The 120 Days of Sodom

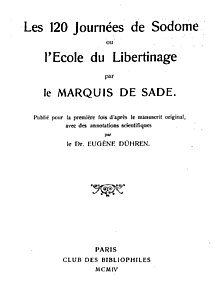

Title page of Les 120 Journées de Sodome, first edition, 1904 | |

| Editor | Iwan Bloch |

|---|---|

| Author | Marquis de Sade |

| Translator | Austryn Wainhouse |

| Language | French |

| Subject | Sadism |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | Club des Bibliophiles (Paris) Olympia Press |

Publication date | 1904 |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1954 |

| Media type | Print (Manuscript) |

| OCLC | 942708954 |

The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinage[a] (French: Les 120 Journées de Sodome ou l'école du libertinage) is an unfinished novel by the French writer and nobleman Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade, written in 1785 and published in 1904 after its manuscript was rediscovered. It describes the activities of four wealthy libertine Frenchmen who spend four months seeking the ultimate sexual gratification through orgies, sealing themselves in an inaccessible castle in the heart of the Black Forest with 12 accomplices, 20 designated victims and 10 servants. Four aging prostitutes relate stories of their most memorable clients whose sexual practices involved 600 "passions" including coprophilia, necrophilia, bestiality, incest, rape, and child sexual abuse. The stories inspire the libertines to engage in acts of increasing violence leading to the torture and murder of their victims, most of whom are adolescents and young women.

The novel only survives in draft form. Its introduction and first part were written according to Sade's detailed plan, but the subsequent three parts are mostly in the form of notes. Sade wrote it in secrecy while imprisoned in the Bastille. When the fortress was stormed by revolutionaries on 14 July 1789, Sade believed the manuscript had been lost. However, it had been found and preserved without his knowledge and was eventually published in a restricted edition in 1904 for its scientific interest to sexologists. The novel was banned as pornographic in France and English-speaking countries before becoming more widely available in commercial editions in the 1960s. It was published in the prestigious French Pléiade edition in 1990 and a new English translation was published as a Penguin Classic in 2016.

The novel attracted increasing critical interest after World War II. In 1957, Georges Bataille said it "towers above all other books in that it represents man's fundamental desire for freedom that he is obliged to contain and keep quiet".[1] Critical opinion, however, remains divided. Neil Schaeffer calls it "one of the most radical, one of the most important novels ever written",[2] whereas for Laurence Louis Bongie it is "an unending mire of permuted depravities".[3]

Text

[edit]Existing texts derive from an incomplete manuscript discovered after the storming of the Bastille in 1789. The novel consists of an introduction and four parts along with notes, supplements and addenda. Sade completed the introduction and first part in draft form. Parts Two to Four mainly consist of detailed notes.[4] Sade did not revise and correct the draft he had completed and therefore there are some errors and inconsistencies.[5]

Plot

[edit]

The 120 Days of Sodom is set near the end of the reign of Louis XIV.[6] Four wealthy libertines—the Duc de Blangis (representing the nobility), the Bishop of X*** (representing the clergy), the Président de Curval (representing the legal system), and Durcet (representing high finance)[7]—lock themselves in an isolated castle, the Château de Silling, atop a mountain in the Black Forest, along with a number of accomplices and victims. Their main accomplices are four middle-aged women, who have spent their lives in debauchery and will recount stories of libertinage, torture, and murder for the pleasure and instruction of the male libertines, who will then seek to emulate these crimes on selected victims. Eight male accomplices, called "fuckers", have been recruited for their large penises. The principal victims will be drawn from the libertines' four daughters, three of whom have been given in marriage to libertines other than their fathers. The other victims will be drawn from a harem of girls and boys, aged from 12 to 15. The libertines have also engaged other servants, including governesses, cooks, and scullery maids.[8]

The orgy takes place from 1 November to 28 February and is organised according to rules and a strict timetable, to which each of the victims must adhere on pain of corporal punishment or death. Sex sessions are scheduled before and after a session of storytelling each evening. Each storyteller is on duty for a month, and each evening she recounts a story from her life that illustrates five "passions" (perversions of the laws of nature and religion). Over the four months, therefore, there will be 120 stories, illustrating 600 passions. These passions are in four categories of increasing complexity and savagery—simple, complex, criminal, and murderous.[9] The four libertines frequently interrupt these stories to indulge in the described passions with the victims and others. They also emulate the passions in orgies after the stories are told.

- Introduction. The background to the 120-day orgy is presented in detail, along with character portraits of the four libertines and their daughters. Blangis opines that there is no god and that he is but a machine following the instincts given to him by Nature. Classification of deeds as virtue and vice are merely social conventions, and the only universal good is personal pleasure. Given that vice gives him the most pleasure, he is obeying Nature's dictates by indulging his vices and passions.[10]

- Part One. November, the simple passions. These anecdotes are written in detail. They are "simple" in the sense of not including sexual intercourse. The stories include sexual abuse of children, urine-drinking, vomit-drinking, coprophilia, and necrophilia. Blangis opines that Nature teaches us to hate our mothers. He later adds that crime is in itself pleasurable and thus in accordance with Nature. Curval, however, opines that after one commits the two or three greatest crimes, the pleasure palls. He would love to destroy the sun or use that star to burn the world.[11]

- Part Two. December, the complex passions. These anecdotes, written in note form, involve acts such as men who vaginally rape children as young as three and indulge in incest and flagellation. There are tales of men who indulge in sacrilegious activities, such as having sex with prostitutes during Mass. The female children are raped vaginally during the evening orgies. Other elements of that month's stories, such as whipping, are enacted.[12]

- Part Three. January, the criminal passions. The notes outline tales of libertines who indulge in criminal activities, albeit stopping short of murder. They include men who sodomise girls as young as three, men who prostitute their daughters to others and watch the proceedings, and others who mutilate women by tearing off their fingers or burning them with red-hot pokers. During the month, the four libertines have anal sex with the sixteen male and female children, who, along with the other victims, are treated more brutally as time goes on, with regular beatings, whippings, and torture.[13]

- Part Four. February, the murderous passions. The final 150 anecdotes, mostly written in note form, involve murder. They include libertines who skin children alive, disembowel pregnant women, burn entire families alive, and kill newborn babies in front of their mothers. The final tale is the only one written in detail since the simple passions of November: it features the "hell libertine", who is manually stimulated by servants while watching 15 teenage girls being simultaneously tortured to death. During this month, the libertines kill three of their four daughters along with four of the female children, two of the male ones, and one "fucker". The torture, murder, and mutilation of one of the girls is described in detail.[14]

- March. Sade lists those who have been murdered during the 120 days. The libertines decide to spare 12 of the survivors and murder the rest. The ones spared are the four storytellers, four of the fuckers, the three cooks, and Julie. They draw up a schedule of executions, one to be carried out each day. Sade then presents a final tally: 10 were murdered in the course of the orgies, 20 were killed from 1 March, and 16 returned to Paris.[15]

Characters

[edit]Four male libertines:

- The Duc de Blangis is a 50-year-old aristocrat who acquired his wealth by poisoning his mother for her inheritance. He also murdered his sister and three wives. He is tall, strong, and has a large penis and a voracious sexual appetite. He has murdered women during sexual intercourse but is a coward.

- The Bishop of X*** is Blangis's 45-year-old brother. He acquired his wealth by murdering two youths in his care and stealing their inheritance. He shares his brother's vices but is scrawny and weak. His passion is active and passive sodomy, and he also enjoys combining murder with sex. He is a misogynist who refuses to have vaginal intercourse.

- The Président de Curval is 60, lanky and "frightfully dirty about his body". He is a mysophiliac. He is a former judge who enjoyed sentencing the innocent to death. He once raped a young girl and forced her and her mother to watch the execution of the girl's father. He then murdered the two females.

- Durcet is a banker aged 53. He is short, chubby and pale, with a woman's figure. He murdered his mother, wife, and her niece to obtain a sizable inheritance. He is effeminate and his main passions are passive sodomy and fellatio. He has been in a sexual relationship with Blangis since their adolescence.

Their accomplices are:

- The storytellers. Four middle-aged female debauchées who will relate anecdotes of their depraved careers to inspire the four principal characters into similar acts of depravity.

- Madame Duclos is 48, witty, and still fairly attractive and well-kept.

- Madame Champville is 50, a lesbian, and likes having her 3-inch (8 cm) clitoris tickled. She is a vaginal virgin, but her rear is flabby and worn from use, so much so that she feels nothing there.

- Madame Martaine is 52 and prefers anal sex. A natural deformity prevents her from having vaginal intercourse.

- Madame Desgranges is 56, pale and emaciated, with dead eyes, whose anus is so enlarged she does not feel anything there. She is missing one nipple, three fingers, six teeth, and an eye. She is witty and the most depraved of the four; a murderer, rapist, and general criminal.

- Eight "fuckers" who are chosen chiefly because of their large penises. The four who are not identified by name are referred to only as "second-rank fuckers", and are killed in the final massacres during March.

- Hercule, 26

- Antinoüs, 30

- Bum-Cleaver (French: Brise-Cul, "Break-Arse")

- Invictus (French: Bande-au-ciel, "Erect-to-the-sky")

The victims are:

- The daughters of the four principal characters, whom they have been sexually abusing for years. All of them are murdered except Julie, who is spared after proving herself a libertine.

- Constance is 22. She is the daughter of Durcet and married to Blangis. She is tall, black-haired, attractive and completely ignorant of religion.

- Adelaide is 20. She is the daughter of Curval and married to Durcet. She is small, slightly built, blonde, romantic, virtuous and devoutly religious.

- Julie is 24. She is the daughter of Blangis and married to Curval. She is tall, plump and brown-haired. She has a stinking mouth and very poor anal and vaginal hygiene. She is corrupt.

- Aline is 18. She is the daughter of the Bishop and mistress of Blangis. She is tall and shapely, healthy, sober, clean, practically illiterate, and totally ignorant of religion.

- Eight boys and eight girls aged from 12 to 15, chosen for their beauty, virginity and high social status.

|

|

- Four middle-aged women, chosen for their ugliness to stand in contrast to the children, are brought along to serve as duennas.

- Marie, 58, who strangled all 14 of her children and one of whose buttocks is consumed by an abscess.

- Louison, 60, stunted, hunchbacked, blind in one eye and lame.

- Thérèse, 62, has no hair or teeth. Her anus is dirty and resembles the mouth of a volcano. All of her orifices stink.

- Fanchon, 69, is short and heavy, with large haemorrhoids. She is usually drunk, vomits constantly, and has faecal incontinence.

The libertines also recruit three female cooks (who are spared because of their skill) and three scullery maids.

Manuscript history

[edit]Sade wrote The 120 Days of Sodom over 37 days in 1785 while he was imprisoned in the Bastille. Being short of writing materials and fearing confiscation, he wrote it in tiny writing on a continuous roll of paper, made up of individual small pieces of paper smuggled into the prison and glued together. The result was a scroll 12 metres (39 ft) long and 12 centimetres (4.7 in) wide that Sade would hide by rolling it tightly and placing it inside his cell wall. As revolutionary tension grew in Paris, Sade incited a riot among the people gathered outside the Bastille when he shouted to them that the guards were murdering inmates; as a result, two days later on 4 July 1789, he was transferred to the asylum at Charenton, "naked as a worm" and unable to retrieve the novel in progress. Sade believed the work was destroyed when the Bastille was stormed and looted on 14 July 1789, at the beginning of the French Revolution. He was distraught over its loss and wrote that he "wept tears of blood" in his grief.[16]

However, the scroll was found and removed by a citizen named Arnoux de Saint-Maximin two days before the storming.[16] Historians know little about him or why he took the manuscript.[16] It was passed to the Villeneuve-Trans family and sold to a German collector around 1900.[17] It was first published in 1904[16] by the Berlin psychiatrist and sexologist Iwan Bloch (who used a pseudonym, "Dr. Eugen Dühren", to avoid controversy).[18][19] Viscount Charles de Noailles, whose wife Marie-Laure was a direct descendant of Sade, bought the manuscript in 1929.[20] It was inherited by their daughter Natalie, who kept it in a drawer on the family estate. She would occasionally bring it out and show it to guests, among them the writer Italo Calvino.[20] Natalie de Noailles later entrusted the manuscript to a friend, Jean Grouet. In 1982, Grouet betrayed her trust and smuggled the manuscript into Switzerland, where he sold it to Gérard Nordmann for $60,000.[20] An international legal wrangle ensued, with a French court ordering it to be returned to the Noailles family, only to be overruled in 1998 by a Swiss court that declared it had been bought by the collector in good faith.[18]

It was first put on display near Geneva in 2004. Gérard Lhéritier bought the scroll for his investment company for €7 million, and in 2014 put it on display at his Musée des Lettres et Manuscrits (Museum of Letters and Manuscripts) in Paris.[16][18][19] In 2015, Lhéritier was charged with fraud for allegedly running his company as a Ponzi scheme.[21] The manuscripts were seized by French authorities and were due to be returned to their investors before going to auction.[22] In December 2017, the French government recognised the original manuscript as a National Treasure giving the government time to raise funds to purchase it.[19][23][24] The government offered tax benefits to donors to help buy the manuscript for the National Library of France by sponsoring a sum of €4.55 million.[25] The French Government acquired the manuscript in July 2021.[26]

Reception

[edit]The first published versions of the novel, edited by Iwan Bloch (1904) and Maurice Heine (3 volumes, 1931–35), were limited editions intended as a compendium of sexual perversions for the use of sexologists.[27] Sade's critical reputation as a novelist and thinker, however, remained poor prior to World War II. In 1938, Samuel Beckett wrote, "not 1 in 100 will find literature in the pornography, or beneath the pornography, let alone one of the capital works of the eighteenth century, which it is for me."[28]

Sade received more critical attention after the war. Simone de Beauvoir in her essay "Must we burn Sade?" (published in 1951–52) argued that although Sade is a writer of the second rank and "unreadable", his value is making us rethink "the true nature of man's relationship to man".[29]

Georges Bataille, writing in 1957, stated:

In the solitude of prison, Sade was the first man to give a rational expression to those uncontrollable desires, on the basis of which consciousness has based the social structure and the very image of man... Indeed this book is the only one in which the mind of man is shown as it really is. The language of Les Cent Vingt Journées de Sodome is that of a universe which degrades gradually and systematically, which tortures and destroys the totality of the beings which it presents... Nobody, unless he is totally deaf to it, can finish Les Cent Vingt Journées de Sodome without feeling sick.[30]

Gilbert Lely considered the introduction to 120 Days of Sodom to be Sade's masterpiece, although he thought the rest of the novel was marred by Sade's emphasis on coprophilia.[31] Phillips,[32] and Wainhouse and Seaver, consider that Sade's later libertine novels have more literary merit and philosophical depth. Nevertheless, Wainhouse and Seaver conclude, "It is perhaps his masterpiece; at the very least, it is the cornerstone on which the massive edifice he constructed was founded."[31] In contrast, Melissa Katsoulis, writing in The Times of London, called the novel "a vile and universally offensive catalogue of depravity that goes far beyond kinky sex to the realms of paedophilia, torture and various other stomach-churning activities that we're all probably better off not knowing about."[33]

The novel was banned in France, the United States and the United Kingdom until the 1960s. In 1947, Jean-Jacques Pauvert published the first commercial French edition. He was prosecuted for obscenity in the 1950s but continued to publish.[34][35] In 1954, Olympia Press in Paris published an English edition translated by Austryn Wainhouse which was not sold openly in English-speaking countries.[35][36] The first commercial English edition was published in the United States by Grove Press in 1966.[35] In 1990 the novel was published in the prestigious French Pléiade edition, which Phillips calls a mark of "classic status".[34] In 2016, a contemporary English translation of the novel was published as a Penguin Classic.[37]

Themes and analysis

[edit]Academic John Phillips classifies The 120 Days of Sodom as a libertine novel. According to Phillips, Sade's intention was avowedly pornographic but he also intended the novel as social satire, a parody of the encyclopaedia and the scientific method, a didactic text expounding a theory of libertinage, and a fantasy of total power and sexual licence.[38] The novel displays typical Sadeian themes including an obsession with categorisation, order and numbers; an alternating presentation of dissertations and orgies; and a desire to catalogue all sexual practices.[27]

Phillips links the novel's emphasis on order, categorisation, numbers and coprophilia with the Freudian anal phase of human sexuality.[39] He also suggests that the novel's theme of mother hatred can be interpreted in Freudian terms as an unconscious erotic desire for the mother, with the château Silling as a womb symbol.[40]

Sade biographer Neil Schaeffer sees the main theme in the novel as rebellion against God, authority and sexual gender. Against these, Sade posits hedonism and an amoral, materialist view of nature.[41] Biographer Francine du Plessix Gray sees the novel as a dystopia, calling it "the crudest, most repellent fictional dystopia ever limned".[42]

Film adaptations

[edit]The final scene of Luis Buñuel's film L'Age d'Or (1930) shows the Duc de Blangis emerging from the château de Seligny. Buñuel had read the 120 Days and had been deeply impressed by its anti-clericalism and focus on sexuality.[43]

In 1975, Pier Paolo Pasolini made Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma). The setting is transposed from 18th-century France to the last days of Benito Mussolini's regime in the Republic of Salò. Salò is commonly listed among the most controversial films ever made.[44]

See also

[edit]- Philosophy in the Bedroom, Justine, and Juliette, other works by Sade

- Sadism

Notes

[edit]- ^ Alternatively The School of Licentiousness

Works cited

[edit]- Beckett, Samuel (2009). Fehsenfeld, Martha Dow; Overbeck, Lois More (eds.). The Letters of Samuel Beckett: 1921-1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86793-1.

- Bongie, Laurence Louis (1998). Sade: A Biographical Essay. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06420-4.

- Gray, Francine du Plessix (1998). At Home with the Marquis de Sade: a life. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80007-1.

- Lever, Maurice (1993). Marquis de Sade, a biography. Translated by Goldhammer, Arthur. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-246-13666-9.

- Phillips, John (2001). Sade: the Libertine Novels. London and Sterling, VA: Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-1598-4.

- Sade, Donatien Alphonse François (1987). Wainhouse, Austryn; Seaver, Richard (eds.). The 120 Days of Sodom and Other Writings. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3012-9.

- Schaeffer, Neal (2000). The Marquis de Sade: a Life. New York City: Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-67400-392-7.

References

[edit]- ^ Phillips 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Schaeffer 2000, p. 343.

- ^ Bongie 1998, p. 260.

- ^ Phillips 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Sade 1987, p. 570See editors' note 3.

- ^ Phillips 2001, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Phillips 2001, p. 36.

- ^ Sade 1987, pp. 191–260.

- ^ Sade 1987, pp. 241–55.

- ^ Sade 1987, p. 198–199.

- ^ Sade 1987, pp. 263–570.

- ^ Sade 1987, p. 573–595.

- ^ Sade 1987, p. 599–623.

- ^ Sade 1987, p. 627–672.

- ^ Sade 1987, p. 670–672.

- ^ a b c d e Perrottet, Tony (February 2015). "Who Was the Marquis de Sade?". Smithsonian Magazine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Phillips 2001, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Willsher, Kim (3 April 2014). "Original Marquis de Sade scroll returns to Paris". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "The 120 Days of Sodom: France seeks help to buy 'most impure tale ever written'". The Guardian. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Sciolino, Elaine (22 January 2013). "It's a Sadistic Story, and France Wants It". The New York Times. New York City. p. C1. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Paris, Angelique Chrisafis (6 March 2015). "France's 'king of manuscripts' held over suspected pyramid scheme fraud". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Noce, Vincent (16 March 2017). "Bankrupt French company's huge stock of precious manuscripts to go on sale". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "De Sade's 120 Days of Sodom declared French national treasure". RFI. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ de Freytas-Tamura, Kimiko (19 December 2017). "Halting Auction, France Designates Marquis de Sade Manuscript a 'National Treasure'". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ "Avis d'appel au mécénat d'entreprise pour l'acquisition par l'Etat d'un trésor national dans le cadre de l'article 238 bis-0 A du code général des impôts - Légifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Flood, Alison (13 July 2021). "€4.55m Marquis de Sade manuscript acquired for French nation". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Phillips 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Beckett 2009, p. 604.

- ^ Bongie (1998), p. 295

- ^ Bataille, Georges (2012). Literature and Evil. Translated by Hamilton, Alastair. Penguin Modern Classics. ISBN 9780141965970.

- ^ a b Sade 1987, p. 187.

- ^ Phillips 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Katsoulis, Melissa (23 February 2023). "The Curse of the Marquis de Sade". The Times. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ a b Phillips 2001, p. 25.

- ^ a b c McMorran, Will (22 December 2016). "'The 120 Days of Sodom' – counterculture classic or porn war pariah?". The Conversation. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Beckett 2009, p. 611note 3

- ^ "The 120 Days of Sodom: France seeks help to buy 'most impure tale ever written'". The Guardian. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Phillips 2001, pp. 41–42, 54–57.

- ^ Phillips 2001, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Phillips 2001, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Schaeffer 2000, p. 365.

- ^ Gray 1998, p. 265.

- ^ Gibson, Ian (1997). The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí. London: Faber and Faber. p. 235. ISBN 0-571-16751-9.

- ^ Saunders, Tristram Fane (7 July 2016). "Box-office gross: 12 movies that made audiences sick, from The Exorcist to The House that Jack Built". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

Bibliography

[edit]- Sade, Marquis de (1954). The 120 Days of Sodom; or, The Romance of the School for Libertinage. Translated by Casavini, Pieralessandro [pseud. of Austryn Wainhouse]. Paris: Olympia Press.

- The 120 Days of Sodom and Other Writings, Grove Press, New York; Reissue edition 1987 [First published 1966] ISBN 978-0-8021-3012-9

- The 120 Days of Sodom Penguin Books, London 2016 ISBN 978-0141394343

External links

[edit]- McLemee, Scott. "Sade, Marquis de (1740-1814)". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007.

- Novels by the Marquis de Sade

- 1785 novels

- 1904 French novels

- French LGBTQ novels

- 18th century in LGBTQ history

- Novels about French prostitution

- Obscenity controversies in literature

- Unfinished novels

- Prison writings

- Novels about child sexual abuse

- Novels about ephebophilia

- Novels about serial killers

- Novels set in Germany

- Literature about pedophilia

- French novels adapted into films

- Fiction about incest

- Novels published posthumously

- Fiction about matricide

- Fiction about sororicide

- Fiction about filicide

- Censored books

- Works about torture

- Books critical of Christianity

- Novels set in castles

- Black Forest

- Rediscovered works