Anna Heikel

Anna Heikel | |

|---|---|

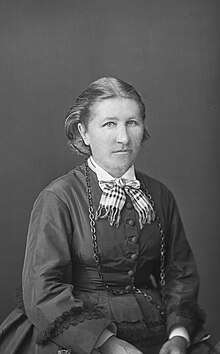

Anna Heikel, 20 August 1877 Credit: Daniel Nyblin | |

| Born | 2 February 1838 |

| Died | 3 April 1907 (aged 69) |

| Occupation | Educator |

| Known for | Education of the deaf, contributions to the Baptist church in Finland, founding an early Sunday school, temperance work |

| Movement | Baptist, temperance movement |

| Parents |

|

Anna Charlotta Heikel (2 February 1838 – 3 April 1907) was a Finland-Swedish teacher and director of the School for the Deaf in Jakobstad, Finland, from 1878 to 1898. She was a temperance activist as well as a pioneer of the Baptist movement in Finland and early Sunday school founder.[1]

Upbringing and education

Heikel was born in Turku, Finland, on 2 February 1838 to Lutheran priest and educator Henrik Heikel. She was one of 11 children, among them gymnastics teacher and educator, Viktor Heikel, and Felix Heikel, a banker and politician.[2][3] Ethnologist Yngvar Heikel was her nephew.

From 1848 to 1853, she attended the Svenska fruntimmersskolan i Åbo, a girls' school in Turku.[4]

At 22 years old, Anna Heikel did an internship with the "apostle to the Deaf", Carl Henrik Alopaeus, in Turku. Alopaeus was a bishop and headmaster of the school for the deaf in Turku, and also conducted research on teaching the deaf.[5][6] They would continue to work together for many years, also later traveling to the area of Lappmarken in the summer of 1866, where they instructed the deaf.[4] Heikel became the first female teacher for the deaf in Finland.[7] She worked voluntarily for many years without receiving pay.[6]

School for the Deaf

Credit: Jakob (?) Grönroos

After the family moved from Turku to Pedersöre in 1861, Heikel and her father founded a school for the deaf the same year on the rectory property at his expense; her sister also taught there. According to Dövas Församlingsblad, "Anna and her sister Selma were responsible for teaching in the beginning before a deaf teacher, Lorentz Eklund, was hired. Anna then also served as director of the school."[8] The school was visited by Alopaeus a year later, who noted a great need in the area. Around this time, Heikel and her brother Viktor also studied folk schools in Stockholm.[4] A separate building was built in 1863; the school's operations were also taken over by the state that year.[9] The school had over one hundred students in the early 1880s. Due to a lack of space, it was moved to nearby Jakobstad in 1887 and became a boarding school.[10] The school was eventually closed in 1932.[11]

Educational methods

Along with the school for the deaf in Porvoo (Swedish: Borgå), which operated from 1846 to 1991, it was one of two schools for the deaf for the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland.[12] At a time when oralism was common in deaf education, Heikel did not support its use but rather supported the use of sign language.[13] The school in Jakobstad (Finnish: Pietarsaari) took in students from the school in Porvoo who had not learned spoken Swedish. There they were educated in Finland-Swedish sign language and written Swedish.[14]

Contribution to the Baptist movement

Together with her family and others, Heikel played a central role in the beginnings of the Baptist movement in Finland. At the time, all religious gatherings outside of those of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland were forbidden by the Conventicle Act, "used to restrict the pietistic revival movements in Finland".[15]

In 1859, a number of members of the growing Baptist movement in Åland faced hearings in front of the Bishop's Chapter at the Turku Cathedral. Among the Lutheran clergy present was Henrik Heikel, who took an interest in the Baptists' beliefs and spoke to them to learn more, although he did not convert. After moving to Pedersöre in 1860, the Heikel family maintained a connection with the Baptists in Åland. After Henrik Heikel's death in 1867, both Anna and her brother Viktor were baptized in Stockholm by Anders Wiberg; Netta was also baptized.[16][17] After her return, she began to hold meetings and share material on Baptist teachings. Heikel and her circles were influenced by the teachings of Carl Olof Rosenius and the Nyevangelism (lit. 'New Evangelism') movement.[18]

The family received a visit from a Baptist pastor who had been at the hearing with Henrik Heikel ten years earlier; together they held meetings and the pastor's preaching led to more conversions.[19][20] Four members of the Heikel family, along with nine others, founded a Swedish-language Baptist church in Jakobstad in 1870.[16] At one point she was called to a hearing at the cathedral chapter regarding her conversion; there she was defended by Alopaeus, who, while not Baptist himself, supported her beliefs.[4] Her beliefs were also controversial in the community and forced her to leave teaching for a time.

Anna and Netta would eventually leave the Baptists and join the Fria missionsförbundet.[21]

Sunday school

In 1861, Heikel and her sister Sofia Antoinetta (Netta) founded one of the first free church Sunday schools in the country. Later, while in Stockholm in 1868, she also learned more about the Swedish Sunday school system. The Swedish Sunday school movement had begun to grow significantly in recent years in part due to the work of Mathilda Foy, Betty Ehrenborg, and Per Palmqvist, who in turn modeled them after Methodist George Scott's work in London.[21][22][23][24] She and Netta began to hold Sunday school classes at the school in 1868. They soon encouraged their friends, Miss Hellman and Miss Humble, to start a Sunday school in Vaasa.[4] She continued to teach Sunday school even after later leaving the Baptist church for the Fria missionsförbundet.[21]

Temperance movement

Swedish Baptist missionary and colonel Oscar Broady held temperance talks in Vaasa in the late 1870s.[25] The movement first spread to Anna and Netta's friends, the Hellmans, in Vaasa, and was soon taken up by the Heikel sisters. They formed the country's first teetotalism association in Jakobstad in 1877, attended by exclusively Baptists, including a number of children; the association caused so much controversy in the town that some students were expelled and the two were forced to leave their teaching jobs.[4][26]

Death and legacy

Heikel died 3 April 1907 in Jakobstad. A plaque dedicated to Heikel was unveiled there in 2014.[11]

See also

References

- ^ Otavan Iso tietosanakirja, osa 3, p. 511, s.v. Heikel, Henrik. Otava 1968. (in Finnish)

- ^ "HEIKEL, Viktor". Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "255-256 (Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 11. Harrisburg - Hypereides)". runeberg.org (in Swedish). 1909. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Jossfolk, Karl-Gustav (2001). Bildning för alla: en pedagogikhistorisk studie kring abnormskolornas tillkomst i Finland och deras pionjärer som medaktörer i bildningsprocessen 1846-1892 (PDF) (in Swedish). Svenska skolhistoriska föreningen i Finland, (Nord Print). Helsinki: Svenska skolhistoriska föreningen i Finland. pp. 181–185, 270–271. ISBN 952-91-3442-8. OCLC 58384770. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Carl Henrik Alopaeus". The Finnish Museum of the Deaf. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Anna Heikel" (PDF). Kuuromykkäin lehti (in Finnish). 2. March 1897. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2021.

- ^ Wecksell, Helmi. "Om Aurora Heikel född von Knorring (2 juni 1819-24 febr 1904 i Vichtis)" (PDF) (in Swedish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2021.

- ^ Ahlskog, Olof. "Dövstumskolan i Jakobstad/Pedersöre 150 år". Dövas församlingsblad (in Swedish). 34. Kyrkans central för det svenska arbetet/diakoni och samhällsansvar. ISSN 0359-0445. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021.

- ^ Londen, Monica (2004). COMMUNICATIONAL AND EDUCATIONAL CHOICES FOR MINORITIES WITHIN MINORITIES: The case of the Finland-Swedish Deaf. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.336.6046. ISBN 952-10-0813-X. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022.

- ^ Jossfolk, Karl-Gustav (2017). "Carl Oskar Malm, en döv visionär" (PDF). SFV-kalendern 2017 (in Swedish). 131. Svenska folkskolans vänner. eISSN 2243-0261. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Till minne av Dövstumskolan i Pedersöre-Jakobstad". YLE (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Andersson-Koski, Maria. Mitt eget språk – vår kultur: En kartläggning av situationen för det finlandssvenska teckenspråket och döva finlandssvenska teckenspråkiga i Finland 2014-2015 (PDF) (in Swedish). ISBN 978-952-93-5979-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2021.

- ^ Harjula, Minna. "Heikel, Anna (1838 - 1907)". Suomen kansallisbiografia (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Smakbitar från Livs-utbildningen". Livs (in Swedish). 14 December 2016. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Sinnemäki, Kaius; Portman, Anneli; Tilli, Jouni; Nelson, Robert H. (10 December 2019). On the Legacy of Lutheranism in Finland: Societal Perspectives. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. p. 229. ISBN 978-951-858-150-8. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b Wardin, Albert W. (2013). On the Edge: Baptists and Other Free Church Evangelicals in Tsarist Russia, 1855-1917. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 33. ISBN 9781620329627.

- ^ Wiberg, Anders (1864). "Mission in Sweden". Annual Report of the American Baptist Missionary Union. American Baptist Foreign Mission Society. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Susanna kom Anna in på livet". Missionstandaret (in Swedish). 4 (111). 2003. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007.

- ^ "Helsingfors baptistförsamling". Betelkyrkan (in Swedish). 7 March 2016. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Sundqvist, Alfons (January 1954). "Glimpses of the Baptist Work in Finland" (PDF). The Fraternal. 91. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Norström, Per (1 November 1930). "Söndagsskolans historia". Evangeliskt vittnesbörd (in Swedish). No. 21. p. 163, 166. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Hildebrand, Bengt. "A C Mathilda Foy". Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ McFarland, John Thomas; Winchester, Benjamin S. (1915). The encyclopedia of Sunday schools and religious education; giving a world-wide view of the history and progress of the Sunday school and the development of religious education. T. Nelson & sons. p. 1061.

About 1850, Mr. Per Palmqvist and Miss Betty Ehrenborg visited England and upon their return to Stockholm they organized Sunday schools according to the English form. From this small beginning Sunday-school work has grown in magnitude...

- ^ Bexell, Oloph. "Per Palmqvist". Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ Granqvist, Ture. "Nykarleby Nykterhetsförening 1886-1936". www.nykarlebyvyer.nu (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "Banbryterskor". Balder (in Swedish). 11 (6): 1–2. 15 March 1906. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

Further reading

- Backlund-Enges, Susanna: Anna Heikel: Dövstumslärarinna – andlig ledare – samhällspåverkare. 2001. Åbo Akademi.

External links

![]() Media related to Anna Heikel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Anna Heikel at Wikimedia Commons