Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti

Aḥmad Bābā | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Born | 26 October 1556 Araouane, Mali |

| Died | 22 April 1627 (aged 70) Timbuktu, Mali |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Maliki[1] |

| Main interest(s) | Usul, Mantiq, Tafsir, Fiqh, Race, Slavery |

| Notable work(s) | Nayl al-ibtihāj bi-taṭrīz al-Dībāj (نيل الإبتهاج بتطريز الديباج) |

| Occupation | Teacher, Jurist, Scholar, Arabic Grammarian |

| Muslim leader | |

Influenced by | |

| Arabic name | |

| Personal (Ism) | Aḥmad Bābā أحمد بابا |

| Patronymic (Nasab) | ibn Aḥmad ibn al-Faqīh al-Ḥāj Aḥmad ibn ‘Umar ibn Muḥammad بن الفقيه الحاج أحمد بن عمر بن محمد |

| Teknonymic (Kunya) | Abu al-Abbas بن أحمد |

| Toponymic (Nisba) | al-Takrūrī al-Timbuktī التكروري التنبكتي |

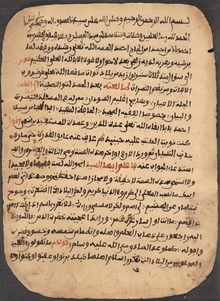

Aḥmad Bābā al-Timbuktī (Template:Lang-ar), full name Abū al-Abbās Aḥmad ibn Aḥmad ibn Aḥmad ibn Umar ibn Muhammad Aqit al-Takrūrī Al-Massufi al-Timbuktī (1556 – 1627 CE, 963 – 1036 H), was a Sanhaja Berber writer, scholar, and political provocateur in the area then known as the Western Sudan.[2] He was a prolific author and wrote more than 40 books.[3]

Life

Aḥmad Bābā was born on October 26, 1556 in Araouane to the Sanhaja Berber Aqit family.[4][5][6][7] He moved to Timbuktu at an early age where he studied with his father, Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥājj Aḥmad ibn ‘Umar ibn Muḥammad Aqīt,[8] and the scholar Mohammed Bagayogo (var. Baghayu'u); there are no other records of his activity until 1594, when he was deported to Morocco over accusations of sedition, after the Moroccan invasion of Songhai where he remained in Fez until the death of Ahmad al-Mansur. His successor, Zaydan An-Nasser, allowed all exiles to return to their country.[9] Aḥmad Bābā reached Timbuktu on April 22, 1608.[8]

Legacy

A fair amount of the work he was noted for was written while he was in Morocco, including the biography of Muhammad Abd al-Karim al-Maghili, a scholar and jurist responsible for much of the traditional religious law of the area. A biographical note was translated by M.A. Cherbonneau in 1855,[10] and became one of the principal texts for study of the legal history of the Western Sudan.[11] Ahmad Baba's surviving works remain the best sources for the study of al-Maghili and the generation that succeeded him.[12] Ahmad Baba was considered the Mujjadid (reviver of religion) of the century.

The only public library in Timbuktu, the Ahmed Baba Institute (which stores over 18,000 manuscripts) is named in his honor.[13][14]

In 1615 Ahmad discussed along with other Muslim scholars on the question of slavery, in order to protect Muslims from being enslaved. He is known to have provided one of the first ideas of ethnicity[clarification needed] within West Africa.[citation needed]

Stance on Race

Ahmad Baba made an effort to end racial slavery and criticised the association of Black Africans with slaves, particularly criticising some Muslims adopting the narrative of the Curse of Ham, found in the book of Genesis.[15]

However, Ahmad Baba was not an advocate for ending the slave trade generally. Rather, in writing the Mi'raj al Su'ud ila nayl hukm mujallab al-Sud, he sought only to reform the Trans-Saharan Slave Trade with the goal of preventing Muslims from enslaving other Muslims.

According to William Phillips, al-Timbukti essentially advocated religion-based slavery instead of racial-slavery, with Muslims of any ethnicity being immune from being enslaved.

Stance on Slavery

In regards to the enslavement of Africans in 1615, Ahmad Bābā discussed the legitimate reasons of how and why one could become a slave. The driving force, mainly being religious and ethnic, were that if one came from a country with a Muslim government, or identified with specific Muslim ethnic groups, then they could not be slaves. He claimed that if a person was an unbeliever or a kafara, then that is the sole factor for their enslavement, along with that being “the will of God.”

In the piece Ahmad Bābā and the Ethics of Slavery, he claims that his beliefs fueled the thought that those who identified as Muslim no longer had to be enslaved, but anyone that was an outsider (or nonbeliever) would then be enslaved by Muslims. These were not simply beliefs these were the rules that are given by God Most High, who knows best. Even in the case that the people of the country were believers but their belief was shallow then those people could still be enslaved with no questions asked. According to Ahmad Bābā, it was known that the people of Kumbe were shallow in their beliefs. He goes on to use the analogy that when one country is conquered and contains nonbelievers, then those persons could be enslaved as part of his stance on any other outsider or religion besides Islam.

This is a different kind of thinking in comparison to the works of William D. Phillips Jr., who wrote The Middle Ages Series: Slavery in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. In his piece, the main factor that distinguished a slave from an ordinary person would be their religious differences. This ties into Ahmad Bābā's ideas about enslavement involving everyone except those who practiced Islam. More specifically to his ideas on slavery, Phillips discussed how Christians enslaved Muslims, and Muslims enslaved Christians. However, Ahmad Bābā's hope was to end the enslaving of Muslims entirely and instead have other religious groups be enslaved, as they were considered to be unbelievers of the Muslim faith.

Another contradicting idea, discussed in the article Slavery in Africa by Suzanne Meirs and Igor Kopytoff, was that enslavement was based on people who are forced out of their homeland into a completely foreign area, tying into Ahmad's beliefs. Meirs and Kopytoff discuss the possibility of being accepted into a community through means of earning their freedom, being granted freedom by their owner, or being born into freedom. But in Ahmad Bābā's perspective, if one converted to Islam and were once an “unbeliever” before being enslaved, then that individual would still hold that title of being a slave. An unbeliever was classified as anyone who was Christian, Jewish, etc. however Ahmad Bābā states that there are no differences between unbelievers regardless of their different religious beliefs of Christianity, Persian, Jews, etc.

Notes

- ^ Hunwick 1964, pp. 568–570.

- ^ Cleaveland, Timothy (2015-01-01). "Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti and his Islamic critique of racial slavery in the Maghrib". The Journal of North African Studies. 20 (1): 42–64. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.983825. ISSN 1362-9387. S2CID 143245136.

- ^ "Timbuktu Hopes Ancient Texts Spark a Revival". The New York Times. August 7, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

The government created an institute named after Ahmed Baba, Timbuktu's greatest scholar, to collect, preserve and interpret the manuscripts. ...

- ^ Lévi-Provençal, Évariste (2012-04-24). "Aḥmad Bābā". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill.

- ^ Lévi-Provençal 1922, p. 251.

- ^ Fisher, Allan George Barnard; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1970). Slavery and Muslim Society in Africa: The Institution in Saharan and Sudanic Africa, and the Trans-Saharan Trade. C. Hurst. p. 30. ISBN 9780900966248.

- ^ Cleaveland, Timothy (2015). "Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti and his Islamic critique of racial slavery in the Maghrib". The Journal of North African Studies. 20 (1): 42–64. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.983825. ISSN 1362-9387. S2CID 143245136.

- ^ a b Hunwick 1964, p. 569

- ^ Lévi-Provençal 1922, pp. 251–253.

- ^ Cherbonneau, M.A. (1855), "Histoire de la littérature arabe au Soudan", Journal Asiatique (in French), 4: 391–407.

- ^ Batrān, 'Abd-Al-'Azīz 'Abd-Allah (1973), "A contribution to the biography of Shaikh Muḥammad Ibn 'Abd-Al-Karīm Ibn Muḥammad ('Umar-A 'Mar) Al-Maghīlī, Al-Tilimsānī", Journal of African History, 14 (3): 381–394, doi:10.1017/s0021853700012780, JSTOR 180537, S2CID 162619999.

- ^ Bivar, A. D. H.; Hiskett, M. (1962), "The Arabic Literature of Nigeria to 1804: A Provisional Account", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 25 (1/3): 104–148, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00056287, JSTOR 610779, S2CID 153514572.

- ^ Curtis Abraham, "Stars of the Sahara," New Scientist, 18 August 2007: 38

- ^ "Islamist rebels torch Timbuktu manuscript library: mayor". Reuters. January 28, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ Cleveland, Timothy (January 2015). "Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti and his Islamic critique of racial slavery in the Maghrib". The Journal of North African Studies. 20 (1): 42–64. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.983825. S2CID 143245136. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

References

- Hunwick, J.O. (1964), "A New Source for the Biography of Ahmad Baba al-Tinbukti (1556-1627)", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 27 (3): 568–593, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00118385, JSTOR 611391, S2CID 162780325

- Lévi-Provençal, Evariste (1922). Les historiens des Chorfa; essai sur la littérature historique et biographique au Maroc du XVIe au XXe siècle. Paris E. Larose.

- Hunqick J. and Harrak F. (2000). "Mi'raj al-su'ud: Ahmad Baba's Replies on Slavery". pp 30-33.

- Meirs S. and Kopytoff I. (1993). "Slavery in Africa". pp 264 –276.

- Phillips W.D. (2013). "The Middle Ages Series: Slavery in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia". pp 1–27.