospitals there are no before and after studies, but 3% of patients had severe mental problems at discharge.<ref name="2018update"/> |

|||

Mental abilities can continue to improve in the six months after discharge.<ref name="hirsch">{{Cite journal |last=Hirsch |first=K. G. |last2=Albers |first2=G. W. |last3=Mlynash |first3=M. |last4=Eyngorn |first4=I. |last5=Tong |first5=J. T. |date=2016-12-01 |title=Functional Neurologic Outcomes Change Over the First Six Months after Cardiac Arrest, Functional Neurologic Outcomes Change Over the First 6 Months After Cardiac Arrest. |url=https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC5115936/ |journal=Critical care medicine, Critical care medicine |volume=44, 44 |issue=12, 12 |pages=e1202, e1202–e1207 |doi=10.1097/CCM.0000000000001963 |issn=0090-3493 |pmid=27495816}}</ref> |

|||

'''Side effects''' of CPR vary. The most common is vomiting, which necessitates clearing the mouth so patients do not breathe it in.<ref name="wash">{{Cite web |url=http://depts.washington.edu/learncpr/comp.html |title=CPR - you CAN do it! |website=depts.washington.edu |access-date=2018-12-12}}</ref> |

|||

Broken ribs are present in 3% (2009-12 data)<ref name="boland">{{Cite journal |last=Boland |first=Lori L. |last2=Satterlee |first2=Paul A. |last3=Hokanson |first3=Jonathan S. |last4=Strauss |first4=Craig E. |last5=Yost |first5=Dana |date= January-March 2015|title=Chest Compression Injuries Detected via Routine Post-arrest Care in Patients Who Survive to Admission after Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25076024 |journal=Prehospital emergency care: official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors |volume=19 |issue=1 |pages=23–30 |doi=10.3109/10903127.2014.936636 |issn=1545-0066 |pmid=25076024}}</ref> |

|||

to 8% (1997-99)<ref name="oschatz">{{Cite journal |last=Oschatz |first=E. |last2=Wunderbaldinger |first2=P. |last3=Sterz |first3=F. |last4=Holzer |first4=M. |last5=Kofler |first5=J. |last6=Slatin |first6=H. |last7=Janata |first7=K. |last8=Eisenburger |first8=P. |last9=Bankier |first9=A. A. |date=2001-07-01 |title=Cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed by bystanders does not increase adverse effects as assessed by chest radiography |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11429353 |journal=Anesthesia and Analgesia |volume=93 |issue=1 |pages=128–133 |issn=0003-2999 |pmid=11429353}}</ref> |

|||

of those who survive to hospital discharge, and 15% (2009-12) of those who die in the hospital. Those who died had needed longer periods of CPR, which may explain both deaths and fractures.<ref name="boland"/> |

|||

A study in the 1990s found 55% of CPR patients who died before discharge had broken ribs, and a study in the 1960s found 97% did; training and experience levels have improved.<ref name="hoke">{{Cite journal |last=Hoke |first=Robert, and Douglas Chamberlain |date=2004 |title=Skeletal chest injuries secondary to cardiopulmonary resuscitation |url=http://www.academia.edu/download/40919168/Resuscitation_2004_Hoke.pdf |journal=Resuscitation |volume=63 |pages=327-338}}</ref> |

|||

A 2004 overview said, "Chest injury is a price worth paying to achieve optimal efficacy of chest compressions. Cautious or faint-hearted chest compression may save bones in the individual case but not the patient’s life."<ref name="hoke"/> |

|||

The costal cartilage also breaks in an unknown number of additional cases, which can sound like breaking bones.<ref name="creighton">{{Cite web |url=http://heartsavercpromaha.com/cpr-review---keeping-it-real.html |title=CPR Review - Keeping It Real |website=HEARTSAVER (BLS Training Site) CPR/AED & First Aid (Bellevue, NE) |language=en |access-date=2018-12-12}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="emt">{{Cite web |url=http://emtlife.com/threads/cpr-breaking-bones.23116/ |title=CPR Breaking Bones |website=EMTLIFE |language=en-US |access-date=2018-12-12}}</ref> |

|||

'''POLST documents''' are the usual place where a DNR is recorded. A disability rights group criticizes the process, saying doctors are trained to offer very limited scenarios with no alternative treatments, and steer patients toward DNR. They also criticize that DNR orders are absolute, without variations for context.<ref name="coleman">{{Cite web |url=http://notdeadyet.org/full-written-public-comment-disability-related-concerns-about-polst |title=Full Written Public Comment: Disability Related Concerns About POLST |last=Coleman |first=Diane |date=2013-07-23 |website=Not Dead Yet |language=en-US |access-date=2018-12-12}}</ref> The Mayo Clinic found in 2013 that "Most patients with DNR/DNI [do not intubate] orders want CPR and/or intubation in hypothetical clinical scenarios," so the patients had not had enough explanation of the DNR/DNI or did not understand the explanation.<ref name="jesus">{{Cite journal |last=Jesus |first=John E. |last2=Allen |first2=Matthew B. |last3=Michael |first3=Glen E. |last4=Donnino |first4=Michael W. |last5=Grossman |first5=Shamai A. |last6=Hale |first6=Caleb P. |last7=Breu |first7=Anthony C. |last8=Bracey |first8=Alexander |last9=O'Connor |first9=Jennifer L. |date=2013-07-01 |title=Preferences for resuscitation and intubation among patients with do-not-resuscitate/do-not-intubate orders |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23809316 |journal=Mayo Clinic Proceedings |volume=88 |issue=7 |pages=658–665 |doi=10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.04.010 |issn=1942-5546 |pmid=23809316}}</ref> |

|||

'''Reductions in other care''' are not supposed to result from DNR, but they do. Patients with DNR are less likely to get medically appropriate care for a wide range of issues, and die sooner, even from causes unrelated to CPR. Many doctors construe DNR as a goal of not wanting full care, and do not even offer full care.<ref name="fendler">{{Cite journal |last=Fendler |first=Timothy |last2=Spertus |first2=John A. |last3=Kennedy |first3=Kevin |last4=Chen |first4=Lena M. |last5=Perman |first5=Sarah M. |last6=Chan |first6=Paul S. |date=2017-11-01 |title=Association Between Hospital Rates of Early Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Favorable Neurological Survival Among Survivors of In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5747564/ |journal=American heart journal |volume=193 |pages=108–116 |doi=10.1016/j.ahj.2017.05.017 |issn=0002-8703 |pmc=PMC5747564 |pmid=29129249}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="horwitz">{{Cite journal |last=Horwitz |first=Leora I. |date=2016-01-01 |title=Implications of Including Do-Not-Resuscitate Status in Hospital Mortality Measures |url=https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2474399 |journal=JAMA Internal Medicine |language=en |volume=176 |issue=1 |pages=105–106 |doi=10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6845 |issn=2168-6106}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="smith">{{Cite journal |last=Smith |first=Cardinale B. |last2=Bunch O'Neill |first2=Lynn |date=2008-10-01 |title=Do not resuscitate does not mean do not treat: how palliative care and other modalities can help facilitate communication about goals of care in advanced illness |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18828169 |journal=The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York |volume=75 |issue=5 |pages=460–465 |doi=10.1002/msj.20076 |issn=1931-7581 |pmid=18828169}}</ref> |

|||

'''After successful CPR''', hospitals often discuss putting the patient on DNR, to avoid another resuscitation. Guidelines generally call for a 72-hour wait to see what the prognosis is,<ref name="prognos">{{Cite journal |title=Part 3: Ethical Issues – ECC Guidelines, Timing of Prognostication in Post–Cardiac Arrest Adults - Updated |url=https://eccguidelines.heart.org/index.php/circulation/cpr-ecc-guidelines-2/part-3-ethical-issues/?strue=1&id=7-1 |journal=Resuscitation, item 7.1, "Prognostication" |language=en-US}}</ref> but within 12 hours US hospitals put up to 58% of survivors on DNR, with a median of 23% going DNR at this early stage, much earlier than the guideline. The hospitals putting fewest patients on DNR had more successful survival rates, which the researchers suggest shows their better care in general.<ref name="fendler"/> |

|||

When CPR happened outside the hospital, hospitals put up to 80% of survivors on DNR within 24 hours, with an average of 32.5%. These patients had less treatment, and almost all died in the hospital. The researchers say families need to expect death if they agree to DNR in the hospital.<ref name="richardson">{{Cite journal |last=Richardson |first=Derek K. |last2=Zive |first2=Dana |last3=Daya |first3=Mohamud |last4=Newgard |first4=Craig D. |date=2013-04-01 |title=The impact of early do not resuscitate (DNR) orders on patient care and outcomes following resuscitation from out of hospital cardiac arrest |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22940596 |journal=Resuscitation |volume=84 |issue=4 |pages=483–487 |doi=10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.327 |issn=1873-1570 |pmid=22940596}}</ref> |

|||

==Advance directive and living will== |

==Advance directive and living will== |

||

Revision as of 04:10, 12 December 2018

| Do not resuscitate | |

|---|---|

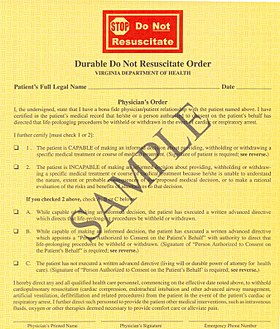

DNR form used in Virginia | |

| Other names | Do not attempt resuscitation, allow natural death, no code |

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR), also known as no code or allow natural death, is a legal order, written or oral depending on country, to withhold cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) in case their heart were to stop or they were to stop breathing. Many countries do not allow a DNR order. In most countries which do, the order is made by a doctor. In some coutries this is based on the wishes of the patient or health care power of attorney.[1] In the health care community, allow natural death (AND) is a term that is quickly gaining favor as it focuses on what is being done, not what is being avoided.[citation needed] Some criticize the term "do not resuscitate" because of the implication of treatment being withheld. US research shows that about 16% of patients who require CPR outside the hospital and 26% of patients who require CPR while in the hospital survive to be discharged from the hospital alive. Patients who are over 80, live in nursing homes, have serious medical problems, or who have cancer, are slightly less likely to survive.

A DNR is not intended to affect any treatment other than that which would require intubation or CPR. Patients who are DNR can continue to get chemotherapy, antibiotics, dialysis, or any other appropriate treatments.

Terminology

DNR and Do Not Resuscitate are common terms in the United States, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. This may be clarified in some regions with the addition of DNI (Do Not Intubate), although in some hospitals DNR alone will imply no intubation. Clinically, the vast majority of people requiring resuscitation will require intubation, making a DNI alone problematic. Hospitals sometimes use the expression no code, which refers to the jargon term code, short for Code Blue, an alert a hospital's resuscitation team.

Some areas of the United States and the United Kingdom include the letter A, as in DNAR, to clarify "Do Not Attempt Resuscitation." This alteration is so that it is not presumed by the patient or family that an attempt at resuscitation will be successful. Since the term DNR implies the omission of action, and therefore "giving up", some have advocated for these orders to be retermed Allow Natural Death.[2] New Zealand and Australia, and some hospitals in the UK, use the term NFR or Not For Resuscitation. Typically these abbreviations are not punctuated, e.g., DNR rather than D.N.R.

Resuscitation orders, or lack thereof, can also be referred to in the United States as a part of Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) or Medical Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) orders[3], typically created with input from next of kin when the patient or client is not able to communicate their wishes.

Another synonymous term is "not to be resuscitated" (NTBR).[4]

Until recently in the UK it was common to write "Not for 222" or conversationally, "Not for twos." This was implicitly a hospital DNR order, where 222 (or similar) is the hospital telephone number for the emergency resuscitation or crash team.[citation needed]

Basis for choice

There is little literature on why some patients choose DNR and others choose CPR. In the 1990s there was an understanding that old people would not survive CPR or would become mentally disabled.[5] [6]

Survival rates have risen, even among the very old and sick, and are expected to rise further, as the best practices spread, and improvements are found.[7] [8]

In US hospitals in 2016, 26% of patients who recieved CPR survived to hospital discharge.[9] 64% of attempts caused a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC, most recent data are 2014),[10] In 2017 in the US, outside hospitals, 16% of people whose cardiac arrest was witnessed survived to hospital discharge. 43% gained ROSC, and 38% survived to hospital admission.[11]

Even among very sick patients at least 10% survive: A study of CPR in a sample of US hospitals from 2001 to 2010,[12] where overall survival was 19%, found 10% survival among cancer patients, 12% among dialysis patients, 14% over age 80, 15% among blacks, 17% for patients who lived in nursing homes, 19% for patients with heart failure, and 25% for patients with heart monitoring outside the ICU, so there is room for good practices to spread, raising the averages. An earlier study of Medicare patients in hospitals 1992-2006, where overall survival was 18%, found 13% survival in the poorest neighborhoods.[13]

An earlier study of US hospitals 1992-2005 found 18% survived to hospital discharge, again with variations among types of patients.[14] Since 2003, widespread cooling of patients after CPR[15] and other improvements have raised survival and reduced mental disabilities.

Organ donation is not usually possible after a death with a DNR, but it is after CPR. If the patient dies before discharge, ROSC allows all organs to be considered for donation. If the patient does not achieve ROSC, and CPR continues until an operating room is available, the kidneys and liver can still be considered for donation.[16] 1,000 organs per year in the US are transplanted from patients who had CPR.[17] Donations can be taken from 40% of patients who have ROSC and later become brain dead,[18] and an average of 3 organs are taken from each patient who donates organs.[17] DNR does not usually allow organ donation.

Mental abilities can decline if the brain lacks blood for long, but hospital patients usually keep about the same mental abilities after CPR, based on before and after measurement of their Cerebral-Performance Category (CPC) codes in a 2000-2009 study.[19] For CPR outside hospitals there are no before and after studies, but 3% of patients had severe mental problems at discharge.[9] Mental abilities can continue to improve in the six months after discharge.[20]

Side effects of CPR vary. The most common is vomiting, which necessitates clearing the mouth so patients do not breathe it in.[21] Broken ribs are present in 3% (2009-12 data)[22] to 8% (1997-99)[23] of those who survive to hospital discharge, and 15% (2009-12) of those who die in the hospital. Those who died had needed longer periods of CPR, which may explain both deaths and fractures.[22] A study in the 1990s found 55% of CPR patients who died before discharge had broken ribs, and a study in the 1960s found 97% did; training and experience levels have improved.[24] A 2004 overview said, "Chest injury is a price worth paying to achieve optimal efficacy of chest compressions. Cautious or faint-hearted chest compression may save bones in the individual case but not the patient’s life."[24] The costal cartilage also breaks in an unknown number of additional cases, which can sound like breaking bones.[25] [26]

POLST documents are the usual place where a DNR is recorded. A disability rights group criticizes the process, saying doctors are trained to offer very limited scenarios with no alternative treatments, and steer patients toward DNR. They also criticize that DNR orders are absolute, without variations for context.[27] The Mayo Clinic found in 2013 that "Most patients with DNR/DNI [do not intubate] orders want CPR and/or intubation in hypothetical clinical scenarios," so the patients had not had enough explanation of the DNR/DNI or did not understand the explanation.[28]

Reductions in other care are not supposed to result from DNR, but they do. Patients with DNR are less likely to get medically appropriate care for a wide range of issues, and die sooner, even from causes unrelated to CPR. Many doctors construe DNR as a goal of not wanting full care, and do not even offer full care.[29] [30] [31]

After successful CPR, hospitals often discuss putting the patient on DNR, to avoid another resuscitation. Guidelines generally call for a 72-hour wait to see what the prognosis is,[32] but within 12 hours US hospitals put up to 58% of survivors on DNR, with a median of 23% going DNR at this early stage, much earlier than the guideline. The hospitals putting fewest patients on DNR had more successful survival rates, which the researchers suggest shows their better care in general.[29] When CPR happened outside the hospital, hospitals put up to 80% of survivors on DNR within 24 hours, with an average of 32.5%. These patients had less treatment, and almost all died in the hospital. The researchers say families need to expect death if they agree to DNR in the hospital.[33]

Advance directive and living will

Advance directives and living wills are documents written by individuals themselves, so as to state their wishes for care, if they are no longer able to speak for themselves. In contrast, it is a physician or hospital staff member who writes a DNR "physician's order," based upon the wishes previously expressed by the individual in his or her advance directive or living will. Similarly, at a time when the individual is unable to express his wishes, but has previously used an advance directive to appoint an agent, then a physician can write such a DNR "physician's order" at the request of that individual's agent. These various situations are clearly enumerated in the "sample" DNR order presented on this page.

It should be stressed that, in the United States, an advance directive or living will is not sufficient to ensure a patient is treated under the DNR protocol, even if it is their wish, as neither an advance directive nor a living will is a legally binding document.

Ethics

DNR orders in certain situations have been subject to ethical debate. In many institutions it is customary for a patient going to surgery to have their DNR automatically rescinded. Though the rationale for this may be valid, as outcomes from CPR in the operating room are substantially better than general survival outcomes after CPR, the impact on patient autonomy has been debated. It is suggested that facilities engage patients or their decision makers in a 'reconsideration of DNR orders' instead of automatically making a forced decision.[34]

There is accumulating evidence of a racial bias in DNR adoption. A 2014 study of end stage cancer patients found that non-Latino white patients were significantly more likely to have a DNR order (45%) than black (25%) and Latino (20%) patients. The correlation between preferences against life-prolonging care and the increased likelihood of advance care planning is consistent across ethnic groups.[35]

Ethical dilemmas occur when a patient with a DNR attempts suicide and the necessary treatment involves ventilation or CPR. In these cases it has been argued that the principle of beneficence takes precedence over patient autonomy and the DNR can be revoked by the physician.[36] Another dilemma occurs when a medical error happens to a patient with a DNR. If the error is reversible only with CPR or ventilation there is no consensus if resuscitation should take place or not.[37]

There are also ethical concerns around how patients reach the decision to make themselves a DNR. One study found that when questioned in more detail, many patients who were DNR actually would have wanted the excluded interventions depending on the scenario. Most would prefer life saving intubation in the scenario of angioedema which typically resolves in days. One fifth of the DNR patients would want resuscitation for cardiac arrest but to have care withdrawn after a week. It is possible that providers are having a "leading conversation" with patients or mistakenly leaving crucial information out when discussing DNR.[38] One study reported that physicians repeatedly give high intensity care to patients while deciding they themselves would be DNR under similar circumstances.[39]

There is also the ethical issue of discontinuation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in DNR patients in cases of medical futility. A large survey of Electrophysiology practitioners, the heart specialists who implant pacemakers and ICD's noted that the practitioners felt that deactivating an ICD was not ethically distinct from withholding CPR thus consistent with DNR. Most felt that deactivating a pacemaker was a separate issue and could not be broadly ethically endorsed. Pacemakers were felt to be unique devices, or ethically taking a role of "keeping a patient alive" like dialysis.[40]

Usage by country

DNR documents are widespread in some countries and unavailable in others. In countries where a DNR is unavailable the decision to end resuscitation is made solely by physicians.

Middle East

DNRs are not recognized by Jordan. Physicians attempt to resuscitate all patients regardless of individual or familial wishes.[41] The UAE have laws forcing healthcare staff to resuscitate a patient even if the patient has a DNR or does not wish to live. There are penalties for breaching the laws.[42] In Saudi Arabia patients cannot legally sign a DNR, but DNR accepted by order of primary physician in case of terminally ill patients. In Israel, it is possible to sign a DNR form as long as the patient is dying and aware of their actions.[citation needed]

United Kingdom

England and Wales

In England and Wales, CPR is presumed in the event of a cardiac arrest unless a do not resuscitate order is in place. If they have capacity as defined under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 the patient may decline resuscitation, however any discussion is not in reference to consent to resuscitation and instead should be an explanation.[43] Patients may also specify their wishes and/or devolve their decision-making to a proxy using an advance directive, which are commonly referred to as 'Living Wills'. Patients and relatives cannot demand treatment (including CPR) which the doctor believes is futile and in this situation, it is their doctor's duty to act in their 'best interest', whether that means continuing or discontinuing treatment, using their clinical judgment. If they lack capacity relatives will often be asked for their opinion out of respect.

Scotland

In Scotland, the terminology used is "Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation" or "DNACPR". There is a single policy used across all of NHS Scotland. The legal standing is similar to that in England and Wales, in that CPR is viewed as a treatment and, although there is a general presumption that CPR will be performed in the case of cardiac arrest, this is not the case if it is viewed by the treating clinician to be futile. Patients and families cannot demand CPR to be performed if it is felt to be futile (as with any medical treatment) and a DNACPR can be issued despite disagreement, although it is good practice to involve all parties in the discussion.[44]

United States

In the United States the documentation is especially complicated in that each state accepts different forms, and advance directives and living wills may not be accepted by EMS as legally valid forms. If a patient has a living will that specifies the patient requests of DNR but does not have a properly filled out state-sponsored form that is co-signed by a physician, EMS may attempt resuscitation.

The DNR decision by patients was first litigated in 1976 in In re Quinlan. The New Jersey Supreme Court upheld the right of Karen Ann Quinlan's parents to order her removal from artificial ventilation. In 1991 Congress passed into law the Patient Self-Determination Act that mandated hospitals honor an individual's decision in their healthcare.[45] Forty-nine states currently permit the next of kin to make medical decisions of incapacitated relatives, the exception being Missouri. Missouri has a Living Will Statute that requires two witnesses to any signed advance directive that results in a DNR/DNI code status in the hospital.

In the United States, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) will not be performed if a valid written "DNR" order is present. Many states do not recognize living wills or health care proxies in the prehospital setting and prehospital personnel in those areas may be required to initiate resuscitation measures unless a specific state-sponsored form is properly filled out and cosigned by a physician.[46][47]

Canada

Do not resuscitate orders are similar to those used in the United States. In 1995, the Canadian Medical Association, Canadian Hospital Association, Canadian Nursing Association, and Catholic Health Association of Canada worked with Canadian Bar Association clarify and create a Joint Statement on Resuscitative Interventions guideline for use to determine when and how DNR orders are assigned.[48] DNR orders must be discussed by doctors with the patient or patient agents or patient's significant others. Unilateral DNR by medical professionals can only be used if the patient is in a vegetative state.[48]

Australia

In Australia, Do Not Resuscitate orders are covered by legislation on a state-by-state basis.

In Victoria, a Refusal of Medical Treatment certificate is a legal means to refuse medical treatments of current medical conditions. It does not apply to palliative care (reasonable pain relief; food and drink). An Advanced Care Directive legally defines the medical treatments that a person may choose to receive (or not to receive) in various defined circumstances. It can be used to refuse resuscitation, so as avoid needless suffering.[49]

In NSW, a Resuscitation Plan is a medically authorised order to use or withhold resuscitation measures, and which documents other aspects of treatment relevant at end of life. Such plans are only valid for patients of a doctor who is a NSW Health staff member. The plan allows for the refusal of any and all life-sustaining treatments, the advance refusal for a time of future incapacity, and the decision to move to purely palliative care.[50]

Italy

DNRs are not recognized by Italy. Physicians must attempt to resuscitate all patients regardless of individual or familial wishes. Italian laws force healthcare staff to resuscitate a patient even if the patient has a DNR or does not wish to live. There are jail penalties (from 6 to 15 years) for healthcare staff breaching this law, e.g. "omicidio del consenziente".[51][better source needed] Therefore in Italy a signed DNR has no legal value.

See also

References

- ^ Weil, Max Harry; Gullo, Antonino; Ristagno, Giuseppe; Santonocito, Cristina (2013-02-01). "Do-not-resuscitate order: a view throughout the world". Journal of Critical Care. 28 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.07.005. ISSN 1557-8615. PMID 22981534.

- ^ Alternative to "DNR" Designation: "Allow Natural Death" - Making Sense in the Health Care Industry.

- ^ Pollak, Andrew. Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2017, isbn 978-1-284-10690-9, Page 540.

- ^ Vincent JL, Van Vooren JP (Dec 2002). "[NTBR (Not to Be Resuscitated) in 10 questions]". Rev Med Brux. 23 (6): 497–9. PMID 12584945.

- ^ Hooyer, C.; Schonwetter, R. S.; Van, C. Engen; Bezemer, P. D.; Duursma, S. A.; Dautzenberg, P. L. (1993-08-01). "Resuscitation decisions on a Dutch geriatric ward". The Quarterly journal of medicine. 86 (8): 535–542. ISSN 0033-5622. PMID 8210310.

- ^ van Mil, Annette H.M.; van Klink, Rik C.J.; Huntjens, Christine; Westendorp, Rudi G.J.; Stiggelbout, Anne M.; Meinders, A.Edo; Lagaay, A. Margot (2000-10-01). "Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Preferences in Dutch Community-dwelling and Hospitalized Elderly People: An Interaction between Gender and Quality of Life". Medical Decision Making. 20 (4): 423–429. doi:10.1177/0272989X0002000406. ISSN 0272-989X.

- ^ "Emergency Cardiovascular Care 2020 Impact Goals". web.archive.org, American Heart Association. 2017-10-08. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ "About CPR & ECC". cpr.heart.org. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ a b Benjamin Emelia J.; Virani Salim S.; Callaway Clifton W.; Chamberlain Alanna M.; Chang Alexander R.; Cheng Susan; Chiuve Stephanie E.; Cushman Mary; Delling Francesca N. (2018-03-20). "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 137 (12): e67–e492. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558.

- ^ Girotra, Saket; Vaughan-Sarrazin, Mary; Jones, Philip G.; Graham, Garth; Zhou, Yunshu; Bradley, Steven M.; Chan, Paul S.; Joseph, Lee (2017-09-01). "Temporal Changes in the Racial Gap in Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest". JAMA Cardiology. 2 (9): 976–984. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2403. ISSN 2380-6583.

- ^ "National Reports by Year « MyCares". mycares.net. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Merchant, Raina M.; Berg, Robert A.; Yang, Lin; Becker, Lance B.; Groeneveld, Peter W.; Chan, Paul S.; Investigators, for the American Heart Association's Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation (2014-01-31). "Hospital Variation in Survival After In‐hospital Cardiac Arrest". Journal of the American Heart Association. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Ehlenbach, William J.; Barnato, Amber E.; Curtis, J. Randall; Kreuter, William; Koepsell, Thomas D.; Deyo, Richard A.; Stapleton, Renee D. (2009-07-02). "Epidemiologic Study of In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in the Elderly". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (1): 22–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810245. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 2917337. PMID 19571280.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. (July 2009). "Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (1): 22–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810245. PMC 2917337. PMID 19571280.

- ^ Nolan, J.P.; Morley, PT; Vanden Hoek, TL; Hickey, RW; Kloeck, WG; Billi, J; Böttiger, BW; Morley, PT; Nolan, JP; Okada, K; Reyes, C; Shuster, M; Steen, PA; Weil, MH; Wenzel, V; Hickey, RW; Carli, P; Vanden Hoek, TL; Atkins, D; International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (2003). "Therapeutic Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest: An Advisory Statement by the Advanced Life Support Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation". Circulation. 108 (1): 118–21. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000079019.02601.90. PMID 12847056.

- ^ "Part 8: Post-Cardiac Arrest Care – ECC Guidelines". Resuscitation Science, section 11. 2015.

- ^ a b Orioles, Alberto; Morrison, Wynne E.; Rossano, Joseph W.; Shore, Paul M.; Hasz, Richard D.; Martiner, Amy C.; Berg, Robert A.; Nadkarni, Vinay M. (2013-12-01). "An under-recognized benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation: organ transplantation". Critical Care Medicine. 41 (12): 2794–2799. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829a7202. ISSN 1530-0293. PMID 23949474.

- ^ Sandroni, Claudio; D’Arrigo, Sonia; Callaway, Clifton W.; Cariou, Alain; Dragancea, Irina; Taccone, Fabio Silvio; Antonelli, Massimo (2016). "The rate of brain death and organ donation in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Intensive Care Medicine. 42 (11): 1661–1671. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4549-3. ISSN 0342-4642. PMC 5069310. PMID 27699457.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Girotra, S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Li Y, Krumholz HM, Chan PS. (2012). "Supplementary Appendix to "Trends in survival after inhospital cardiac arrest"" (PDF). NEJM: 17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hirsch, K. G.; Albers, G. W.; Mlynash, M.; Eyngorn, I.; Tong, J. T. (2016-12-01). "Functional Neurologic Outcomes Change Over the First Six Months after Cardiac Arrest, Functional Neurologic Outcomes Change Over the First 6 Months After Cardiac Arrest". Critical care medicine, Critical care medicine. 44, 44 (12, 12): e1202, e1202–e1207. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001963. ISSN 0090-3493. PMID 27495816.

- ^ "CPR - you CAN do it!". depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ a b Boland, Lori L.; Satterlee, Paul A.; Hokanson, Jonathan S.; Strauss, Craig E.; Yost, Dana (January–March 2015). "Chest Compression Injuries Detected via Routine Post-arrest Care in Patients Who Survive to Admission after Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest". Prehospital emergency care: official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors. 19 (1): 23–30. doi:10.3109/10903127.2014.936636. ISSN 1545-0066. PMID 25076024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Oschatz, E.; Wunderbaldinger, P.; Sterz, F.; Holzer, M.; Kofler, J.; Slatin, H.; Janata, K.; Eisenburger, P.; Bankier, A. A. (2001-07-01). "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed by bystanders does not increase adverse effects as assessed by chest radiography". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 93 (1): 128–133. ISSN 0003-2999. PMID 11429353.

- ^ a b Hoke, Robert, and Douglas Chamberlain (2004). "Skeletal chest injuries secondary to cardiopulmonary resuscitation" (PDF). Resuscitation. 63: 327–338.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "CPR Review - Keeping It Real". HEARTSAVER (BLS Training Site) CPR/AED & First Aid (Bellevue, NE). Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ "CPR Breaking Bones". EMTLIFE. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Coleman, Diane (2013-07-23). "Full Written Public Comment: Disability Related Concerns About POLST". Not Dead Yet. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Jesus, John E.; Allen, Matthew B.; Michael, Glen E.; Donnino, Michael W.; Grossman, Shamai A.; Hale, Caleb P.; Breu, Anthony C.; Bracey, Alexander; O'Connor, Jennifer L. (2013-07-01). "Preferences for resuscitation and intubation among patients with do-not-resuscitate/do-not-intubate orders". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88 (7): 658–665. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.04.010. ISSN 1942-5546. PMID 23809316.

- ^ a b Fendler, Timothy; Spertus, John A.; Kennedy, Kevin; Chen, Lena M.; Perman, Sarah M.; Chan, Paul S. (2017-11-01). "Association Between Hospital Rates of Early Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Favorable Neurological Survival Among Survivors of In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest". American heart journal. 193: 108–116. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2017.05.017. ISSN 0002-8703. PMC 5747564. PMID 29129249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Horwitz, Leora I. (2016-01-01). "Implications of Including Do-Not-Resuscitate Status in Hospital Mortality Measures". JAMA Internal Medicine. 176 (1): 105–106. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6845. ISSN 2168-6106.

- ^ Smith, Cardinale B.; Bunch O'Neill, Lynn (2008-10-01). "Do not resuscitate does not mean do not treat: how palliative care and other modalities can help facilitate communication about goals of care in advanced illness". The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York. 75 (5): 460–465. doi:10.1002/msj.20076. ISSN 1931-7581. PMID 18828169.

- ^ "Part 3: Ethical Issues – ECC Guidelines, Timing of Prognostication in Post–Cardiac Arrest Adults - Updated". Resuscitation, item 7.1, "Prognostication".

- ^ Richardson, Derek K.; Zive, Dana; Daya, Mohamud; Newgard, Craig D. (2013-04-01). "The impact of early do not resuscitate (DNR) orders on patient care and outcomes following resuscitation from out of hospital cardiac arrest". Resuscitation. 84 (4): 483–487. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.327. ISSN 1873-1570. PMID 22940596.

- ^ Dugan D, Riseman J. Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders in an Operating Room Setting #292. Journal of Palliative Medicine [serial online]. July 2015;18(7):638-639.

- ^ Garrido M, Harrington S, Prigerson H. End-of-life treatment preferences: A key to reducing ethnic/racial disparities in advance care planning?. Cancer (0008543X) [serial online]. December 15, 2014;120(24):3981-3986.

- ^ Humble M. Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Suicide Attempts. National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly [serial online]. Winter2014 2014;14(4):661-671.

- ^ Hébert P, Selby D. Should a reversible, but lethal, incident not be treated when a patient has a do-not-resuscitate order?. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal [serial online]. April 15, 2014;186(7):528-530.

- ^ Capone R. PROBLEMS WITH DNR AND DNI ORDERS. (Cover story). Ethics & Medics [serial online]. March 2014;39(3):1-3.

- ^ Physicians provide high-intensity end-of-life care for patients, but "no code" for themselves. Medical Ethics Advisor Volume: 30 Issue 10 (2014) ISSN 0886-0653

- ^ Daeschler M, Verdino RJ, Caplan AL, Kirkpatrick JN (2015). "Defibrillator Deactivation against a Patient's Wishes: Perspectives of Electrophysiology Practitioners". Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 38 (8): 917–924. doi:10.1111/pace.12614.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mideast med-school camp: divided by conflict, united by profession". The Globe and Mail. August 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

In hospitals in Jordan and Palestine, neither families nor social workers are allowed in the operating room to observe resuscitation, says Mohamad Yousef, a sixth-year medical student from Jordan. There are also no DNRs. "If it was within the law, I would always work to save a patient, even if they didn't want me to," he says.

- ^ "Nurses deny knowledge of 'do not resuscitate' order in patient's death". thenational.ae. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A joint statement from the British Medical Association, the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Royal College of Nursing" (PDF). Resus.org.uk. Resuscitation Council (UK). Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Scottish Government (May 2010). "Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR): Integrated Adult Policy" (PDF). NHS Scotland.

- ^ Eckberg, Evelyn (April 1998). "The continuing ethical dilemma of the do-not-resuscitate order". AORN Journal. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

The right to refuse or terminate medical treatment began evolving in 1976 with the case of Karen Ann Quinlan v New Jersey (70NJ10, 355 A2d, 647 [NJ 1976]). This spawned subsequent cases leading to the use of the DNR order.(4) In 1991, the Patient Self-Determination Act mandated hospitals ensure that a patient's right to make personal health care decisions is upheld. According to the act, a patient has the right to refuse treatment, as well as the right to refuse resuscitative measures.(5) This right usually is accomplished by the use of the DNR order.

- ^ "DO NOT RESUSCITATE – ADVANCE DIRECTIVES FOR EMS Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". State of California Emergency Medical Services Authority. 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-08-23. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

# What if the EMT cannot find the DNR form or evidence of a MedicAlert medallion? Will they withhold resuscitative measures if my family asks them to? No. EMS personnel are taught to proceed with CPR when needed, unless they are absolutely certain that a qualified DNR advance directive exists for that patient. If, after spending a reasonable (very short) amount of time looking for the form or medallion, they do not see it, they will proceed with lifesaving measures.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Frequently Asked Questions re: DNR's". New York State Department of Health. 1999-12-30. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

May EMS providers accept living wills or health care proxies? A living will or health care proxy is NOT valid in the prehospital setting

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-15. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Respect for the right to choose - Resources". Dying with dignity, Victoria. 2017. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- ^ "Using resuscitation plans in end of life decisions" (PDF). NSW government health department. 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- ^ it:Omicidio del consenziente (ordinamento penale italiano)

External links

- Do Not Resuscitate Orders Published by the U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Decisions Relating to Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Published by the Resuscitation Council (UK)