Bojagi

| Bojagi | |

Silk patchwork Bojagi from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 보자기 |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | bojagi |

| McCune–Reischauer | pojagi |

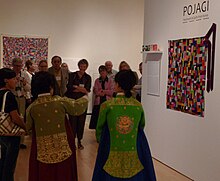

A bojagi (Korean: 보자기; MR: pojagi, sometimes shortened to 보; bo; po) is a traditional Korean wrapping cloth. Bojagi are typically square and can be made from a variety of materials, though silk or ramie are common. Embroidered bojagi are known as subo, while patchwork or scrap bojagi are known as jogak bo.

Bojagi have many uses, including as gift wrapping, in weddings, and in Buddhist rites. More recently, they have been recognized as a traditional art form, often featured in museums and inspiring modern reinterpretations.

History[edit]

Traditional Korean folk religions believed that keeping something wrapped protected good luck.[1] It is believed that the earliest use of the wrappings dates to the Three Kingdoms Period, but no examples survive from this period.[2]

The earliest surviving examples, from the early Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), were used in a Buddhist context, as tablecloths or coverings for sutras. The cloths particularly marked special events, such as weddings or betrothals, where the use of a new cloth was believed to convey "an individual's concern for that which was being wrapped, as well as respect for its recipient." For a royal wedding, up to 1,650 bojagi might be created.[2]

Everyday use of bojagi declined in the 1950s, and they were not treated by Koreans as art objects until the late 1960s.[2][3] Since the 1980s, many exhibitions have been organized in Korea and around the world to showcase the beauty and significance of bojagi made by Korean women.[4] In 1997, the "Korean Beauty" postage stamp series included four stamps featuring bojagi.[5]

Physical characteristics[edit]

Traditionally, the bojagi is a square, measuring from one pok in width (approximately 35 cm), for small items, to ten pok for larger objects such as bedding.[6] Materials included silk, cotton, ramie, and hemp. Colors ranged from red, purple, blue, green, yellow, and pink to dark blue, white, and black. Bojagi were sometimes embellished to be lined, unlined, padded, quilted, or decorated with painting, paper-thin gold sheets, embroidery, and patchwork.[4]

Royal bojagi (gung-bo)[edit]

Royal wrapping cloths were known as gung-bo.[6] Gung-bo were made from a single piece of cloth, and although left unsigned, gung-bo cloths were made by known artisans and painters of court offices, distinct from the min-bo pojagi made by anonymous, unknown artists.[4] Within the Joseon royal court the preferred fabric in bojagi construction was domestically produced pink-red to purple cloth.[7] These fabrics were often painted with designs, such as dragons.[2]

Unlike the used and re-used frugality of non-royal wrapping cloths, hundreds of new bojagi were commissioned on special occasions such as royal birthdays and New Year’s Day.[2] The names of women employed by the court to make bojagi for specific royal rituals, such as wedding ceremonies, are listed in official court records of the Ŭigwe (Royal Protocols). Several female needleworkers' names appear repeatedly in these records, pointing to the value of their high level of skill. In the eighteenth century, female needleworkers' wages appear to have been comparable to those of male artisans.[8]

Common bojagi (min-bo or jogak bo)[edit]

Min-bo or jogak bo (조각보) were "patchwork" bojagi made by commoners.[9] In contrast with the royal gung-bo, which were not patchwork,[2] these cloths were created from small segments ("jogak") of fabric from other sewing, such as those left over from cutting the curves in traditional hanbok clothing.[3]

Korean women, taught from an early age to be patient and frugal, would separate small scraps of cloth into different groups according to material, shape, colors, and weight. This process provided an opportunity for Joseon dynasty women to express their creative talents, with the actual sewing likely similar to sutra copying. Makers of this “patchwork” bojagi made no effort to hide their stitches and may have believed that blessings and good fortune (pok) accumulated with each added stitch and piece.[4] Both symmetrical 'regular' and random-seeming 'irregular' patterned cloths were sewn, with styles presumably selected by an individual woman's aesthetic tastes.[2]

As food coverings[edit]

Jogak bo are closely associated with food coverings. The mid-19th century to early 20th century examples that have survived until the present day often have a small loop of ribbon attached in the centre of the square, to aid in lifting the cover away from food. Table-sized bojagi often have straps attached to the corners, so they can be fastened to the table, to secure items in place, when the table is moved.[7]

Different bojagi were used for covering different foods and at different seasons. While lightweight cloths helped air to circulate during summer, to keep food warm in winter bojagi could be padded and lined as well.[7] To prevent the bojagi from being dirtied from food, the underside is often lined with oiled paper.[2][7]

For carrying items[edit]

Bojagi were used for transporting items, as well as covering, or keeping things together in storage. One such example is a 'knapsack' arrangement, where the cloth is wrapped and tied so that items can be securely transported upon ones' back.

Embroidered bojagi[edit]

Embroidered bojagi, also called subo (수보) (the prefix su means embroidery), was another form of decorated cloth. A common ornament was that of stylized trees, varying in style from 'naive',[9] to detailed depictions of flowers, fruits, birds, dragons, clouds and symbols of good luck.[10][11] These cloths are closely associated with joyous occasions such as betrothals and weddings,[2] used to wrap items such as gifts from the family of the bridegroom to the new bride, and the symbolic wooden wedding geese which is a metaphor of the groom's fidelity and protection.[12][2]

The embroidery was done with spun thread, on a cotton or silk ground. The subo fabric was then lined, and possibly padded.[2] Mothers of brides during the Joseon Dynasty frequently stitched dozens of bojagi for their daughters to take to their new homes. Because many survive in pristine condition, these bojagi did not have a practical function, but served as signs of affection and good wishes.[2]

Romantic connotations[edit]

Kirogi po, or wrapping cloths for a wedding goose, was another form of bojagi used to wrap a wooden goose presented by the bridegroom to the bride's family during traditional Korean wedding ceremonies, symbolizing the groom's fidelity. In addition to being lined and embroidered, the kirogi po were often decorated with strands of rainbow-colored threads representing rice stalks, a symbol of the family's wishes for abundance in married life. Trees, flowers, fruits, butterflies, and birds were commonly depicted to symbolize prosperity, honor, happiness, and joy.[4]

Modern references and exhibitions[edit]

The Museum of Korean Embroidery in Seoul has a collection of 1,500 pieces of bojagi, with a particular focus on jogak bo (quilt-like patchworks).[3] The museum was founded by husband-and-wife duo Dong-hwa Huh (허동화; 1926−2018) and Young-suk Park (박영숙; born 1932) with the aim of preserving Korean embroidery arts and educating the public on its artistic and historical significance. Huh and Park's bojagi collection garnered international attention, with sixty overseas exhibitions displayed in eleven countries.[13]

In April 2018, Huh and Park donated the majority of their collection to the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.[13]

The Seoul Museum of Craft Art is built on what was the Royal Craft Workshop of the Joseon Dynasty, where court women created textile products made for everyday use. The Museum made its grand opening in 2021 and is an open space where traditional and modern crafts come together.[13]

Museum collections outside of Korea, including in Kyoto,[14] London,[15] San Francisco,[16] and Los Angeles,[17] also contain bojagi.

The patchwork style of the jogak bo have inspired artists working in other media, such as clothing designers Lee Chunghie[15][18] and Karl Lagerfeld.[19] The facade of the flagship store of French jeweler Cartier in Cheongdam-dong is also reportedly inspired by the craft.[20] Japanese embroiderers have also worked in the style.[14]

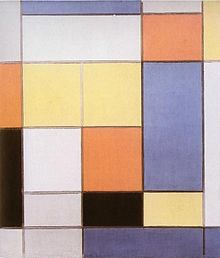

The patterns of jogak bo have been compared to the work of Paul Klee and Piet Mondrian.[2][3][9]

See also[edit]

- Hanbok: traditional Korean clothing

- Furoshiki: Japanese wrapping cloth

- Chinese patchwork

References[edit]

- ^ Korean Culture and Information Service Ministry of Culture (2010). Guide to Korean Culture. Hollym Corp. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-56591-287-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (2004-01-01). "A Celebration of Life: Patchwork and Embroidered Pagoji by Unknown Korean Women". Creative Women of Korea: The Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Centuries. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765611895.

- ^ a b c d "Beauty of 'jogakbo' rediscovered". The Korea Times. 2016-12-04. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ a b c d e Creative women of Korea : the fifteenth through the twentieth centuries. Young-Key Kim-Renaud. London [England]. 2015. ISBN 978-1-315-70537-8. OCLC 905917070.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "South Korea Stamps 1997". 2004-08-09. Archived from the original on 2004-08-09. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ a b Kim, Keumja Paik "Profusion of Colour: Korean Costumes and Wrapping Clothes of the Chosŏn Dynasty" in Julia M. White and Huh Dong-hwa [eds.] Wrappings of Happiness: A Traditional Korean Art Form (Honolulu Academy of Arts Publishing: 2003)

- ^ a b c d Huh Dong-hwa "History and Art in Traditional Wrapping Cloths" in Julia M. White and Huh Dong-hwa [eds.] Wrappings of Happiness: A Traditional Korean Art Form (Honolulu Academy of Arts Publishing: 2003) pp. 20–24

- ^ Gender, continuity, and the shaping of modernity in the arts of East Asia, 16th-20th centuries. Kristen L. Chiem, Lara C. W. Blanchard. Boston. 2017. ISBN 978-90-04-34895-0. OCLC 1000385969.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Gowman, Philip (2009-02-28). "Mudang and minhwa: It's a wrap". London Korean Links. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ Framed Royal Purple Wrapping Cloth with Peacocks Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine Korean Art and Antiques

- ^ "보자기" [Our Traditional Cloths] (in Korean). 2011-07-22. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ Lee, Patricia (2009). The Wrapping Scarf Revolution: The Earth-friendly Idea that Will Change the Way You Think about Your World. Leisure Arts. p. 18. ISBN 9781574861068.

- ^ a b c Gold needles : embroidery arts from Korea / Sooa Im McCormick, curator. Sooa Im McCormick, Jung-Wha Kim, William Griswold, Seung-Hae Yi, Byungmo Chung, Young Chae. Cleveland, OH. 2020. ISBN 978-1-935294-72-6. OCLC 1175646323.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "'Bojagi' culturally links Korea, Japan". The Korea Times. 2014-01-21. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ a b "Lee Chunghie". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ "Bojagi". Asian Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2019-05-04. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ "Bojagi: The Korean Wrapping Cloth". LACMA. 2 January 2014. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ "SDA Members In Print: Chunghie Lee Publishes 'Bojagi & Beyond'". Surface Design Association. 2011-09-26. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ^ "'Couture Korea' exhibit paints past, present, future of Korean fashion". The Daily Californian. 2017-11-06. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- ^ Garcia, Cathy Rose A. (28 September 2008). "Cartier Opens Flagship Store in Cheongdam". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

External links[edit]

Media related to Bojagi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bojagi at Wikimedia Commons- Cloth, Color and Beyond: Korea Society Bojagi Podcast Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- youngminlee.com Bojagi – Youngmin Lee's Korean Textile Works

- Bojagi at Asian Art Museum of San Francisco - includes video and several examples from the museum's collection