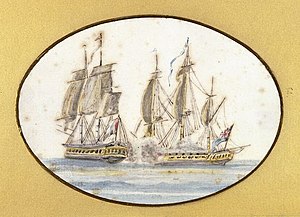

Action of 27 June 1798

| Action of 27 June 1798 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

Location of the engagement | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Captain Edward Foote | Captain G. F. J. Bourdé | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Frigate HMS Seahorse | Frigate Sensible | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 killed, 16 wounded | Heavy casualties, Sensible captured | ||||||

The action of 27 June 1798 was a minor naval engagement between British and French frigates in the Strait of Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea. The engagement formed part of a wider campaign, in which a major French convoy sailed from Toulon to Alexandria at the start of the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt. The French frigate Sensible had been detached from the convoy after the capture of Malta, under orders to carry wounded soldiers and looted treasure back to France while the main body continued to Egypt. The British frigate HMS Seahorse was one of a number of vessels detached from the main British Mediterranean Fleet in the Tagus River, sent to augment the fleet under Sir Horatio Nelson that was actively hunting the French convoy.

Lookouts on Seahorse spotted Sensible at 16:00 on 26 June and Captain Edward Foote immediately gave chase, the French frigate fleeing southwards. For 12 hours the pursuit continued until Foote was able to catch and defeat his opponent, inflicting heavy casualties on the weaker and overladen French frigate. Among the prisoners captured was General Louis Baraguey d'Hilliers who had been wounded in the storming of Malta, and among the treasure was an ornate seventeenth century cannon once owned by Louis XIV. The captured Sensible was initially fitted out as an active warship, but on arrival in Britain in 1799 the ship was downgraded to a transport. The action provided the British with the first conclusive evidence of the French intention to invade Egypt, but despite an extensive search for Nelson's fleet Foote was unable to relay the location of the French to his admiral before the Battle of the Nile on 1 August.

Background

On 19 May 1798, a French fleet departed Toulon for a top secret destination. The force consisted of 22 warships and 120 transports, to be joined by additional forces from Genoa, Corsica and Civitavecchia as it passed south through the Ligurian Sea.[1] The fleet's target was Egypt, a territory nominally controlled by the Ottoman Empire that French General Napoleon Bonaparte considered an ideal springboard for operations against British India.[2] Passing southwards without interference from the Royal Navy, which had been absent from the Mediterranean for over a year following the outbreak of war between Britain and Spain, Bonaparte's convoy passed Sicily on 7 June and two days later was at anchor off the harbour of Valletta on Malta. The island nation of Malta was under the command of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, a religious order that depended on France for much of its wealth and recruits. Bonaparte believed that capturing Malta was essential to controlling the Central Mediterranean, and when Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim refused the fleet entry to the harbour, Bonaparte responded with a large scale invasion. The knights put up no resistance, although fighting against native Maltese troops lasted for 24 hours until the central city of Mdina fell.[3] With this defeat the knights withdrew to their fortress at Valletta but were persuaded to surrender the following day with promises of pensions and estates in France.[4]

With Malta secure, Bonaparte seized the Maltese army and navy, adding them to his own forces. He garrisoned Valletta and among the wealth he appropriated from the island was the entire property of the Roman Catholic Church in the island.[5] Much of this was auctioned off, while other treasures were to be transported to France, along with dispatches carried by the wounded General Louis Baraguey d'Hilliers and other soldiers wounded during the invasion. On 19 June Bonaparte divided his forces, leaving 4,000 men to hold the island while the remainder of the convoy embarked on the second leg of the journey to Egypt.[6] One ship was detailed to return to France with the wounded, despatches and some of the treasure. For this purpose the 36-gun frigate Sensible under Captain G. F. J. Bourdé was selected, although much of the regular crew was removed and replaced with freed Maltese galley slaves.[7]

Although Bonaparte had not expected British interference in his operations against Egypt, the Royal Navy had responded to the reports of French mobilisation on the south coast by despatching a small squadron to the Ligurian Sea under Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson.[8] Arriving on 21 May, Nelson's squadron was struck by a severe storm and was forced to make hasty repairs off Sardinia. The storm had also dispersed the squadron's frigates, leaving Nelson with only three ships of the line. Although he was reinforced by another ten ships of the line and a fourth rate on 7 June, he still lacked any scouts and was thus severely hampered in his ability to search for information on French operations.[9] The detached frigates had been scattered across the Western Mediterranean, and were unable to locate either the British or the French fleets. Reinforcements sent by Vice-Admiral Earl St Vincent at the Tagus River suffered from the same problem, the frigates spreading out widely in their search but failing to discover either of the main British or French forces, which were rapidly sailing southeastwards towards Alexandria.[10]

Battle

One of the British reinforcements cruising in the Central Mediterranean in June was the frigate HMS Seahorse, commanded by Captain Edward Foote. Seahorse was officially rated as a 38-gun ship, but in reality carried 46 guns, including 14 32-pounder carronades, very heavy short-range cannon.[11] Foote had been despatched by Earl St. Vincent to join Nelson's squadron in his hunt for the French and carried on board a number of reinforcements for HMS Culloden, one of Nelson's ships commanded by Captain Thomas Troubridge.[12] On 26 June, Seahorse was passing along the southern Sicilian coast in search of information about the whereabouts of the British fleet when at 16:00 his lookout sighted a ship. Advancing rapidly, Foote recognised the stranger as a French frigate and prepared for battle. The frigate was Sensible, which was on a northeasterly course from Malta to Toulon when sighted. Bourdé, knowing that his ship was overladen, undermanned and carried only 36 guns, some of which were only 6-pounders, turned away and sailed south, hoping to outrun his opponent during the night.[11]

For 12 hours Sensible fled southwards, but Foote's pursuit was relentless and Bourdé found the distance between his frigate and Seahorse gradually disappearing.[12] At 04:00 on 27 July, with the island of Pantelleria 36 miles (58 km) to the northwest, Foote was able to pull Seahorse alongside his opponent and open a heavy fire from close range. At the first shots, many of the galley slaves deserted their positions and fled below decks, leaving the French ship dangerously exposed.[7] Within eight minutes Sensible was battered into submission, Bourdé's desperate attempt to board Seahorse easily avoided by Foote. The French frigate received 36 cannon shot in the hull and significant damage to the masts. Casualty estimates vary, but between 18 and 25 men were killed and 35 to 55 were wounded from a total of approximately 300.[11] Seahorse by contrast suffered only light damage, losing two men dead and 16, including First Lieutenant Wilmot, wounded.[12]

Foote removed much of the treasure and prisoners from Sensible before despatching the vessel under a prize crew to Earl St. Vincent in the Tagus. Among the goods seized from the frigate were copies of the French naval code books, as well as information about the destination of Bonaparte's invasion fleet.[13] Sailing immediately for Alexandria, Foote was joined soon afterwards by HMS Terpsichore under Captain William Hall Gage, who was also searching for Nelson. Together they reached Alexandria on 21 July, discovering that the French were already in the harbour although Nelson was nowhere to be seen.[14] Observing the French dispositions, Foote and Gage disguised their ships as a French frigate and its prize, Gage hoisting French colours over British to indicate that his ship had been captured and Foote displaying the secret French recognition codes. This appears to have convinced the French that the strangers were not enemy ships, and no move was made against them, Foote and Gage free to observe the French anchorage in Aboukir Bay before striking out along the African coast in search of Nelson.[14] The British admiral was at this time resupplying his ships at Syracuse on Sicily, and when he sailed on 25 July he passed eastwards to Morea where he learned of the French invasion of Egypt from the Turkish governor of Coron.[15] Striking directly southwards, Nelson arrived at Aboukir Bay on 1 August without ever encountering Foote or learning his intelligence. Seahorse eventually returned to Alexandria on 17 August to discover that Nelson had fought and won the Battle of the Nile nearly three weeks earlier.[16]

Aftermath

Earl St Vincent was suffering from an extreme shortage of frigates, and on the arrival of Sensible at the Tagus immediately ordered the frigate to be commissioned as HMS Sensible, stripping six men from each of his ships to man her and turning the frigate into an active warship in just 12 hours.[13] For a year Sensible remained with St. Vincent, until she was sent back to Britain in November 1799. On arrival the ship was downgraded from frontline service, but did spend several years commissioned as a military transport until wrecked off Ceylon on 3 March 1802.[17] Among the treasures removed from the ship was a decorated brass cannon captured from the Ottomans in the seventeenth century and presented to the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem by King Louis XIV of France, as well as a model of a galley made from gilt silver.[18] These were sold, along with the other cargo and ships fittings at Sheerness in November 1799, the prize money shares subsequently awarded to the crew of Seahorse.[19]

General d'Hilliers and the other prisoners were taken to Britain, but the officers were soon paroled. On their return to France, d'Hilliers and Bourdé were court martialled and initially condemned by the Minister of Marine Étienne Eustache Bruix. Bruix believed that the ship had been too easily surrendered and publicly released a strongly worded letter criticising their "talents and courage". This level of criticism, which British naval historian William James considers excessive, was eventually toned down and after a spirited defence by d'Hilliers both officers were honourably acquitted.[13] Foote was praised for his success, and Lieutenant Wilmot, who successfully carried the frigate to the Tagus, was promoted.[13] Foote later commanded Seahorse off Naples, and became embroiled in the controversy that surrounded the execution of the leaders of the Parthenopean Republic in 1799.[20]

References

- ^ James, p. 150

- ^ Adkins, p. 7

- ^ Cole, p. 8

- ^ Cole, p. 10

- ^ Gardiner, p. 21

- ^ Adkins, p. 13

- ^ a b Clowes, p. 510

- ^ Gardiner, p. 18

- ^ Clowes, p. 354

- ^ Keegan, p. 47

- ^ a b c James, p. 208

- ^ a b c "No. 15044". The London Gazette. 24 July 1798. p. 702.

- ^ a b c d James, p. 209

- ^ a b James, p. 160

- ^ Gardiner, p. 30

- ^ Clowes, p. 373

- ^ Grocott, p. 126

- ^ James, p. 210

- ^ "No. 15200". The London Gazette. 2 November 1799. p. 1132.

- ^ Laughton, J. K. "Foote, Sir Edward James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 22 October 2009. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

Bibliography

- Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11916-3.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Cole, Juan (2007). Napoleon's Egypt; Invading the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6431-1.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1996]. Nelson Against Napoleon. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-86176-026-4.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 2, 1797–1799. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-906-9.

- Keegan, John (2003). Intelligence in War: Knowledge of the Enemy from Napoleon to Al-Qaeda. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6650-8.