CEN 1789

CEN 1789 | |

|---|---|

|

CEN 1789:2020 is the European Union standard for ambulances and medical transportation vehicles. This European standard specifies requirements for the design, testing, performance and equipping of road ambulances used for the transport and care of patients. This standard is applicable to road ambulances capable of transporting at least one person on a stretcher.[1]

History

The current version of standard CEN 1789 was published by the Comité Européen de Normalisation (European Committee on Standardization) on October 1, 2020. This replaced an early version of the standard, published in 2007. European standards are generally annotated by the organization, standard number and year of publication (e.g. CEN 1789:2000 or CEN 1789/2007). Within member countries,[2] the annotation is likely to be adapted to include the local standards body, so that in Britain, the 'C' is dropped from the prefix, and replaced with 'BS', in Germany with 'DIN', and so on. Because of the likelihood of significant changes between versions, only the most current version of any standard should be used. The Comité Européen de Normalisation is an agency of the government of the European Union, with membership from the National Standards Body of each participating member country.

While CEN 1789:2020 represents the current European standard for the design of ambulances, it is by no means the only example of such a standard. Standards for ambulance design have existed in the United States since 1976, where the standard is known as KKK-1822-A.[3] This standard has been revised several times, and is currently in version 'F', known as KKK-1822-F. As with the European system, only the most current version of the standard should be used. One of the first known standards for ambulance design occurred in London, England, as the result of efforts by the Metropolitan Asylums Board, acting in response to the cholera outbreak of 1832. While horse-drawn, this provided the actual standard for many of the earliest civilian ambulances around the world. More contemporary versions of ambulance design standards also exist at a local level in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In each case, the country or jurisdiction develops such standards based upon its own needs, priorities, and realities, and this is also true of the European standard. In some cases, standards compliance may not be planned, and may occur as an incidental result of normal operations. To illustrate, a small country has no domestic ambulance manufacturers, but imports its vehicles from a larger country in which the manufacturer must comply with a published standard. In most cases, the ambulances imported by the smaller country will end up complying with the larger country's standard, regardless of whether or not this outcome was intended. American and Australian standards were reviewed and considered during the development of the European standard, but were not precisely followed because European needs and priorities were different.

Intent

The standard is intended to gradually transform the existing 'patchwork' of ambulance design and equipment across Europe into a single set of standards. An ambulance from one country would possess sufficiently common characteristics to be immediately recognizable by the residents of another country. Such vehicles would be similar enough in design to be interchangeable, with emergency medical services personnel from one country able to quickly adapt to the use of a vehicle from another country, if required. Above all, such vehicles would be safe for those being transported in them,[4] those working in them, other users of the road, and the general public.

Vehicle standards

Requirements are specified for categories of road ambulances based in increasing order of the level of treatment that can be carried out. The standard includes both vehicle type and also engine type and performance characteristics, including vehicle dimensions, acceleration rate, braking capacity, traction control, fire safety, and heating/cooling.[2]

Interior design standards

The standard contains ergonomic requirements and design specifications for the patient compartment,[5] and also places practical restrictions on the physical lifting of patients in and out of the vehicle, for safety reasons. Other safety factors addressed include lighting, doors & windows, cabinet securing systems, seatbelt and seat anchorage, seat size & position, and restraint of medical equipment, with provisions for static testing, dynamic and impact testing.

Medical devices

This Standard gives general requirements for medical devices carried in road ambulances and used therein and outside hospitals and clinics in situations where the ambient conditions can differ from normal indoor conditions.[6]

Patient and crew Seating

The standard was updated in 2020 to include a reference to patient and crew seating including the requirement for the fitting of a seatbelt alarm to alert the driver visually or acoustically when someone is seated in the patient compartment but not secured by the seatbelt.[7] The Motor Vehicles (Wearing of Seat Belts) Regulations 2015 provide an exemption under specific conditions: 'while the person is providing medical attention or treatment to a patient which due to its nature or the medical situation of the patient cannot be delayed'[8]

Classification of ambulances

Please note that while the classification is standardized in the European Union, the crew and its abilities are not. The same vehicle may be used differently in varying countries. There are also emergency physician based systems in some European states, often with (non-EU regulated) vehicles with medical equipment and therefore lowering the need for the amount of equipment in the ambulance.

- Patient transport ambulances (Types A1 and A2)

Type A1 is without lights and sirens Type A2 with lights and sirens and can function as emergency ambulances. Generally only used for the non-emergency transportation of patients, either between facilities or between a facility and a residence. The emphasis is on transportation; such ambulances have limited treatment or equipment space. Such ambulances may also be used because of cost by smaller communities, particularly if there is no ALS service.

- Emergency ambulances (Type B)

The most commonly seen type of emergency ambulance. This vehicle type permits increased treatment space and also the ability to store significantly larger amounts of medical equipment. Such vehicles will typically respond independently to emergency calls, providing some level of treatment.

- Mobile intensive care unit (Type C)

This type of ambulance is commonly seen in the movement of high acuity (ICU) patients between hospitals. It provides adequate space for not only the medical equipment commonly seen in ambulances, but also to accommodate hospital equipment, such as ventilators, during transport. In some locations, vehicles of this design may be used to provide mobile resuscitation services, either supplemented by an emergency physician response, or with the physician as a part of the crew. In Germany, the vast majority of primary emergency ambulances (Rettungswagen) are required to be Type C ambulance without being dedicated to intensive care transports.[9]

- European Ambulance Classes

-

Type A Ambulance in Poland

-

Type B Ambulance in Switzerland

-

Type C Ambulance in Germany

Ambulance Identity

Active Warning Systems

Emergency Lights

All ambulances will be equipped with flashing blue lights, visible for 360 degrees around the vehicle.[10]

Siren

All vehicles must also be equipped with an audible warning system (siren) which meets specified standards for both sound pattern and volume.

Passive Warning Systems

Vehicle colour

The Standard specifies that all ambulances will be painted yellow, with specific colour standards, as their primary body colour.[11] The colour yellow was chosen primarily because it remains visible to almost all people in all lighting conditions, including the majority of those with colour-blindness. One ambulance service in Europe that does not conform to the standard is the Scottish Ambulance Service, who use white vehicles with ambulance Battenburg markings.

- European Ambulance Visual Identity

-

English ambulance which meets the colour and livery standards

-

Euro Yellow RAL1016 - the colour Standard for Ambulances

-

Swedish Ambulance which meets the colour and livery standards: note the similarities.

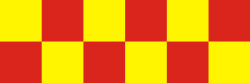

- Visual Identities for Emergency Services

-

Ambulance marking scheme

-

Police marking scheme

-

Fire and Rescue marking scheme

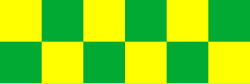

Battenburg Pattern

All ambulances are to be equipped with highly reflective green and yellow 'checkerboard' markings (the English term is 'Battenburg' pattern), of specified proportions, running the entire length of the vehicle. The intent of this measure was to provide specific 'visual identities' for emergency vehicles, by reserving this pattern for ambulances, blue and yellow Battenburg for police cars, and red and yellow Battenburg for fire service vehicles. In addition, all lettering on the vehicle is required to be highly reflective, in order to boost vehicle visibility in all conditions. The colour combination selected was chosen for specific reasons. Under night time conditions, green is among the most visible (exceeded only by blue) of colours, creating high visibility (and safety) for ambulance vehicles. Unfortunately, for many of those who suffer from colour-blindness, neither green nor red is visible, washing out to shades of grey or dark yellow. In fact, almost 99 percent of all colour vision deficiency involves some form of red-green colour blindness, and includes an estimated 7-10 percent of all males, depending on location.[12] However, even for these individuals, the colour yellow is always visible (see diagram). The resulting pattern is both high visibility and eye-catching for the average person, provides improved night time visibility for most, and provides a combination which is identifiable, at least in part, by the majority of the population.

- Colour Vision/Colour Blindness

-

Normal range of colour vision

-

Same image with one form of red/green colour-blindness (1% of males)

-

Most common form of colour-blindness (5% of males)

Star of Life

The blue Star of Life, the international EMS emblem, must be painted on both sides and on top of the vehicle. The mark must be a minimum of 500mm in diameter. This requirement may be waived if the ambulance is part of a national affiliate of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Society. In this case, the Red Cross (or other authorized ICRC emblem) should be used instead. Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. This requirement may also be waived if use of the Star of Life emblem is restricted by local law. The standard also calls for the Star of Life to be used on EMS clothing and apparel. [13]

Word Markings

The vehicle must be marked with the English word "AMBULANCE" and/or the equivalent word in the local language. The text must utilize capital letters, have a letter height of at least 100mm, and the letters must contrast with the background colours.[13]

Application and compliance

As with most European standards, compliance by the member countries of the European Union is purely voluntary, and to be determined at the level of the member country, usually by means of legislation, or by its own standards organization.[14] To illustrate, this standard, which has been accepted by the United Kingdom, is known locally as BS EN 1789:2007, with the 'BS' referring to British Standards. As a result, the adoption of this standard has varied considerably from one country to another. Most countries, for example, have adopted the sections dealing with vehicle design and performance, while only a few (the UK, Ireland, and Sweden at this writing), have fully adopted the colour, warning system, and livery schemes for such vehicles. To further complicate matters, some countries have adopted some portion of the visual identity standards, but not all. In the Netherlands, Belgium, and some parts of Germany, the conversion to the basic identifying colour (yellow) is occurring, but the balance of visual identity provisions are not. In addition, some countries which are not currently members of the European Union, such as Norway are adopting some portions of the standards, primarily because few other good standards exist for this purpose, particularly those that reflect European realities. The rate and degree of compliance with the standard is a conscious choice by individual countries, while in others, compliance is a matter of the priorities for the changing of older, country specific, legislation. As previously stated, compliance with the standard is purely voluntary. There are no untoward financial implications to compliance, since only ambulances purchased after ratification of the standard by each country are required to be compliant. There is no mandatory provision for the retrofitting of existing ambulances.

References

- ^ "Ambulance CEN Approval". Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ a b Committee on European Standards (2007). "Medical Vehicles and their Equipment 1". Cen - en 1789.

- ^ Vogt F (1976). "Equipment: Federal Specification, Ambulance KKK-A-1822" (PDF). Emerg Med Serv. 5 (3): 58, 60–4. PMID 1028572. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-20.

- ^ Shirley PJ, Bion JF (August 2004). "Intra-hospital transport of critically ill patients: minimising risk". Intensive Care Med. 30 (8): 1508–10. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2293-6. PMID 15197442. S2CID 5778449.

- ^ Ferreira J, Hignett S (2005). "Reviewing ambulance design for clinical efficiency and paramedic safety" (PDF). Applied Ergonomics. 36 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2004.07.003. PMID 15627427. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-02.

- ^ Haji-Michael P (August 2005). "Critical care transfers - a danger foreseen is half avoided". Crit Care. 9 (4): 343–4. doi:10.1186/cc3773. PMC 1269476. PMID 16137381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ BS EN 1789:2020 Section 4.4.5

- ^ https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2015/9780111124567 [bare URL]

- ^ "Erlasse - Landesrecht NRW". recht.nrw.de. Ministerium des Innern des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen.

- ^ "RVLR Requirements about using Blue warning beacons".

- ^ Hall, Sarah (2002-03-07). "Ambulances Turn Yellow for Europe (Manchester Guardian article)". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- ^ Sharpe, LT; Stockman A; Jägle H; Nathans J (1999). "Opsin genes, cone photopigments, color vision and color blindness". In Gegenfurtner KR, Sharpe LT (ed.). Color Vision: From Genes to Perception. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00439-8.

- ^ a b "CEN 1789, Annex A Page 39" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-24.

- ^ "European Standards website". Archived from the original on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-10-01.